Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018

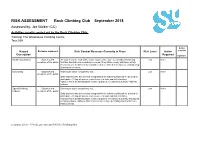

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018 Assessed by: Joe Walker (CC) Activities usually carried out by the Rock Climbing Club: Training: The Warehouse Climbing Centre Tour: N/A Action Hazard Persons exposed Risk Control Measures Currently in Place Risk Level Action complete Description Required signature Bouldering (Indoor) Students and All students of the club will be made aware of the safe use of indoor bouldering Low None members of the public facilities and will be immediately removed if they fail to comply with these safety measures or a member of the committee believe that their actions are endangering themselves or others. Auto-Belay Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay climbing indoors. Speed Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay and speed climbing indoors, ability to differentiate between speed climbing and normal auto belay systems. y:\sports\2018 - 19\risk assessments\UGSU Climbing RA Top Rope Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Med None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate in belaying - Fitting a harness, tying of a threaded figure of 8 knot, correct use of a belay device, correct belaying technique, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to top rope climbing indoors. -

Avocation Questionnaire

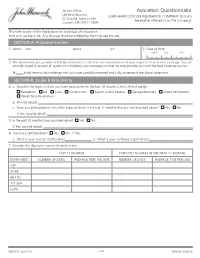

Service Office: Avocation Questionnaire Life New Business JOHN HANCOCK LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY (U.S.A.) 30 Dan Rd, Suite 55765 (hereinafter referred to as The Company) Canton, MA 02021-2809 This form is part of the Application for Individual Life Insurance. Print and use black ink. Any changes must be initialed by the Proposed Insured. SECTION A: Proposed Insured 1. Name FIRST MIDDLE LAST 2. Date of Birth MONTH DAY YEAR 3. The information you provide in this Questionnaire is critical to our consideration of your request for insurance coverage. You are strongly urged to answer all questions completely and accurately so that we may provide you with the best coverage we can. X Initial here to acknowledge that you have carefully reviewed and fully understand the above statement. SECTION B: Scuba & Skin Diving 4. a. Describe the types of dives you have participated in the last 12 months (check all that apply): Recreation Ice Cave Construction Search and/or Rescue Salvage/Recovery Wreck Penetration Wreck Non-Penetration b. Provide details c. Have you participated in any other types of dives in the last 12 months that are not described above? Yes No If Yes, provide details 5. In the past 12 months, have you dived alone? Yes No If Yes, provide details 6. Are you a certified diver? Yes No If Yes, a. What is your level of certification? b. What is your certifying organization? 7. Describe the dives you have performed in the: LAST 12 MONTHS EXPECTED TO MAKE IN THE NEXT 12 MONTHS DEPTH (FEET) NUMBER OF DIVES AVERAGE TIME PER DIVE NUMBER OF DIVES AVERAGE TIME PER DIVE <30 30-65 66-130 131-200 >200 NB5010FL (03/2016) 1 of 4 VERSION (03/2016) SECTION C: Automobile, Motorcycle and Power Boat Racing 8. -

A Climber's Guide to Townsville and Magnetic Island

Contents: Mt Stuart Castle Hill Minor Crags: West End Quarry Lazy Afternoon Wall University Wall Kissing Point Magnetic Island Front Cover: Curlew (23), Rocky Bay, Magnetic Island. Inside Front: Mt Stuart at dawn. Inside Back: Castle Hill at dawn. Back Cover: Physical Meditation(25), The Pinnacle, Mt Stuart. All photos by me unless acknowledged. Thanks to: everyone I’ve climbed with, especially Steve Baskerville and Jason Shaw for going to many of the minor crags with me; Scott Johnson for sending me a copy of his guide and other information; Lee Skidmore, Mark Gommers and Anthony Timms for going through drafts; Lee for letting me use slides and information from his Website; Andrew and Deb Thorogood for being very amenable employers and for letting me use their computer; Aussie Photographics whose cheap developing I recommend; Simon Thorogood for scanning the slides; the Army for letting us climb at Mt Stuart; the Rocks for being there and Tash for buying a computer and being lovely. Dedicated to Jason Shaw. Contact me at [email protected]. 1 Disclaimer Many of the climbs in this book have had few ascents. Rockclimbing is hazardous. The author accepts no responsibility for any inaccurate or incomplete information, nor for any controversial grading of climbs or dependance on fixed protection, some of which may be unreliable. This guide also assumes that users have a high level of ability, have received training from a skilled rockclimbing instructor, will use appropriate equipment properly and have care for personal safety. Also it should be obvious that large amounts of this publication are my opinion. -

POISTNÁ ZMLUVA PRE SKUPINOVÉ ÚRAZOVÉ POISTENIE Číslo

POISTNÁ ZMLUVA PRE SKUPINOVÉ ÚRAZOVÉ POISTENIE číslo 2-370-300493 Zmluvné strany: Colonnade Insurance S.A. so sídlom Rue Eugène Ruppert 20, L-2453 Luxemburg, Luxembursko zapísaná v Obchodnom registri Luxemburg pod č. B 61605 konajúca prostredníctvom Colonnade Insurance S.A., pobočka poisťovne z iného členského štátu Štúrova 27, 042 80 Košice, Slovenská republika IČO: 50 013 602 zapísaná v Obchodnom registri Okresného súdu Košice I, oddiel Po, vložka číslo 591/V DIČ: 4120026471 IČ DPH: SK4120026471 v zastúpení: Ing. Marian Bátovský, senior underwriter konajúci na základe poverenia Ing. Cyntia Benešová, senior underwriter konajúci na základe poverenia Bankové spojenie: Citibank Europe plc, pobočka zahraničnej banky SWIFT: CITISKBA IBAN: SK16 8130 0000 0011 0210 0306 (ďalej len „poisťovňa“ ) a Gymnázium Jána Adama Raymana Mudroňova 20, 080 01 Prešov, Slovenská republika IČO: 00 161 101 DIČ: IČ DPH: neplatca DPH v zastúpení: Mgr. Viera Kundľová, riaditeľka Bankové spojenie: Štátna pokladnica SWIFT: SPSRSKBA IBAN: SK67 8180 0000 0070 00515647 (ďalej len „poistník“ ) Sprostredkovateľ poistenia: JUST s.r.o., člen skupiny RESPECT SLOVAKIA, Weberova 2, 080 01 Prešov, IČO: 36443549 uzatvárajú v zmysle § 788 a nasl. Občianskeho zákonníka túto poistnú zmluvu pre skupinové úrazové poistenie žiakov a študentov škôl Skupinové úrazové poistenie – špecifikácia Doba trvania poistenia: Doba určitá. Začiatok poistenia: 1. február 2018 Koniec poistenia: 6. októbra 2018 (24:00 hod) Poistné: Celková výška jednorazového poistného je 1 139,78 EUR a vyplýva z Prílohy č. 1. Splatnosť poistného: Poistné je splatné 1. februára 2018. Spôsob úhrady poistného: Poistník uhrádza poistné na účet poisťovne s IBAN SK1681300000001102100306, SWIFT: CITISKBA , variabilný symbol je 2370300493, konštantný symbol 3558. -

Seznam Sportů Bez Navýšení Základních Sazeb

Seznam sportů bez navýšení základních sazeb aerials lyžování po vyznačených trasách aerobic metaná aerotrim moderní gymnastika airsoft monoski americký fotbal mountainboarding na vyznačených trasách, při soutěžích aquaaerobic nohejbal atletika včetně skoku o tyči a pěti, sedmi a desetiboje orientační běh badminton paintball baseball parasailing basketbal petanque běh na lyžích po vyznačených trasách plavání biatlon plážový volejbal bikros podvodní ragby boby na vyznačených trasách pozemní hokej boccia psí spřežení bowling radiový orientační běh bridge ragby bruslení na ledě rope jumping bublík rybolov ze člunu buggykiting sálová kopaná bumerang saně na vyznačených trasách bungee running showdown bungee trampolin silniční běh curling skateboarding cyklistika skiatlon cyklokros skiboby dětské tábory bez sportovního zaměření a se sportovním zaměřením skikros dragboat - dračí lodě, pádlování skoky na trampolíně duatlon slalom na lyžích fitness a bodybulding sledge hokej florbal snowboarding po vyznačených trasách fly fox snowkiting footbag snowtrampoline fotbal snowtubbing - na vyznačených trasách frisbee softbal goalball spinning golf sportovní gymnastika hasičský sport + cvičení záchranných sborů sportovní rybaření házená sportovní střelba (střelba na terč s použitím střelné zbraně) historiský šerm (bojový) squash hokejbal stolní fotbal horské kolo (ne sjezd) stolní hokej cheerleaders - roztleskávačky stolní společenské hry in-line bruslení stolní tenis jezdecké sporty synchronizované plavání jízda na "U" rampě (in-line,skateboard, lyže) -

Climbing the City. Inhabiting Verticality Outside of Comfort Bubbles

Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability ISSN: 1754-9175 (Print) 1754-9183 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjou20 Climbing the city. Inhabiting verticality outside of comfort bubbles Andrea Mubi Brighenti & Andrea Pavoni To cite this article: Andrea Mubi Brighenti & Andrea Pavoni (2017): Climbing the city. Inhabiting verticality outside of comfort bubbles, Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, DOI: 10.1080/17549175.2017.1360377 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2017.1360377 Published online: 05 Aug 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjou20 Download by: [79.30.197.227] Date: 05 August 2017, At: 02:22 JOURNAL OF URBANISM, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2017.1360377 Climbing the city. Inhabiting verticality outside of comfort bubbles Andrea Mubi Brighentia and Andrea Pavonib aDepartment of Sociology, University of Trento, Trento, Italy; bDINAMIA’CET (Centre for Socioeconomic and Territorial Studies), University Institute of Lisbon (ISCTE-IUL), Lisbon, Portugal ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Over the last couple of decades, urban sports have been studied – as Urban theory; urban well as, in many cases, celebrated – as critical forms of using urban climbing; urban space. Urban climbing, a practice also known as “street bouldering,” environment; inhabiting; “buildering,” “structuring,” and “stegophilia,” has been much explored bodily urban practice; object/environment in this vein. While we acknowledge the importance of bringing to light relations; compositional the political and playful dimensions of the urban spatial experience, techniques in this piece we would like to focus on a slightly different question. -

BAF Brochure 2013 WEB.Pdf

WHAT IS BAF? TICKET PRICES Buxton Adventure Festival is the latest adventure organised by Heason Events - MAIN THEATRE SESSIONS: speakers, films & events for adventurous spirits and minds. Adult: £10.00 for 1 session We launched the festival last year after the phenomenal growth of the annual Multi-buy Saver: 3 sessions for £25 Sheffield Adventure Film Festival and the popularity of our lecture nights at Buxton Full-time Students & Under 16s: £5 for 1 session Opera House given by the likes of the world’s greatest living explorer, Sir Ranulph Multi-buy Saver: 3 sessions for £12.50 Fiennes, and Britain’s top climbing talent, Leo Houlding. Family Saver Session Ticket (2 adults and 2 under 16s): £20 We wanted to combine the excitement of live lectures with the thrill of big screen cinema. Over two days, visitors can choose from an inspirational series of ten Note - Each ticket is for a session and includes the different two hour talk+film sessions with tales of intrepid expeditions, challenges speaker AND following film programme and races brought to life by world-class speakers paired with epic films of climbs, runs and rides. ADVENTURE BITES FILM LOOP We’re proud to say that 100% of last year’s audience said they loved the format and (THE STUDIO THEATRE): would recommend it to a friend. £4 for adults and £2 for children and students This year we think the line-up is even stronger with inspirational talks and some of the autumn’s most eagerly anticipated new releases. We’re also introducing ‘Adventure Bites’ - an hour-long, family friendly loop of 10 action-packed, short adventure films with individual wifi headphones in the TABLE OF CONTENTS adjacent Studio Theatre so you can drop in at any point during the weekend. -

The History and Culture of Climbing in the US

SYLLABUS FOR FRESHMAN SEMINAR 124: The History and Culture of Climbing in the US Professor John Gager Spring Semester, 2009 Question to Sir George Mallory: “Why do you want to climb Mt. Everest?” His answer: Because it is there.” Feb. 4: Introduction What is climbing? Where did it come from? Terms, gear and styles in rock climbing: free climbing (leading, trad and sport climbing), top-roping, competitions, bouldering, buildering, soloing/free soloing, rope soloing, aid climbing; ice climbing; mountaineering • Wikipedia article ‘rock climbing - styles’ --- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock_climbing • DVD • *R. Bates, Mystery, Beauty and Danger, pp. 1-22 • *E. Whymper, Scrambles amongst the Alps, (various illustrations) pp. 85,118, 172, 236, 290 • *Lito Tejada-Flores, “Games Climbers Play,” in The Games Climbers Play, ed. Ken Wilson (1978; at Dartmouth) 19-27 Feb. 11: The Beginnings in the Northeast • **Waterman, 1-52, 117-47 • http://www128.pair.com/r3d4k7/Bouldering_History1.0.html Feb. 18: The Beginnings in the West – Yosemite: • **S. Roper, CAMP 4 • Big Walls by Chris McNamara (Yosemite Big Walls) - http://www.supertopo.com/freetopos.html#snakedike and follow the path to Snake Dike (ignore “More info” and “Purchase”) 1 Feb. 25: American Mountaineering – Attempts on K2 • *Bates et al. in Jim Curran, K2. The Story … ch. 6, 8, 11; • “Into the Void” (film) March 4: Can women climb? Guest = Majka Burhardt, ‘99 • **Lynn Hill, Climbing Free; • **Waterman, pp. 282-90 • 3 Majka Burhardt pieces (handouts) • *Sherry Ortner, LIFE AND DEATH…, pp. 217-31 March 11: Vulgarians, Appies and Princetonians • **Waterman, chs. 13, 14, 15; • **D. Roberts, “Boulder and the Gunks” in Moments of Doubt , pp. -

AXA-Mountaineering & Rock Climbing Questionnaire

Mountaineering / Rock Climbing Questionnaire To be completed by the Applicant Name, First name : ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Application no. : ______________________________________________________________ Dated: _________________________________________ This questionnaire will form part of the application. Provide as much detail as possible. If you are not sure whether any information is relevant, please disclose it anyway. 1. What types of mountaineering I climbing activities do you pursue? Check all that apply and where requested, please provide further details. a) Hiking / Walking / Scrambling Bouldering Artificial or Indoor climbing Trekking Via ferrata Sport climbing Snowshoeing Skitours/Snowboardtours Since when? _______________ Average no. of days per year? _______________ Alpine climbing Since when? _______________ Average no. of days per year? _______________ Ice climbing Since when? _______________ Average no. of days per year? _______________ Big wall climbing Since when? _______________ Average no. of days per year? _______________ Traditional mountaineering Since when? _______________ Average no. of days per year? _______________ Buildering Since when? _______________ Average no. of days per year? _______________ b) Expeditions Other mountaineering / climbing activities Please specify _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2. Do you ever climb alone or -

From the Reference Desk Thomas Gilson College of Charleston, [email protected]

Against the Grain Volume 19 | Issue 3 Article 23 June 2007 From the Reference Desk Thomas Gilson College of Charleston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/atg Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Gilson, Thomas (2007) "From the Reference Desk," Against the Grain: Vol. 19: Iss. 3, Article 23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.5380 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. From the Reference Desk by Tom Gilson (Head, Reference Services, Addlestone Library, College of Charleston, 66 George Street, Charleston, SC 29401; Phone: 843-953-8014; Fax: 843-953-8019) <[email protected]> Anyone who watches ESPN and its various part of a well rounded reference collection. pedias and this is a timely addition. Medieval spin-off channels is aware that extreme sports Given the popular interest in the topic, they Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia (2006, are emerging from the margins to gain main- may also want to add it to their circulating 0415966914, $350) is a two-volume set that stream attention. A new reference, the Berk- collections. Larger public libraries may also aims to “bridge the gap between what we shire Encyclopedia of Extreme Sports (2007, be interested for similar reasons. perceive Islam and Islamic civilization to be 0-9770159-5-5, $125) takes a serious look at about and what it really is.” While the religious this growing component of the international aspects of Medieval Islam are treated, the em- sports scene and attempts an “in-depth dissec- The Encyclopedia of Activism and Social phasis is on the broader culture and civilization tion of this new and emerging phenomenon.” Justice (2007, 141291812X, $495) is a new of the Muslim world. -

Supertopo Rock Climbing Discussio

Who the hell are you people?... Supertopoan Pictures... :: SuperTopo Rock Climbing Discussio... http://www.supertopo.com/climbing/thread.html?topic_id=345899&tn=0&mr=0 Home Climbing Areas Climbing Routes Guidebooks Free Topos Photos Forum Home >> Forum >> Message Sunday, February 10, 2008 Check 'em out! SuperTopo Climber’s Forum SuperTopo Guidebooks Welcome Guest! Return to Forum List Post a Reply Forum Help Sign In Messages 1 - 1250 of total 1250 in this topic Who the hell are you people?... Supertopoan Pictures... Mar 22, 2007, 11:40am PST Who's brave enough to post a recent picture of themselves? Not a hero shot of you on some sick route from 60 feet away either. Post something that would allow people to recognize Topic Author: you at the crag/sushi bar. (no crotch shots Ouch!) piquaclimber I'll even go first... (this is from my bachelor party... we rented a bus to cart our drunk asses around) Try a free sample topo! Trad climber From: Durango Brad Brandewie (a.k.a. piquaclimber) Get the climbing news! Enter your email below: Subscribe Search SuperTopo Search Free downloads: Snake Dike, 5.7R Fairview Dome, 5.9 Astroman, 5.11c Muir Wall, El Cap Canyonlands, 5.11 Lover's Leap, 5.7 Muir Wall, El Cap High Sierra, 5.10 Red Rocks, 5.10a Tahoe Bouldering Denali, Alaska Bay Area Bouldering Yosemite Bouldering Features: Forum Route beta Topo store Yosemite About us Contact Koren, my better half, on our big day... How To's: Get to Yosemite Stay in Yosemite Resources: Our favorite links ASCA American Alpine Club Access Fund How can we improve SuperTopo? Let us know! Ads by Google Be A Professional Slacker Re: Who the hell are you people?.. -

List of Activities and Sports

LIST OF ACTIVITIES AND SPORTS Chráníme to nejcennější SPORT 1/20 valid as of 1 January 2020 WITH THE NEED FOR TAKING OUT SUPPLEMENTARY INSURANCE WITHOUT THE NEED FOR TAKING OUT SUPPLEMENTARY INSURANCE UNINSURABLE HAZARDOUS EXTREME aerobics, kickbox aerobic, aqua majorettes acrobatic rock and roll aerials alpinism aerobic, yoga, fitness exercising Ice stock sport american football acrobatics in general (e.g. artistes) base jumping aerotrim minigolf BMX acrobatic water skiing buildering agility sport modelling martial arts to the extent of capoeira, acrobatic winter skiing cave diving airsoft modern gymnastics jiu-jitsu, judo, karate downhill skiing canoe slalom (grade VI) animation programmes foot tennis bouldering (on artificial rock walls) bobsled racing dragster racing athletics orienteering and cross-country box lacrosse martial arts to the extent of aikido, extreme skiing badminton running canicross in difficult terrain allkampf-jitsu, kung-fu, taekwondo, extreme power sports (pulling ballet paddleboard competitive cycling (road and track) sumo, box, kick boxing, thai boxing of heavy weights, vehicles by a baseball paintball cyclo-cross, bike trial bouldering (not on artificial rock walls) cable, etc.) basketball petanque canoe slalom (grades III-IV) bungee jumping freeride (whatever) cross-country skiing (along marked swimming horse racing canyoning heliskiing trails) beach and water-based recreational quidditch canoe slalom (grade V) high jumping (cliffdiving) running - jogging,