A Sense of Completeness, of Understanding, Enfolding All Difference”: 1 1 the Author Would Like to an Interview with Maggie Gee Thank the European Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diasporic Experience in the Novels of Indian Diaspora

International Journal of Scientific & Innovative Research Studies ISSN : 2347-7660 (Print) | ISSN : 2454-1818 (Online) The Quest for Roots : Diasporic Experience in the Novels of Indian Diaspora ARUN GULERIA VALLABH GOVT. COLLEGE, MANDI In the modern scenario, ‘diaspora’ is viewed as a experience. If a person has no home then there is term carrying many interpretations. The diasporic no question of his being alienated anywhere. It is experience today projects an experience of many in the home where a person’s roots are fixed and a overlapping. When we talk of the diasporas as person without a home has no place to live in and being transnationals it implies the multiple has no survival with true existence. Migrated and geographical spaces inhabited by them. People dispersed people not only experience their living outside their homelands in some way try and physical journey but have sweet and bitter effect maintain a connection with their homeland on their psyche with the sense of retrieving through history, culture and tradition that that memories of their original home. they religiously edify in their host lands. They look Life is said to be an endless journey, and back from the outside, not letting go off the \’home, it has been said, is not necessarily where baggage that they carried when they first left their one belongs but the place where one starts from.” native shores. The diasporic view their hostland or In The New Parochialism: Homeland in the writing adopted land as a temporary stopover destination of Indian Diaspora Jasbir jain avers that “the word and hence are not able to establish and emotional ‘Home’ no longer signifies a ‘given’, it does not bonding with the new land. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Race, Gender and Class in the Inheritance of Loss and Brick Lane

Race, Gender and Class in The Inheritance of Loss and Brick Lane A comparative study by Sissel Marie Lone A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages The University of Oslo In partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Master of Arts Degree Spring Term 2008 Contents Introduction 2 Chapter 1: The Theme of Race 12 1.1 The Theme of Race in The Inheritance of Loss 12 1.2 A Comparison of the Theme of Race in The Inheritance of Loss and Brick Lane 25 1.3 Concluding Remarks 33 Chapter 2: The Theme of Gender 35 2.1 The Theme of Gender in Brick Lane 35 2.2 A Comparison of the Theme of Gender in The Inheritance of Loss and Brick Lane 49 2.3 Concluding Remarks 58 Chapter 3: The Theme of Class 61 3.1 Introductory Remarks 61 3.2 A Comparison of the Theme of Class in The Inheritance of Loss and Brick Lane 64 3.3 Concluding Remarks 79 Conclusion 82 Bibliography 85 1 Introduction This thesis will discuss and compare the themes of race, gender and class in Brick Lane by Monica Ali and The Inheritance of Loss by Kiran Desai1. My main objective is to explore similarities and differences between the three themes, based on a thorough analysis of characters, settings and plots, and to find out how they correspond and how they differ. The themes of race, gender and class will be seen through the lens of migration and multiculturalism in a postcolonial setting, which is a prevailing theme in the two novels. -

'I Am Envious of Writers Who Are in India': Kiran Desai

“I am envious of writers who are in India”: Kiran Desai, the Man Booker Prize, and Indian Diasporic Writing Somdatta Mandal I: The Man Booker Prize: On the 10th of October 2006, defeating the five other novelists who made it to the short list, Kiran Desai won the UK’s leading literary award, the Man Booker Prize, for her novel, The Inheritance of Loss. Apart from being the youngest woman writer to receive this prize, she is the third writer of Indian origin – after Salman Rushdie and Arundhati Roy-- to win this prestigious award and also simultaneously catapult Indian writing in English to further worldwide fame as a special genre of writing. It is ironic that a book titled The Inheritance of Loss earned her 50,000 pound sterling and became a sort of redemption for the Desais, whom Salman Rushdie calls the “first dynasty of modern Indian fiction.” Although her mother Anita Desai had been short-listed for the Booker prize thrice -- Clear Light of Day (1980), In Custody (1984), and Fasting, Feasting (1999), with the prize then simply called the Booker and not the Man Booker as it is being called since 2002, she failed to receive the prize. It is further ironical that Inheritance, Kiran Desai’s second novel, was according to the author herself, much harder to write than her debut novel Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard, taking "seven years of my being determinedly isolated." It almost didn't get published in England. "The British said it didn't work,” she admitted, and nearly ten publishing houses rejected it until Hamish Hamilton bought it. -

The Postmodern Ideology and Maggie Gee's Fiction 26-68 II.1

POSTMODERNIST INTERPRETATIONS OF THE NOVELS OF MAGGIE GEE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO BHARATI VIDYAPEETH DEEMED UNIVERSITY, PUNE (UNDER: THE FACULTY OF ARTS, SOCIAL SCIENCES AND COMMERCE) FOR THE AWARD OF DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH BY MR. VAIBHAV A. DHAMAL M.A. UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. RAJARAM S. ZIRANGE M.A., M.Phil., Ph.D. RESEARCH CENTRE: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BHARATI VIDYAPEETH DEEMED UNIVERSITY YASHWANTRAO MOHITE COLLEGE OF ARTS, SCIENCE & COMMERCE, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2016 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the work incorporated in the thesis entitled ‘Postmodernist Interpretations of the Novels of Maggie Gee’ submitted by Mr. Vaibhav A. Dhamal for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English under the Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences and Commerce of Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University, Pune, was carried out in the Department of English, Yashwantrao Mohite College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University, Pune, during the period from 2011 to 2016 under the guidance of Dr. R. S. Zirange. Date: /09/2016 ( Dr. K. D. Jadhav ) DECLARATION BY THE CANDIDATE I hereby declare that the thesis entitled ‘Postmodernist Interpretations of the Novels of Maggie Gee’ submitted by me to the Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University, Pune for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in English under the Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences and Commerce is an original piece of work carried out by me under the supervision of Dr. Rajaram S. Zirange. I further declare that it has not been submitted to this or any other university or institution for the award of any Degree or Diploma. -

Magic Realism in Kiran Desai's Novel “Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard”

Vol. 5(3), pp. 79-81, May, 2014 DOI: 10.5897/IJEL2014.0572 International Journal of English and Literature ISSN 2141-2626 Copyright © 2014 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJEL Short Communication Magic realism in Kiran Desai’s novel “Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard” Ritu Sharma Department of Humanities, Jayoti Vidyapeeth Women’s University, Jaipur. India. Received 17 February 2014; Accepted 9 April 2014 Kiran Desai was born in 1971 and educated in India, England and the United States. She studied creative writing at Columbia University, where she was the recipient of a Woolrich fellowship. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker and Salman Rushdie's anthology Mirrorwork: Fifty years of Indian Writing. In 2006 Desai won the MAN Booker Prize for her novel The Inheritance of Loss. Kiran Desai depicts the contemporary society in terms of psychological and social realism with about to happen fact. Kiran Desai’s debut novel Hullaballoo in the Guava Orchard is based on magical realism. Kiran Desai is the daughter of Anita Desai, herself short-listed for the booker prize on three occasions. She was born in Chandigarh, and spent the early years of her life in Pune and Mumbai. She studied in the Cathedral and John Connon school. She left India at 14, and she and her mother then lived in England for a year, and then moved to the United States, where she studied creative writing at bennington college, hollins university and columbia university. Desai resides in the United States, where she is a permanent resident. -

Graduate Student Handbook Online Master of Arts in English

Graduate Student Handbook Online Master of Arts in English Revised Spring 2019 Contents I. Objectives of the Graduate Program in English ...................................................................... 3 II. The UNO Catalog and English Graduate Handbook .............................................................. 3 III. Advising: The Graduate Coordinator ................................................................................... 3 IV. Other Specifics Concerning the Online Master of Arts in English ...................................... 4 A. Course Requirements--General .............................................................................................. 4 B. Concentrations. ....................................................................................................................... 5 C. Electives ................................................................................................................................. 5 D. Graduate Courses in Other Fields .......................................................................................... 5 E. Transfer Credit ........................................................................................................................ 5 F. The Written Comprehensive Examination .............................................................................. 5 G. Thesis Option ......................................................................................................................... 6 H. Miscellaneous........................................................................................................................ -

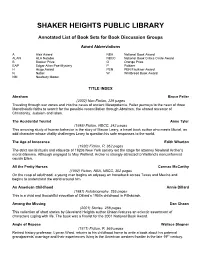

An Annotated Listing of Book Sets

SHAKER HEIGHTS PUBLIC LIBRARY Annotated List of Book Sets for Book Discussion Groups Award Abbreviations A Alex Award NBA National Book Award ALAN ALA Notable NBCC National Book Critics Circle Award B Booker Prize O Orange Prize EAP Edgar Allan Poe-Mystery P Pulitzer H Hugo Award PEN PEN/Faulkner Award N Nobel W Whitbread Book Award NM Newbery Medal TITLE INDEX Abraham Bruce Feiler (2002) Non-Fiction, 229 pages Traveling through war zones and into the caves of ancient Mesopotamia, Feiler journeys to the heart of three Monotheistic faiths to search for the possible reconciliation through Abraham, the shared ancestor of Christianity, Judaism and Islam. The Accidental Tourist Anne Tyler (1985) Fiction, NBCC, 342 pages This amusing study of human behavior is the story of Macon Leary, a travel book author who meets Muriel, an odd character whose vitality challenges Leary to question his safe responses to the world. The Age of Innocence Edith Wharton (1920) Fiction, P, 362 pages The strict social rituals and etiquette of 1920s New York society set the stage for attorney Newland Archer’s moral dilemma. Although engaged to May Welland, Archer is strongly attracted to Welland’s nonconformist cousin Ellen. All the Pretty Horses Cormac McCarthy (1992) Fiction, NBA, NBCC, 302 pages On the cusp of adulthood, a young man begins an odyssey on horseback across Texas and Mexico and begins to understand the world around him. An American Childhood Annie Dillard (1987) Autobiography, 255 pages This is a vivid and thoughtful evocation of Dillard’s 1950s childhood in Pittsburgh. Among the Missing Dan Chaon (2001) Stories, 258 pages This collection of short stories by Cleveland Heights author Chaon features an eclectic assortment of characters coping with life. -

A STUDY on WORKING STYLE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN RUTH JHABVALA and ANITA DESAI *Rashmi Malik **Dr

Globus An International Journal of Management & IT A Refereed Research Journal Vol 9 / No 2 / Jan-Jun 2018 ISSN: 0975-721X A STUDY ON WORKING STYLE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN RUTH JHABVALA AND ANITA DESAI *Rashmi Malik **Dr. M.S. Mishra Abstract Intro du ction In this context frequent movement between The paper discusses about that the novels of countries has become so common that, Anita Desai and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala have multiculturalism has turned inevitable. Further, this many hidden themes in them. The novels are researcher has felt that the fashionable multicultural often read and re-read, whenever with different context, has paved the way for cultural conflicts in viewpoints to unravel the knitted themes, to a method or the opposite. Thus, this researcher has explore more to the literary world especially and tried to seek out opposite. The multicultural to the society generally. The novels open many conflicts, its causes and therefore the consequences vistas to the literary critics. The researcher has with special regard to the novels of Anita Desai and attempted to explore a number of the aspects of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. The term ‘multiculturalism’ the novels of Anita Desai and Ruth Prawer and therefore the ‘multicultural conflicts’ are very Jhabvala i.e., the theme of multiculturalism and relevant to this age. During this light this researcher multicultural conflicts. Twentieth century and has haunted the subject, “Multicultural conflicts twenty first century are referred to as the age of within the novels of Anita Desai and Ruth Prawer globalization and liberalization. Jhabvala”. Keywords: Ruth Jhabvala, Anita Desai, Women, Working Style. -

The History of British Women's Writing General Editors: Jennie Batchelor

The History of British Women’s Writing General Editors: Jennie Batchelor and Cora Kaplan Advisory Board: Isobel Armstrong, Rachel Bowlby, Helen Carr, Carolyn Dinshaw, Margaret Ezell, Margaret Ferguson, Isobel Grundy, and Felicity Nussbaum The History of British Women’s Writing is an innovative and ambitious monograph series that seeks both to synthesise the work of several generations of feminist schol- ars, and to advance new directions for the study of women’s writing. Volume editors and contributors are leading scholars whose work collectively refl ects the global excellence in this expanding fi eld of study. It is envisaged that this series will be a key resource for specialist and non- specialist scholars and students alike. Titles include: Liz Herbert McAvoy and Diane Watt (editors) THE HISTORY OF BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING, 700– 1500 Volume One Caroline Bicks and Jennifer Summit (editors) THE HISTORY OF BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING, 1500– 1610 Volume Two Mihoko Suzuki (editor) THE HISTORY OF BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING, 1610– 1690 Volume Three Ros Ballaster (editor) THE HISTORY OF BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING, 1690– 1750 Volume Four Jacqueline M. Labbe (editor) THE HISTORY OF BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING, 1750– 1830 Volume Five Mary Joannou (editor) THE HISTORY OF BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING, 1920– 1945 Volume Eight The History of British Women’s Writing Series Standing Order ISBN 978– 0– 230– 20079– 1 hardback (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. Please contact your bookseller or, in case of diffi culty, write to us at the address below with your name and address, the title of the series and the ISBN quoted above. -

National Identity and Cultural Representation in the Novels of Arundhati Roy and Kiran Desai

National Identity and Cultural Representation in the Novels of Arundhati Roy and Kiran Desai National Identity and Cultural Representation in the Novels of Arundhati Roy and Kiran Desai By Sonali Das National Identity and Cultural Representation in the Novels of Arundhati Roy and Kiran Desai By Sonali Das This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Sonali Das All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0404-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0404-2 Dedicated to my Parents for their immense love & support The loss of national identity is the greatest defeat a nation can know, and it is inevitable under the contemporary form of colonization. —Slobodan Milosevic CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Acknowledgements .................................................................................... xi Chapter I ...................................................................................................... 1 Narrating a Nation and Defining National Identity Chapter II .................................................................................................. -

Award Winning Books

More Man Booker winners: 1995: Sabbath’s Theater by Philip Roth Man Booker Prize 1990: Possession by A. S. Byatt 1994: A Frolic of His Own 1989: Remains of the Day by William Gaddis 2017: Lincoln in the Bardo by Kazuo Ishiguro 1993: The Shipping News by Annie Proulx by George Saunders 1985: The Bone People by Keri Hulme 1992: All the Pretty Horses 2016: The Sellout by Paul Beatty 1984: Hotel du Lac by Anita Brookner by Cormac McCarthy 2015: A Brief History of Seven Killings 1982: Schindler’s List by Thomas Keneally 1991: Mating by Norman Rush by Marlon James 1981: Midnight’s Children 1990: Middle Passage by Charles Johnson 2014: The Narrow Road to the Deep by Salman Rushdie More National Book winners: North by Richard Flanagan 1985: White Noise by Don DeLillo 2013: Luminaries by Eleanor Catton 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2012: Bring Up the Bodies by Hilary Mantel 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike 2011: The Sense of an Ending National Book Award 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron by Julian Barnes 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 2010: The Finkler Question 2016: Underground Railroad by Howard Jacobson by Colson Whitehead 2009: Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 2008: The White Tiger by Aravind Adiga 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay 2007: The Gathering by Anne Enright 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride National Book Critics 2006: The Inheritance of Loss 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich by Kiran Desai 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward Circle Award 2005: The Sea by John Banville 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon 2004: The Line of Beauty 2009: Let the Great World Spin 2016: LaRose by Louise Erdrich by Alan Hollinghurst by Colum McCann 2015: The Sellout by Paul Beatty 2003: Vernon God Little by D.B.C.