OA 72 Part 03 Hawkins Layout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Nations Histories (Revised 10.11.06)

First Nations Histories (revised 10.11.06) Greeting Cards from the Court of Leaves Abenaki | Acolapissa | Algonkin | Bayougoula | Beothuk | Catawba | Cherokee | Chickasaw | Chitimacha | Comanche | Delaware | Erie | Houma | Huron | Illinois | Iroquois | Kickapoo | Mahican | Mascouten | Massachusett | Mattabesic | Menominee | Metoac | Miami | Micmac | Mohegan | Montagnais | Narragansett | Nauset] Neutrals | Niantic] Nipissing | Nipmuc | Ojibwe | Ottawa | Pennacook | Pequot | Pocumtuc | Potawatomi | Sauk and Fox | Shawnee | Susquehannock | Tionontati | Tsalagi | Wampanoag | Wappinger | Wenro | Winnebago | Abenaki Native Americans have occupied northern New England for at least 10,000 years. There is no proof these ancient residents were ancestors of the Abenaki, but there is no reason to think they were not. Acolapissa The mild climate of the lower Mississippi required little clothing. Acolapissa men limited themselves pretty much to a breechcloth, women a short skirt, and children ran nude until puberty. With so little clothing with which to adorn themselves, the Acolapissa were fond of decorating their entire bodies with tattoos. In cold weather a buffalo robe or feathered cloak was added for warmth. Algonkin If for no other reason, the Algonkin would be famous because their name has been used for the largest native language group in North America. The downside is the confusion generated, and many people do not realize there actually was an Algonkin tribe, or that all Algonquins do not belong to the same tribe. Although Algonquin is a common language group, it has many many dialects, not all of which are mutually intelligible. Bayougoula Dogs were the only animal domesticated by Native Americans before the horse, but the Bayougoula in 1699 kept small flocks of turkeys. -

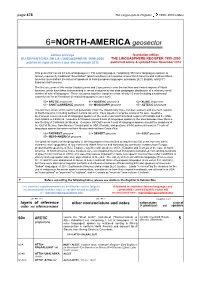

The Linguasphere Register. 1999 / 2000 Edition

page 478 The Linguasphere Register 1999 / 2000 edition 6=NORTH-AMERICA geosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This geosector covers 63 sets of languages (= 336 outer languages, comprising 978 inner languages) spoken or formerly spoken by traditional "Amerindian" (plus Inuit-Aleut) communities across North America and northern Meso- America (since before the arrival of speakers of Indo-European languages, principally [52=] English, and [51=] Español and Français). The first six zones of this sector (4 phylozones and 2 geozones) cover the northern and central regions of North America, which have been characterised in recent centuries by the wide geographic distribution of a relatively small number of sets of languages. These six zones together comprise a total of only 13 sets (including a southward extension as far as Honduras of related languages in zone 65=). 60= ARCTIC phylozone 61= NADENIC phylozone 62= ALGIC phylozone 63= SAINT-LAWRENCE geozone 64= MISSISSIPPI geozone 65= AZTECIC phylozone The last four zones of this sector (all geozones) cover the linguistically more complex western and southern regions of North America, including northern Central America. They together comprise a total of 50 sets. Geozone 66=Farwest covers 26 sets of languages spoken on the west-coast and hinterland regions of Canada and the USA, from Alaska to California. Geozone 67=Desert covers 5 sets of languages spoken in the area between New Mexico and the Bay of California (in Mexico). -

{PDF} Petun to Wyandot : the Ontario Petun from the Sixteenth Century

PETUN TO WYANDOT : THE ONTARIO PETUN FROM THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles Garrad | 656 pages | 12 May 2014 | University of Ottawa Press | 9780776621449 | English | Ottawa, Canada Petun to Wyandot : The Ontario Petun from the Sixteenth Century PDF Book The next year, the seat of the alliance shifts to the Wyandot town of Brownstown just outside of Detroit. Another century later, there were fewer than 1, Abenaki remaining after the american revolution. Township maps, portraits and properties have been scanned, with links from the property owners' names in the database. After a ten-day siege, Chonnonton and Ottawa take and sack one of the main towns of the Asistagueronon. JS: Tell us about your working space, why it serves you well and how you might improve it. The other presenter using slides and I were amazed at the Power Point presentations given by the students and other young people. Seven years later, an unknown epidemic struck, with influenza passing through the following year. Each man had different hunting territories inherited through his father. In , the French attacked the Mohawks and burned all the Mohawk villages and their food supply. The Anishinaabe defended this territory against Haudenosaunee warriors in the seenteenth century and its integrity was at the core of the peace they concluded in Montreal in , a key element of which was the Naagan ge bezhig emkwaan, or Dish with One Spoon. JS: I know you love science fiction, for one, so how about you describe some of you favourite films, books, and TV shows of any genre and tell us why they interest you. -

Roberta Estes

Roberta Estes ect shows significantly less Native American ancestry than would be expected with 96% European or African Within genealogy circles, family stories of Native Y chromosomal DNA. The Melungeons, long held to be American1 heritage exist in many families whose Ameri- mixed European, African and Native show only one can ancestry is rooted in Colonial America and traverses ancestral family with Native DNA.4 Clearly more test- Appalachia. The task of finding these ancestors either ing would be advantageous in all of these projects. genealogically or using genetic genealogy is challenging. This phenomenon is not limited to these groups, and has With the advent of DNA testing, surname and other been reported by other researchers. For example, special interest projects, tools now exist to facilitate the Bolnick (2006) reports finding in 16 Native American tracing of patrilineal and matrilineal lines in present-day populations with northeast or southeast roots that 47% people, back to their origins in either Native Americans, of the families who believe themselves to be full-blooded Europeans, or Africans. This paper references and uses or no less than 75% Native with no paternal European data from several of these public projects, but particular- admixture, find themselves carrying European or ly the Melungeon, Lumbee, Waccamaw, North Carolina African Y chromosomes. Malhi et al. (2008) reported Roots and Lost Colony projects.2 that in 26 Native American populations, non-Native American Y chromosomes occurred at a frequency as The Lumbee have long claimed descent from the Lost high as 88% in the Canadian northeast, southwest of Colony via their oral history.3 The Lumbee DNA Proj- Hudson Bay. -

Wyandotte Nation History Brochure

Interesting historical facts: What does our turtle symbolize? » We were instrumental in the founding of Detroit, The Turtle – Signifies our ancient belief the Michigan and Kansas City, Kansas. Wyandotte City world was created on the back of a snapping was the original name for Kansas City, Kansas. turtle, also known as the “moss-back turtle.” » During the French and Indian War we sided Willow Branches - Because of its resilience with the French against the British. During the after winter or famine, our ancestors believed American Revolution we sided with the British the willow tree signified the perpetual renewal of life. against the Americans. » On Aug. 20, 1794 at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, all War Club and Peace Pipe - Shows that we ready for war but one of our thirteen chiefs participating in the or peace at any given moment. battle was killed. Council Fire - Many tribes of the Northeast looked upon Tarhe, the lone us for leadership and advice, when they came together survivor, signed the for council, we often hosted and presided over the councils Treaty of Greenville and are considered “Keepers of the Council Fire.” on Aug. 3, 1795. » We adopted many Points of the Shield - Represent each of our twelve clans; whites captives Big Turtle, Little Turtle, Mud Turtle, Wolf, Bear, Beaver, into the nation. Many, such as William Walker, Sr., Deer, Porcupine, Striped Turtle, Highland Turtle, Snake Robert Armstrong, Adam Brown and Isaac Zane, and Hawk. obtained high tribal status and made significant contributions to the betterment of the tribe. www.Wyandotte-Nation.org » In 1816, John 64700 E. -

Writing an Inclusive, Learning-Centered Syllabus

Writing an Inclusive, Learning- Centered Syllabus Adapted from Grunert O’Brien, J., Millis, B., & Cohen, M. (2008). (Second ed). The course syllabus. A learning-centered approach. San Francisco: Jossey Bass and Creating an inclusive syllabus, UCLA, Center for Education Innovation & Learning in the Sciences (Accessed January 6, 2020) by Gabriele Bauer, Director, VITAL, 106 Vasey Hall, Villanova University. The more explicit and transparent information we can provide our students about the course goals, their responsibilities, and the criteria we will use to assess their performance, the more likely it is that they will be successful as students and we will be successful as instructors. The syllabus serves as a central means to communicate such information. Modified from Grunert O’Brian, Millis, & Cohen, 2008, The course syllabus. This syllabus guide has been designed to assist you in developing an inclusive, learning-centered syllabus. As you work with this outline, consider the core elements (some required) and questions it presents. Feel free to modify so that your course syllabus most appropriately reflects the program, the course, and your approach to learning, teaching, and assessment. The guide highlights aspects of teaching that support an inclusive learning environment. Please use student-centered language when writing your syllabus; that is, the syllabus is written in first-person, and incorporates a text and tone that convey a welcoming, supportive, and encouraging climate for all students. The syllabus helps students understand the value of the course, how the course has been designed to contribute to their education as a whole person. 1. Course Logistics This section provides information about 1) instructor(s), 2) course, and 3) instructor personal information. -

Is for Aboriginal

Joseph MacLean lives in the Coast Salish traditional Digital territory (North Vancouver, British Columbia). A is for Aboriginal He grew up in Unama’ki (Cape Breton Island, Nova By Joseph MacLean Scotia) until, at the age of ten, his family moved to Illustrated by Brendan Heard the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) Territory (Montréal). Joseph is an historian by education, a storyteller by Is For Zuni A Is For Aboriginal avocation and a social entrepreneur by trade. Is For Z “Those who cannot remember the past are His mother, Lieut. Virginia Doyle, a WWII army Pueblo condemned to repeat it.” nurse, often spoke of her Irish grandmother, a country From the Spanish for Village healer and herbalist, being adopted by the Mi'kmaq. - George Santayana (1863-1952) Ancient Anasazi Aboriginal The author remembers the stories of how his great- American SouthwestProof grandmother met Native medicine women on her A is for Aboriginal is the first in the First ‘gatherings’ and how as she shared her ‘old-country’ A:shiwi is their name in their language Nations Reader Series. Each letter explores a knowledge and learned additional remedies from her The language stands alone name, a place or facet of Aboriginal history and new found friends. The author wishes he had written Unique, single, their own down some of the recipes that his mother used when culture. he was growing up – strange smelling plasters that Zuni pottery cured his childhood ailments. geometry and rich secrets The reader will discover some interesting bits of glaze and gleam in the desert sun history and tradition that are not widely known. -

Journal #2856

Journal #2856 from sdc 5.20.13 GEA National Geothermal Summit 2013 Indian Territory ‘Why I Farm’ to be released by Tahoe publisher GARDENS AND LEARNING, AND MORE Alice E. Kober, 43; Lost to History No More Statistics show trends in families The U.N. Wants You to Eat More Bugs Forest Service Seeks to Silence Smokey the Bear Over Fracking Extinct languages of North America Flaxseed: The Next Superfood For Cattle And Beef? Scholarships For College Students Miss Indian Nations Guatemala Genocide Conviction and a More Just Vision for American Continent GEA National Geothermal Summit 2013 The Geothermal Energy Association will host the third annual National Geothermal Summit (#GEASummit2013) at the Grand Sierra Resort and Casino in Reno, Nev., June 26-27. ****************************************************************************** Indian Territory www.youtube.com ****************************************************************************** ‘Why I Farm’ to be released by Tahoe publisher On: May 14, 2013 On June 6, Meyers’ publisher Bona Fide Books will release “Why I Farm: Risking It All for a Life on the Land” by Sierra Valley Farms owner Gary Romano. A book signing will be that evening from 6-7 at Campo restaurant in Reno. In “Why I Farm,” third-generation farmer Romano speaks from experience about today’s most vital issues: how to live with purpose and how to protect our food supply. The author documents a disappearing way of life and issues a wake-up call, describing his metamorphosis from a small boy growing up on a farm to adult white-collar worker and his ultimate return to the land. He details specific issues that small farms face today, and how they will challenge our food future. -

S T . Lawrence River

S T . L A W R E N C E R I V E R S O C I A L M E D I A C A M P A I G N T O O L K I T JOIN US ONLINE! IT'S #ALLABOUTTHERIVER FROM JULY 20 - 25, 2020 #OURRIVER #RESPECTTHERIVER It’s #AllAboutTheRiver from July 20 to 25 #OurRiver #RespectTheRiver Since 2018, the South Dundas Chamber of Commerce and South Nation Conservation (SNC) have partnered to host a community event along the Morrisburg Waterfront in July called “It’s All About The River”, dedicated to promoting the St. Lawrence River, the local environment and showcasing community partners. Due to COVID-19, the event for this year has been cancelled. We are instead showcasing the River and our local communities through a weeklong social media campaign from July 20th to 25th. Join us online, it’s easy! We’ve provided some draft posts and pictures you can share on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter throughout the week, on everything from the environment, history, and culture. SNC and the Chamber of Commerce will serve as campaign hosts; you can also simply share posts directly from our social media channels if that’s easier! Put your own spin on it! Edits posts or create your own! Our draft posts are meant to give you some ideas. To participate in the campaign, just use the hashtags: #OurRiver #AllAboutTheRiver #RespectTheRiver, and don’t forget to tag people! Remember to tag partners using their social media handles. Follow us online! www.facebook.com/SouthNationConservation www.facebook.com/SouthDundasChamber @SouthNationCA (Twitter & Instagram) www.nation.on.ca www.southdundaschamber.ca Include Pictures With Your Posts: Photo Bank Here. -

Minority Contributions to Science, Engineering, and Medicine

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 156 382 . RC 016 570 AUTHOR' . Punches, Peggy; And Others .' -TITLE '''Minority Contributions'to-Science Engineering, and .1411dicine. INSTITUTION Sin Diego- City Schools,. Calif. PUB DATE 78 NOTE 179p. - ENS PRICE AF-$0.83 HC- $10.03 plus postage. DESCRIPTORS *Achte'vement; American Indians; Asian Americans; *Biographical Inventories; Blacks; Cultural. Awareness; *Engineering; Ethnic Studies; Health -Personnel; Instructional Materials ;Leadership; *Medicine; *Minority Grcups;Pharmacy; *physical Sciences;. Resoureg Materials; Role Models; Sciences; Spanish Speaking ABSTRACT . Offering an historical pertpective on the development' = of science, engineering, _medicine, and technology and providing current role models for minprity students, the bulletin lists the outstanding contributions madeby: (1) Elad4s nedicine, chemistry, architecture, engineering, physics, biology, and ezploration4.- (2) Hispanos - biomedical research., botany, biologye-physicsi chemistry, space educatiolL physiology, Whematics, pharmacblogy, meteorology, Aceanography, sociology, geology,' anthropology, psychology,. engineering, electronics, and compiters; (3) Asian Americans - astronomy, engineering, technology, matbematics, medicine, health, physics, dentistry, chemistry, and space education; (4) American Indians - engineering, botany, physics, architecture, chemistry, , biology, agronomy, foregtry, environmental science, weather forecasting, science education; audiology, otolaryngology, archeology, nursing, Mathematics, anthropology, psychology, -

Mailed Docket

Presbytery of Genesee Valley STATED MEETING October 12, 2019 Dansville Presbyterian Church 3 School St, Dansville, NY 14437 CP Roger Estes, Moderator Rev Colin Pritchard, Moderator-elect Elder Susan Orr, Stated Clerk Elder Bob Mecredy, Treasurer MAILED DOCKET 8:30AM - ON-SITE SIGN IN OPENS 9:00AM – PRE-MEETINGS 10:15AM - BUSINESS MEETING BEGINS The Parkside Spiritual Development Center is offering pre-meeting tours beginning at 9am. Don’t miss this exciting time! • New Commissioners: Please contact the Presbytery Office (242-0080) to request a name badge and a Welcome to Presbytery resource booklet. • Minutes of previous Presbytery meetings are available on the web site at www.pbygenval.org/documents. They will be mailed to presbyters who do not have e-mail access. • Attendance: Since ministers and elder commissioners are required to attend presbytery meetings, presbyters who do not request excuses will be marked absent. Corrections to attendance from previous meetings will be made in the permanent record. Table of Contents History of Dansville Presbyterian Church .......................................................................................................... Page 2 Docket .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Consent Agenda ..................................................................................................................................................... 4-52 Committee on Ministry -

Medline Search Strategy 1. American Native Continental Ancestry Group/ Or Indians, North American/ Or Inuits/ 2. Indians, Centra

Medline Search Strategy 1. american native continental ancestry group/ or indians, north american/ or inuits/ 2. indians, central american/ 3. indians, south american/ 4. Oceanic Ancestry Group/ 5. United States Indian Health Service/ 6. Health Services, Indigenous/ 7. (Aborigin* or Indigenous or Eskimo* or Inuit* or Inuk* or Metis or First Nations or First Nation or 1st nation or 1st nations or Native Canadian* or Native American* or Maori* or Pacific Islander* or American Indian* or Amerindian* or Native Alaska* or Alaska Native* or Native Hawaiian* or Torres Strait Islander* or on-reserve or off-reserve or tribal or autochtone* or amerindien* or indigene*).tw,kw. 8. (indian or indians).tw,kw. 9. India/ or India.tw,kw. or India's.tw,kw. 10. 8 not 9 11. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 10 12. Pygmy peoples.tw. [Central Africa] 13. (Acholi or Alur or Ambo or Ankole or Antalote or Aushi or Aweer or Babongo or Baganda or Bahima or Ankole or Bagisu or Bagwere or Bakiga or Bakonjo or Basoga or Batoro or Bemba or Betsileo or Bisa or Bunyoro or Cafre or Chagga or Chewa or Chikunda or Chokwe or Chopi or Cishinga or Gova or Hadzabe or Haya or Hehe or Hutu or Ila or Inamwanga or Iteso or Iwa or Jopadhola or Kabende or Kalenjin or Kamba or Kaonde or Karamojong or Kikuyu or Kisii or Kosa or Kunda or Kwandi or Kwandu or Kwangwa or Lala or Lamba or Lango or Lenje or Leya or Lima or Liyuwa or Lomwe or Lozi or Luano or Lucazi or Lugbara or Luhya or Lumbu or Lunda or Lundwe or Lungu or Luo or Luvale or Luunda or Maasai or Makoa or Makoma or Makonde