Quindaro National Historic Landmark Application

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRM Vol. 21, No. 4

PUBLISHED BY THE VOLUME 21 NO. 4 1998 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Contents ISSN 1068-4999 To promote and maintain high standards for preserving and managing cultural resources Slavery and Resistance Foreword 3 Robert Stanton DIRECTOR Robert Stanton Slavery and Resistance—Expanding Our Horizon 4 ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR Frank Faragasso and Doug Stover CULTURAL RESOURCE STEWARDSHIP AND PARTNERSHIPS Revisiting the Underground Railroad 7 Katherine H. Stevenson Gary Collison EDITOR Ronald M. Greenberg The UGRR and Local History 11 Carol Kammen GUEST EDITORS Frank Faragasso Confronting Slavery and Revealing the "Lost Cause" 14 Doug Stover James Oliver Horton ADVISORS Changing Interpretation at Gettysburg NMP 17 David Andrews Editor.NPS Eric Foner and John A. Latschar Joan Bacharach Museum Registrar, NPS The Remarkable Legacy of Selina Gray 20 Randall I. Biallas Karen Byrne Historical Architect, NPS Susan Buggey Director. Historical Services Branch Frederick Douglass in Toronto 23 Parks Canada Hilary Russell lohn A. Burns Architect, NPS Harry A. Butowsky Local Pasts in National Programs 28 Historian, NPS Muriel Crespi Pratt Cassity Executive Director, National Alliance of Preservation Commissions The Natchez Court Records Project 30 Muriel Crespi Ronald L. F. Davis Cultural Anthropologist, NPS Mark R. Edwards The Educational Value of Quindaro Townsite in the 21st Century 34 Director. Historic Preservation Division, State Historic Preservation Officer. Georgia Michael M. Swann Roger E. Kelly Archeologist, NPS NPS Study to Preserve and Interpret the UGRR 39 Antoinette I- Lee John C. Paige Historian. NPS ASSISTANT The UGRR on the Rio Grande 41 Denise M. Mayo Aaron Mahr Yanez CONSULTANTS NPS Aids Pathways to Freedom Group 45 Wm. -

Pending Legislation Hearing Committee on Energy And

S. HRG. 115–535 PENDING LEGISLATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL PARKS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON S. 2395 S. 3533 H.R. 3607 S. 2895/H.R. 5613 S. 3534 H.R. 3961 S. 3291 S. 3571/H.R. 5420 H.R. 5005 S. 3439/H.R. 5532 S. 3646 H.R. 5706 S. 3468 S. 3609/H.R. 801 H.R. 6077 S. 3505 S. 3659 H.R. 6599 S. 3527/H.R. 5585 H.R. 1220 H.R. 6687 DECEMBER 12, 2018 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 33–662 WASHINGTON : 2019 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska, Chairman JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming MARIA CANTWELL, Washington JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho RON WYDEN, Oregon MIKE LEE, Utah BERNARD SANDERS, Vermont JEFF FLAKE, Arizona DEBBIE STABENOW, Michigan STEVE DAINES, Montana JOE MANCHIN III, West Virginia CORY GARDNER, Colorado MARTIN HEINRICH, New Mexico LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee MAZIE K. HIRONO, Hawaii JOHN HOEVEN, North Dakota ANGUS S. KING, JR., Maine BILL CASSIDY, Louisiana TAMMY DUCKWORTH, Illinois ROB PORTMAN, Ohio CATHERINE CORTEZ MASTO, Nevada SHELLEY MOORE CAPITO, West Virginia TINA SMITH, Minnesota SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL PARKS STEVE DAINES, Chairman JOHN BARRASSO ANGUS S. KING, JR. MIKE LEE BERNARD SANDERS CORY GARDNER DEBBIE STABENOW LAMAR ALEXANDER MARTIN HEINRICH JOHN HOEVEN MAZIE K. HIRONO ROB PORTMAN TAMMY DUCKWORTH BRIAN HUGHES, Staff Director KELLIE DONNELLY, Chief Counsel MICHELLE LANE, Professional Staff Member MARY LOUISE WAGNER, Democratic Staff Director SAM E. -

The Border Star

The Border Star Official Publication of the Civil War Round Table of Western Missouri “Studying the Border War and Beyond” March – April 2019 President’s Letter The Civil War Round Table Known as railway spine, stress syndrome, nostalgia, soldier's heart, shell of Western Missouri shock, battle fatigue, combat stress reaction, or traumatic war neurosis, we know it today as post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSS). Mis- 2019 Officers diagnosed for years and therefore improperly treated, our veterans are President --------- Mike Calvert now getting the help they need to cope and thrive in their lives. We know 1st V.P. -------------- Pat Gradwohl so much more today that will help the combat veteran. Now, I want you 2nd V.P. ------------- Terry Chronister Secretary ---------- Karen Wells to think back to the Civil War. There are many first person accounts of Treasurer ---------- Beverly Shaw the horrors of the battlefield. The description given by the soldier reads Historian ------------ Charles Bianco far worse that the latest slasher movie. It is no wonder that these soldiers Board Members suffered psychologically. Current study is delving into the PTSS of the Paul Bond Charles Childs front line Civil War soldier and there will be more in the future. My Michael Clay Pat Davis question is this, what about the men who sent all those soldiers into Steve Hatcher Barbara Hughes combat? John Moloski Barb Wormington Denis Wormington Lee and Grant are the first to come to mind. I know there are many, many Border Star Editor more; it’s just that these two men are the most universally known. -

Interpretive Grants Overview

Interpretive Grant Overview Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area (FFNHA) invites partner organizations to apply for Interpretive Grants. FFNHA awards small grants ($500-$1,500) and large grants ($1,501-$5,000) for projects that interpret their site’s story and connects it to the heritage area’s rich history. Grants will be awarded for projects aligned with the goals of Freedom’s Frontier, and one or more of these significant themes: Shaping the Frontier, Missouri Kansas Border War, Enduring Struggles for Freedom. Successful grants will be rooted in a context involving historic events in the heritage area that have broad regional or national impact Interpretive Grant Review Committee Grant Review Committee members are selected by the Advisory Committee in cooperation with staff. The committee is made up of a minimum of five members, with at least 25% being from each state. At least one member should represent historical societies and museums; at least one should represent convention & visitors bureaus or destination management organizations; at least one should represent battlefields, historic markers or trails. Committee members are selected because of their expertise in a program area, their knowledge of the heritage area and ability to make objective recommendations on grant funding. The committee reviews grant applications and ensure that grants awarded comply with FFNHA themes, mission and other grant guidelines. Interpretive Grant Awards Master List February 2012 Clinton Lake: The Clinton Lake Historical Society Incorporated (Wakarusa River Valley Heritage Museum) hosted a historical sites tour of Wakarusa Valley area. The sites have Civil War and Underground Railroad significance. Grant Request: $1,354.00 Eudora Area Historical Society: Eudora Area Historical Society created programs to supplement the Smithsonian Institution’s The Way We Worked Traveling Exhibit. -

Committee on Natural Resources Rob Bishop Chairman Markup Memorandum

Committee on Natural Resources Rob Bishop Chairman Markup Memorandum July 6, 2018 To: All Natural Resources Committee Members From: Majority Committee Staff— Terry Camp and Holly Baker Subcommittee on Federal Lands (x67736) Mark-Up: H.R. 5613 (Rep. Kevin Yoder), To designate the Quindaro Townsite in Kansas City, Kansas, as a National Historic Landmark, and for other purposes. July 11, 2018, 10:15 am; 1324 Longworth House Office Building ______________________________________________________________________________ H.R. 5613, “Quindaro Townsite National Historic Landmark Act” Summary of the Bill H.R. 5613, introduced by Representative Kevin Yoder (R-KS-03), would designate the Quindaro Townsite in Kansas City, Kansas, as a National Historic Landmark. Cosponsors Rep. Wm. Lacy Clay [D-MO-01] Rep. Emanuel Cleaver [D-MO-05] Rep. Ron Estes [R-KS-04] Rep. Lynn Jenkins [R-KS-02] Rep. Roger W. Marshall [R-KS-01] Background H.R. 5613 would designate the Quindaro Townsite in Kansas City, Kansas, as a National Historic Landmark. The Quindaro Townsite is on the National Register of Historic Places (listed in 2002), and is part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. The site preserves the ruins of a frontier town on the Missouri River, which was founded in 1857 to be a free-state port of entry during the Kansas Territory’s fight over the question of slavery. Other prominent river towns in the Territory at that time were pro-slavery. The town’s residents included euro-Americans, freed African Americans, and members of the Wyandot Tribe.1 1 National Register of Historic Place Registration Form for Quindaro Townsite. -

KANSAS CITY, KANSAS LANDMARKS COMMISSION June 3 2019 Minutes

KANSAS CITY, KANSAS LANDMARKS COMMISSION June 3 2019 Minutes The Kansas City, Kansas Landmarks Commission met in regular session on Monday, June 3, 2019, at 6:00 p.m., in the Commission Chamber of the Municipal Office Building, with the following members present: Mr. David Meditz, Chairman Presiding, Ms. Karen French, Vice Chairman, Mr. John Altevogt, Mr. Murrel Bland, Mr. Stephen Craddock, and Mr. Jim Schraeder, (Absent: Chamberlain, Taylor and Van Middlesworth.) Mrs. Melissa Sieben, Assistant County Administrator, Ms. Janet L. Parker, CSC/APC, Administrative Assistant, and Mr. Michael Farley, Planner, were also present. The minutes of the May 6, 2019 meeting were approved as distributed. Case Starts At :50: CERTIFICATE OF APPROPRIATENESS #CA-2019-2 – JAMES GARNETT – SYNOPSIS: Certificate of Appropriateness for the demolition of a house at 809 Oakland Avenue, within the 500 foot environs of Sumner High School and athletic field, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, Register of Historic Kansas Places and a Kansas City, Kansas Historic Landmark. Detailed Outline of Requested Action: This application has been submitted to demolish the home adjacent to the church. It is in the 500’ environs of Sumner High School and Athletic Fields. Recording Secretary Parker stated that this application was heard at the March meeting and was denied; the applicant was not present at the meeting. The applicant appealed the denial to the Unified Government Board of Commissioners which was heard on May 30, 2019. The Board of Commissioners referred the application back to the Landmarks Commission so it could hear the testimony from the applicant. Present in Support: Harold Simmons, representing the church James Garnett, applicant, representing the church Present in Opposition: No one appeared Staff Recommendation Starts At 10:18: Assistant County Administrator Sieben stated that the vacancy registry has been in effect for about one year and it was noted at the March meeting that this property should have been listed on the registry. -

First Nations Histories (Revised 10.11.06)

First Nations Histories (revised 10.11.06) Greeting Cards from the Court of Leaves Abenaki | Acolapissa | Algonkin | Bayougoula | Beothuk | Catawba | Cherokee | Chickasaw | Chitimacha | Comanche | Delaware | Erie | Houma | Huron | Illinois | Iroquois | Kickapoo | Mahican | Mascouten | Massachusett | Mattabesic | Menominee | Metoac | Miami | Micmac | Mohegan | Montagnais | Narragansett | Nauset] Neutrals | Niantic] Nipissing | Nipmuc | Ojibwe | Ottawa | Pennacook | Pequot | Pocumtuc | Potawatomi | Sauk and Fox | Shawnee | Susquehannock | Tionontati | Tsalagi | Wampanoag | Wappinger | Wenro | Winnebago | Abenaki Native Americans have occupied northern New England for at least 10,000 years. There is no proof these ancient residents were ancestors of the Abenaki, but there is no reason to think they were not. Acolapissa The mild climate of the lower Mississippi required little clothing. Acolapissa men limited themselves pretty much to a breechcloth, women a short skirt, and children ran nude until puberty. With so little clothing with which to adorn themselves, the Acolapissa were fond of decorating their entire bodies with tattoos. In cold weather a buffalo robe or feathered cloak was added for warmth. Algonkin If for no other reason, the Algonkin would be famous because their name has been used for the largest native language group in North America. The downside is the confusion generated, and many people do not realize there actually was an Algonkin tribe, or that all Algonquins do not belong to the same tribe. Although Algonquin is a common language group, it has many many dialects, not all of which are mutually intelligible. Bayougoula Dogs were the only animal domesticated by Native Americans before the horse, but the Bayougoula in 1699 kept small flocks of turkeys. -

THROUGH NUMBERS the Intersection of Abolitionist Politics, Freed Blacks, and a Flourishing Community in Quindaro

StrengthTHROUGH NUMBERS The Intersection of Abolitionist Politics, Freed Blacks, and a Flourishing Community in Quindaro PO Box 526 • 200 W 9th St. • Lawrence KS 66044 Phone: (785) 856-5300 [email protected] www.freedomsfrontier.org Symposium Report Freedom’s Frontier national Heritage Area 2017-2018 Symposium Sponsors Acknowledgments Balls Foods Barton P. and Mary D. Cohen Charitable Trust This page is still under construction. If you can help populate this list, please let staff know who Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area you know that needs to be listed here. Humanities Kansas Johnson County Community College, Kansas Studies Institute Kansas City Kansas Convention & Visitors Bureau, Inc. Kansas City, Kansas Public Library Kansas City Public Library Missouri Humanities Council Unifi ed Government of Wyandotte County and Kansas City, Kansas & Memorial Hall Staff University of Missouri – Kansas City • Bernardin-Haskell Lecture Fund • Department of History • The Black Studies Program • The Center for Midwestern Studies Paul Wenske Fred Whitehead Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area (FFNHA) is dedicated to building awareness of the struggles for freedom in western Missouri and eastern Kansas. These diverse, interwoven, and nationally important stories grew from a unique physical and cultural landscape. FFNHA inspires respect for multiple perspectives and empowers residents to preserve and share these stories. We achieve our goals through interpretation, preservation, conservation, and education for all residents and visitors. 13 Participation Feedback Contents and Evaluations Symposium Sponsors and Partners Inside Front Cover Contents 1 Quindaro Overview 2 Keynote Address 3 Symposium 4-9 Oral History Project 10 National Historic Landmark 11 Participant Feedback and Evaluations 12 Acknowledgments 13 On the Cover, top row, left to right: Dr. -

The Linguasphere Register. 1999 / 2000 Edition

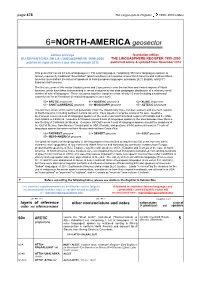

page 478 The Linguasphere Register 1999 / 2000 edition 6=NORTH-AMERICA geosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This geosector covers 63 sets of languages (= 336 outer languages, comprising 978 inner languages) spoken or formerly spoken by traditional "Amerindian" (plus Inuit-Aleut) communities across North America and northern Meso- America (since before the arrival of speakers of Indo-European languages, principally [52=] English, and [51=] Español and Français). The first six zones of this sector (4 phylozones and 2 geozones) cover the northern and central regions of North America, which have been characterised in recent centuries by the wide geographic distribution of a relatively small number of sets of languages. These six zones together comprise a total of only 13 sets (including a southward extension as far as Honduras of related languages in zone 65=). 60= ARCTIC phylozone 61= NADENIC phylozone 62= ALGIC phylozone 63= SAINT-LAWRENCE geozone 64= MISSISSIPPI geozone 65= AZTECIC phylozone The last four zones of this sector (all geozones) cover the linguistically more complex western and southern regions of North America, including northern Central America. They together comprise a total of 50 sets. Geozone 66=Farwest covers 26 sets of languages spoken on the west-coast and hinterland regions of Canada and the USA, from Alaska to California. Geozone 67=Desert covers 5 sets of languages spoken in the area between New Mexico and the Bay of California (in Mexico). -

{PDF} Petun to Wyandot : the Ontario Petun from the Sixteenth Century

PETUN TO WYANDOT : THE ONTARIO PETUN FROM THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles Garrad | 656 pages | 12 May 2014 | University of Ottawa Press | 9780776621449 | English | Ottawa, Canada Petun to Wyandot : The Ontario Petun from the Sixteenth Century PDF Book The next year, the seat of the alliance shifts to the Wyandot town of Brownstown just outside of Detroit. Another century later, there were fewer than 1, Abenaki remaining after the american revolution. Township maps, portraits and properties have been scanned, with links from the property owners' names in the database. After a ten-day siege, Chonnonton and Ottawa take and sack one of the main towns of the Asistagueronon. JS: Tell us about your working space, why it serves you well and how you might improve it. The other presenter using slides and I were amazed at the Power Point presentations given by the students and other young people. Seven years later, an unknown epidemic struck, with influenza passing through the following year. Each man had different hunting territories inherited through his father. In , the French attacked the Mohawks and burned all the Mohawk villages and their food supply. The Anishinaabe defended this territory against Haudenosaunee warriors in the seenteenth century and its integrity was at the core of the peace they concluded in Montreal in , a key element of which was the Naagan ge bezhig emkwaan, or Dish with One Spoon. JS: I know you love science fiction, for one, so how about you describe some of you favourite films, books, and TV shows of any genre and tell us why they interest you. -

Roberta Estes

Roberta Estes ect shows significantly less Native American ancestry than would be expected with 96% European or African Within genealogy circles, family stories of Native Y chromosomal DNA. The Melungeons, long held to be American1 heritage exist in many families whose Ameri- mixed European, African and Native show only one can ancestry is rooted in Colonial America and traverses ancestral family with Native DNA.4 Clearly more test- Appalachia. The task of finding these ancestors either ing would be advantageous in all of these projects. genealogically or using genetic genealogy is challenging. This phenomenon is not limited to these groups, and has With the advent of DNA testing, surname and other been reported by other researchers. For example, special interest projects, tools now exist to facilitate the Bolnick (2006) reports finding in 16 Native American tracing of patrilineal and matrilineal lines in present-day populations with northeast or southeast roots that 47% people, back to their origins in either Native Americans, of the families who believe themselves to be full-blooded Europeans, or Africans. This paper references and uses or no less than 75% Native with no paternal European data from several of these public projects, but particular- admixture, find themselves carrying European or ly the Melungeon, Lumbee, Waccamaw, North Carolina African Y chromosomes. Malhi et al. (2008) reported Roots and Lost Colony projects.2 that in 26 Native American populations, non-Native American Y chromosomes occurred at a frequency as The Lumbee have long claimed descent from the Lost high as 88% in the Canadian northeast, southwest of Colony via their oral history.3 The Lumbee DNA Proj- Hudson Bay. -

Wyandotte Nation History Brochure

Interesting historical facts: What does our turtle symbolize? » We were instrumental in the founding of Detroit, The Turtle – Signifies our ancient belief the Michigan and Kansas City, Kansas. Wyandotte City world was created on the back of a snapping was the original name for Kansas City, Kansas. turtle, also known as the “moss-back turtle.” » During the French and Indian War we sided Willow Branches - Because of its resilience with the French against the British. During the after winter or famine, our ancestors believed American Revolution we sided with the British the willow tree signified the perpetual renewal of life. against the Americans. » On Aug. 20, 1794 at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, all War Club and Peace Pipe - Shows that we ready for war but one of our thirteen chiefs participating in the or peace at any given moment. battle was killed. Council Fire - Many tribes of the Northeast looked upon Tarhe, the lone us for leadership and advice, when they came together survivor, signed the for council, we often hosted and presided over the councils Treaty of Greenville and are considered “Keepers of the Council Fire.” on Aug. 3, 1795. » We adopted many Points of the Shield - Represent each of our twelve clans; whites captives Big Turtle, Little Turtle, Mud Turtle, Wolf, Bear, Beaver, into the nation. Many, such as William Walker, Sr., Deer, Porcupine, Striped Turtle, Highland Turtle, Snake Robert Armstrong, Adam Brown and Isaac Zane, and Hawk. obtained high tribal status and made significant contributions to the betterment of the tribe. www.Wyandotte-Nation.org » In 1816, John 64700 E.