The Behram Yasht

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing Islam As Others Saw It

STUDIES IN LATE ANTIQUITY AND EARLY ISLAM 13 SEEING ISLAM AS OTHERS SAW IT A SURVEY AND EVALUATION OF CHRISTIAN, JEWISH AND ZOROASTRIAN WRITINGS ON EARLY ISLAM ROBERT G. HOYLAND THE DARWIN PRESS, INC. PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1997 Copyright © 1997 by THE DARWIN PRESS, INC., Princeton, NJ 08543. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles or reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hoyland, Robert G., 1966- Seeing Islam as others saw it : a survey and evaluation of Christian, Jewish, and Zoroastrian writings on early Islam / Robert G. Hoyland. p. cm. - (Studies in late antiquity and early Islam ; 13) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-87850-125-8 (alk. paper) 1. Islamic Empire-History-622-661-Historiography. 2. Islamic Empire-History-661-750- Historiography. 3. Middle East-Civilization-History-To 622-Historiography. I. Title. II. Series. DS38.1.H69 1997 939.4-dc21 97-19196 CIP Second Printing, 2001. The paper in this book is acid-free neutral pH stock and meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS Abbreviations Acknowledgements Introduction PART I The Historical and Literary Background 1. The Historical Background Late Antiquity to Early Islam: Continuity or Change? Identity and Allegiance Apocalypticism 2. -

On the Good Faith

On the Good Faith Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra and originated in ancient times. It was developed within the area populated by the Iranian peoples, and following the Arab conquest, it formed into a diaspora. In modern Russia it has evolved since the end of the Soviet era. It has become an attractive object of cultural produc- tion due to its association with Oriental philosophies and religions and its rearticulation since the modern era in Europe. The lasting appeal of Zoroastrianism evidenced by centuries of book pub- lishing in Russia was enlivened in the 1990s. A new, religious, and even occult dimension was introduced with the appearance of neo-Zoroastrian groups with their own publications and online websites (dedicated to Zoroastrianism). This study focuses on the intersectional relationships and topical analysis of different Zoroastrian themes in modern Russia. On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge [email protected] www.sh.se/publications On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola 2012 Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image: Anna Tessmann Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson & Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 68 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-86069-50-6 Avhandlingar utgivna vid -

Denkard Book 9

DENKARD, Book 9 Details of Nasks 1-3, 21 (The Original Gathic Texts) Translated by Edward William West From Sacred Books of the East, Oxford University Press, 1897. Digitized and converted to HTML 1997 Joseph H. Peterson, avesta.org. Last updated Mar 2, 2021. 1 Foreword The Denkard is a ninth century encyclopedia of the Zoroastrian religion, but with extensive quotes from materials thousands of years older, including (otherwise) lost Avestan texts. It is the single most valuable source of information on this religion aside from the Avesta. This volume contains detailed contents of the Gathic Nasks of the Ancient Canon, much of which is now lost in the original Avesta. Note however, that (as Dr. West says) “it is abundantly clear to the practised translator that Avesta phrases often underlie the Pahlavi passages which seem to be quoted at length from the original Nasks, especially in Dk. 9; but, for some of the details mentioned, there may be no older authority than a Pahlavi commentary, and this should be ever borne in mind by the sceptical critic in search of anachronisms.” I have added some comments in {} and [[]], mainly to facilitate searches. Spelling of technical terms have also been normalized to conform with other texts in this series. Wherever possible I have used the spellings of F.M. Kotwal and J. Boyd, A Guide to the Zoroastrian Religion, Scholars Press, 1982. The original S.B.E. volumes used a system of transliteration which was misleading to the casual reader, and no longer adopted. As an example “chinwad” (bridge) (Kotwal and Boyd) was transliterated in S.B.E. -

In the Alphabetic Order Q Follows A, a Follows E, C Follows C, 1J Follows N, S Follows S, I Follows Z

INDEX [In the alphabetic order q follows a, a follows e, c follows c, 1J follows n, s follows s, i follows z. In arranging words no distinction has been made between long and short vowels. Pahlavi anrllater forms are generally given in square brackets after the Avestan ones, ancl are entered separately only when there is a significant difference between the two.l Aban see Apas 273· A ban Niyayes 52; 271-2. Airyaman 56-7; his part at Fraso.kar<Jti, Aban Yast 73· 57. 242, 291. abstract divinities 23-4; 58, 59; 203. Airyanam Vaejah [f:ranve)] 144-5; 274- Aditi 55· S· Adityas 55; 83. Airyama isyo 56; 261; 263; 265. Adurbad i Mahraspandan 35; 288. Aiwisriithra [Aiwisriithrim] the 4th watch Aesma demon of Wrath, 87; companion ( giih) of the 24-hour day, from sunset till of the daevas, 201; flees at the last day midnight, 124; under the guardianship of before the Saosyant, 283; the Arabs are the fravasis, 124, 259. of his seed, 288. Aka Manah 283. aethrapati [erbad, herbad] 12. Akhtya 161. Afrasiyab see FralJrasyan *Ala demon of purpureal fever, 87 n. 20. afrinagan an "outer" religious ceremony, Amahraspand see Amasa Spanta 168; legends connected with the offerings Amestris xog; 112. made at it, 281. amaratat ,..., Ved. amrtatva-, "long life" after-life pagan belief in it beneath the or "immortality" II5 n. 32. earth, xog-xo, II2, IIS; in Paradise, no- Amaratat [Amurdad] personification of 12; Zoroastrian beliefs, 235-42, 328. "Long Life" and "Immortality", one of the Agni identified with Apam Napat, 45-6; 7 great Amasa Spantas (q.v.), 203; dis the nature of his primary concept, 69-70. -

Mecusi Geleneğinde Tektanrıcılık Ve Düalizm Ilişkisi

T.C. İSTANBUL ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ FELSEFE VE D İN B İLİMLER İ ANAB İLİM DALI DİNLER TAR İHİ B İLİM DALI DOKTORA TEZ İ MECUS İ GELENE Ğİ NDE TEKTANRICILIK VE DÜAL İZM İLİŞ KİSİ Mehmet ALICI (2502050181) Tez Danı şmanı: Prof.Dr. Şinasi GÜNDÜZ İstanbul 2011 T.C. İSTANBUL ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ FELSEFE VE D İN B İLİMLER İ ANAB İLİM DALI DİNLER TAR İHİ B İLİM DALI DOKTORA TEZ İ MECUS İ GELENE Ğİ NDE TEKTANRICILIK VE DÜAL İZM İLİŞ KİSİ Mehmet ALICI (2502050181) Tez Danı şmanı: Prof.Dr. Şinasi GÜNDÜZ (Bu tez İstanbul Üniversitesi Bilimsel Ara ştırma Projeleri Komisyonu tarafından desteklenmi ştir. Proje numarası:4247) İstanbul 2011 ÖZ Bu çalı şma Mecusi gelene ğinde tektanrıcılık ve düalizm ili şkisini ortaya çıkı şından günümüze kadarki tarihsel süreç içerisinde incelemeyi hedef edinir. Bu ba ğlamda Mecusilik üç temel teolojik süreç çerçevesinde ele alınmaktadır. Bu ba ğlamda birinci teolojik süreçte Mecusili ğin kurucusu addedilen Zerdü şt’ün kendisine atfedilen Gatha metninde tanrı Ahura Mazda çerçevesinde ortaya koydu ğu tanrı tasavvuru incelenmektedir. Burada Zerdü şt’ün anahtar kavram olarak belirledi ği tanrı Ahura Mazda ve onunla ili şkilendirilen di ğer ilahi figürlerin ili şkisi esas alınmaktadır. Zerdü şt sonrası Mecusi teolojisinin şekillendi ği Avesta metinleri ikinci teolojik süreci ihtiva etmektedir. Bu dönem Zerdü şt’ten önceki İran’ın tanrı tasavvurlarının yeniden kutsal metne yani Avesta’ya dahil edilme sürecini yansıtmaktadır. Dolayısıyla Avesta edebiyatı Zerdü şt sonrası dönü şen bir teolojiyi sunmaktadır. Bu noktada ba şta Ahura Mazda kavramı olmak üzere, Zerdü şt’ün Gatha’da ortaya koydu ğu mefhumların de ğişti ği görülmektedir. -

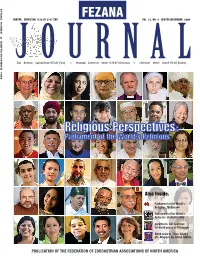

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA WINTER ZEMESTAN 1378 AY 3747 ZRE VOL. 23, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 JOURNALJODae – Behman – Spendarmad 1378 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1379 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1379 AY (Kadimi) Also Inside: Parliament oof the World’s Religions, Melbourne Parliamentt oof the World’s Religions:Religions: A shortshort hihistorystory Zarathustiss join in prayers for world peace in Pittsburgh Book revieew:w Thus Spake the Magavvs by Silloo Mehta PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA afezanajournal-winter2009-v15 page1-46.qxp 11/2/2009 5:01 PM Page 1 PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 23 No 4 Winter / December 2009 Zemestan 1378 AY - 3747 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 4ss Coming Event [email protected] Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 5 FEZANA Update [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: 16 Parliament of the World’s Religions Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] Yezdi Godiwalla [email protected] Behram Panthaki: [email protected] 47 In the News Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla -

Oral Character of Middle Persian Literature – New Perspective

ROCZNIK ORIENTALISTYCZNY, T. LXVII, Z. 1, 2014, (s. 151–168) MATEUSZ MIKOŁAJ KŁAGISZ Oral Character of Middle Persian Literature – New Perspective Abstract From the very beginning oral transmission of texts played a significant role in the Iranian world. It became a main topic of several works by Bailey (1943), Boyce (1957, 1968), de Menasce (1973), Skjærvø (1384hš), Smurzyński (2006) and Tafazzoli (1378hš). In my paper I try to depict the problem of orality in Middle Persian literature once again, but this time using some tools developed by Ong. On the other hand, it is highly likely that at least the “obscurity” is addressed to works of the 9th century that also contain material which at one time was transmitted orally, but which themselves were products of a written culture. Their style is difficult because the authors wrote in long, complicated sentences. Most of these sentences are in no way adopted to be transmitted by heart. Key words Middle Persian, literature, orality, influence In this article I would like to deal with the problem of orality and its influence on the formal structure of written Middle Persian texts. I use the adjective ‘written’ deliberately because most of Middle Persian texts, that we have at our disposal now, existed originally as unwritten and only later were written down. Paradoxically, it means that we are able to gain some information about orality literature only from some printed sources. The question of orality (and literacy) was elaborated by different Orientalists, but in my paper I am using Walter Jackson Ong’s method of analysis of texts existing first of all as acoustic waves.1 From this point of view, my paper is situated within the framework of today’s research on pre-Islamic literature in Iran but offers a new perspective. -

Change and Continuity in the Zoroastrian Tradition

CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN THE ZOROASTRIAN TRADITION AN INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED ON 22 FEBRUARY 2012 BY ALMUT HINTZE Zartoshty Professor of Zoroastrianism in the University of London SOAS, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN THE ZOROASTRIAN TRADITION AN INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED ON 22 FEBRUARY 2012 BY ALMUT HINTZE Zartoshty Professor of Zoroastrianism in the University of London SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The publication of this booklet was supported by a grant of the Zoroastrian Trust Funds of Europe. Published by the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London), Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square, London, WC1H 0XG. © Almut Hintze, 2013 Cover image: K. E. Eduljee, Zoroastrian Heritage Layout: Andrew Osmond, SOAS British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 07286 0400 1 Printed in Great Britain at SOAS, University of London. Dedicated to the memory of the brothers Faridoon and Mehraban Zartoshty, to that of Professor Mary Boyce and of an anonymous benefactor. Table of Contents Preface by the Director of SOAS 5 Preface by the President of the Zoroastrian Trust Funds of Europe 7 Change and Continuity in the Zoroastrian Tradition 11 PrefacebytheDirectorofSOAS ThelinksbetweenSOASandtheZoroastriancommunityreachrightbacktothe early years of SOAS.In 1929 a consortium of Zoroastrian benefactors from Bombayfundedthe‘ParseeCommunity’sLectureshipinIranianStudies’atSOAS on -

A History of Persian Literature Volume XVII Volumes of a History of Persian Literature

A History of Persian Literature Volume XVII Volumes of A History of Persian Literature I General Introduction to Persian Literature II Persian Poetry in the Classical Era, 800–1500 Panegyrics (qaside), Short Lyrics (ghazal); Quatrains (robâ’i) III Persian Poetry in the Classical Era, 800–1500 Narrative Poems in Couplet form (mathnavis); Strophic Poems; Occasional Poems (qat’e); Satirical and Invective poetry; shahrâshub IV Heroic Epic The Shahnameh and its Legacy V Persian Prose VI Religious and Mystical Literature VII Persian Poetry, 1500–1900 From the Safavids to the Dawn of the Constitutional Movement VIII Persian Poetry from outside Iran The Indian Subcontinent, Anatolia, Central Asia after Timur IX Persian Prose from outside Iran The Indian Subcontinent, Anatolia, Central Asia after Timur X Persian Historiography XI Literature of the early Twentieth Century From the Constitutional Period to Reza Shah XII Modern Persian Poetry, 1940 to the Present Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan XIII Modern Fiction and Drama XIV Biographies of the Poets and Writers of the Classical Period XV Biographies of the Poets and Writers of the Modern Period; Literary Terms XVI General Index Companion Volumes to A History of Persian Literature: XVII Companion Volume I: The Literature of Pre- Islamic Iran XVIII Companion Volume II: Literature in Iranian Languages other than Persian Kurdish, Pashto, Balochi, Ossetic; Persian and Tajik Oral Literatures A HistorY of Persian LiteratUre General Editor – Ehsan Yarshater Volume XVII The Literature of Pre-Islamic Iran Companion Volume I to A History of Persian Literature Edited by Ronald E. Emmerick & Maria Macuch Sponsored by Persian Heritage Foundation (New York) & Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University Published in 2009 by I. -

Zoroastrians Their Religious Beliefs and Practices

Library of Religious Beliefs and Practices General Editor: John R. Hinnells The University, Manchester In the series: The Sikhs W. Owen Cole and Piara Singh Sambhi Zoroastrians Their Religious Beliefs and Practices MaryBoyce ROUTLEDGE & KEGAN PAUL London, Boston and Henley HARVARD UNIVERSITY, UBRARY.: DEe 1 81979 First published in 1979 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd 39 Store Street, London WC1E 7DD, Broadway House, Newtown Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1EN and 9 Park Street, Boston, Mass. 02108, USA Set in 10 on 12pt Garamond and printed in Great Britain by Lowe & BrydonePrinters Ltd Thetford, Norfolk © Mary Boyce 1979 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Boyce, Mary Zoroastrians. - (Libraryof religious beliefs and practices). I. Zoroastrianism - History I. Title II. Series ISBN 0 7100 0121 5 Dedicated in gratitude to the memory of HECTOR MUNRO CHADWICK Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon in the University of Cambridge 1912-4 1 Contents Preface XJ1l Glossary xv Signs and abbreviations XIX \/ I The background I Introduction I The Indo-Iranians 2 The old religion 3 cult The J The gods 6 the 12 Death and hereafter Conclusion 16 2 Zoroaster and his teaching 17 Introduction 17 Zoroaster and his mission 18 Ahura Mazda and his Adversary 19 The heptad and the seven creations 21 .. vu Contents Creation and the Three Times 25 Death and the hereafter 27 3 The establishing of Mazda -

Zoroastrainism

Zoroastrainism Unit 3: Religions that Originate in the Middle East/Southwest Asia Zoroastrians in the World Today Country Population[1][2] Percent Population India 69,000 0.006 Iran 25,271 0.03[3] United States 11,000 0.004 Afghanistan 10,000 0.031 United Kingdom 4,105 [4] 0.007 Canada 5,000 0.014 Pakistan 5,000 0.003 Singapore 4,500 0.087 Azerbaijan 2,000 0.022 Australia 2,700 0.012 Persian Gulf Countries 2,200 0.005 New Zealand 2,000 0.045 Total 137,776 - Zoroastrianism Timeline ∗ 1600 BCE – Birth of Zarathustra (or Zoroaster) ∗ But could be 1400 BCE or 628 BCE ∗ 600 BCE – Zorastrianism expands in Iran ∗ 220-650 CE – Zorastrian Sasanid Empire in Iran ∗ 651 CE – Persecution begins under the rule of Arab Muslims ∗ 900 CE – Beginning of migration to India ∗ 1381 CE – Mongols kill thousands of Zoroastrians in Iran ∗ 1640-1720 – Continued persecutions and forced conversions in Afghanistan and Iran (continues into the 21st century) ∗ 18th-21st centuries – Migration of Zoroastrains to N. America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, etc. Origins of Zoroastrianism ∗Basis for Zoroastrianism is in Aryan religious traditions. ∗ Gods associated with nature ∗Above all the nature gods was one supreme god ∗ Called Ahura Mazda (or “Wise Lord”) The Life of Zoroaster ∗ Not much is really known about the true life of Zoroastrianism’s founder, Zarathustra Spitama (or Zoroaster in the Greek translation of his name) ∗ Might have been born into a noble family or a nomadic family or both ∗ Belief says that demons set out to kill the infant Zoroaster but he was -

Commonalities Between Yaj–A Ritual in India and Yasna Ritual in Iran

Indian Journal of History of Science, 51.4 (2016) 592-600 DOI: 10.16943/ijhs/2016/v51/i4/41236 Commonalities between Yaj–a Ritual in India and Yasna Ritual in Iran Azadeh Heidarpoor* and Fariba Sharifian* (Received 07 December 2015) Abstract Sacrifice ritual in India and ancient Iran has been of particular importance. This ritual is called Yaj–a and Yasna respectively in India and Iran. In Brāhmaas and later Avesta, it is considered as one of the most important religious ceremonies with commonalities and the same root. The most important commonalities in holding sacrifice rituals in Iran and India are fire elements, Iranian haoma or Indian soma drink after bloody or non-bloody sacrifices, and singing holy hymns [of praise] by spirituals who hold the rituals. Given the importance of these elements in both Yasna and Yaj–a ceremonies, we can find out their common root in a period before separation of Indian and Iranian peoples from each other and their settlement in India and Iran. Ancient Indo-Iranians believed that there were many divinities in the world and these divinities had to be worshiped to be calmed so that order is established in the world; along with sacrifices and offerings. Sacrifices and offerings were made in mainly, (1) to please gods; and (2) to establish order in a better manner in the management of world affairs. The ancient Indo-Iranians apart from performing their sacrifices to gods, they also worshiped two vital elements: water and fire, for they considered them vital and priceless in life. Indo-Iranians considered waters as goddesses whom they called Ops.