Race, Gender and Class in the Inheritance of Loss and Brick Lane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Impact on the Inheritance of Loss by Kiran Desai

Conference Proceeding Issue Published in International Journal of Trend in Research and Development (IJTRD), ISSN: 2394-9333, www.ijtrd.com Cultural Impact on the Inheritance of Loss by Kiran Desai A. S. Artheeswari, M.Phil English, Arignar Anna Government Arts College, Villupuram, Tamilnadu, India Abstract: Kiran Desai is one of the talented and ambitious II. THE INHERITANCE OF LOSS younger Indian diasporic writers who have a significant role in The novel “The Inheritance of Loss” is an authentic study of Portraying and reflecting the difficulties and complexities of human relationship bedevilled by exile and cultural the experiences of the immigrants in literature. She belongs to encounters. Those human beings who are not enjoying their the second generation of indian diaspora. Her own experiences life seem to adhere to their cultural instinct and they detached of living in India, England and USA as well as her complicated from their real nature. This made a negative impact in their educational background in these three countries brand her not whole life and leads to cultural deformity when these people only as a distinctive and typical Diasporic writer, but also as a happened to live in a new world; they have to construct their product of multiculturalism. Kiran Desai , the winner of the own world based on their acquired culture and civilization. prestigious Man Booker Prize 2006 for her second novel “ THE INHERITANCE OF LOSS (2005 ) Created literary The novel brought her come to literary attention , winning the history by becoming the youngest ever woman to win the Betty Task Award .Desai‟s second novel The inheritance of prestigious prize at the age of 35. -

A Study of the Inheritance of Loss and Half a Life

Orientalising the Postcolonial Nation-State: A Study of The Inheritance of Loss and Half a Life A Dissertation Submitted to the Central University of Punjab For the Award of Master of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Manpreet Kaur Administrative Guide: Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana Dissertation Coordinator: Dr. Zameerpal Kaur Centre for Comparative Literature School of Languages, Literature and Culture Central University of Punjab, Bathinda August, 2012 CERTIFICATE I declare that the dissertation entitled “Orientalising the Postcolonial Nation-State: A Study of The Inheritance of Loss and Half a Life,” has been prepared by me under the guidance of Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana, and Dr. Zameerpal Kaur, Assistant Professor, Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab. No part of this dissertation has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. (Manpreet Kaur) Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. Date: ii Acknowledgement It is a pleasure to thank God, for making me able to achieve what I am today. I want to express my thanks to God, my parents and my family members. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the stalwart of my department my supervisor and Professor. P. S. Ramana, Dean, School of Languages, Literature and Culture and my dissertation Coordinator Dr. Zameerpal Kaur, Assistant Professor, Centre for Comparative Literature for their ingenuous guidance. I want to express my thanks to Dr. Amandeep Singh, Assistant Professor, Centre for Comparative Literature for his continuous and extremely useful assistance. -

Diasporic Experience in the Novels of Indian Diaspora

International Journal of Scientific & Innovative Research Studies ISSN : 2347-7660 (Print) | ISSN : 2454-1818 (Online) The Quest for Roots : Diasporic Experience in the Novels of Indian Diaspora ARUN GULERIA VALLABH GOVT. COLLEGE, MANDI In the modern scenario, ‘diaspora’ is viewed as a experience. If a person has no home then there is term carrying many interpretations. The diasporic no question of his being alienated anywhere. It is experience today projects an experience of many in the home where a person’s roots are fixed and a overlapping. When we talk of the diasporas as person without a home has no place to live in and being transnationals it implies the multiple has no survival with true existence. Migrated and geographical spaces inhabited by them. People dispersed people not only experience their living outside their homelands in some way try and physical journey but have sweet and bitter effect maintain a connection with their homeland on their psyche with the sense of retrieving through history, culture and tradition that that memories of their original home. they religiously edify in their host lands. They look Life is said to be an endless journey, and back from the outside, not letting go off the \’home, it has been said, is not necessarily where baggage that they carried when they first left their one belongs but the place where one starts from.” native shores. The diasporic view their hostland or In The New Parochialism: Homeland in the writing adopted land as a temporary stopover destination of Indian Diaspora Jasbir jain avers that “the word and hence are not able to establish and emotional ‘Home’ no longer signifies a ‘given’, it does not bonding with the new land. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

MIGRATION, GLOBALIZATION, and DIVIDED IDENTITY in KIRAN DESAI’S the INHERITANCE of LOSS Accepted: 2 Feb 2018 UDK: 821.111.09-31Desai, K

“Umjetnost riječi” LXII (2018) • 1 • Zagreb • January – June RESEARCH PAPER Ksenija K O N D A L I (University of Sarajevo) [email protected] MIGRATION, GLOBALIZATION, AND DIVIDED IDENTITY IN KIRAN DESAI’S THE INHERITANCE OF LOSS Accepted: 2 Feb 2018 UDK: 821.111.09-31Desai, K. 82:314.15:325.36 In this time of ever-accelerating migration and cultural globalization, the production of Anglophone literature and the field of literary studies reflect the profound influence of these processes. Among the group of transnational and multicultural authors who write literary texts that address these processes is Kiran Desai, whose personal background and literary output exemplify the growing presence and importance of transnational writing. Drawing on the studies of Vijay Mishra and Paul 101 Jay about diaspora and globalization, this paper discusses Kiran Desai’s novel The Inheritance of Loss (2006) in light of the colonial legacy of displacement and the resultant divided identity. Through an examination of the novel’s main themes centered on the impact of the U.S. capitalist empire and English colonization in India, this analysis explores the fragmentation of values and the crisis of individual and collective identity in an ever-changing, globalizing world. Spanning continents, and switching back and forth in time and viewpoints, Desai’s narrative reveals the ambivalence of the characters’ adjustment to the inexorable economic and social demands that leave them trapped between tradition and transition, colonialism and nationalism, diaspora and cosmopolitanism. This paper argues that the complex interplay of local custom, migration, postcolonial conflicts and diasporic existence both bring together and separate seemingly disparate worlds and characters. -

'I Am Envious of Writers Who Are in India': Kiran Desai

“I am envious of writers who are in India”: Kiran Desai, the Man Booker Prize, and Indian Diasporic Writing Somdatta Mandal I: The Man Booker Prize: On the 10th of October 2006, defeating the five other novelists who made it to the short list, Kiran Desai won the UK’s leading literary award, the Man Booker Prize, for her novel, The Inheritance of Loss. Apart from being the youngest woman writer to receive this prize, she is the third writer of Indian origin – after Salman Rushdie and Arundhati Roy-- to win this prestigious award and also simultaneously catapult Indian writing in English to further worldwide fame as a special genre of writing. It is ironic that a book titled The Inheritance of Loss earned her 50,000 pound sterling and became a sort of redemption for the Desais, whom Salman Rushdie calls the “first dynasty of modern Indian fiction.” Although her mother Anita Desai had been short-listed for the Booker prize thrice -- Clear Light of Day (1980), In Custody (1984), and Fasting, Feasting (1999), with the prize then simply called the Booker and not the Man Booker as it is being called since 2002, she failed to receive the prize. It is further ironical that Inheritance, Kiran Desai’s second novel, was according to the author herself, much harder to write than her debut novel Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard, taking "seven years of my being determinedly isolated." It almost didn't get published in England. "The British said it didn't work,” she admitted, and nearly ten publishing houses rejected it until Hamish Hamilton bought it. -

9 Shades of Fiction Good Reads Authors

Classics Prizewinner Your Choice Be adventurous and delve into 19th Century Man Booker books from other genres Jane Austen Pat Barker Chimamanda Adichie Listed are a selection of authors in each genre. 1775 - 1817 1995 Kate Atkinson The Ghost Road Use in the Author search to browse their titles Alexandre Dumas Margaret Atwood www.whangarei-libraries.com 1802 - 1870 Julian Barnes in the Library Catalogue Elizabeth Gaskell 2011 William Boyd 1810 - 1865 The Sense of an Ending T C Boyle New Zealand Crime or William Makepeace Kiran Desai Geraldine Brooks Fiction Romance Mystery Sci Fi Horror Sea Story Thackeray 2006 1811 - 1863 The Inheritance of Loss A S Byatt Peter Carey Alix Bosco Mary Balogh Nicholas Blake Douglas Adams L A Banks Broos Campbell Charles Dickens Thomas Keneally 1812 - 1870 1982 Justin Cartwright Deborah Challinor Suzanne Brockmann James Lee Burke Catherine Asaro Chaz Brenchley Clive Cussler Anthony Trollope Schindler’s Ark Louis De Bernières Barry Crump Christine Feehan Lee Child Isaac Asimov Poppy Z Brite David Donachie 1815 - 1882 Hilary Mantel Emma Donoghue Robyn Donald Julie Garwood Agatha Christie Ben Bova Clive Barker C S Forester Charlotte Bronte 2009 Jeffrey Eugenides Fiona Farrell Georgette Heyer Harlan Coben Ray Bradbury Ramsey Campbell Alexander Fullerton 1816 -1855 Wolf Hall Fyodor Dostoevsky Margaret Forster Laurence Fearnley Sherrilyn Kenyon Michael Connelly Orson Scott Card Francis Cottam Seth Hunter Yann Martel 1821 - 1881 2002 Amitav Ghosh Janet Frame Lisa Kleypas Colin Cotterill C J Cherryh Justin Cronin -

Golden Man Booker Prize Shortlist Celebrating Five Decades of the Finest Fiction

Press release Under embargo until 6.30pm, Saturday 26 May 2018 Golden Man Booker Prize shortlist Celebrating five decades of the finest fiction www.themanbookerprize.com| #ManBooker50 The shortlist for the Golden Man Booker Prize was announced today (Saturday 26 May) during a reception at the Hay Festival. This special one-off award for Man Booker Prize’s 50th anniversary celebrations will crown the best work of fiction from the last five decades of the prize. All 51 previous winners were considered by a panel of five specially appointed judges, each of whom was asked to read the winning novels from one decade of the prize’s history. We can now reveal that that the ‘Golden Five’ – the books thought to have best stood the test of time – are: In a Free State by V. S. Naipaul; Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively; The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje; Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel; and Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders. Judge Year Title Author Country Publisher of win Robert 1971 In a Free V. S. Naipaul UK Picador McCrum State Lemn Sissay 1987 Moon Penelope Lively UK Penguin Tiger Kamila 1992 The Michael Canada Bloomsbury Shamsie English Ondaatje Patient Simon Mayo 2009 Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel UK Fourth Estate Hollie 2017 Lincoln George USA Bloomsbury McNish in the Saunders Bardo Key dates 26 May to 25 June Readers are now invited to have their say on which book is their favourite from this shortlist. The month-long public vote on the Man Booker Prize website will close on 25 June. -

BOOKERJEVA NAGRADA (Man Booker Prize) Je Nagrada Za

BOOKERJEVA NAGRADA (Man Booker Prize) Je nagrada za najboljši roman v angleškem jeziku, ki ga je napisal avtor iz Commonwealtha ali Irske, podeljuje jo Booker Prize Foundation od leta 1969. In velja za eno najuglednejših književnih nagrad v angleško govorečem svetu. Nagrajene knjige, ki jih imamo v naši knjižnični zbirki, so označene debelejše: 2020 Douglas Stuart: SHUGGIE BAIN 2019 Margaret Atwood: TESTAMENTI in Bernardine Evaristo: GIRL, WOMAN, OTHER 2018 Anna Burns: MILKMAN 2017 Geroge Saunders: LINCOLN IN THE BARDO 2016 Paul Beatty: THE SELLOUT 2015 Marlon James: A BRIEF HISTORY OF SEVEN KILLINGS 2014 Richard Flanagan: THE NARROW ROAD TO THE DEEP NORTH (Ozka pot globoko do severa, 2017) 2013 Eleanor Catton: THE LUMINARIES 2012 Hilary Mantel: BRING UP THE BODIES 2011 Julian Barnes: THE SENSE OF AN ENDING (Smisel konca, 2012) 2010 Howard Jacobson: THE FINKLER QUESTION (Finklersko vprašanje, 2012) 2009 Hilary Mantel: WOLF HALL 2008 Aravind Adiga: THE WHITE TIGER (Beli tiger, 2010; prev. Marko Trobevšek) 2007 Anne Enright: THE GATHERING (Shajanje, 2013) 2006 Kiran Desai: THE INHERITANCE OF LOSS (Dediščina izgube, 2007) 2005 John Banville: THE SEA (Morje, 2006) 2004 Alan Hollinghurst: THE LINE OF BEAUTY (Linija lepote, 2006) 2003 DBC Pierre: VERNON GOD LITTLE (Vernon Gospod Little, 2004) 2002 Yann Martel: LIFE OF PI (Pijevo življenje, 2004) 2001 Peter Carey: TRUE HISTORY OF THE KELLY GANG 2000 Margaret Atwood: THE BLIND ASSASSIN (Slepi morilec, 2010) 1999 J. M. Coetzee: DISGRACE (Sramota, 2004) 1998 Ian McEwan: AMSTERDAM (Amsterdam, 2004) 1997 Arundhati Roy: THE GOD OF SMALL THINGS (Bog majhnih stvari, 2000) 1996 Graham Swift: LAST ORDERS (Zadnja želja, 2007) 1995 Pat Barker: THE GHOST ROAD 1994 James Kelman: HOW LATE IT WAS, HOW LATE (Kako pozno, pozno je bilo, 2006) 1993 Roddy Doyle: PADDY CLARKE HA HA HA (1995) 1992 Michael Ondaatje: THE ENGLISH PATIENT (Angleški pacient, 1998) Barry Unsworth: SACRED HUNGER 1991 Ben Okri: THE FAMISHED ROAD (Cesta sestradanih, 2016) 1990 A. -

Magic Realism in Kiran Desai's Novel “Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard”

Vol. 5(3), pp. 79-81, May, 2014 DOI: 10.5897/IJEL2014.0572 International Journal of English and Literature ISSN 2141-2626 Copyright © 2014 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJEL Short Communication Magic realism in Kiran Desai’s novel “Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard” Ritu Sharma Department of Humanities, Jayoti Vidyapeeth Women’s University, Jaipur. India. Received 17 February 2014; Accepted 9 April 2014 Kiran Desai was born in 1971 and educated in India, England and the United States. She studied creative writing at Columbia University, where she was the recipient of a Woolrich fellowship. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker and Salman Rushdie's anthology Mirrorwork: Fifty years of Indian Writing. In 2006 Desai won the MAN Booker Prize for her novel The Inheritance of Loss. Kiran Desai depicts the contemporary society in terms of psychological and social realism with about to happen fact. Kiran Desai’s debut novel Hullaballoo in the Guava Orchard is based on magical realism. Kiran Desai is the daughter of Anita Desai, herself short-listed for the booker prize on three occasions. She was born in Chandigarh, and spent the early years of her life in Pune and Mumbai. She studied in the Cathedral and John Connon school. She left India at 14, and she and her mother then lived in England for a year, and then moved to the United States, where she studied creative writing at bennington college, hollins university and columbia university. Desai resides in the United States, where she is a permanent resident. -

Graduate Student Handbook Online Master of Arts in English

Graduate Student Handbook Online Master of Arts in English Revised Spring 2019 Contents I. Objectives of the Graduate Program in English ...................................................................... 3 II. The UNO Catalog and English Graduate Handbook .............................................................. 3 III. Advising: The Graduate Coordinator ................................................................................... 3 IV. Other Specifics Concerning the Online Master of Arts in English ...................................... 4 A. Course Requirements--General .............................................................................................. 4 B. Concentrations. ....................................................................................................................... 5 C. Electives ................................................................................................................................. 5 D. Graduate Courses in Other Fields .......................................................................................... 5 E. Transfer Credit ........................................................................................................................ 5 F. The Written Comprehensive Examination .............................................................................. 5 G. Thesis Option ......................................................................................................................... 6 H. Miscellaneous........................................................................................................................ -

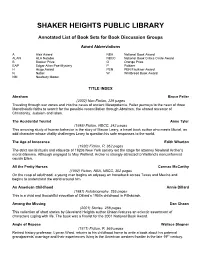

An Annotated Listing of Book Sets

SHAKER HEIGHTS PUBLIC LIBRARY Annotated List of Book Sets for Book Discussion Groups Award Abbreviations A Alex Award NBA National Book Award ALAN ALA Notable NBCC National Book Critics Circle Award B Booker Prize O Orange Prize EAP Edgar Allan Poe-Mystery P Pulitzer H Hugo Award PEN PEN/Faulkner Award N Nobel W Whitbread Book Award NM Newbery Medal TITLE INDEX Abraham Bruce Feiler (2002) Non-Fiction, 229 pages Traveling through war zones and into the caves of ancient Mesopotamia, Feiler journeys to the heart of three Monotheistic faiths to search for the possible reconciliation through Abraham, the shared ancestor of Christianity, Judaism and Islam. The Accidental Tourist Anne Tyler (1985) Fiction, NBCC, 342 pages This amusing study of human behavior is the story of Macon Leary, a travel book author who meets Muriel, an odd character whose vitality challenges Leary to question his safe responses to the world. The Age of Innocence Edith Wharton (1920) Fiction, P, 362 pages The strict social rituals and etiquette of 1920s New York society set the stage for attorney Newland Archer’s moral dilemma. Although engaged to May Welland, Archer is strongly attracted to Welland’s nonconformist cousin Ellen. All the Pretty Horses Cormac McCarthy (1992) Fiction, NBA, NBCC, 302 pages On the cusp of adulthood, a young man begins an odyssey on horseback across Texas and Mexico and begins to understand the world around him. An American Childhood Annie Dillard (1987) Autobiography, 255 pages This is a vivid and thoughtful evocation of Dillard’s 1950s childhood in Pittsburgh. Among the Missing Dan Chaon (2001) Stories, 258 pages This collection of short stories by Cleveland Heights author Chaon features an eclectic assortment of characters coping with life.