Museum Victoria's Cabinet of Computing Curiosities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 1-Bit Instrument: the Fundamentals of 1-Bit Synthesis

BLAKE TROISE The 1-Bit Instrument The Fundamentals of 1-Bit Synthesis, Their Implementational Implications, and Instrumental Possibilities ABSTRACT The 1-bit sonic environment (perhaps most famously musically employed on the ZX Spectrum) is defined by extreme limitation. Yet, belying these restrictions, there is a surprisingly expressive instrumental versatility. This article explores the theory behind the primary, idiosyncratically 1-bit techniques available to the composer-programmer, those that are essential when designing “instruments” in 1-bit environments. These techniques include pulse width modulation for timbral manipulation and means of generating virtual polyph- ony in software, such as the pin pulse and pulse interleaving techniques. These methodologies are considered in respect to their compositional implications and instrumental applications. KEYWORDS chiptune, 1-bit, one-bit, ZX Spectrum, pulse pin method, pulse interleaving, timbre, polyphony, history 2020 18 May on guest by http://online.ucpress.edu/jsmg/article-pdf/1/1/44/378624/jsmg_1_1_44.pdf from Downloaded INTRODUCTION As unquestionably evident from the chipmusic scene, it is an understatement to say that there is a lot one can do with simple square waves. One-bit music, generally considered a subdivision of chipmusic,1 takes this one step further: it is the music of a single square wave. The only operation possible in a -bit environment is the variation of amplitude over time, where amplitude is quantized to two states: high or low, on or off. As such, it may seem in- tuitively impossible to achieve traditionally simple musical operations such as polyphony and dynamic control within a -bit environment. Despite these restrictions, the unique tech- niques and auditory tricks of contemporary -bit practice exploit the limits of human per- ception. -

The History of Computer Language Selection

The History of Computer Language Selection Kevin R. Parker College of Business, Idaho State University, Pocatello, Idaho USA [email protected] Bill Davey School of Business Information Technology, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia [email protected] Abstract: This examines the history of computer language choice for both industry use and university programming courses. The study considers events in two developed countries and reveals themes that may be common in the language selection history of other developed nations. History shows a set of recurring problems for those involved in choosing languages. This study shows that those involved in the selection process can be informed by history when making those decisions. Keywords: selection of programming languages, pragmatic approach to selection, pedagogical approach to selection. 1. Introduction The history of computing is often expressed in terms of significant hardware developments. Both the United States and Australia made early contributions in computing. Many trace the dawn of the history of programmable computers to Eckert and Mauchly’s departure from the ENIAC project to start the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation. In Australia, the history of programmable computers starts with CSIRAC, the fourth programmable computer in the world that ran its first test program in 1949. This computer, manufactured by the government science organization (CSIRO), was used into the 1960s as a working machine at the University of Melbourne and still exists as a complete unit at the Museum of Victoria in Melbourne. Australia’s early entry into computing makes a comparison with the United States interesting. These early computers needed programmers, that is, people with the expertise to convert a problem into a mathematical representation directly executable by the computer. -

60 Years of Computing in Victoria(PDF

60 Years of Computing in Victoria 14 JUNE 1956 14 JUNE 2016 WELCOME Justin Zobel HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTING & INFORMATION SYSTEMS, MELBOURNE SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING, THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE We are celebrating the 60th anniversary of computing in Victoria. CSIRAC, Australia’s first computer, resumed operations at the University of Melbourne on 14 June 1956, after being moved from Sydney. CSIRAC is the world’s oldest intact computer, and is now on permanent display at the Melbourne Museum. Many people contributed to this outcome, but in particular Dr Peter Thorne both led the technical work of restoration and made the case for it to be exhibited and conserved - thus giving us and future generations an opportunity to fully appreciate the roots of computing. CSIRAC was originally built in Sydney by the CSIRO before being transferred to The University of Melbourne We welcome this anniversary as an opportunity to highlight the history of computing technology and its impact on our society. TODAY’S SMART MACHINES Not coincidentally, we are also celebrating 60 years of computing education and research at The University of Melbourne. From small OWE MUCH TO AUSTRALIA’S beginnings in the 1950s, the Department of Computing & Information Systems, as it is now known, has become an international FIRST COMPUTER leader in information technology. During the week we look at the remarkable By Justin Zobel SILLIAC, which was launched in September achievements of computing. We have 1956), and operated until 1964. It is now commissioned a series of articles to illustrate Australia’s first computer weighed two a permanent exhibit at Museum Victoria. -

Synthetics: a History of the Electronically Generated Image In

Leonardo_36-3_175-254 5/9/03 9:45 AM Page 187 G C HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE L R O O B S A S L I Synthetics: A History of the N G Electronically Generated Image S in Australia ABSTRACT This paper takes a brief look at the early years of computer- graphic and video- synthesizer–driven image Stephen Jones production in Australia. It begins with the first (known) Australian data visualization, in 1957, and proceeds through the composit- ing of computer graphics and video effects in the music videos of the late 1980s. The his article surveys the development of com- netic Serendipity exhibition at the author surveys the types of T work produced by workers on puter art and video synthesis in Australia from its earliest man- Institute of Contemporary Art in ifestation through to the late 1980s. I focus on the artists and London [6]. He returned to Aus- the computer graphics and video synthesis systems of the the technologies they used, with pointers to cultural/aesthetic tralia with a collection of CG slides early period and draws out issues. The technologies derive from computing—both ana- from artists and programmers and some indications of the influ- log, which evolved into audio and video synthesizers, and dig- began to proselytize computer art ences and interactions among ital, which was domesticated over this period. to students and computing profes- artists and engineers and the technical systems they had sionals there [7]. Artists and com- available, which guided the puters did not mix in those days. evolution of the field for artistic DATA VISUALIZATION The process of writing and running production. -

A Large Routine

A large routine Freek Wiedijk It is not widely known, but already in June 1949∗ Alan Turing had the main concepts that still are the basis for the best approach to program verification known today (and for which Tony Hoare developed a logic in 1969). In his three page paper Checking a large routine, Turing describes how to verify the correctness of a program that calculates the factorial function by repeated additions. He both shows how to use invariants to establish the correctness of this program, as well as how to use a variant to establish termination. In the paper the program is only presented as a flow chart. A modern C rendering is: int fac (int n) { int s, r, u, v; for (u = r = 1; v = u, r < n; r++) for (s = 1; u += v, s++ < r; ) ; return u; } Turing's paper seems not to have been properly appreciated at the time. At the EDSAC conference where Turing presented the paper, Douglas Hartree criticized that the correctness proof sketched by Turing should not be called inductive. From a modern point of view this is clearly absurd. Marc Schoolderman first told me about this paper (and in his master's thesis used the modern Why3 tool of Jean-Christophe Filli^atreto make Turing's paper fully precise; he also wrote the above C version of Turing's program). He then challenged me to speculate what specific computer Turing had in mind in the paper, and what the actual program for that computer might have been. My answer is that the `EPICAC'y of this paper probably was the Manchester Mark 1. -

Creative Quantum Computing: Inverse FFT Sound Synthesis, Adaptive Sequencing and Musical Composition

Creative Quantum Computing: Inverse FFT Sound Synthesis, Adaptive Sequencing and Musical Composition Eduardo R. Miranda To appear as a chapter in the book: Alternative Computing, edited by Andrew Adamatzky. World Scientific, 2021. Disclaimer: This is the authors’ own edited version of the manuscript. It is a prepublication draft, where some minor errors and inconsistencies might be present. And it is likely to undergo further peer review. This version is made available here in agreement with the book’s editor. Creative Quantum Computing: Inverse FFT Sound Synthesis, Adaptive Sequencing and Musical Composition Eduardo R. Miranda Interdisciplinary Centre for Computer Music Research (ICCMR) University of Plymouth Ada Lovelace House, 24 Endsleigh Place Plymouth PL4 6DN United Kingdom Abstract: Quantum computing is emerging as an alternative computing technology, which is built on the principles of subatomic physics. In spite of continuing progress in developing increasingly more sophisticated hardware and software, access to quantum computing still requires specialist expertise that is largely confined to research laboratories. Moreover, the target applications for these developments remain primarily scientific. This chapter introduces research aimed at improving this scenario. Our research is aimed at extending the range of applications of quantum computing towards the arts and creative applications, music being our point of departure. This chapter reports on initial outcomes, whereby quantum information processing controls an inverse Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) sound synthesizer and an adaptive musical sequencer. A composition called Zeno is presented to illustrate a practical real-world application. 1 Introduction Quantum computing is emerging as a powerful alternative computing technology, which is built on the principles of subatomic physics. -

Early Computer Music Experiments in Australia and England

Early Computer Music Experiments in Australia and England PAUL DOORNBUSCH Australian College of the Arts, 55 Brady Street, South Melbourne, VIC 3205, Australia Email: [email protected] This article documents the early experiments in both Australia had been developed, such as the ‘linear equations and England to make a computer play music. The experiments machine’, the ‘differential analyser’ and the ‘multi- in England with the Ferranti Mark 1 and the Pilot ACE register accounting machine’ (Hemstead and (practically undocumented at the writing of this article) and Worthington 2005: 110; Hally 2006: 11–13). However, fi those in Australia with CSIRAC (Council for Scienti c and the calculating machines still required significant Industrial Research Automatic Computer) are the oldest human intervention, so there was a desire to build an known examples of using a computer to play music. Significantly, they occurred some six years before the automatic calculator with some sort of system to store experiments at Bell Labs in the USA. Furthermore, the the data and the instructions for what to do with computers played music in real time. These developments were the data. important, and despite not directly leading to later highly There were some major technological advances at significant developments such as those at Bell Labs under the the time that allowed the realisation of an automatic direction of Max Mathews, these forward-thinking develop- calculator with memory. One such advance was the ments in England and Australia show a history of computing use of thermionic valves (vacuum tubes), as switching machines being used musically since the earliest development devices. -

CMJ 42-3 28-46.Pdf (5.256Mb)

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of Society and Culture Composing with Biomemristors: Is Biocomputing the New Technology of Computer Music? Miranda, ER http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/12704 10.1162/comj_a_00469 Computer Music Journal Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press (MIT Press) All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Miranda, Braund and Venkatesh 1 This is the authors’ own edited version of the accepted version manuscript. It is a prepublication version and some errors and inconsistencies may be present. The full published version of this work appeared in Computer Music Journal 42(3):28-46 after amendments and revisions in liaison with the editorial and publication team. This version is made available here in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Computer Music Journal Miranda, Braund and Venkatesh 2 Music and Biocomputing: Is Music Biotech the New Computer Music? Eduardo Reck Miranda*, Edward Braund* and Satvik Venkatesh* *Interdisciplinary Centre for Computer Music Research (ICCMR) Plymouth University The House Plymouth PL4 8AA United Kingdom {eduardo.miranda, edward.braund}@plymouth.ac.uk [email protected] Abstract: Our research concerns the development of biocomputers using electronic components grown out of biological material. This paper reports the development of an unprecedented biological memristor and an approach to using such a biomemristors to build interactive generative music systems. -

Paper Submission Template

European Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology Vol.3, No.1, pp. 15-42, March 2015 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) CATEGORIES AND GENERATIONS OF COMPUTERS Ionescu Andreea The Hyperion University from Bucharest ABSTRACT: This scientific article speaks about generations of computers, PC history, saving data, Von Neumann architecture, input/output peripherals, software instructions, programs, mainframe, minicomputers, microcomputers, supercomputers, libraries and operating systems, computer networks and Internet, introduction to the world of computers, evolution of computer systems, from the literature specialized in computer science. Computers are divided into: mechanical computers-water and gas meters, electromechanical computers-electricity meters, electronic computers (I generation of computers, II generation of computers, III generation of computers, IV generation of computers), optical computers and biological computers. After the highest prevalence, electronic computers are divided into: analogue- electronic computers, digital electronic-computers and hybrid electronic computers. KEYWORDS: Mainframe, Minicomputers, Microcomputers, Supercomputers, Computers, Operating Systems; INTRODUCTION This scientific article speaks about: the electronic computer, the computer science, the Information Technology, PC-History, personal computers, Von Neumann Architecture(an electronic computer with four major modeules: Arithmetic-Logic Unit(ALU), Control Unit(CU), Central -

DATAFLOW COMPUTERS: THEIR HISTORY and to Improve the Hybrid Systems

D DATAFLOW COMPUTERS: THEIR HISTORY AND to improve the hybrid systems. The next section outlines FUTURE research issues in handling data structures, program allo- cation, and application of cache memories. Several proposed INTRODUCTION AND MOTIVATION methodologies will be presented and analyzed. Finally, the last section concludes the article. As we approach the technological limitations, concurrency will become the major path to increase the computational DATAFLOW PRINCIPLES speed of computers. Conventional parallel/concurrent sys- tems are based mainly on the control-flow paradigm, where The dataflow model of computation deviates from the con- a primitive set of operations are performed sequentially on ventional control-flow method in two fundamental ways: data stored in some storage device. Concurrency in con- asynchrony and functionality. Dataflow instructions are ventional systems is based on instruction level parallelism enabled for execution when all the required operands (ILP), data level parallelism (DLP), and/or thread level are available, in contrast to control-flow instructions, which parallelism (TLP). These parallelisms are achieved using are executed sequentially under the control of a program techniques such as deep pipelining, out-of-order execution, counter. In dataflow, any two enabled instructions do not speculative execution, and multithreaded execution of interfere with each other and thus can be executed in any instructions with considerable hardware and software order, or even concurrently. In a dataflow environment, resources. conventional concepts such as ‘‘variables’’ and ‘‘memory The dataflow model of computation offers an attractive updating’’ are nonexistent. Instead, objects (data struc- alternative to control flow in extracting parallelism from tures or scalar values) are consumed by an actor (instruc- programs. -

Connections in the History of Australian Computing

Connections in the History of Australian Computing John Deane Australian Computer Museum Society, PO Box S-5, Homebush South, NSW 2140, Australia [email protected] Abstract. This paper gives an overview of early Australian computing mile- stones up to about 1970 and demonstrates a mesh of influences. Wartime radar, initially from Britain, provided basic experience for many computing engineers. UK academic Douglas Hartree seems to have known all the early developers and he played a significant part in the first Australian computing conference. John von Neumann’s two pioneering designs directly influenced four of the first Australian machines, and published US designs were taken up enthusiastically. Influences passed from Australia to the world too. Charles Hamblin’s Reverse Polish Notation influenced English Electric’s KDF9, and succeeding stack ar- chitecture computers. Chris Wallace contributed to English Electric, and Murray Allen worked at Control Data. Of course the Australians influenced each other: Myers, Pearcey, Ovenstone, Bennett and Allen organized confer- ences, interacted on projects, and created the Australian Computer Societies. Even horse racing played a role. Keywords: Australia, computing, Myers, Pearcey, Ovenstone, Bennett, Allen, Wong, Hamblin, Hartree, Wilkes, CSIRO, CSIRAC, SILLIAC, UTECOM, WREDAC, SNOCOM, CIRRUS, ATROPOS, ARCTURUS. 1 Introduction The history of computing in Australia can be seen as a nearly continuous series of personal connections, both within the country and internationally. The following sec- tions highlight some of the influences on the early Australian projects. 2 George Julius’ Automatic Totalisator There have been calculating aids in Australia for as long as there have been people here, but one of the first mechanical aids associated with Australia was developed by a mechanical engineer, George Julius. -

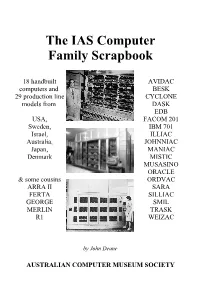

The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook

The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook 18 handbuilt AVIDAC computers and BESK 29 production line CYCLONE models from DASK EDB USA, FACOM 201 Sweden, IBM 701 Israel, ILLIAC Australia, JOHNNIAC Japan, MANIAC Denmark MISTIC MUSASINO ORACLE & some cousins ORDVAC ARRA II SARA FERTA SILLIAC GEORGE SMIL MERLIN TRASK R1 WEIZAC by John Deane AUSTRALIAN COMPUTER MUSEUM SOCIETY The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook by John Deane Front cover: John von Neumann and the IAS Computer (Photo by Alan Richards, courtesy of the Archives of the Institute for Advanced Study), Rand's JOHNNIAC (Rand Corp photo), University of Sydney's SILLIAC (photo courtesy of the University of Sydney Science Foundation for Physics). Back cover: Lawrence Von Tersch surrounded by parts of Michigan State University's MISTIC (photo courtesy of Michigan State University). The “IAS Family” is more formally known as Princeton Class machines (the Institute for Advanced Study is at Princeton, NJ, USA), and they were referred to as JONIACs by Klara von Neumann in her forward to her husband's book The Computer and the Brain. Photograph copyright generally belongs to the institution that built the machine. Text © 2003 John Deane [email protected] Published by the Australian Computer Museum Society Inc PO Box 847, Pennant Hills NSW 2120, Australia Acknowledgments My thanks to Simon Lavington & J.A.N. Lee for your encouragement. A great many people responded to my questions about their machines while I was working on a history of SILLIAC. I have been sent manuals, newsletters, web references, photos,