Lions on the Beach, Whales in the Jungle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

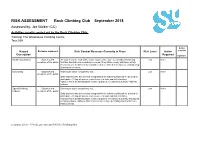

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018 Assessed by: Joe Walker (CC) Activities usually carried out by the Rock Climbing Club: Training: The Warehouse Climbing Centre Tour: N/A Action Hazard Persons exposed Risk Control Measures Currently in Place Risk Level Action complete Description Required signature Bouldering (Indoor) Students and All students of the club will be made aware of the safe use of indoor bouldering Low None members of the public facilities and will be immediately removed if they fail to comply with these safety measures or a member of the committee believe that their actions are endangering themselves or others. Auto-Belay Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay climbing indoors. Speed Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay and speed climbing indoors, ability to differentiate between speed climbing and normal auto belay systems. y:\sports\2018 - 19\risk assessments\UGSU Climbing RA Top Rope Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Med None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate in belaying - Fitting a harness, tying of a threaded figure of 8 knot, correct use of a belay device, correct belaying technique, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to top rope climbing indoors. -

Mcofs Climbing Wall Specifications

THE MOUNTAINEERING COUNCIL OF SCOTLAND The Old Granary West Mill Street Perth PH1 5QP Tel: 01738 493 942 Website: www.mcofs.org.uk SCOTTISH CLIMBING WALLS: Appendix 3 Climbing Wall Facilities: Specifications 1. Climbing Wall Definitions 1.1 Type of Wall The MCofS recognises the need to develop the following types of climbing wall structure in Scotland. These can be combined together at a suitably sized site or developed as separate facilities (e.g. a dedicated bouldering venue). All walls should ideally be situated in a dedicated space or room so as not to clash with other sporting activities. They require unlimited access throughout the day / week (weekends and evenings till late are the most heavily used times). It is recommended that the type of wall design is specific to the requirements and that it is not possible to utilise one wall for all climbing disciplines (e.g. a lead wall cannot be used simultaneously for bouldering). For details of the design, development and management of walls the MCofS supports the recommendations in the “Climbing Walls Manual” (3rd Edition, 2008). 1.1.1. Bouldering walls General training walls with a duel function of allowing for the pursuit of physical excellence, as well as offering a relatively safe ‘solo’ climbing experience which is fun and perfect for a grass-roots introduction to climbing. There are two styles: indoor venues and outdoor venues to cater for the general public as a park or playground facility (Boulder Parks). Dedicated bouldering venues are particularly successful in urban areas* where local access to natural crags offering this style of climbing is not available. -

Wrestling with Liability: Encouraging Climbing on Private Land Page 9

VERTICAL TIMESSection The National Publication of the Access Fund Winter 09/Volume 86 www.accessfund.org Wrestling with Liability: Encouraging Climbing on Private Land page 9 CHOOSING YOUR COnseRvatION STRateGY 6 THE NOTORIOUS HORsetOOTH HanG 7 Winter 09 Vertical Times 1 QUeen CReeK/OaK Flat: NEGOTIATIONS COntINUE 12 AF Perspective “ All the beautiful sentiments in the world weigh less than a single lovely action.” — James Russell Lowell irst of all, I want to take a moment to thank you for all you’ve done to support us. Without members and donors like you, we would fall short F of accomplishing our goals. I recently came across some interesting statistics in the Outdoor Foundation’s annual Outdoor Recreation Participation Report. In 2008, 4.7 million people in the United States participated in bouldering, sport climbing, or indoor climbing, and 2.3 million people went trad climbing, ice climbing, or mountaineering. It is also interesting to note that less than 1% of these climbers are members of the Access Fund. And the majority of our support comes from membership. We are working on climbing issues all across the country, from California to Maine. While we have had many successes and our reach is broad, just imagine what would be possible if we were able to increase our membership base: more grants, more direct support of local climbing organizations, and, ultimately, more climbing areas open and protected. We could use your help. Chances are a number of your climbing friends and partners aren’t current Access Fund members. Please take a moment to tell them about our work and the impor- tance of joining us, not to mention benefits like discounts on gear, grants for local projects, timely information and alerts about local access issues, and a subscrip- tion to the Vertical Times. -

8Th December 2017 SPEED, BOULDERING & LEAD AFRICAN

1 8th December 2017 SPEED, BOULDERING & LEAD AFRICAN YOUTH A SELECTION COMPETITION Johannesburg, South Africa FOR SELECTION TO COMPETE IN THE 2018 YOUTH OLYMPIC GAMES 2 ORGANIZATION • Host Federation: South African National Climbing Federation (SANCF) • Organizing Federation: South African National Climbing Federation (SANCF) with the assistance of Gauteng Climbing The African Youth “A” Selection Competition is organized by the SANCF in accordance with the IFSC regulations for athletes born between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2001. COMPETITION VENUE 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 2. Acknowledgement of Sponsors and Hosts.......................................................................................... 5 3. Date of 2017 African Selection Competition for the 2018 YOG .......................................................... 5 4. Venue ................................................................................................................................................. 5 5. Refreshments ..................................................................................................................................... 5 6. Prize Giving ......................................................................................................................................... 6 7. Pre-Competition Non-Competitor Meetings. .................................................................................... -

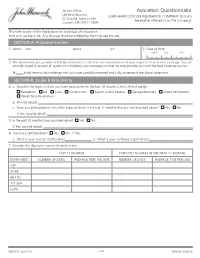

Avocation Questionnaire

Service Office: Avocation Questionnaire Life New Business JOHN HANCOCK LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY (U.S.A.) 30 Dan Rd, Suite 55765 (hereinafter referred to as The Company) Canton, MA 02021-2809 This form is part of the Application for Individual Life Insurance. Print and use black ink. Any changes must be initialed by the Proposed Insured. SECTION A: Proposed Insured 1. Name FIRST MIDDLE LAST 2. Date of Birth MONTH DAY YEAR 3. The information you provide in this Questionnaire is critical to our consideration of your request for insurance coverage. You are strongly urged to answer all questions completely and accurately so that we may provide you with the best coverage we can. X Initial here to acknowledge that you have carefully reviewed and fully understand the above statement. SECTION B: Scuba & Skin Diving 4. a. Describe the types of dives you have participated in the last 12 months (check all that apply): Recreation Ice Cave Construction Search and/or Rescue Salvage/Recovery Wreck Penetration Wreck Non-Penetration b. Provide details c. Have you participated in any other types of dives in the last 12 months that are not described above? Yes No If Yes, provide details 5. In the past 12 months, have you dived alone? Yes No If Yes, provide details 6. Are you a certified diver? Yes No If Yes, a. What is your level of certification? b. What is your certifying organization? 7. Describe the dives you have performed in the: LAST 12 MONTHS EXPECTED TO MAKE IN THE NEXT 12 MONTHS DEPTH (FEET) NUMBER OF DIVES AVERAGE TIME PER DIVE NUMBER OF DIVES AVERAGE TIME PER DIVE <30 30-65 66-130 131-200 >200 NB5010FL (03/2016) 1 of 4 VERSION (03/2016) SECTION C: Automobile, Motorcycle and Power Boat Racing 8. -

Strategy for Tourism Development in Protected Areas in Georgia

STRATEGY FOR TOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN PROTECTED AREAS IN GEORGIA Transboundary Joint Secretariat for the Southern Caucasus ASSESSING AND DEVELOPING THE ECO-TOURISM POTENTIAL OF THE PROTECTED AREAS IN GEORGIA Contract number: 2008.65.550 / 2013.11.001 Version: Final 26.03.2015 Issue/Version No.: Final Contract No.: 2008.65.550 / 2013.11.001 Date: 26.03.2015 Authors: Janez Sirse/Lela Kharstishvili Contact Information: Paula Ruiz Rodrigo Österreichische Bundesforste AG Consulting Pummergasse 10-12 3002 Purkersdorf Austria T: +43 2231 600 5570 F: +43 2231 600 5509 [email protected] www.oebfconsulting.at Financed by: Transboundary Joint Secretariat/APA ASSESSING AND DEVELO PING THE ECO - TOURISM POTENTIAL OF T H E PROTECTED AREA S IN GEORGIA TOURISM STRATEGY - FINAL CONTENT ANNEXES ....................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................ iv LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................. v ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................... vi 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 8 2 METHODLOGY .................................................................................................. 10 3 PROTECTED AREAS AND PROFILE OF SELECTED -

A Climber's Guide to Townsville and Magnetic Island

Contents: Mt Stuart Castle Hill Minor Crags: West End Quarry Lazy Afternoon Wall University Wall Kissing Point Magnetic Island Front Cover: Curlew (23), Rocky Bay, Magnetic Island. Inside Front: Mt Stuart at dawn. Inside Back: Castle Hill at dawn. Back Cover: Physical Meditation(25), The Pinnacle, Mt Stuart. All photos by me unless acknowledged. Thanks to: everyone I’ve climbed with, especially Steve Baskerville and Jason Shaw for going to many of the minor crags with me; Scott Johnson for sending me a copy of his guide and other information; Lee Skidmore, Mark Gommers and Anthony Timms for going through drafts; Lee for letting me use slides and information from his Website; Andrew and Deb Thorogood for being very amenable employers and for letting me use their computer; Aussie Photographics whose cheap developing I recommend; Simon Thorogood for scanning the slides; the Army for letting us climb at Mt Stuart; the Rocks for being there and Tash for buying a computer and being lovely. Dedicated to Jason Shaw. Contact me at [email protected]. 1 Disclaimer Many of the climbs in this book have had few ascents. Rockclimbing is hazardous. The author accepts no responsibility for any inaccurate or incomplete information, nor for any controversial grading of climbs or dependance on fixed protection, some of which may be unreliable. This guide also assumes that users have a high level of ability, have received training from a skilled rockclimbing instructor, will use appropriate equipment properly and have care for personal safety. Also it should be obvious that large amounts of this publication are my opinion. -

Monster Tribune3 24-01-2006 10:05 Pagina 1

Monster tribune3 24-01-2006 10:05 Pagina 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K INTERNATIONAL THE WORLD’S NEWSPAPER PUBLISHED BY GRIVEL MONT BLANC EDITED IN COURMAYEUR AND PRINTED IN MORGEX Winter 2006 - n°3 Two newborns in the Grivel family The Family is growing In 2006 two new members have been added to the Monster line. Alp Monster for alpinists, climbers and dry toolers. Lil’Monster for beginners, light weighters, hand protectable. MONSTER ALP MONSTER Once upon a time there was a beast, The most recent revolution, the Monster, comes to A new or more exactly a Monster, that the light in 2004. version decided to start climbing ice and Experts in competition climbing, bouldering, extreme of mountains. All the wise old men of dry tooling, total dry will immediately recognise the Monster Monster for what it is, not a new ice axe, but the with a the village said “ no you can’t climb most efficient extension of their own arm for hooking hammer for the ice and mountains because you’re on the most difficult terrains. The shaft has multiple alpinists, ice climbers not strong enough, you’re a weakling. grips for traction, swings, hand swap-overs, new and dry toolers. Ideal You’re all skinny and flat with positions and interpretations: all power to imagination! substitute for an ice axe humps …. you’re just a Monster! Forged pick with teeth at all angles, straight, inverse, when manageability and But he didn’t give up: he tried and into holes, onto the tiniest holds. -

How Not to Train Top 5 Moderate Desert Spires

THE PUSH AN EXCERPT FROM TOMMY CALDWELL’S NEW MEMOIR FIRST THE RED FEMALE RIVER GORGE’S SECRET 5.15 PAST HAYES MAKES HISTORY TECH TIPS TRAIN ENDURANCE EAT SMARTER, SEND HARDER LOWER IN TOP 5 MODERATE GUIDE MODE DESERT SPIRES HOW NOT TO TRAIN (HINT: IT’S EASIER THAN YOU THINK) Fabian Buhl Fabian © 2017 adidas AG Andreas Steindl Andreas OUTPERFORM THE WIND The TERREX AGRAVIC ALPHA HOODED SHIELD jacket protects you from the wind while keeping your body at the optimal temperature. Whether you perform high pulse or static movements, always stay in your most comfortable zone while pushing your limits further. Andrew Taylor Andrew adidasoutdoor.com all new features EASY OPEN/CLOSE 1 LEAK-PROOF CAP LEAK-PROOF 2 ON/OFF LEVER Water when you want it, none when you don’t. 20% MORE 3 WATER PER SIP Faster water flow powers longer adventures. ERGONOMIC 4 HANDLE Perfect for one-hand filling. HOW TO FIX SOMETHING THAT ISN’T THE LEAST BIT BROKEN. Why upgrade to a new camelbak crux when an old CamelBak Reservoir will last forever? Because we never stop innovating. Our new Crux reservoir delivers 20% more water with every sip in a pack loaded with the latest in hydration technology. camelbak.com CONTENTS 8 FLASH 22 THE APPROACH 17 EDITOR’S NOTE 20 OFF THE WALL Latino Outdoors is engaging the Lati- no community in outdoor recreation. 21 UNBELAYVABLE THE CLIMB 22 TALK OF THE CRAG Climbers, federal agencies, and locals are working to preserve Joe’s Valley. 24 PORTRAIT Kris Hampton’s rise from a rough past to coaching stardom. -

2018 Sport and Speed Season Team Handbook

2018 Sport and Speed Season Team Handbook Name: ______________________________ Boulders Climbing Team Mission: Boulders Climbing Team’s mission is to develop competent athletes to a degree that fosters a love for the sport, encourages having fun, and emphasizes the importance of independent thinking and being resilient when faced with failure. About: Boulders Climbing Team shapes kids into responsible, informed climbers. Athletes will begin with an introduction to techniques that continue to be developed with progression through our program. Being a part of Boulders Climbing Team teaches athletes life skills such as discipline, responsibility, self-awareness, and resilience. Athletes can expect coaches to encourage them to challenge their limits and see just how far they can push themselves. By the end of their time with Boulders Climbing Team, athletes will understand and practice a Leave No Trace ethic, determine and perform adequately difficult drills for themselves, and be an active, competent member of the growing climbing community. Coaches: Caleb Fitzgerald (Head Coach), Erin Ayla, Sofie Schachter, Kayla Ellenbecker, Ian Cotter-Brown, and Ben Ellis. Tryouts: Boulders Climbing Team is by invitation only and requires a tryout. Tryouts are used to ensure each athlete is placed on the team best fit to their skills and abilities. All climbers, regardless of prior participation on Boulders Climbing Team, must tryout for a spot on team. Tryouts will run in late August before the beginning of bouldering season and in late January before the beginning of sport and speed season. Tryouts at other times in the season can be arranged with the Head Coach. During tryouts, climbers are assessed relative to their peers. -

Current Understanding in Climbing Psychophysiology Research

Current understanding in climbing psychophysiology research Item Type Article Authors Giles, David; Draper, Nick; Gilliver, Peter; Taylor, Nicola; Mitchell, James; Birch, Linda; Woodhead, Joseph; Blackwell, Gavin; Hamlin, Michael J. Citation Giles, D. et al (2014) 'Current understanding in climbing psychophysiology research', Sports Technology, 7 (3-4):108 DOI 10.1080/19346182.2014.968166 Journal Sports Technology Rights Archived with thanks to Sports Technology Download date 02/10/2021 04:24:36 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/620534 RTEC 968166—9/10/2014—CHANDRAN.C—495943 Sports Technology, 2014 Vol. 00, No. 0, 1–12, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19346182.2014.968166 1 58 2 59 3 REVIEW 60 4 61 5 62 6 63 7 Current understanding in climbing psychophysiology research 64 8 65 9 66 10 67 1 1,2 1 1 11 DAVID GILES , NICK DRAPER , PETER GILLIVER , NICOLA TAYLOR , 68 12 1 1 3 2 69 JAMES MITCHELL , LINDA BIRCH , JOSEPH WOODHEAD , GAVIN BLACKWELL ,& 13 4 70 MICHAEL J. HAMLIN 14 71 15 1 2 72 School of Sports Performance and Outdoor Leadership, University of Derby, Buxton, United Kingdom, School of Sport and 16 3 73 Physical Education, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, School of Sport and Exercise Science, The 17 4 74 University of Chichester, Chichester, United Kingdom and Department of Social Science, Parks, Recreation, Tourism & Sport, 18 75 Lincoln University, Christchurch, New Zealand 19 76 20 77 (Received 14 March 2014; accepted 19 August 2014) 21 78 22 79 23 80 24 Abstract 81 25 The sport of rock climbing places a significant physiological and psychological load on participants. -

Addendum D to USA Climbing Rulebook 2020-2021 V1.0

Addendum D to USA Climbing Rulebook 2020-2021 v1.0 USA Climbing Rulebook 2020-2021 v1.0 Addendum D – 20210526 USA Climbing Rulebook Addendum This Rulebook Addendum shall be read in conjunction with USA Climbing Rulebook 2020-2021 v1.0, and shall remain in effect until a subsequent addendum or version has been published. Any amendments to these rules will be published on the USA Climbing website www.usaclimbing.org and shall be read in conjunction with and shall take precedence over the original document. This Rulebook Addendum is subject to approval by the Board of Directors of USA Climbing in consultation with the Chief Executive Officer. In the event of any conflict between USA Climbing’s Bylaws and this Rulebook, USA Climbing’s Bylaws will control. USA Climbing Contact Information Email: [email protected] | Phone: 303-499-0715 | Fax: 561-423-0715 Mail: USA Climbing | 537 W 600 S Suite #300 | Salt Lake City, UT 84101 Rules Committee: The Rules Committee shall be responsible for maintaining and updating the Rulebook(s) for the organization, as well as keeping current with IFSC standards and practices. The Rules Committee may be reached via e-mail: [email protected]. 2 USA Climbing Rulebook 2020-2021 v1.0 Addendum D – 20210526 Rulebook Addendum In response to the current COVID global pandemic, USA Climbing has updated or replaced select rules in the Rulebook, in particular those rules related to the Youth and Collegiate Bouldering, Lead/TR and Speed Qualification Series. This USA Climbing Rulebook Addendum D (Rulebook Addendum), which replaces all prior Addenda, each in its entirety, is to be read in conjunction with USA Climbing Rulebook 2020-2021 v1.0 (Rulebook), and represents a portion of USA Climbing’s response to the COVID global pandemic.