CRM Vol. 21, No. 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

Introducing Indiana-Past and Present

IndianaIntroducing PastPastPast ANDPresentPresent A book called a gazetteer was a main source of information about Indiana. Today, the Internet—including the Web site of the State of Indiana— provides a wealth of information. The Indiana Historian A Magazine Exploring Indiana History Physical features Physical features of the land Surficial have been a major factor in the growth and development of Indiana. topography The land of Indiana was affected by glacial ice at least three times Elevation key during the Pleistocene Epoch. The Illinoian glacial ice covered most of below 400 feet Indiana 220,000 years ago. The Wisconsinan glacial ice occurred 400-600 feet between 70,000 and 10,000 years ago. Most ice was gone from the area by 600-800 feet approximately 13,000 years ago, and 800-1000 feet the meltwater had begun the develop- ment of the Great Lakes. 1000-1200 feet The three maps at the top of these two pages provide three ways of above 1200 feet 2 presenting the physical makeup of the land. The chart at the bottom of page lowest point in Indiana, 320 feet 1 3 combines several types of studies to highest point in give an overview of the land and its 2 use and some of the unique and Indiana, 1257 feet unusual aspects of the state’s physical Source: Adapted from Indiana Geological Survey, Surficial To- features and resources. pography, <http:www.indiana. At the bottom of page 2 is a chart edu/~igs/maps/vtopo.html> of “normal” weather statistics. The first organized effort to collect daily weather data in Indiana began in Princeton, Gibson County in approxi- mately 1887. -

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 1997

National Register of Historic Places 1997 Weekly Lists WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 12/23/96 THROUGH 12/27/96 .................................... 3 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 12/30/96 THROUGH 1/03/97 ...................................... 5 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/06/97 THROUGH 1/10/97 ........................................ 8 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/13/97 THROUGH 1/17/97 ...................................... 12 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/20/97 THROUGH 1/25/97 ...................................... 14 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/27/97 THROUGH 1/31/97 ...................................... 16 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/03/97 THROUGH 2/07/97 ...................................... 19 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/10/97 THROUGH 2/14/97 ...................................... 21 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/17/97 THROUGH 2/21/97 ...................................... 25 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/24/97 THROUGH 2/28/97 ...................................... 28 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/03/97 THROUGH 3/08/97 ...................................... 32 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/10/97 THROUGH 3/14/97 ...................................... 34 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/17/97 THROUGH 3/21/97 ...................................... 36 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/24/97 THROUGH 3/28/97 ...................................... 39 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/31/97 THROUGH 4/04/97 ...................................... 41 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 4/07/97 THROUGH 4/11/97 ...................................... 43 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 4/14/97 THROUGH 4/18/97 ..................................... -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPSForm10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (Revised March 1992) . ^ ;- j> United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. _X_New Submission _ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing__________________________________ The Underground Railroad in Massachusetts 1783-1865______________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) C. Form Prepared by_________________________________________ name/title Kathrvn Grover and Neil Larson. Preservation Consultants, with Betsy Friedberg and Michael Steinitz. MHC. Paul Weinbaum and Tara Morrison. NFS organization Massachusetts Historical Commission________ date July 2005 street & number 220 Morhssey Boulevard________ telephone 617-727-8470_____________ city or town Boston____ state MA______ zip code 02125___________________________ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National -

Pending Legislation Hearing Committee on Energy And

S. HRG. 115–535 PENDING LEGISLATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL PARKS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON S. 2395 S. 3533 H.R. 3607 S. 2895/H.R. 5613 S. 3534 H.R. 3961 S. 3291 S. 3571/H.R. 5420 H.R. 5005 S. 3439/H.R. 5532 S. 3646 H.R. 5706 S. 3468 S. 3609/H.R. 801 H.R. 6077 S. 3505 S. 3659 H.R. 6599 S. 3527/H.R. 5585 H.R. 1220 H.R. 6687 DECEMBER 12, 2018 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 33–662 WASHINGTON : 2019 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska, Chairman JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming MARIA CANTWELL, Washington JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho RON WYDEN, Oregon MIKE LEE, Utah BERNARD SANDERS, Vermont JEFF FLAKE, Arizona DEBBIE STABENOW, Michigan STEVE DAINES, Montana JOE MANCHIN III, West Virginia CORY GARDNER, Colorado MARTIN HEINRICH, New Mexico LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee MAZIE K. HIRONO, Hawaii JOHN HOEVEN, North Dakota ANGUS S. KING, JR., Maine BILL CASSIDY, Louisiana TAMMY DUCKWORTH, Illinois ROB PORTMAN, Ohio CATHERINE CORTEZ MASTO, Nevada SHELLEY MOORE CAPITO, West Virginia TINA SMITH, Minnesota SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL PARKS STEVE DAINES, Chairman JOHN BARRASSO ANGUS S. KING, JR. MIKE LEE BERNARD SANDERS CORY GARDNER DEBBIE STABENOW LAMAR ALEXANDER MARTIN HEINRICH JOHN HOEVEN MAZIE K. HIRONO ROB PORTMAN TAMMY DUCKWORTH BRIAN HUGHES, Staff Director KELLIE DONNELLY, Chief Counsel MICHELLE LANE, Professional Staff Member MARY LOUISE WAGNER, Democratic Staff Director SAM E. -

The Border Star

The Border Star Official Publication of the Civil War Round Table of Western Missouri “Studying the Border War and Beyond” March – April 2019 President’s Letter The Civil War Round Table Known as railway spine, stress syndrome, nostalgia, soldier's heart, shell of Western Missouri shock, battle fatigue, combat stress reaction, or traumatic war neurosis, we know it today as post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSS). Mis- 2019 Officers diagnosed for years and therefore improperly treated, our veterans are President --------- Mike Calvert now getting the help they need to cope and thrive in their lives. We know 1st V.P. -------------- Pat Gradwohl so much more today that will help the combat veteran. Now, I want you 2nd V.P. ------------- Terry Chronister Secretary ---------- Karen Wells to think back to the Civil War. There are many first person accounts of Treasurer ---------- Beverly Shaw the horrors of the battlefield. The description given by the soldier reads Historian ------------ Charles Bianco far worse that the latest slasher movie. It is no wonder that these soldiers Board Members suffered psychologically. Current study is delving into the PTSS of the Paul Bond Charles Childs front line Civil War soldier and there will be more in the future. My Michael Clay Pat Davis question is this, what about the men who sent all those soldiers into Steve Hatcher Barbara Hughes combat? John Moloski Barb Wormington Denis Wormington Lee and Grant are the first to come to mind. I know there are many, many Border Star Editor more; it’s just that these two men are the most universally known. -

That's Not Fair!! Human Rights Violations During the 1800S Name

Title That’s Not Fair!! Human Rights Violations during the 1800s Name Kay Korty Date July 24, 2001 School Hall Elementary City/state Monrovia, IN *Teacher Teacher Resource List: Background Materials Coffin, Levi. Reminiscences of Levi Coffin: The Reputed President of the Underground Railroad. New York: Augustus M. Kelley Publishers, 1968.* Crenshaw, Gwendolyn J. Bury Me in a Free Land: The Abolitionist Movement in Indiana 1816-1865. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1993.* Student Reading List: Adler, David A. A Picture Book of Harriet Tubman. New York: Holiday House, 1992. Belcher-Hamilton, Lisa. “The Underground: The beginning of Douglass’s Journey.” Meeting Challenges. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1993. Bial, Raymond. The Underground Railroad. Boston: Houghton- Mifflin Company, 1995. Photographs of sites, eastern US map with routes, anecdotes, timeline. * Ferris, Jeri. Walking the Road to Freedom: A Story about Sojourner Truth. Minneapolis: Carolhoda Books Inc., 1988. Fradin, Dennis Brindell. My Family Shall Be Free! The Life of Peter Still. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2001. * Herbert, Janis. The Civil War for Kids. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1999. Timeline, quilt activity. * Hopkinson, Deborah. “Levi Coffin, President of the Underground Railroad.” Meeting Challenges. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1993. Rappaport, Doreen. Freedom River. New York: Hyperion Books for Children, 2000. Conductor John Parker rescues family by crossing Ohio River (non-fiction). * Ringgold, Faith. Aunt Harriet’s Underground Railroad in the Sky. New York: Crown Publishing, 1992. Quilts… Winter, Jeannette. Follow the Drinking Gourd. New York: Knopf, 1992. Song with music and lyrics. Internet Sites: http://www.cr.nps.gov National registry of UGRR sites. -

Interpretive Grants Overview

Interpretive Grant Overview Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area (FFNHA) invites partner organizations to apply for Interpretive Grants. FFNHA awards small grants ($500-$1,500) and large grants ($1,501-$5,000) for projects that interpret their site’s story and connects it to the heritage area’s rich history. Grants will be awarded for projects aligned with the goals of Freedom’s Frontier, and one or more of these significant themes: Shaping the Frontier, Missouri Kansas Border War, Enduring Struggles for Freedom. Successful grants will be rooted in a context involving historic events in the heritage area that have broad regional or national impact Interpretive Grant Review Committee Grant Review Committee members are selected by the Advisory Committee in cooperation with staff. The committee is made up of a minimum of five members, with at least 25% being from each state. At least one member should represent historical societies and museums; at least one should represent convention & visitors bureaus or destination management organizations; at least one should represent battlefields, historic markers or trails. Committee members are selected because of their expertise in a program area, their knowledge of the heritage area and ability to make objective recommendations on grant funding. The committee reviews grant applications and ensure that grants awarded comply with FFNHA themes, mission and other grant guidelines. Interpretive Grant Awards Master List February 2012 Clinton Lake: The Clinton Lake Historical Society Incorporated (Wakarusa River Valley Heritage Museum) hosted a historical sites tour of Wakarusa Valley area. The sites have Civil War and Underground Railroad significance. Grant Request: $1,354.00 Eudora Area Historical Society: Eudora Area Historical Society created programs to supplement the Smithsonian Institution’s The Way We Worked Traveling Exhibit. -

Committee on Natural Resources Rob Bishop Chairman Markup Memorandum

Committee on Natural Resources Rob Bishop Chairman Markup Memorandum July 6, 2018 To: All Natural Resources Committee Members From: Majority Committee Staff— Terry Camp and Holly Baker Subcommittee on Federal Lands (x67736) Mark-Up: H.R. 5613 (Rep. Kevin Yoder), To designate the Quindaro Townsite in Kansas City, Kansas, as a National Historic Landmark, and for other purposes. July 11, 2018, 10:15 am; 1324 Longworth House Office Building ______________________________________________________________________________ H.R. 5613, “Quindaro Townsite National Historic Landmark Act” Summary of the Bill H.R. 5613, introduced by Representative Kevin Yoder (R-KS-03), would designate the Quindaro Townsite in Kansas City, Kansas, as a National Historic Landmark. Cosponsors Rep. Wm. Lacy Clay [D-MO-01] Rep. Emanuel Cleaver [D-MO-05] Rep. Ron Estes [R-KS-04] Rep. Lynn Jenkins [R-KS-02] Rep. Roger W. Marshall [R-KS-01] Background H.R. 5613 would designate the Quindaro Townsite in Kansas City, Kansas, as a National Historic Landmark. The Quindaro Townsite is on the National Register of Historic Places (listed in 2002), and is part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. The site preserves the ruins of a frontier town on the Missouri River, which was founded in 1857 to be a free-state port of entry during the Kansas Territory’s fight over the question of slavery. Other prominent river towns in the Territory at that time were pro-slavery. The town’s residents included euro-Americans, freed African Americans, and members of the Wyandot Tribe.1 1 National Register of Historic Place Registration Form for Quindaro Townsite. -

KANSAS CITY, KANSAS LANDMARKS COMMISSION June 3 2019 Minutes

KANSAS CITY, KANSAS LANDMARKS COMMISSION June 3 2019 Minutes The Kansas City, Kansas Landmarks Commission met in regular session on Monday, June 3, 2019, at 6:00 p.m., in the Commission Chamber of the Municipal Office Building, with the following members present: Mr. David Meditz, Chairman Presiding, Ms. Karen French, Vice Chairman, Mr. John Altevogt, Mr. Murrel Bland, Mr. Stephen Craddock, and Mr. Jim Schraeder, (Absent: Chamberlain, Taylor and Van Middlesworth.) Mrs. Melissa Sieben, Assistant County Administrator, Ms. Janet L. Parker, CSC/APC, Administrative Assistant, and Mr. Michael Farley, Planner, were also present. The minutes of the May 6, 2019 meeting were approved as distributed. Case Starts At :50: CERTIFICATE OF APPROPRIATENESS #CA-2019-2 – JAMES GARNETT – SYNOPSIS: Certificate of Appropriateness for the demolition of a house at 809 Oakland Avenue, within the 500 foot environs of Sumner High School and athletic field, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, Register of Historic Kansas Places and a Kansas City, Kansas Historic Landmark. Detailed Outline of Requested Action: This application has been submitted to demolish the home adjacent to the church. It is in the 500’ environs of Sumner High School and Athletic Fields. Recording Secretary Parker stated that this application was heard at the March meeting and was denied; the applicant was not present at the meeting. The applicant appealed the denial to the Unified Government Board of Commissioners which was heard on May 30, 2019. The Board of Commissioners referred the application back to the Landmarks Commission so it could hear the testimony from the applicant. Present in Support: Harold Simmons, representing the church James Garnett, applicant, representing the church Present in Opposition: No one appeared Staff Recommendation Starts At 10:18: Assistant County Administrator Sieben stated that the vacancy registry has been in effect for about one year and it was noted at the March meeting that this property should have been listed on the registry. -

Black Evangelicals and the Gospel of Freedom, 1790-1890

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2009 SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890 Alicestyne Turley University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Turley, Alicestyne, "SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890" (2009). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 79. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/79 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Alicestyne Turley The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2009 SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890 _______________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _______________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Alicestyne Turley Lexington, Kentucky Co-Director: Dr. Ron Eller, Professor of History Co-Director, Dr. Joanne Pope Melish, Professor of History Lexington, Kentucky 2009 Copyright © Alicestyne Turley 2009 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890 The true nineteenth-century story of the Underground Railroad begins in the South and is spread North by free blacks, escaping southern slaves, and displaced, white, anti-slavery Protestant evangelicals. This study examines the role of free blacks, escaping slaves, and white Protestant evangelicals influenced by tenants of Kentucky’s Second Great Awakening who were inspired, directly or indirectly, to aid in African American community building. -

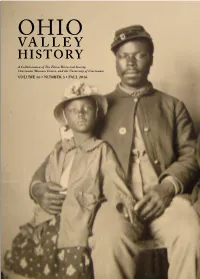

Volume 16 • Number 3 • Fall 2016

OHIO VALLEY HISTORY VALLEY OHIO Periodicals postage paid at Cincinnati, Ohio, and additional mailing offices. A Collaboration of The Filson Historical Society, Cincinnati Museum Center, and the University of Cincinnati. VOLUME 16 • NUMBER 3 • FALL 2016 VOLUME • NUMBER 16 3 • FALL 2016 Ohio Valley History is a Submission Information for Contributors to OHIO VALLEY STAFF David Stradling Phillip C. Long collaboration of The Filson University of Cincinnati Julia Poston Editors Nikki M. Taylor Thomas H. Quinn Historical Society, Cincinnati LeeAnn Whites Texas Southern University Joanna Reeder Museum Center, and the The Filson Historical Society Frank Towers Dr. Anya Sanchez Department of History, University Matthew Norman University of Calgary Judith K. Stein, M.D. Department of History Steve Steinman of Cincinnati. University of Cincinnati CINCINNATI Carolyn M. Tastad Blue Ash College MUSEUM CENTER Anne Drackett Thomas Cincinnati Museum Center and One digital copy of the manuscript, saved in Microsoft Word, *Regarding general form and style, please follow the BOARD OF TRUSTEES Albert W. Vontz III should be sent by email to: 16th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style. For The Filson Historical Society Book Review Editor Kevin Ward specific style guidelines, please visit The Filson’s web- William H. Bergmann Chair Donna Zaring are private non-profit organiza- Matthew Norman, Editor or LeeAnn Whites, Editor site at: http://www.filsonhistorical.org/programs- Department of History Edward D. Diller James M. Zimmerman tions supported almost entirely Ohio Valley History Ohio Valley History and-publications/publications/ohio-valley-history/ Slippery Rock University Asst. Professor of History Director of Research submissions/submissions-guidelines.aspx. -

All Indiana State Historical Markers As of 2/9/2015 Contact Indiana Historical Bureau, 317-232-2535, [email protected] with Questions

All Indiana State Historical Markers as of 2/9/2015 Contact Indiana Historical Bureau, 317-232-2535, [email protected] with questions. Physical Marker County Title Directions Latitude Longitude Status as of # 2/9/2015 0.1 mile north of SR 101 and US 01.1977.1 Adams The Wayne Trace 224, 6640 N SR 101, west side of 40.843081 -84.862266 Standing. road, 3 miles east of Decatur Geneva Downtown Line and High Streets, Geneva. 01.2006.1 Adams 40.59203 -84.958189 Standing. Historic District (Adams County, Indiana) SE corner of Center & Huron Streets 02.1963.1 Allen Camp Allen 1861-64 at playground entrance, Fort Wayne. 41.093695 -85.070633 Standing. (Allen County, Indiana) 0.3 mile east of US 33 on Carroll Site of Hardin’s Road near Madden Road across from 02.1966.1 Allen 39.884356 -84.888525 Down. Defeat church and cemetery, NW of Fort Wayne Home of Philo T. St. Joseph & E. State Boulevards, 02.1992.1 Allen 41.096197 -85.130014 Standing. Farnsworth Fort Wayne. (Allen County, Indiana) 1716 West Main Street at Growth Wabash and Erie 02.1992.2 Allen Avenue, NE corner, Fort Wayne. 41.078572 -85.164062 Standing. Canal Groundbreaking (Allen County, Indiana) 02.19??.? Allen Sites of Fort Wayne Original location unknown. Down. Guldin Park, Van Buren Street Bridge, SW corner, and St. Marys 02.2000.1 Allen Fort Miamis 41.07865 -85.16508333 Standing. River boat ramp at Michaels Avenue, Fort Wayne. (Allen County, Indiana) US 24 just beyond east interchange 02.2003.1 Allen Gronauer Lock No.