Climbing the City. Inhabiting Verticality Outside of Comfort Bubbles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

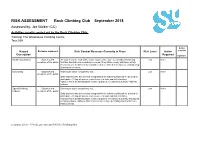

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018 Assessed by: Joe Walker (CC) Activities usually carried out by the Rock Climbing Club: Training: The Warehouse Climbing Centre Tour: N/A Action Hazard Persons exposed Risk Control Measures Currently in Place Risk Level Action complete Description Required signature Bouldering (Indoor) Students and All students of the club will be made aware of the safe use of indoor bouldering Low None members of the public facilities and will be immediately removed if they fail to comply with these safety measures or a member of the committee believe that their actions are endangering themselves or others. Auto-Belay Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay climbing indoors. Speed Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay and speed climbing indoors, ability to differentiate between speed climbing and normal auto belay systems. y:\sports\2018 - 19\risk assessments\UGSU Climbing RA Top Rope Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Med None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate in belaying - Fitting a harness, tying of a threaded figure of 8 knot, correct use of a belay device, correct belaying technique, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to top rope climbing indoors. -

Six Adventure Road Trips

Easy Drives, Big Fun, and Planning Tips Six Adventure Road Trips DAY HIKES, FLY-FISHING, SKIING, HISTORIC SITES, AND MUCH MORE A custom guidebook in partnership with Montana Offi ce of Tourism and Business Development and Outside Magazine Montana Contents is the perfect place for road tripping. There are 3 Glacier Country miles and miles of open roads. The landscape is stunning and varied. And its towns are welcoming 6 Roaming the National Forests and alluring, with imaginative hotels, restaurants, and breweries operated by friendly locals. 8 Montana’s Mountain Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks are Biking Paradise the crown jewels, but the Big Sky state is filled with hundreds of equally awesome playgrounds 10 in which to mountain bike, trail run, hike, raft, Gateways to Yellowstone fish, horseback ride, and learn about the region’s rich history, dating back to the days of the 14 The Beauty of Little dinosaurs. And that’s just in summer. Come Bighorn Country winter, the state turns into a wonderland. The skiing and snowboarding are world-class, and the 16 Exploring Missouri state offers up everything from snowshoeing River Country and cross-country skiing to snowmobiling and hot springs. Among Montana’s star attractions 18 Montana on Tap are ten national forests, hundreds of streams, tons of state parks, and historic monuments like 20 Adventure Base Camps Little Bighorn Battlefield and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. Whether it’s a family- 22 friendly hike or a peaceful river trip, there’s an Montana in Winter experience that will recharge your spirit around every corner in Montana. -

Alex Honnold at the International Mountain Summit.Pdf

Pressebüro | Ufficio stampa | Press office IMS - International Mountain Summit Contact: Erica Kircheis | +39 347 6155011 | [email protected] Brennerstraße 28 | Via Brennero 28 | I-39042 Brixen/Bressanone [email protected] | www.ims.bz Alex Honnold, the first (and for now the only) to climb the big wall on El Capitan without rope will be gueststar at the International Mountain Summit in Bressanone/South Tyrol (Italy) A great step for Mountaineering has been made. After his incredible free solo climbing of 1,000 meters of El Capitan, Alex Honnold will participate in the IMS in Bressanone. Now ticket office is open. Alex Honnold started to climb as a child at the age of 11 . The passion for this sport grew with him so much that at 18 he interrupted his studies at Berkeley to dedicate himself exclusively to climbing. This was the beginning of his life as a professional climber. Honnold is known as much for his humble, self-effacing attitude as he is for the dizzyingly tall cliffs he has climbed without a rope to protect him if he falls. “I have the same hope of survival as everybody else. I just have more of an acceptance that I will die at some point”, extreme climber A lex Honnold said in an interview with National Geographic. Honnold is considered the best free solo climber in the world and holds several speed records, for instance for El Capitan in Yosemite National Park in California, which he climbed a few weeks ago in less than 4 hours without rope or any other protection. -

WORLDWIDE TRAVEL INSURANCE Sports and Activities Endorsement

Page 1 of 2 WORLDWIDE TRAVEL INSURANCE Sports and Activities Endorsement ACTIVITY ENDORSEMENT SCHEDULE APPLYING TO ALL 1. Section 4, Personal Accident - excluded entirely whilst participating in the following types of activities: airborne; ACTIVITIES potholing; canyoning; higher risk wintersports; professional sports; whilst working. Otherwise limited to £5,000. 2. Section 2, Medical & other expenses - Excess increased to £100 each and every claim resulting directly or indirectly from participation in an activity. 3. Section 10, Personal Liability - You are not covered for any liability for bodily injury, loss or damage that you may cause to someone else, including other players/participants, or their property whilst participating in an activity. 4. You are not covered unless you adhere to the rules set by any Governing Body (or equivalent authority) of the Declared Activity, observe all normal safety precautions and use all recommended protective equipment and clothing. AIRBORNE SPORTS You are not covered: 1. under any Section whilst practising for or taking part in competitive flying, aerobatics or racing 2. for ‘base jumping’ from man-made features. In respect of piloting or flying in light aircraft: a) You are not covered whilst practising for or taking part in competitive flying, aerobatics or racing. b) Initial pilot training prior to obtaining PPL is subject to payment of twice the normal additional premium. CLIMBING, 1. Section 2, Medical & other expenses is extended to cover the cost of rescue or recovery by a recognised rescue TREKKING, service, either to prevent or following injury or illness, not exceeding £5,000 in total for all people insured by us. -

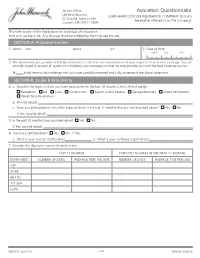

Avocation Questionnaire

Service Office: Avocation Questionnaire Life New Business JOHN HANCOCK LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY (U.S.A.) 30 Dan Rd, Suite 55765 (hereinafter referred to as The Company) Canton, MA 02021-2809 This form is part of the Application for Individual Life Insurance. Print and use black ink. Any changes must be initialed by the Proposed Insured. SECTION A: Proposed Insured 1. Name FIRST MIDDLE LAST 2. Date of Birth MONTH DAY YEAR 3. The information you provide in this Questionnaire is critical to our consideration of your request for insurance coverage. You are strongly urged to answer all questions completely and accurately so that we may provide you with the best coverage we can. X Initial here to acknowledge that you have carefully reviewed and fully understand the above statement. SECTION B: Scuba & Skin Diving 4. a. Describe the types of dives you have participated in the last 12 months (check all that apply): Recreation Ice Cave Construction Search and/or Rescue Salvage/Recovery Wreck Penetration Wreck Non-Penetration b. Provide details c. Have you participated in any other types of dives in the last 12 months that are not described above? Yes No If Yes, provide details 5. In the past 12 months, have you dived alone? Yes No If Yes, provide details 6. Are you a certified diver? Yes No If Yes, a. What is your level of certification? b. What is your certifying organization? 7. Describe the dives you have performed in the: LAST 12 MONTHS EXPECTED TO MAKE IN THE NEXT 12 MONTHS DEPTH (FEET) NUMBER OF DIVES AVERAGE TIME PER DIVE NUMBER OF DIVES AVERAGE TIME PER DIVE <30 30-65 66-130 131-200 >200 NB5010FL (03/2016) 1 of 4 VERSION (03/2016) SECTION C: Automobile, Motorcycle and Power Boat Racing 8. -

Climbing Dating

Fitness Singles is the best club to meet Rock Climbing Singles!Whether you are looking for love or simply a fitness partner, we are the Rock Climbing Dating site for renuzap.podarokideal.ruer now for FREE to search through our database of thousands of Rock Climbing Personals by zip code, fitness category, keywords or recent activity. You’ll soon understand why thousands of active singles join our. Climbing dating site - Is the number one destination for online dating with more dates than any other dating or personals site. Register and search over 40 million singles: matches and more. If you are a middle-aged man looking to have a good time dating woman half your age, this advertisement is for you. Find Climbing and Mountaineering Partners. Searching for someone who shares your passion for climbing or mountaineering? Whether you are just looking for an active friend to share a rope, or to meet someone special, this is the right place to find a partner. Connect with a bevy of outdoorsy singles who are passionate about mountain climbing. Join our club at Outdoor Dating Mountain Climbing and set up a few dates!, Outdoor Dating - Mountain Climbing. This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies. OK More info. Jun 17, · Dating is hard enough as it is, and I find that I'm only interested in dating a "climber." I'd hate to put a ceiling on possibility by having specific criteria but with most of my bandwidth focused on climbing, gear, trips, the prospect of jumping etc. -

Mountain Bike Trail Development Concept Plan

Mountain Bike Trail Development Concept Plan Prepared by Rocky Trail Destination A division of Rocky Trail Entertainment Pty Ltd. ABN: 50 129 217 670 Address: 20 Kensington Place Mardi NSW 2259 Contact: [email protected] Ph 0403 090 952 In consultation with For: Lithgow City Council 2 Page Table of Contents 1 Project Brief ............................................................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Project Management ....................................................................................................................... 7 About Rocky Trail Destination .......................................................................................................... 7 Who we are ......................................................................................................................................... 7 What we do .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Key personnel and assets ................................................................................................................. 8 1.2 Project consultant .......................................................................................................................... 11 Project milestones 2020 .................................................................................................................. 11 2 Lithgow as a Mountain Bike Destination ........................................................................................... -

2021 FIA Motorsport Games: Drifting Cup – Sporting Regulations

2021 FIA MSG: Drifting Cup Sporting Regulations – Approved by WMSC 05.03.2021 _________________________________________________________________________________________ 2021 FIA Motorsport Games: Drifting Cup – Sporting Regulations INTRODUCTION 3 GENERAL INFORMATION 3 COMPETITION DIVISIONS 1. COMPETITION PARTICIPANTS 3 2. COMPETITION CATEGORY 3 3. ENTRY PROCEDURE 4 3.1 COMPETITOR APPLICATIONS 4 3.2 COMPETITOR NATIONALITY 4 3.3 COMPETITOR ELIGIBILITY 4 4. FIA MOTORSPORT GAMES: DRIFTING CUP TITLE 4 5. FIA MOTORSPORT GAMES 5 COMPETITION OFFICIALS 6. COMPETITION OFFICIALS 5 6.1 STEWARDS 5 6.2 CLERK OF THE COURSE AND/OR RACE DIRECTOR 6 6.3 EVENT SECRETARY 6 6.4 TECHNICAL DELEGATE AND/OR CHIEF SCRUTINEER 6 6.5 JUDGES 6 PENALTIES 7. PENALTIES 7 GENERAL PROVISIONS 8. GENERAL PROVISIONS 8 9. COMPETITION NUMBERS AND ADVERTISING ON CARS 8 9.1 COMPETITION NUMBERS 8 9.2 COMPETITION BRANDING 8 9.3 ADVERTISING ON CARS 8 10. SAFETY 8 10.1 GENERAL SAFETY 8 10.2 TRACK CONTROL 9 11. INSURANCE 9 11.1 EVENT INSURANCE 9 11.2 PERSONAL INSURANCE 10 12. SIGNALIZATION 10 13. ADMINISTRATIVE CHECK 10 14. SCRUTINEERING 10 14.1 GENERAL SCRUNTINEERING PRACTICES AND REQUIREMENTS 10 14.2. NOISE RESTRICTIONS 11 COMPETITION 15. BRIEFING 11 16. PRACTICE 11 17. COMPETITION 12 __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Updated on: 12/02/2021 1/34 2021 FIA MSG: Drifting Cup Sporting Regulations – Approved by WMSC 05.03.2021 _________________________________________________________________________________________ 18. START LINE PROCEDURE 12 19. QUALIFICATION 13 19.1 QUALIFYING FORMAT 13 19.2 INITIATION DURING QUALIFYING 13 19.3 QUALIFYING SCORING 13 19.4 QUALIFYING JUDGING CRITERIA 14 19.5 FORCE MAJEURE 17 20. TANDEM BATTLES 17 20.1 ELIMINATION FORMAT 17 20.2 TANDEM JUDGING CRITERIA 17 20.3 INCOMPLETE TANDEM RUNS 18 20.4 PASSING 19 20.5 TANDEM INITIATION PROCEDURE 19 20.6 TANDEM COLLISIONS AND CONTACT 20 20.7 CAR SERVICE DURING TANDEM 21 20.8 TANDEM REPLAYS AND TELEMETRY 22 21. -

Extreme Screw-Ups in Extreme Sports DR

Extreme Screw-ups in Extreme Sports DR. ERIC STANLEY, EMERGENCY PHYSICIAN, OMD, SLACKER. Welcome Who Am I? Eric Stanley ◦ Emergency Physician with Carilion Clinic ◦ OMD for several agencies in my region ◦ A squirrel who can’s stay away…. Me… I started running rescue in 1996 with AVRS Joined BVRS in 1998 Worked for Amherst County as paid staff in 2003 About Me I was this guy… Disclaimer I have a potty mouth. My jokes are not funny. This lecture is not for the squeamish. Objectives This is a trauma lecture. ◦ So you should learn some trauma care today. This is also about extreme sports. ◦ You should become more familiar with them. ◦ You should learn about some common injury patterns in them. This is “edutainment”. ◦ You should not get bored. ◦ If you do, send hate mail to Gary Brown and Tim Perkins at [email protected] and [email protected] What are Extreme Sports? Well, it is not this What are Extreme Sports? But this is about right….. So, what happens when it goes to shit? Parachutes History: ◦ First reference is from China in the 1100s. ◦ Around 1495, Leonardo DaVinci designed a pyramid-shaped, wooden framed parachute. ◦ Sport parachuting really began in 1950’s after WWII, when gear was abundant. Parachutes Modern day sport parachuting has evolved into two categories: 1. Skydiving ◦ Jumps made from aircraft using a main and reserve canopy. ◦ Opening altitude is at or above 2500 feet. 2. BASE jumping ◦ Jumps are made on a single canopy system. ◦ Opening altitude is best performed before impact. -

Journal of Asia Cross Country Rally

KYB TECHNICAL REVIEW No. 56 APR. 2018 Introduction Journal of Asia Cross Country Rally TANAKA Kazuhiro 1 Introduction attack racing. To compare, this would be like driving from Tokyo to Nagoya on general roads in a day of which the The Asia Cross Country Rally (hereinafter "AXCR") is section between Kanagawa and Shizuoka Prefectures is a South East Asia's largest four-/two-wheel rally raid race competition. certified by the International Automobile Federation (FIA) and the International Motorcycling Federation (FIM). Starting from the Kingdom of Thailand, partici- pants drive through its neighboring countries. The 2017 AXCR marked 22 years of history. This is a formal inter- national competition of this kind that is geographically closest to Japan and can be expected for the country to deliver a tremendous advertisement effect in the Asian region. Many Japanese teams with business strategies enter the rally, including those based on Japanese automo- bile manufacturers or four-wheel drive (4WD) vehicle related companies. Particularly in recent years, AXCR has seen a fierce battle for championships by international cars for emerging countries manufactured by various Photo 1 Bad road surface due to rainfall automobile makers. The participating teams have substan- tially raised their racing level in their rally vehicles with dramatically improved performance. From Japan, a lot of private teams also participate in the rally probably because 2 Position of Cross Country Rallies AXCR takes place during the summer holiday season in Japan and the costs incurred for participation is reason- Motorsports of four-wheel cars can be roughly classi- able. fied into three types: racing, rallying and trials. -

News Story Summary Alain Robert, a Free Climber Who Has Scaled Some

Session 2: God Judges Suggested Week of Use: December 8, 2019 Core Passage: Numbers 14:5-29 News Story Summary Alain Robert, a free climber who has scaled some of the world’s tallest buildings, is also known as the French Spider Man. His most recent feat was climbing the 502-foot Skyper building in Frankfurt, Germany in late September. He climbed it in around 20 minutes and did so without ropes or other safety equipment. He has also climbed to the top of the 68-floor Cheung Kong Center in Hong Kong, the Empire State Building in New York City, and the Eiffel Tower in Paris, often without safety harnesses. He has been arrested on multiple occasions for his unauthorized climbs. (For more on this story, search the Internet using the term “French Spider Man arrested in Germany”.) Focus Attention Prior to the group time, tape a large sheet of paper to a wall and write at the top, The Riskiest Thing I’ve Ever Done. As the group arrives, distribute markers and direct them to write on the paper the riskiest feat they have ever attempted (rock climbing, bungee jumping, skiing, etc.). Review their answers and lead the group to decide who the biggest risk taker in your group is. Tell the story of Alain Robert, the French Spider Man, who climbed the skyscraper in Germany without safety gear. Ask: How do the risks you’ve taken compare to Alain’s? Why do you think he takes such risks with his life? What makes a risk worth taking? Explain that today’s session focuses on an Old Testament story in which God’s people refused to take a risk—to trust God and His promises—and they suffered the consequences. -

A Climber's Guide to Townsville and Magnetic Island

Contents: Mt Stuart Castle Hill Minor Crags: West End Quarry Lazy Afternoon Wall University Wall Kissing Point Magnetic Island Front Cover: Curlew (23), Rocky Bay, Magnetic Island. Inside Front: Mt Stuart at dawn. Inside Back: Castle Hill at dawn. Back Cover: Physical Meditation(25), The Pinnacle, Mt Stuart. All photos by me unless acknowledged. Thanks to: everyone I’ve climbed with, especially Steve Baskerville and Jason Shaw for going to many of the minor crags with me; Scott Johnson for sending me a copy of his guide and other information; Lee Skidmore, Mark Gommers and Anthony Timms for going through drafts; Lee for letting me use slides and information from his Website; Andrew and Deb Thorogood for being very amenable employers and for letting me use their computer; Aussie Photographics whose cheap developing I recommend; Simon Thorogood for scanning the slides; the Army for letting us climb at Mt Stuart; the Rocks for being there and Tash for buying a computer and being lovely. Dedicated to Jason Shaw. Contact me at [email protected]. 1 Disclaimer Many of the climbs in this book have had few ascents. Rockclimbing is hazardous. The author accepts no responsibility for any inaccurate or incomplete information, nor for any controversial grading of climbs or dependance on fixed protection, some of which may be unreliable. This guide also assumes that users have a high level of ability, have received training from a skilled rockclimbing instructor, will use appropriate equipment properly and have care for personal safety. Also it should be obvious that large amounts of this publication are my opinion.