Patterns and Links in Satyajit Ray's Fairytale Trilogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POWERFUL and POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS in SATYAJIT RAY's FILMS by DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Fi

POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS BY DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts ____________________ Chairperson Committee members* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* Date defended: ______________ The Thesis Committee of Deb Banerjee certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS Committee: ________________________________ Chairperson* _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Date approved:_______________________ ii CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….... 2 Chapter 1: Political Scenario of India and Bengal at the Time Periods of the Two Films’ Production……………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 2: Power of the Ruler/King……………………………………………….. 23 Chapter 3: Power of Class/Caste/Religion………………………………………… 31 Chapter 4: Power of Gender……………………………………………………….. 38 Chapter 5: Power of Knowledge and Technology…………………………………. 45 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………. 52 Work Cited………………………………………………………………………... 55 i Abstract Scholars have discussed Indian film director, Satyajit Ray’s films in a myriad of ways. However, there is paucity of literature that examines Ray’s two films, Goopy -

The Writing in Goopy Bagha

International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Right(ing) the Writing: An Exploration of Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne Amrita Basu Haldia Institute of Technology, Haldia, West Bengal, India Abstract The act of writing, owing to the permanence it craves, may be said to be in continuous interaction with the temporal flow of time. It continues to stimulate questions and open up avenues for discussion. Writing people, events and relationships into existence is a way of negotiating with the illusory. But writing falters. This paper attempts a reading of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne in terms of power politics through the lens of the manipulation of written codes and inscriptions in the film. Identities and cultures are constructed through inscriptions and writings. But in the wrong hands, this medium of communication which has the potential to bring people together may wreck havoc on the social and political system. Writing, or the misuse of it, in the case of the film, reveals the nature of reality as provisional. If writing gives a seal of authenticity to a message, it can also become the casualty of its own creation. Key words: Inscription, Power, Politics, Writing, Social system 1 International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Introduction Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne by Satyajit Ray is a fun film for children of all ages; it ran to packed houses in West Bengal for a record 51 weeks and is considered one of the most commercially successful Ray films. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora Rabindranath Tagore wrote a poem in the autograph book of young Satyajit whom he met in idyllic Shantiniketan. The poem, translated in English, reads: ‘Too long I’ve wandered from place to place/Seen mountains and seas at vast expense/Why haven’t I stepped two yards from my house/Opened my eyes and gazed very close/At a glistening drop of dew on a piece of paddy grain?’ Years later, Satyajit Ray the celebrated Renaissance Man, captured this beauty, which is just two steps away from our homes but which we fail to appreciate on our own in many of his masterpieces stunning the audience with his gritty, neo realistic films in which he wore several hats- writing all his screenplays with finely detailed sketches of shot sequences and experimenting in lighting, music, editing and incorporating unusual camera angles. Several of his films were based on his own stories and his appreciation of classical music is fairly apparent in his music compositions resulting in some rather distinctive signature Ray tunes collaborating with renowned classical musicians such as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar and Vilayat Khan. No surprises there. Born a hundred years ago in 1921 in an extraordinarily talented Bengali Brahmo family, Satyajit Ray carried forward his illustrious legacy with astonishing ease and finesse. Both his grandfather Upendra Kishore RayChaudhuri and his father Sukumar RayChaudhuri are extremely well known children’s writers. It is said that there is hardly any Bengali child who has not grown up listening to or reading Upendra Kishore’s stories about the feisty little bird Tuntuni or the musicians Goopy Gyne and Bagha Byne. -

Satyajit's Bhooter Raja

postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed ISSN: 2456-7507 postscriptum.co.in Volume II Number i (January 2017) Nag, Sourav K. “Decolonising the Eerie: ...” pp. 41-50 Decolonising the Eerie: Satyajit’s Bhooter Raja (the King of Ghosts) in Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) Sourav Kumar Nag Assistant Professor in English, Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya, Bankura The author is an assistant professor of English at Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya. He has published research articles in various national and international journals. His preferred literary areas include African literature, Literary Theory and Indian English Literature. At present, he is working on his PhD on Ngugi Wa Thiong’o. Abstract This paper is a critical investigation of the socio-political situation of the Indianised spectral king (Bhooter Raja) in Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) and also of Ray’s handling of the marginalised in the movie. The movie is read as an allegory of postcolonial struggle told from a regional perspective. Ray’s portrayal of the Bhooter Raja (The king of ghosts) is typically Indianised. He deliberately deviates from the colonial tradition of Gothic fiction and customised Upendrakishore’s tale as a postcolonial narrative. This paper focuses on Ray’s vision of regional postcolonialism. Keywords ghost, eerie, postcolonial, decolonisation, subaltern Nag, S. K. Decolonising the Eerie ... 42 I cannot help being nostalgic sitting on my desk to write on Satyajit Ray‟s adaptation of Goopy Gayne Bagha Bayne (1969). I remember how I gaped to watch the movie the first time on Doordarsan. Not being acquainted with Bhooter Raja (The king of ghosts) before, I got startled to see the shiny black shadow with flashing electric bulbs around and hearing his reverberated nasal chant of three blessings. -

Reality, Realism and Fantasy: a Study of Ray's Children's Fiction Hirak

Reality, Realism and Fantasy: A Study of Ray’s Children’s fiction Hirak Rajar Deshe Arpita Sarker Research Scholar (M.Phil.) University of Delhi India Abstract In my paper I intend to first explain different form of realism by discussing Ian Watt‟s definition of realism, in The Rise of The Novel comparing and contrasting it with Brecht and Luckas‟s idea of realism as explained in Bertolt Brecht: Against George Luckas. Secondly I will discuss in brief the difference between reality and realism in a work of fiction. Thirdly, I will talk about the portrayal of reality and realism in children‟s literature, using socialist realism and Brecht‟s view on it. In order to discuss third part of my paper I will analyze film maker Satyajit Ray and his socialist- realist- fantasy film Hirak Rajar Deshe. The movie is adapted from Ray‟s father‟s collection of work for children name Goopy Gayen and Bagha Bayen. Keywords: Fantasy, Reality, Realism, Socialism, Brecht. www.ijellh.com 50 Children‟s literature is a genre that is vastly dependent on fantastic elements that make it appealing to children and adults. The fantastic elements, on the surface, act as a model for psychologically cushioning that protects the child from the harsh realities of life and bestow moral messages to the masses. But the fantastical element alone cannot reveal the social, political, or moral message the fiction intends to spread. The fantasy element is hence paradoxical complicated by the presence of realism in Children‟s Literature. The use of realism, in the façade of fantasy, and larger than life characters, has helped writers to adhere to the real intention of children‟s literature. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

Pather Panchali

February 19, 2002 (V:5) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921,Calcutta, West Bengal, India—23 April 1992, Calcutta) is one of the half-dozen universally P ATHER P ANCHALI acknowledged masters of world cinema. Perhaps the best starting place for information on him is the excellent UC Santa Cruz (1955, 115 min., 122 within web site, the “Satjiyat Ray Film and Study Collection” http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/. It's got lists of books by and about Ray, a Bengal) filmography, and much more, including an excellent biographical essay by Dilip Bausu ( Also Known As: The Lament of the http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/detail.html) from which the following notes are drawn: Path\The Saga of the Road\Song of the Road. Language: Bengali Ray was born in 1921 to a distinguished family of artists, litterateurs, musicians, scientists and physicians. His grand-father Upendrakishore was an innovator, a writer of children's story books, popular to this day, an illustrator and a musician. His Directed by Satyajit Ray father, Sukumar, trained as a printing technologist in England, was also Bengal's most beloved nonsense-rhyme writer, Written by Bibhutibhushan illustrator and cartoonist. He died young when Satyajit was two and a half years old. Bandyopadhyay (also novel) and ...As a youngster, Ray developed two very significant interests. The first was music, especially Western Classical music. Satyajit Ray He listened, hummed and whistled. He then learned to read music, began to collect albums, and started to attend concerts Original music by Ravi Shankar whenever he could. -

A Marxist Study of Ray's Film Hirak Rajar Deshe

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY– SEPT 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 “Dori Dhore Maro Taan / Raja Hobe Khan Khan”: A Marxist Study of Ray’s Film Hirak Rajar Deshe Dayal Chakrabortty* & Sambhunath Maji** *Independent Research Scholar, The University of Burdwan, W.B. **Assistant Professor, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, W.B. Received: May 30, 2018 Accepted: July 14, 2018 ABSTRACT From the very uncalendered past of society when system of production started its journey, automatically ‘class-struggle’ started to accompany it. Class-struggle is everywhere. In the age of slavery there was class struggle between slave-owners and slaves, in the age of Feudalism the class-struggle was between landowners and serfs and in capitalist society there is also class-struggle between Bourgeoisie and Proletariat. Lower class people or working class people or Proletariat people are always suppressed and oppressed by upper class people or the capitalists. This is the major aspect of Marxism. This Marxist approach is very much there in the Film Hirak Rajar Deshe directed by Satyajit Ray. Keywords: Class-Struggle, Capitalist Society, System of Production, Bourgeoisie and Proletariat, Marxism. “Marxist criticism has the longest history. Karl Marx himself made important general statements about culture and society in the 1850s. It is correct to think of Marxist criticism as a 20 th century phenomenon” (Selden, Widdowson, and Brooker 82). Marxism depends on temporal – spatial reality. The appropriation and application of it entirely depends on the consideration of time and place. Marxism is very much open to change. Karl Marx opines for a change for the betterment. -

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity DARIUS COOPER San Diego Mesa College PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written perrnission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt. System QuarkXpress® [mg] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cooper, Darius, 1949– The cinema of Satyajit Ray : between tradition and modernity / Darius Cooper p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in film) Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 62026 0 (hb). – isbn 0 521 62980 2 (pb) 1. Ray, Satyajit, 1921–1992 – Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series pn1998.3.r4c88 1999 791.43´0233´092 – dc21 99–24768 cip isbn 0 521 62026 0 hardback isbn 0 521 62980 2 paperback Contents List of Illustrations page ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Between Wonder, Intuition, and Suggestion: Rasa in Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy and Jalsaghar 15 Rasa Theory: An Overview 15 The Excellence Implicit in the Classical Aesthetic Form of Rasa: Three Principles 24 Rasa in Pather Panchali (1955) 26 Rasa in Aparajito (1956) 40 Rasa in Apur Sansar (1959) 50 Jalsaghar (1958): A Critical Evaluation Rendered through Rasa 64 Concluding Remarks 72 2. -

Sushant Singh Rajput Mar. 22

OC WHY FACEBOOK IS THE RUSH FOR MS DHONI: THE FRIENDING THE BJP GREEN CLEARANCES QUIET LONG WALK www.indiatoday.in AUGUST 31, 2020 `75 REGISTERED NO. DL(ND)-11/6068/2018-20;REGISTERED NO. U(C)-88/2018-20; FARIDABAD/05/2020-22 LICENSED POSTWITHOUTTO PREPAYMENT SuShant Singh Rajput 1986—2020 RNI NO. 28587/75 28587/75 NO. RNI SUICIDE OR MURDER? QUESTIONS ABOUT THE DEATH OF SUSHANT SINGH RAJPUT THAT REFUSE TO DIE DOWN. AN INVESTIGATION FROM THE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF hen the makers of a biopic on Indian crick- no faith in the Mumbai police’s investigation. The Bihar et captain Mahendra Singh Dhoni wanted police took cognisance of the complaint, filed an FIR and a Bollywood star to play the titular role, followed it up with an investigation. As part of the process, W they didn’t have to look beyond Sushant they turned up in Mumbai, triggering the political battle Singh Rajput. Not only were the actor and the cricketer between the two states and their police machinery. The born and raised in the same state, but their careers Enforcement Directorate has also joined the investigations were also mirror images of each other. Both were rank because of the accusations of money-laundering. outsiders who had broken into their fiercely competitive professions by dint of sheer talent. Inspirational stories n India, if there is any controversy worth taking ad- of self-made stars are the stuff of cinematic dreams. Yet, Ivantage of, politics can never be far behind. The Bihar not even the finest scriptwriter could have imagined the elections are barely two months away, and Sushant’s death drama around Sushant Singh Rajput’s tragic death on has become cause celebre for politicians to exploit in the June 14. -

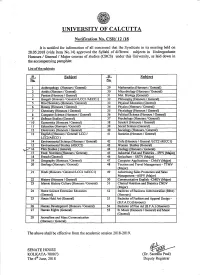

DRAFT STRUCTURE of BA/Bsc FILM STUDIES (GENERAL) SYLLABUS, UNIVERSITY of CALCUTTA, UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM to Be Effective from the Academic Session 2018-19

DRAFT STRUCTURE OF BA/BSc FILM STUDIES (GENERAL) SYLLABUS, UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA, UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM To be effective from the academic session 2018-19 PREAMBLE As the subject Film Studies falls under both BA and BSc two types of structures are proposed for BA/BSc Film Studies (General) - one for BA Film Studies (General) and the other for BSc Film Studies (General). For any student with Honours in any subject, may opt for Film Studies as a Generic Elective subject (GE). So provisions are to be kept for Film Studies Generic Elective for four courses (papers). For any BSc (General) student, they may opt for Film Studies as one of the three Core Subject, with related 2 (two) Skill Enhancement Course in Film Studies (SEC) and 2 (two) Discipline Specific Elective (DSE) in Film Studies. For any BA (General) student, they may opt for Film Studies as one of the two Core Subjects, with related Skill Enhancement Course (SEC) in Film Studies and Discipline Specific Elective (DSE) in Film Studies or as a Generic Elective subject (GE). OUTLINE OF CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM Academic Year: Two consecutive (one odd + one even) semesters constitute one academic year. Course: Usually referred to, as ‘papers’ is a component of a programme. All courses need not carry the same weight. The courses should define learning objectives and learning outcomes. Different courses may have different distribution of marks. A course may be designed to comprise lectures/ tutorials/laboratory work/ field work/ outreach activities/ project work/ vocational training/viva/ seminars/ term papers/assignments/ presentations/ self-study etc.