'I Am Envious of Writers Who Are in India': Kiran Desai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memories of Rain

Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh (Hum.), Vol. 60(1), 2015, pp. 17-34 TEXT WITHIN TEXT: THE SHAPING OF SUNETRA GUPTA’S MEMORIES OF RAIN ASM Maswood Akhter* Abstract Instead of venturing into the more expected readings of Sunetra Gupta’s debut novel Memories of Rain (1992) – which won her prestigious national literary award in India, the Sahitya Akademi Award for 1996 – as embodying the author’s intricate writing style or diasporic angst or desire of conveying her ideas and thought about Calcutta to a Western audience, this paper seeks to raise the issue of intertextuality in the novel. It shows how this novel is immersed in conversation with the expanse of literature produced in different periods and diverse cultural settings. Gupta’s extremely literary– even canonical– sensibility is revealed in the centrality and profusion of allusions and references that range from Euripides to Tagore. The paper argues that for a more nuanced understanding of Memories of Rain it is important to be aware of the influence and interplay of diverse texts providing the novel its context and meaning as well as shaping its narrative and characters. With all its lyrical evocation of the 1970s’ Calcutta1 and its haunting memories, Sunetra Gupta’s Memories of Rain (1992) remains rather a complex fictional narrative. Readers are at once intrigued by its sustained interior monologues, figurative language and sensuous poetic imagery, its warped chronology alternating flashbacks and fantasy with the present, or its linguistic experiments resulting in paragraph-stretched sentences conjoined by commas and overflowing grammatical halts. This paper, however, engages itself with a different issue: the importance and implications of the abundance of intertextual references and allusions in the novel.2 I aim to look into the overwhelming canonical shadows lurking through the text to argue that this eclectic range of allusions and literary * Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Rajshahi 1 Since 2001 Calcutta was transformed into Kolkata. -

Diasporic Experience in the Novels of Indian Diaspora

International Journal of Scientific & Innovative Research Studies ISSN : 2347-7660 (Print) | ISSN : 2454-1818 (Online) The Quest for Roots : Diasporic Experience in the Novels of Indian Diaspora ARUN GULERIA VALLABH GOVT. COLLEGE, MANDI In the modern scenario, ‘diaspora’ is viewed as a experience. If a person has no home then there is term carrying many interpretations. The diasporic no question of his being alienated anywhere. It is experience today projects an experience of many in the home where a person’s roots are fixed and a overlapping. When we talk of the diasporas as person without a home has no place to live in and being transnationals it implies the multiple has no survival with true existence. Migrated and geographical spaces inhabited by them. People dispersed people not only experience their living outside their homelands in some way try and physical journey but have sweet and bitter effect maintain a connection with their homeland on their psyche with the sense of retrieving through history, culture and tradition that that memories of their original home. they religiously edify in their host lands. They look Life is said to be an endless journey, and back from the outside, not letting go off the \’home, it has been said, is not necessarily where baggage that they carried when they first left their one belongs but the place where one starts from.” native shores. The diasporic view their hostland or In The New Parochialism: Homeland in the writing adopted land as a temporary stopover destination of Indian Diaspora Jasbir jain avers that “the word and hence are not able to establish and emotional ‘Home’ no longer signifies a ‘given’, it does not bonding with the new land. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Race, Gender and Class in the Inheritance of Loss and Brick Lane

Race, Gender and Class in The Inheritance of Loss and Brick Lane A comparative study by Sissel Marie Lone A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages The University of Oslo In partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Master of Arts Degree Spring Term 2008 Contents Introduction 2 Chapter 1: The Theme of Race 12 1.1 The Theme of Race in The Inheritance of Loss 12 1.2 A Comparison of the Theme of Race in The Inheritance of Loss and Brick Lane 25 1.3 Concluding Remarks 33 Chapter 2: The Theme of Gender 35 2.1 The Theme of Gender in Brick Lane 35 2.2 A Comparison of the Theme of Gender in The Inheritance of Loss and Brick Lane 49 2.3 Concluding Remarks 58 Chapter 3: The Theme of Class 61 3.1 Introductory Remarks 61 3.2 A Comparison of the Theme of Class in The Inheritance of Loss and Brick Lane 64 3.3 Concluding Remarks 79 Conclusion 82 Bibliography 85 1 Introduction This thesis will discuss and compare the themes of race, gender and class in Brick Lane by Monica Ali and The Inheritance of Loss by Kiran Desai1. My main objective is to explore similarities and differences between the three themes, based on a thorough analysis of characters, settings and plots, and to find out how they correspond and how they differ. The themes of race, gender and class will be seen through the lens of migration and multiculturalism in a postcolonial setting, which is a prevailing theme in the two novels. -

Women Novelists in Indian English Literature

WOMEN NOVELISTS IN INDIAN ENGLISH LITERATURE DR D. RAJANI DEIVASAHAYAM S. HIMA BINDU Associate Professor in English Assistant Professor in English Ch. S. D. St. Theresa’s Autonomous College Ch. S. D. St. Theresa’s Autonomous for Women College for Women Eluru, W.G. DT. (AP) INDIA Eluru, W.G. DT., (AP) INDIA Woman has been the focal point of the writers of all ages. On one hand, he glorifies and deifies woman, and on the other hand, he crushes her with an iron hand by presenting her in the image of Sita, the epitome of suffering. In the wake of the changes that have taken place in the society in the post-independence period, many novelists emerged on the scene projecting the multi-faceted aspects of woman. The voice of new Indian woman is heard from 1970s with the emergence of Indian English women novelists like Nayantara Sehgal, Anitha Desai, Kamala Markandaya, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, Arundhati Roy, Shashi Deshpande, Gita Mehta, Bharathi Mukherjee, and Jhumpha Lahiri.. These Feminist writers tried to stamp their authority in a male dominated environment as best as it is possible to them. This paper focuses on the way these women writers present the voice of the Indian woman who was hitherto suppressed by the patriarchal authority. Key words: suppression, identity, individuality, resistance, assertion. INTRODUCTION Indian writers have contributed much for the overall development of world literature with their powerful literary expression and immense depth in characterization. In providing global recognition to Indian writing in English, the novel plays a significant role as they portray the multi-faceted problems of Indian life and the reactions of common men and women in the society. -

Magic Realism in Kiran Desai's Novel “Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard”

Vol. 5(3), pp. 79-81, May, 2014 DOI: 10.5897/IJEL2014.0572 International Journal of English and Literature ISSN 2141-2626 Copyright © 2014 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJEL Short Communication Magic realism in Kiran Desai’s novel “Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard” Ritu Sharma Department of Humanities, Jayoti Vidyapeeth Women’s University, Jaipur. India. Received 17 February 2014; Accepted 9 April 2014 Kiran Desai was born in 1971 and educated in India, England and the United States. She studied creative writing at Columbia University, where she was the recipient of a Woolrich fellowship. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker and Salman Rushdie's anthology Mirrorwork: Fifty years of Indian Writing. In 2006 Desai won the MAN Booker Prize for her novel The Inheritance of Loss. Kiran Desai depicts the contemporary society in terms of psychological and social realism with about to happen fact. Kiran Desai’s debut novel Hullaballoo in the Guava Orchard is based on magical realism. Kiran Desai is the daughter of Anita Desai, herself short-listed for the booker prize on three occasions. She was born in Chandigarh, and spent the early years of her life in Pune and Mumbai. She studied in the Cathedral and John Connon school. She left India at 14, and she and her mother then lived in England for a year, and then moved to the United States, where she studied creative writing at bennington college, hollins university and columbia university. Desai resides in the United States, where she is a permanent resident. -

A Room of Their Own: Women Novelists 109

A Room of their Own: Women Novelists 109 4 A Room of their Own: Women Novelists There is a clear distinction between the fiction of the old masters and the new novel, with Rushdie's Midnight's Children providing a convenient watershed. When it comes to women novelists, the distinction is not so clear cut. The older generation of women writers (they are a generation younger than the "Big Three") have produced significant work in the nineteen-eighties: Anita Desai's and Nayantara Sahgal's best work appeared in this period. We also have the phenomenon of the "late bloomers": Shashi Deshpande (b. 1937) and Nisha da Cunha (b. 1940) have published their first novel and first collection of short stories in the eighties and nineties respectively. But the men and women writers also have much in common. Women too have written novels of Magic Realism, social realism and regional fiction, and benefited from the increasing attention (and money) that this fiction has received, there being an Arundhati Roy to compare with Vikram Seth in terms of royalties and media attention. In terms of numbers, less women writers have been published abroad; some of the best work has come from stay-at- home novelists like Shashi Deshpande. Older Novelists Kamala Markandaya has published just one novel after 1980. Pleasure City (1982) marks a new direction in her work. The cultural confrontation here is not the usual East verses West, it is tradition and modernity. An efficient multinational corporation comes to a sleepy fishing village on the Coromandal coast to built a holiday resort, Shalimar, the pleasure city; and the villagers, struggling at subsistence level, cannot resist the regular income offered by jobs in it. -

Graduate Student Handbook Online Master of Arts in English

Graduate Student Handbook Online Master of Arts in English Revised Spring 2019 Contents I. Objectives of the Graduate Program in English ...................................................................... 3 II. The UNO Catalog and English Graduate Handbook .............................................................. 3 III. Advising: The Graduate Coordinator ................................................................................... 3 IV. Other Specifics Concerning the Online Master of Arts in English ...................................... 4 A. Course Requirements--General .............................................................................................. 4 B. Concentrations. ....................................................................................................................... 5 C. Electives ................................................................................................................................. 5 D. Graduate Courses in Other Fields .......................................................................................... 5 E. Transfer Credit ........................................................................................................................ 5 F. The Written Comprehensive Examination .............................................................................. 5 G. Thesis Option ......................................................................................................................... 6 H. Miscellaneous........................................................................................................................ -

Playing Host to Evolution

books and arts Newton Morton’s rather sketchy chapter by expressions of embarrassment at the on genetic epidemiology provides a useful “Eskimo” custom of lending their wives to Playing host to comment on both its history and its meth- dinner guests (in the concluding chapter by odology, but might have more properly Luca Cavalli-Sforza), even if the reference is evolution belonged in the introduction. So too would to the Lonely Planet guidebooks. One can Infectious Disease and Michel Tibayrenc’s endorsement of the imagine such a gross example of the com- Host–Pathogen Evolution Human Genome Diversity Project as a means moditization of women appearing in one of edited by Krishna R. Dronamraju of answering certain critical questions sur- Haldane’s essays for the Daily Worker,but it is Cambridge University Press: 2004. 384 pp. rounding susceptibility to infectious disease. doubtful that it would have found its way to £65, $95 Finally, extending haldanesque thinking to the part of his mind that dwelt upon disease ■ Sunetra Gupta diseases of unknown origin, the chapter and host evolution. on diabetes by Kyle and Gregory Cochran is Sunetra Gupta is in the Department of Zoology, It is apt that in the year that marks the 40th a refreshing addition to a book that could University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK. anniversary of the death of J. B. S. Haldane, have restricted itself to diseases that are we should have a book on host–pathogen obviously infectious. evolution that so explicitly acknowledges But set among these are several chapters the debt this field owes to him. -

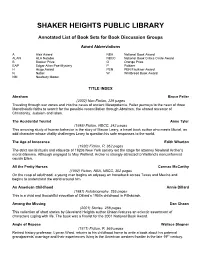

An Annotated Listing of Book Sets

SHAKER HEIGHTS PUBLIC LIBRARY Annotated List of Book Sets for Book Discussion Groups Award Abbreviations A Alex Award NBA National Book Award ALAN ALA Notable NBCC National Book Critics Circle Award B Booker Prize O Orange Prize EAP Edgar Allan Poe-Mystery P Pulitzer H Hugo Award PEN PEN/Faulkner Award N Nobel W Whitbread Book Award NM Newbery Medal TITLE INDEX Abraham Bruce Feiler (2002) Non-Fiction, 229 pages Traveling through war zones and into the caves of ancient Mesopotamia, Feiler journeys to the heart of three Monotheistic faiths to search for the possible reconciliation through Abraham, the shared ancestor of Christianity, Judaism and Islam. The Accidental Tourist Anne Tyler (1985) Fiction, NBCC, 342 pages This amusing study of human behavior is the story of Macon Leary, a travel book author who meets Muriel, an odd character whose vitality challenges Leary to question his safe responses to the world. The Age of Innocence Edith Wharton (1920) Fiction, P, 362 pages The strict social rituals and etiquette of 1920s New York society set the stage for attorney Newland Archer’s moral dilemma. Although engaged to May Welland, Archer is strongly attracted to Welland’s nonconformist cousin Ellen. All the Pretty Horses Cormac McCarthy (1992) Fiction, NBA, NBCC, 302 pages On the cusp of adulthood, a young man begins an odyssey on horseback across Texas and Mexico and begins to understand the world around him. An American Childhood Annie Dillard (1987) Autobiography, 255 pages This is a vivid and thoughtful evocation of Dillard’s 1950s childhood in Pittsburgh. Among the Missing Dan Chaon (2001) Stories, 258 pages This collection of short stories by Cleveland Heights author Chaon features an eclectic assortment of characters coping with life. -

Between Diaspora and Transnationalism in Divakaruni’S the Mistress of Spices and Sunetra Gupta’S So Good in Black

ISSN 2249-4529 www.pintersociety.com GENERAL ISSUE VOL: 8, No.: 1, SPRING 2018 UGC APPROVED (Sr. No.41623) BLIND PEER REVIEWED About Us: http://pintersociety.com/about/ Editorial Board: http://pintersociety.com/editorial-board/ Submission Guidelines: http://pintersociety.com/submission-guidelines/ Call for Papers: http://pintersociety.com/call-for-papers/ All Open Access articles published by LLILJ are available online, with free access, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License as listed on http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Individual users are allowed non-commercial re-use, sharing and reproduction of the content in any medium, with proper citation of the original publication in LLILJ. For commercial re-use or republication permission, please contact [email protected] 98 | The Umbilical Cord ‘Home’: From ‘Roots’ to ‘Routes’ The Umbilical Cord ‘Home’: From ‘Roots’ to ‘Routes’ between Diaspora and Transnationalism in Divakaruni’s The Mistress of Spices and Sunetra Gupta’s So Good in Black Neelu Jain Abstract: The emerging interest in diaspora studies has recently begun to permeate various academic disciplines, thereby laying greater importance in recognizing and understanding diasporic communities as transnational organizations reflecting the theoretical shifts and current trends in migration. Although diaspora and transnationalism were quite different phenomena but with the advancement in the means of transport and communication, it has become easy for the diasporic community to connect with the people in homeland. Consequently, the diasporic gaze has shifted from identity crisis to identity formation to transnationalism and globalization due to which the notions of epicenter and boundary, home and exile are falling apart thereby giving a better understanding and importance of the word ‘diaspora’ in the current context. -

A STUDY on WORKING STYLE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN RUTH JHABVALA and ANITA DESAI *Rashmi Malik **Dr

Globus An International Journal of Management & IT A Refereed Research Journal Vol 9 / No 2 / Jan-Jun 2018 ISSN: 0975-721X A STUDY ON WORKING STYLE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN RUTH JHABVALA AND ANITA DESAI *Rashmi Malik **Dr. M.S. Mishra Abstract Intro du ction In this context frequent movement between The paper discusses about that the novels of countries has become so common that, Anita Desai and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala have multiculturalism has turned inevitable. Further, this many hidden themes in them. The novels are researcher has felt that the fashionable multicultural often read and re-read, whenever with different context, has paved the way for cultural conflicts in viewpoints to unravel the knitted themes, to a method or the opposite. Thus, this researcher has explore more to the literary world especially and tried to seek out opposite. The multicultural to the society generally. The novels open many conflicts, its causes and therefore the consequences vistas to the literary critics. The researcher has with special regard to the novels of Anita Desai and attempted to explore a number of the aspects of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. The term ‘multiculturalism’ the novels of Anita Desai and Ruth Prawer and therefore the ‘multicultural conflicts’ are very Jhabvala i.e., the theme of multiculturalism and relevant to this age. During this light this researcher multicultural conflicts. Twentieth century and has haunted the subject, “Multicultural conflicts twenty first century are referred to as the age of within the novels of Anita Desai and Ruth Prawer globalization and liberalization. Jhabvala”. Keywords: Ruth Jhabvala, Anita Desai, Women, Working Style.