St Anford University Stanford, California 94305

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

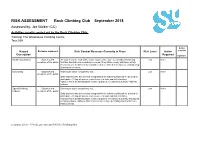

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018 Assessed by: Joe Walker (CC) Activities usually carried out by the Rock Climbing Club: Training: The Warehouse Climbing Centre Tour: N/A Action Hazard Persons exposed Risk Control Measures Currently in Place Risk Level Action complete Description Required signature Bouldering (Indoor) Students and All students of the club will be made aware of the safe use of indoor bouldering Low None members of the public facilities and will be immediately removed if they fail to comply with these safety measures or a member of the committee believe that their actions are endangering themselves or others. Auto-Belay Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay climbing indoors. Speed Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay and speed climbing indoors, ability to differentiate between speed climbing and normal auto belay systems. y:\sports\2018 - 19\risk assessments\UGSU Climbing RA Top Rope Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Med None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate in belaying - Fitting a harness, tying of a threaded figure of 8 knot, correct use of a belay device, correct belaying technique, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to top rope climbing indoors. -

Outdoor Retailer Summer Market 2019 Colorado Convention Center | Denver, Co Exhibitor List

OUTDOOR RETAILER SUMMER MARKET 2019 COLORADO CONVENTION CENTER | DENVER, CO EXHIBITOR LIST 4OCEAN, LLC ARCTIC COLLECTION AB BIG CITY MOUNTAINEERS 5.11 TACTICAL ARMBURY INC. BIG SKY INTERNATIONAL 7 DIAMONDS CLOTHING CO., INC. ART 4 ALL BY ABBY PAFFRATH BIMINI BAY OUTFITTERS, LTD. 7112751 CANADA, INC. ASANA CLIMBING BIOLITE 8BPLUS ASOLO USA, INC. BIONICA FOOTWEAR A O COOLERS ASSOCIATION OF OUTDOOR RECREATION & EDUCATION BIRKENSTOCK USA A PLUS CHAN CHIA CO., LTD. ASTRAL BUOYANCY CO. BISON DESIGNS, LLC A+ GROUP ATEXTILE FUJIAN CO LTD BITCHSTIX ABACUS HP ATOMICCHILD BLACK DIAMOND EQUIPMENT, LLC ABMT TEXTILES AUSTIN MEIGE TECH LLC BLISS HAMMOCKS, INC. ABSOLUTE OUTDOOR INC AUSTRALIA UNLIMITED INC. BLITZART, INC. ACCESS FUND AVALANCHE BLOQWEAR RETAIL ACHIEVETEX CO., LTD. AVALANCHE IP, LLC BLOWFISH LLC ACOPOWER AVANTI DESIGNS / AVANTI SHIRTS BLUE DINOSAUR ACT LAB, LLC BABY DELIGHT BLUE ICE NORTH AMERICA ADIDAS TERREX BACH BLUE QUENCH LLC ADVENTURE MEDICAL KITS, LLC BACKPACKER MAGAZINE - ADD LIST ONLY BLUE RIDGE CHAIR WORKS AEROE SPORTS LIMITED BACKPACKER MAGAZINE - AIM MEDIA BLUNDSTONE AEROPRESS BACKPACKER’S PANTRY BOARDIES INTERNATIONAL LTD AEROTHOTIC BAFFIN LTD. BOCO GEAR AETHICS BALEGA BODYCHEK WELLNESS AGS BRANDS BALLUCK OUTDOOR GEAR CORP. BODY GLIDE AI CARE LLC BAR MITTS BODY GLOVE IP HOLDINGS, LP AIRHEAD SPORTS GROUP BATES ACCESSORIES, INC. BOGS FOOTWEAR AKASO TECH, LLC BATTERY-BIZ BOKER USA INC. ALCHEMI LABS BC HATS, INC. BOOSTED ALEGRIA SHOES BDA, INC. BORDAN SHOE COMPANY ALIGN TEXTILE CO., LTD. BEAGLE / TOURIT BOTTLEKEEPER ALLIED FEATHER & DOWN BEAR FIBER, INC. BOULDER DENIM ALLIED POWERS LLC BEARDED GOAT APPAREL, LLC. BOUNDLESS NORTH ALOE CARE INTERNATIONAL, LLC BEARPAW BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA ALOHA COLLECTION, LLC BEAUMONT PRODUCTS INC BOYD SLEEP ALPS MOUNTAINEERING BED STU BRAND 44, LLC ALTERNATIVE APPAREL BEDFORD INDUSTRIES, INC. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior » , • National Park Service V National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts Sec instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" lor 'not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and area of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10- 900A). Use typewriter, word processor or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Camp 4 other name/site number Sunnyside Campground__________________________________________ 2. Location_______________________________________________________ street & number Northside Drive, Yosemite National Park |~1 not for publication city or town N/A [_xj vicinity state California code CA county Mariposa code 043 zip code 95389 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Itjiomination _irquest for determination of eligibility meets the documentationsJand»ds-iJar -

Analysis of the Accident on Air Guitar

Analysis of the accident on Air Guitar The Safety Committee of the Swedish Climbing Association Draft 2004-05-30 Preface The Swedish Climbing Association (SKF) Safety Committee’s overall purpose is to reduce the number of incidents and accidents in connection to climbing and associated activities, as well as to increase and spread the knowledge of related risks. The fatal accident on the route Air Guitar involved four failed pieces of protection and two experienced climbers. Such unusual circumstances ring a warning bell, calling for an especially careful investigation. The Safety Committee asked the American Alpine Club to perform a preliminary investigation, which was financed by a company formerly owned by one of the climbers. Using the report from the preliminary investigation together with additional material, the Safety Committee has analyzed the accident. The details and results of the analysis are published in this report. There is a large amount of relevant material, and it is impossible to include all of it in this report. The Safety Committee has been forced to select what has been judged to be the most relevant material. Additionally, the remoteness of the accident site, and the difficulty of analyzing the equipment have complicated the analysis. The causes of the accident can never be “proven” with certainty. This report is not the final word on the accident, and the conclusions may need to be changed if new information appears. However, we do believe we have been able to gather sufficient evidence in order to attempt an -

Ice and Mixed Festival Equipment Notes Chicks N Picks Ice Climbing Clinic

Ice and Mixed Festival Equipment Notes Chicks N Picks Ice Climbing Clinic Due to the nature of the mountain environment, equipment and clothing must be suitable for its intended purpose. It must be light, remain effective when wet or iced, and dry easily. These notes will help you make informed choices, which will save you time and money. Bring the mandatory clothing and wet weather gear, and any equipment you already own that is on the equipment checklist. This gives you an opportunity to practice with your gear and equipment, so that you become efficient at using it out in the field. Adventure Consultants is able to offer clients good prices on a range of clothing and equipment. Please feel free to contact us, if you need assistance with making a purchase or advice on specific products. BODY WEAR There are numerous fabrics, which are both water resistant and breathable such as Gore-Tex, Event, Polartec Neoshell, Pertex Shield and Entrant etc. These fabrics are expensive but can last for years if well looked after. Shell clothing should be seam sealed during the manufacturing process (tape sealed on the seams) or it will leak through the stitching. It also should be easy to move in and easy to put on and take off, when wearing gloves or mitts. Shell clothing made of PVC or similar totally waterproof non-breathable material is not suitable as moisture cannot escape when you are exerting energy, resulting in getting wet from the inside out! Therefore fabric breathability is very important when you are active in the mountains. -

4000 M Peaks of the Alps Normal and Classic Routes

rock&ice 3 4000 m Peaks of the Alps Normal and classic routes idea Montagna editoria e alpinismo Rock&Ice l 4000m Peaks of the Alps l Contents CONTENTS FIVE • • 51a Normal Route to Punta Giordani 257 WEISSHORN AND MATTERHORN ALPS 175 • 52a Normal Route to the Vincent Pyramid 259 • Preface 5 12 Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey 101 35 Dent d’Hérens 180 • 52b Punta Giordani-Vincent Pyramid 261 • Introduction 6 • 12 North Face Right 102 • 35a Normal Route 181 Traverse • Geogrpahic location 14 13 Gran Pilier d’Angle 108 • 35b Tiefmatten Ridge (West Ridge) 183 53 Schwarzhorn/Corno Nero 265 • Technical notes 16 • 13 South Face and Peuterey Ridge 109 36 Matterhorn 185 54 Ludwigshöhe 265 14 Mont Blanc de Courmayeur 114 • 36a Hörnli Ridge (Hörnligrat) 186 55 Parrotspitze 265 ONE • MASSIF DES ÉCRINS 23 • 14 Eccles Couloir and Peuterey Ridge 115 • 36b Lion Ridge 192 • 53-55 Traverse of the Three Peaks 266 1 Barre des Écrins 26 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable 117 37 Dent Blanche 198 56 Signalkuppe 269 • 1a Normal Route 27 15 L’Isolée 117 • 37 Normal Route via the Wandflue Ridge 199 57 Zumsteinspitze 269 • 1b Coolidge Couloir 30 16 Pointe Carmen 117 38 Bishorn 202 • 56-57 Normal Route to the Signalkuppe 270 2 Dôme de Neige des Écrins 32 17 Pointe Médiane 117 • 38 Normal Route 203 and the Zumsteinspitze • 2 Normal Route 32 18 Pointe Chaubert 117 39 Weisshorn 206 58 Dufourspitze 274 19 Corne du Diable 117 • 39 Normal Route 207 59 Nordend 274 TWO • GRAN PARADISO MASSIF 35 • 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable Traverse 118 40 Ober Gabelhorn 212 • 58a Normal Route to the Dufourspitze -

2001-2002 Bouldering Campaign

Climber: Angela Payne at Hound Ears Bouldering Comp Photo: John Heisel John Comp Photo: Bouldering Ears at Hound Payne Climber: Angela 2001-20022001-2002 BoulderingBouldering CampaignCampaign The Access Fund’s bouldering campaign hit bouldering products. Access Fund corporate and the ground running last month when a number community partners enthusiastically expressed of well-known climbers signed on to lend their their support for the goals and initiatives of support for our nationwide effort to: the bouldering campaign at the August •Raise awareness about bouldering among land Outdoor Retailer Trade Show held in Salt Lake managers and the public City. •Promote care and respect for natural places As part of our effort to preserve opportuni- visited by boulderers ties for bouldering, a portion of our grants pro- •Mobilize the climbing community to act gram will be targeted toward projects which responsibly and work cooperatively with land specifically address bouldering issues. Already, managers and land owners two grants that improve access and opportuni- •To protect and rehabilitate bouldering ties for bouldering have been awarded (more resources details about those grants can be found in this •Preserve bouldering access issue.) Grants will also be given to projects that •Help raise awareness and spread the message involve reducing recreational impacts at boul- about the campaign, inspirational posters fea- dering sites. The next deadline for grant appli- turing Tommy Caldwell, Lisa Rands and Dave cations is February 15, 2002. Graham are being produced that will include a Another key initiative of the bouldering simple bouldering “code of ethics” that encour- campaign is the acquisition of a significant ages climbers to: •Pad Lightly bouldering area under threat. -

Sunlight Peak Class 4 Exposure: Summit Elev

Sunlight Peak Class 4 Exposure: Summit Elev.: 14,066 feet Trailhead Elev.: 11,100 feet Elevation Gain: 3,000' starting at Chicago Basin 6,000' starting at Needleton RT Length: 5.00 miles starting at Chicago Basin 19 miles starting at Needleton Climbers: Rick, Brett and Wayne Crandall; Rick Peckham August 8, 2012 I’ve been looking at climbing reports to Sunlight Peak for a few years – a definite notch up for me, so the right things aligned and my son Brett (Class 5 climber), brother Wayne (strong, younger but this would be his first fourteener success) and friend Rick Peckham from Alaska converged with me in Durango to embark on a classic Colorado adventure with many elements. We overnighted in Durango, stocking up on “essential ingredients” for a two-night camp in an area called the Chicago Basin, which as you will see, takes some doing to get to. Durango, founded in 1880 by the Denver & Rio Grande Railway company, is now southwest Colorado’s largest town, with 15,000 people. Left to right: Brett, Rick, Wayne provisioning essentials. Chicago Basin is at the foot of three fourteeners in the San Juan range that can only be reached by taking Colorado’s historic and still running (after 130 years) narrow-gauge train from Durango to Silverton and paying a fee to get off with back-pack in the middle of the ride. Once left behind, the next leg of the excursion is a 7 mile back-pack while climbing 3000’ vertical feet to the Basin where camp is set. -

O Regon Section . Bob Mcgown, Section Chair, Was on Four

O r e g o n S e c t i o n . Bob McGown, Section chair, was on four continents this year, so Richard Bence took over some of his duties. Bence also maintains the Oregon Section and Madrone Wall Web sites, www.ors.alpine.org and www.savemadrone.org. The Oregon Section spon sors the Madrone Wall Web site. In a public study session, Clackamas County unanimously accepted the Parks Advisory Board recommendation not to sell the site for a private quarry or housing development and to move forward to establish a public park. Letters of support were written by over 500 citizens and by organizations including the Oregon Section. AAC member Keith Daellenbach is the founder and long time director of the Friends of Madrone Wall Pres ervation Committee. In late fall 2005 the Section sent $2,500 to Pakistan and collected tents and clothing that were shipped by the AAC. In January at the Hollywood Theater, Jeff Alzner organized the Cascade Mountain Film Festival, which raised an additional $6,000 for Pakistani relief efforts. Other contributions came from the Banff Film Festival participants who donated use of their films: Sandra Wroten and Gary Beck. There were also significant donations from Jill Kellogg, Jeff Alzner, Richard Bence, Richard Humphrey, Bob McGown, and others. Mazama president Wendy Carlton acted as MC in making the Pakistan Earthquake Village evening a success. We had over a dozen volunteers from the AAC and the Mazamas, and an estimated 350 people attended. The chair of Mercy Corps, headquartered in Portland, introduced the program. -

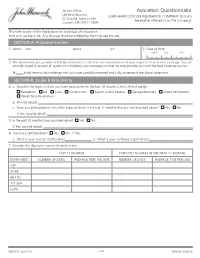

Avocation Questionnaire

Service Office: Avocation Questionnaire Life New Business JOHN HANCOCK LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY (U.S.A.) 30 Dan Rd, Suite 55765 (hereinafter referred to as The Company) Canton, MA 02021-2809 This form is part of the Application for Individual Life Insurance. Print and use black ink. Any changes must be initialed by the Proposed Insured. SECTION A: Proposed Insured 1. Name FIRST MIDDLE LAST 2. Date of Birth MONTH DAY YEAR 3. The information you provide in this Questionnaire is critical to our consideration of your request for insurance coverage. You are strongly urged to answer all questions completely and accurately so that we may provide you with the best coverage we can. X Initial here to acknowledge that you have carefully reviewed and fully understand the above statement. SECTION B: Scuba & Skin Diving 4. a. Describe the types of dives you have participated in the last 12 months (check all that apply): Recreation Ice Cave Construction Search and/or Rescue Salvage/Recovery Wreck Penetration Wreck Non-Penetration b. Provide details c. Have you participated in any other types of dives in the last 12 months that are not described above? Yes No If Yes, provide details 5. In the past 12 months, have you dived alone? Yes No If Yes, provide details 6. Are you a certified diver? Yes No If Yes, a. What is your level of certification? b. What is your certifying organization? 7. Describe the dives you have performed in the: LAST 12 MONTHS EXPECTED TO MAKE IN THE NEXT 12 MONTHS DEPTH (FEET) NUMBER OF DIVES AVERAGE TIME PER DIVE NUMBER OF DIVES AVERAGE TIME PER DIVE <30 30-65 66-130 131-200 >200 NB5010FL (03/2016) 1 of 4 VERSION (03/2016) SECTION C: Automobile, Motorcycle and Power Boat Racing 8. -

CLIMBING ETHICS Alpine Style Vs Commercial Expeditions

p i o l e T s d ’ o r 2 0 0 9 81 CLIMBING ETHICS Alpine Style vS CommerCiAl expeditionS The opening night of the Piolets d’Or included a discussion on Climbing Ethics. Here, mountain guide Victor Saunders expands on his contribution to that spir- ited debate. There are those who think commercial expeditions are unethical, that commercial expeditions should use alpine-style tactics, and that maybe they should not exist at all. I will show that this view is mistaken and that the ethical issue is in fact irrelevant; but before dealing with the so-called ethical issue, I wish to set aside the usual diversions that get mixed up in this discussion. There are three that I commonly hear: First: Commercial expeditions bring too many people to the same moun- tain, by the same route. Well, to these people I say, if you have a romantic desire to find raw nature, go away and do new routes on unclimbed moun- tains. Let the wonderful climbs that have been nominated for this year’s Piolets d’Or inspire you. It is not intelligent to do the normal route on Mont Blanc in August and complain that you are not alone. Second: The environmental thing. Commercial expeditions typically go back to the same site year after year, and so it is in the operator’s inter- est to keep camps clean and tidy for the next visit. Amateur expeditions rely solely on the good moral values of the climbers, because there are no other controls on them. -

Sometimes the Leader Does Fall... a Look Into the Experiences of Ice Climbers Who Have Fallen on Ice Screws

SOMETIMES THE LEADER DOES FALL... A LOOK INTO THE EXPERIENCES OF ICE CLIMBERS WHO HAVE FALLEN ON ICE SCREWS Kel Rossiter Ed.D., Educational Leadership & Policy Studies--M.S., Kinesiology/Outdoor Education AMGA Certified Rock & Alpine Guide INTRODUCTION/BACKGROUND Last winter a climber with Adventure Spirit Rock+Ice+Alpine was asking me about the holding power of ice screws. We discussed the various lab studies that have been done (a list of links to some interesting ones can be found at the bottom of this paper) then he said, “That's great, but has anyone ever specifically done research into how they actually perform in the field?” He had a point. While the dictum in ice climbing is that “the leader never falls,” in the end, they sometimes do. So presumably there was an ample population from which to sample— but I was unaware of any actual field research done with this population. So, fueled by that question, I decided to explore the topic. The results of this inquiry appear below. Though I have a background in research, make no mistake: This presentation of findings should not be viewed through the same lens as academic research. Aside from running it by a few academic-climber friends there has been only an informal peer review, there are significant short-comings in the methodology (noted below), and ideas are put forth that don't necessarily build directly on prior research (largely because—as noted—there really hasn't been much research on the topic and much less field research). In addition, this write up is not done in the typical “5 Part” research format of Introduction, Methodology, Results, Analysis, and Conclusion.