Stanford Alpine Club Exhibit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

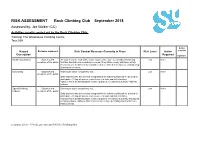

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018 Assessed by: Joe Walker (CC) Activities usually carried out by the Rock Climbing Club: Training: The Warehouse Climbing Centre Tour: N/A Action Hazard Persons exposed Risk Control Measures Currently in Place Risk Level Action complete Description Required signature Bouldering (Indoor) Students and All students of the club will be made aware of the safe use of indoor bouldering Low None members of the public facilities and will be immediately removed if they fail to comply with these safety measures or a member of the committee believe that their actions are endangering themselves or others. Auto-Belay Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay climbing indoors. Speed Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay and speed climbing indoors, ability to differentiate between speed climbing and normal auto belay systems. y:\sports\2018 - 19\risk assessments\UGSU Climbing RA Top Rope Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Med None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate in belaying - Fitting a harness, tying of a threaded figure of 8 knot, correct use of a belay device, correct belaying technique, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to top rope climbing indoors. -

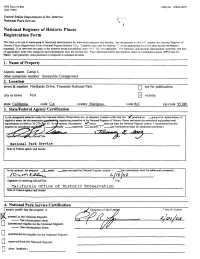

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior » , • National Park Service V National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts Sec instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" lor 'not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and area of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10- 900A). Use typewriter, word processor or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Camp 4 other name/site number Sunnyside Campground__________________________________________ 2. Location_______________________________________________________ street & number Northside Drive, Yosemite National Park |~1 not for publication city or town N/A [_xj vicinity state California code CA county Mariposa code 043 zip code 95389 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Itjiomination _irquest for determination of eligibility meets the documentationsJand»ds-iJar -

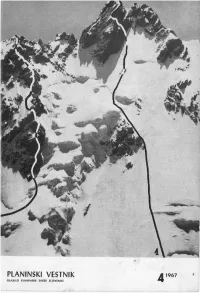

PV 1967 04.Pdf

poštnina plačana v gotovini VSEBINA: RAZMIŠLJANJA OB NAŠIH ODPRAVAH V KAVKAZ Ing. Pavle Šegula 145 KAVKAZ - MOST MED ALPAMI IN HIMALAJO EMO Janez Krušic 149 SLOVENSKO REBRO V SEVERNI STENI GESTOLE Celje Janez Krušic 157 SLOVENSKI STEBER V ULLU-AUSU Ing. Drago Zagorc 160 TIMOFEJEVA SMER V MIŽIRGIJU EMAJLIRNICA Janez Golob 161 METALNA INDUSTRIJA KAKO SE JE CVET SLOVENSKIH ALPINISTOV PRIVAJAL NA VIŠINO 5145 METROV ORODJARNA Boris Krivic 164 NJEGOV ZADNJI VZPON A. Kopinšek 168 IZDELUJE IN DOBAVLJA: K DISKUSIJI O NEKATERIH KRAŠKIH OBLIKAH VISO- KOGORSKEGA KRASA — frite z dodatki za izdelavo emajlov Dušan Novak 169 — emajlirano, pocinkano in alu posodo, sanitarno SEDEM DESETLETIJ PLANINSKEGA VESTNIKA in gospodinjsko opremo ter kovinsko embalažo (1895-1965) — toplotne naprave: radiatorje in kotle za cen- Evgen Lovšin 174 tralno in etažno ogrevanje GOZD JE NAŠ DOM 180 — odpreske in kolesa za motorna vozila ter od- DRUŠTVENE NOVICE 183 preske za rudarstvo ALPINISTIČNE NOVICE 184 — vse vrste orodij zo serijsko proizvodnjo: rezilna, IZ PLANINSKE LITERATURE 187 izsekovalna, vlečna, kombinirana in upogibna RAZGLED PO SVETU 188 orodja za predelavo pločevine, orodja za tlačni ANICA KUK liv in za proizvodnjo iz plastičnih mas, stekla Stanislav Gilič 191 in keramike NASLOVNA STRAN: — emajlira, pocinkuje in predeluje pločevine SEVERNO OSTENJE ULLU-AUS (4789 m) 1 - DIREKTNA SMER V SEVERNI STENI Tel.: 39-21 - Telegram: EMO-Celje - Telex: 0335-12 2 - SLOVENSKI STEBER - PRVENSTVENA SMER SEDEŽ: LJUBLJANA - VEVČE USTANOVLJENE LETA 1842 IZDELUJEJO SULFITNO CELULOZO I. a za vse vrste papirja PINOTAN - strojilni ekstrat BREZLESNI PAPIR za grafično in predelovalno in- dustrijo: za reprezentativne izdaje, umetniške slike, propagandne in turistične prospekte, za pisemski papir in kuverte najboljše kvalitete, za razne protokole, matične knjige, obrazce, -Planinski Vestnik« je glasilo Planinske zveze Slovenije / šolske zvezke in podobno Izdaja ga PZS - urejuje ga uredniški odbor. -

Pinnacle Club Jubilee Journal 1921-1971

© Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved PINNACLE CLUB JUBILEE JOURNAL 1921-1971 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB JOURNAL Fiftieth Anniversary Edition Published Edited by Gill Fuller No. 14 1969——70 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE 1971 1921-1971 President: MRS. JANET ROGERS 8 The Penlee, Windsor Terrace, Penarth, Glamorganshire Vice-President: Miss MARGARET DARVALL The Coach House, Lyndhurst Terrace, London N.W.3 (Tel. 01-794 7133) Hon. Secretary: MRS. PAT DALEY 73 Selby Lane, Keyworth, Nottingham (Tel. 060-77 3334) Hon. Treasurer: MRS. ADA SHAW 25 Crowther Close, Beverley, Yorkshire (Tel. 0482 883826) Hon. Meets Secretary: Miss ANGELA FALLER 101 Woodland Hill, Whitkirk, Leeds 15 (Tel. 0532 648270) Hon Librarian: Miss BARBARA SPARK Highfield, College Road, Bangor, North Wales (Tel. Bangor 3330) Hon. Editor: Mrs. GILL FULLER Dog Bottom, Lee Mill Road, Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire. Hon. Business Editor: Miss ANGELA KELLY 27 The Avenue, Muswell Hill, London N.10 (Tel. 01-883 9245) Hon. Hut Secretary: MRS. EVELYN LEECH Ty Gelan, Llansadwrn, Anglesey, (Tel. Beaumaris 287) Hon. Assistant Hut Secretary: Miss PEGGY WILD Plas Gwynant Adventure School, Nant Gwynant, Caernarvonshire (Tel.Beddgelert212) Committee: Miss S. CRISPIN Miss G. MOFFAT MRS. S ANGELL MRS. J. TAYLOR MRS. N. MORIN Hon. Auditor: Miss ANNETTE WILSON © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved CONTENTS Page Our Fiftieth Birthday ...... ...... Dorothy Pilley Richards 5 Wheel Full Circle ...... ...... Gwen M offat ...... 8 Climbing in the A.C.T. ...... Kath Hoskins ...... 14 The Early Days ..... ...... ...... Trilby Wells ...... 17 The Other Side of the Circus .... -

O Regon Section . Bob Mcgown, Section Chair, Was on Four

O r e g o n S e c t i o n . Bob McGown, Section chair, was on four continents this year, so Richard Bence took over some of his duties. Bence also maintains the Oregon Section and Madrone Wall Web sites, www.ors.alpine.org and www.savemadrone.org. The Oregon Section spon sors the Madrone Wall Web site. In a public study session, Clackamas County unanimously accepted the Parks Advisory Board recommendation not to sell the site for a private quarry or housing development and to move forward to establish a public park. Letters of support were written by over 500 citizens and by organizations including the Oregon Section. AAC member Keith Daellenbach is the founder and long time director of the Friends of Madrone Wall Pres ervation Committee. In late fall 2005 the Section sent $2,500 to Pakistan and collected tents and clothing that were shipped by the AAC. In January at the Hollywood Theater, Jeff Alzner organized the Cascade Mountain Film Festival, which raised an additional $6,000 for Pakistani relief efforts. Other contributions came from the Banff Film Festival participants who donated use of their films: Sandra Wroten and Gary Beck. There were also significant donations from Jill Kellogg, Jeff Alzner, Richard Bence, Richard Humphrey, Bob McGown, and others. Mazama president Wendy Carlton acted as MC in making the Pakistan Earthquake Village evening a success. We had over a dozen volunteers from the AAC and the Mazamas, and an estimated 350 people attended. The chair of Mercy Corps, headquartered in Portland, introduced the program. -

August 2017 RAMBLER

THE MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF THE WASATCH MOUNTAIN CLUB – AUGUST 2017 – VOLUME 96 NUMBER 8 1930 – 2017 Wasatch Mountain Club 2017-2018 PRESIDENT Julie Kilgore 801-244-3323 [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT Brett Matthews 801-831-5940 [email protected] TREASURERS Jason Anderson 385-355-0023 [email protected] Dave Rabiger 801-971-5836 [email protected] SECRETARY Barbara Boehme 801-633-1583 [email protected] BIKING CO-DIRECTORS Cindy Crass 801-803-1336 [email protected] Carrie Clark 801-931-4379 [email protected] Chris Winter 801-384-0973 [email protected] MOUNTAIN BIKING COORDINATOR Greg Libecci 801-699-1999 [email protected] BOATING CO-DIRECTORS Cindy Spangler 801-556-6241 [email protected] Tony Zimmer 440-465-2761 [email protected] BOATING EQUIPMENT CO-COORDINATORS Bret Mathews 801-831-5940 [email protected] Donnie Benson 801-466-5141 [email protected] CANOEING COORDINATOR Pam Stalnaker 801-425-9957 [email protected] RAFTING COORDINATOR Kelly Beumer 801-230-7969 [email protected] CLIMBING CO-DIRECTORS Mark Karpinski 801-886-7285 [email protected] Kathleen Waller 801-859-6689 [email protected] CANYONEERING COORDINATOR Rick Thompson [email protected] -

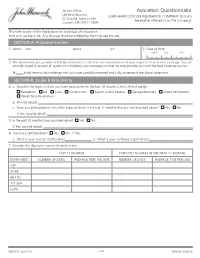

Avocation Questionnaire

Service Office: Avocation Questionnaire Life New Business JOHN HANCOCK LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY (U.S.A.) 30 Dan Rd, Suite 55765 (hereinafter referred to as The Company) Canton, MA 02021-2809 This form is part of the Application for Individual Life Insurance. Print and use black ink. Any changes must be initialed by the Proposed Insured. SECTION A: Proposed Insured 1. Name FIRST MIDDLE LAST 2. Date of Birth MONTH DAY YEAR 3. The information you provide in this Questionnaire is critical to our consideration of your request for insurance coverage. You are strongly urged to answer all questions completely and accurately so that we may provide you with the best coverage we can. X Initial here to acknowledge that you have carefully reviewed and fully understand the above statement. SECTION B: Scuba & Skin Diving 4. a. Describe the types of dives you have participated in the last 12 months (check all that apply): Recreation Ice Cave Construction Search and/or Rescue Salvage/Recovery Wreck Penetration Wreck Non-Penetration b. Provide details c. Have you participated in any other types of dives in the last 12 months that are not described above? Yes No If Yes, provide details 5. In the past 12 months, have you dived alone? Yes No If Yes, provide details 6. Are you a certified diver? Yes No If Yes, a. What is your level of certification? b. What is your certifying organization? 7. Describe the dives you have performed in the: LAST 12 MONTHS EXPECTED TO MAKE IN THE NEXT 12 MONTHS DEPTH (FEET) NUMBER OF DIVES AVERAGE TIME PER DIVE NUMBER OF DIVES AVERAGE TIME PER DIVE <30 30-65 66-130 131-200 >200 NB5010FL (03/2016) 1 of 4 VERSION (03/2016) SECTION C: Automobile, Motorcycle and Power Boat Racing 8. -

Exploring Grand Teton National Park

05 542850 Ch05.qxd 1/26/04 9:25 AM Page 107 5 Exploring Grand Teton National Park Although Grand Teton National Park is much smaller than Yel- lowstone, there is much more to it than just its peaks, a dozen of which climb to elevations greater than 12,000 feet. The park’s size— 54 miles long, from north to south—allows visitors to get a good look at the highlights in a day or two. But you’d be missing a great deal: the beautiful views from its trails, an exciting float on the Snake River, the watersports paradise that is Jackson Lake. Whether your trip is half a day or 2 weeks, the park’s proximity to the town of Jackson allows for an interesting trip that combines the outdoors with the urbane. You can descend Grand Teton and be living it up at the Million Dollar Cowboy Bar or dining in a fine restaurant that evening. The next day, you can return to the peace of the park without much effort at all. 1 Essentials ACCESS/ENTRY POINTS Grand Teton National Park runs along a north-south axis, bordered on the west by the omnipresent Teton Range. Teton Park Road, the primary thoroughfare, skirts along the lakes at the mountains’ base. From the north, you can enter the park from Yellowstone National Park, which is linked to Grand Teton by the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway (U.S. Hwy. 89/191/287), an 8-mile stretch of highway, along which you might see wildlife through the trees, some still bare and black- ened from the 1988 fires. -

Grand Teton National Park Wyoming

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR RAY LYMAN WILBUR. SECRETARY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HORACE M.ALBRIGHT. DIRECTOR CIRCULAR OF GENERAL INFORMATION REGARDING GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK WYOMING © Crandall THE WAY TO ENJOY THE MOUNTAINS THE GRAND TETON IN THE BACKGROUND Season from June 20 to September 19 1931 © Crandill TRIPS BY PACK TRAIN ARE POPULAR IN THE SHADOWS OF THE MIGHTY TETONS © Crandall AN IDEAL CAMP GROUND Mount Moran in the background 'Die Grand Teton National Park is not a part of Yellowstone National Park, and, aside from distant views of the mountains, can not be seen on any Yellowstone tour. It is strongly urged, how ever, that visitors to either park take time to see the other, since they are located so near together. In order to get the " Cathedral " and " Matterhorn " views of the Grand Teton, and to appreciate the grandeur and majestic beauty of the entire Teton Range, it is necessary to spend an extra day in this area. CONTENTS rage General description 1 Geographic features: The Teton Range 2 Origin of Teton Range 2 Jackson Hole 4 A meeting ground for glaciers .. 5 Moraines 6 Outwash plains 6 Lakes 6 Canyons 7 Peaks 7 How to reach the park: By automobile . 7 By railroad 9 Administration 0 Motor camping 11 Wilderness camping • 11 Fishing 11 Wild animals 12 Hunting in the Jackson Hole 13 Ascents of the Grand Teton 13 Rules and regulations 14 Map 18 Literature: Government publications— Distributed free by the National Park Service 13 Sold by Superintendent of Documents 13 Other national parks ' 19 National monuments 19 References 19 Authorized rates for public utilities, season of 1931 23 35459°—31 1 j II CONTENTS MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS COVER The way to enjoy the mountains—Grand Teton in background Outside front. -

A Climber's Guide to Townsville and Magnetic Island

Contents: Mt Stuart Castle Hill Minor Crags: West End Quarry Lazy Afternoon Wall University Wall Kissing Point Magnetic Island Front Cover: Curlew (23), Rocky Bay, Magnetic Island. Inside Front: Mt Stuart at dawn. Inside Back: Castle Hill at dawn. Back Cover: Physical Meditation(25), The Pinnacle, Mt Stuart. All photos by me unless acknowledged. Thanks to: everyone I’ve climbed with, especially Steve Baskerville and Jason Shaw for going to many of the minor crags with me; Scott Johnson for sending me a copy of his guide and other information; Lee Skidmore, Mark Gommers and Anthony Timms for going through drafts; Lee for letting me use slides and information from his Website; Andrew and Deb Thorogood for being very amenable employers and for letting me use their computer; Aussie Photographics whose cheap developing I recommend; Simon Thorogood for scanning the slides; the Army for letting us climb at Mt Stuart; the Rocks for being there and Tash for buying a computer and being lovely. Dedicated to Jason Shaw. Contact me at [email protected]. 1 Disclaimer Many of the climbs in this book have had few ascents. Rockclimbing is hazardous. The author accepts no responsibility for any inaccurate or incomplete information, nor for any controversial grading of climbs or dependance on fixed protection, some of which may be unreliable. This guide also assumes that users have a high level of ability, have received training from a skilled rockclimbing instructor, will use appropriate equipment properly and have care for personal safety. Also it should be obvious that large amounts of this publication are my opinion. -

1955 Number 13

Organized 1906 Incorporated 1913 The Mountaineer Volume 48 December 28, 1955 Number 13 Editor Boa KOEHLER Dear Mountaineer, This is your Annual. You-the Tacoma Editor climbers, viewfinders, trail trippers, BRUNHILDE WISLICENUS campcra£ters, skiers, photographers -made it possible because of your extensive programs throughout Everett Editors 1955. And some of you even took KE ' CARPENTER time to report your activities and GAIL CRUMMETT to prepare articles of general in GERTRUDE SCHOCK terest. To all of you, thanks a lot. There are a number of Moun Editorial Assistant taineers who, although their names MORDA c. SLAUSO do not appear on the masthead, contributed significantly to this Climbing Adviser yearbook. They are, of course, too DICK MERRITT numerous to mention. We hope you like our idea of issu Membership Editor ing the Annual after the hustle and LORETT A SLATER bustle of tl1e holiday season has passed. Membership Committee: Winifred A. Smith, Tacoma; Violet Johnson, Everett; If your yef1r of mountaineering Marguerite Bradshaw, Elenor Buswell, has been as rewarding as ours, Ruth Hobbs, Lee Snider, typists and then we know it has indeed been proofreaders. most successful. B. K. Advertising Typist: Shirley Cox COPYRIGHT 1955 BY THE MOUNTAINEERS, Inc. (1) CONTENTS General Articles CONQUERING THE WISHBONE ARETE-by Don Claunch .... .....................·-················-··· 7 ADVENTURING IN LEBANO -by Elizabeth Johriston ····-···············-··········-·······-····· 11 MouNT RAINIER IN I DIAN LEGE TDRY-by Ella E. Clark···········-······-·····-·-·······-··- 14 SOME CLIMBS IN THE TETONS-by Maury Muzzy·····--··-····--·-··-····-···--········-- 17 Wu,TER FuN FOR THE WEn-FooTED--by Everett Lasher_···-·····-··-··-····-··········-- 18 MIDSUMMER MAD rEss- an "Uncle Dudley". editorial .......·--······· ···-····--······--···-- 21 GLACIAL ADVANCES IN THE CASCADES-by Kermit Bengston and A. -

Modern Yosemite Climbing 219

MODERN YOSEMITE CLIMBING 219 MODERN YOSEMITE CLIMBING BY YVON CHOUINARD (Four illustrations: nos. 48-5r) • OSEMITE climbing is the least known and understood, yet one of the most important, schools of rock climbing in the world today. Its philosophies, equipment and techniques have been developed almost independently of the rest of the climbing world. In the short period of thirty years, it has achieved a standard of safety, difficulty and technique comparable to the best European schools. Climbers throughout the world have recently been expressing interest in Yosemit e and its climbs, although they know little about it. Until recently, even most American climbers were unaware of what was happening in their own country. Y osemite climbers in the past had rarely left the Valley to climb in other areas, and conversely few climbers from other regions ever come to Yosemite; also, very little has ever been published about this area. Climb after climb, each as important as a new climb done elsewhere, has gone completely unrecorded. One of the greatest rock climbs ever done, the 1961 ascent of the Salethe Wall, received four sentences in the American Alpine Journal. Just why is Y osemite climbing so different? Why does it have techniques, ethics and equipment all of its own ? The basic reason lies in the nature of the rock itself. Nowhere else in the world is the rock so exfoliated, so glacier-polished and so devoid of handholds. All of the climbing lines follow vertical crack systems. Nearly every piton crack, every handhold, is a vertical one. Special techniques and equipment have evolved through absolute necessity.