Commonalities Between Yaj–A Ritual in India and Yasna Ritual in Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIKYO ITO Kyoto Sangyo University in the Denkard We Read Jam's 10

JAM'S 10 PRECEPTS AND YASNA 32:8 (PAHLAVICA II)(1) GIKYOITO Kyoto Sangyo University In the Denkard we read Jam's 10 precepts and those of Azdahag in oppositionto them thus:(2) |adar 10 andarzi huramagJam |o |mardom <ud>(3)10 i dahisn kahenidar Dahag padirag |an andarz wirast. |az nigez i weh den. On the 10 precepts of Jam having beautiful flocks to mankind and the 10 (precepts) which established, against those precepts, Dahag, the diminisher of creation. From the exposition of the good religion. |had asn-xradzahag dam sud |weh den passand dadar kam. 10 i andarz i huramag Jam |o mardom. Now (here is) an emanation of the innate wisdom, an advantage of the creature, an object receiving the approbation of the good religion, a will of the creator. (That is) the 10 precepts of Jam having beautiful flocks to mankind. ek dadar i gehan [menidan] amurnjenidarih <i> gehan menidan guftan padis ostigan |estadan. (1) One (is) to think, say (and) stand steadfast in it that the creator of the world is not the injurer of the world. ud ek |dew |pad |tis abadih |ne yastan. (2) And one (is) not to worship dew(s) on account of whatever prosperity (of the world). ek dad mayan <mardoman>mehenidan ostigan ddstan. (3) One (is) to uplift the law among human beings (and) to keep (it) steadfastly. ek |abar |har |tis payman rayenidan ud frehbud ud abebud azis anaftan. (4) One (is) to arrange moderation over every matter and to avert from it excess and deficiency. ek |xwardan bradarwar《ciy bradaran》.(4) (5) One (is) to eat-and-drink brotherly《like brothers》. -

On the Good Faith

On the Good Faith Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra and originated in ancient times. It was developed within the area populated by the Iranian peoples, and following the Arab conquest, it formed into a diaspora. In modern Russia it has evolved since the end of the Soviet era. It has become an attractive object of cultural produc- tion due to its association with Oriental philosophies and religions and its rearticulation since the modern era in Europe. The lasting appeal of Zoroastrianism evidenced by centuries of book pub- lishing in Russia was enlivened in the 1990s. A new, religious, and even occult dimension was introduced with the appearance of neo-Zoroastrian groups with their own publications and online websites (dedicated to Zoroastrianism). This study focuses on the intersectional relationships and topical analysis of different Zoroastrian themes in modern Russia. On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge [email protected] www.sh.se/publications On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola 2012 Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image: Anna Tessmann Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson & Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 68 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-86069-50-6 Avhandlingar utgivna vid -

Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? a Study of Early Contacts Between Indo-Iranians and Chinese

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 216 October, 2011 Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? A Study of Early Contacts between Indo-Iranians and Chinese by ZHANG He Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Part Six: Yasna Haptanghaiti 35.2 and 3. This Revised Version Simply

Part Six: Yasna Haptanghaiti 35.2 and 3. This revised version simply corrects a spelling error. My apologies. Yasna Haptanghaiti 35. 2 and 3 The Yasna Haptanghaiti is not a part of the Gathas. Nor do we know who its author(s) may have been. The form in which it has come down to us in surviving manuscripts, is generally in Gathic Avestan, (with some additions in later forms of the Avestan language).1 So it would be reasonable to conclude that (except for the later Avestan parts) it was composed closer in time to Zarathushtra than other Avestan texts. And indeed, some parts of the Yasna Haptanghaiti are very close to his thought. This is true of the entire first chapter of the Yasna Haptanghaiti (YHapt. 35), but also of other parts. The opening paragraph (YHapt 35.1) is in archaic YAv. and therefore would have been added much later (some additional details are footnoted).2 But it also is quite beautiful and accurately reflects Zarathushtra's thought. It reads as follows. 'The truth--possessing Lord Wisdom, (having) the judgment of truth,3 we celebrate; The beneficial non--mortal (ones), good--ruling, good--giving, we celebrate; The truth--possessing existence of all (things), we celebrate -- belonging to the existences of mind, and physical life -- praiseworthy (because) of good truth, praiseworthy (because) of the good envisionment of wisdom-- worship." YHapt. 35.1. There are no capital letters in Av. script, and I take last word -- the name of the religion -- with double entendre, meaning the worship of wisdom, and the worship of the Existence that is Wisdom personified. -

Soma and Haoma: Ayahuasca Analogues from the Late Bronze Age

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(2), pp. 104–116 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.013 First published online July 25, 2019 Soma and Haoma: Ayahuasca analogues from the Late Bronze Age MATTHEW CLARK* School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), Department of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics, University of London, London, UK (Received: October 19, 2018; accepted: March 14, 2019) In this article, the origins of the cult of the ritual drink known as soma/haoma are explored. Various shortcomings of the main botanical candidates that have so far been proposed for this so-called “nectar of immortality” are assessed. Attention is brought to a variety of plants identified as soma/haoma in ancient Asian literature. Some of these plants are included in complex formulas and are sources of dimethyl tryptamine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and other psychedelic substances. It is suggested that through trial and error the same kinds of formulas that are used to make ayahuasca in South America were developed in antiquity in Central Asia and that the knowledge of the psychoactive properties of certain plants spreads through migrants from Central Asia to Persia and India. This article summarizes the main arguments for the botanical identity of soma/haoma, which is presented in my book, The Tawny One: Soma, Haoma and Ayahuasca (Muswell Hill Press, London/New York). However, in this article, all the topics dealt with in that publication, such as the possible ingredients of the potion used in Greek mystery rites, an extensive discussion of cannabis, or criteria that we might use to demarcate non-ordinary states of consciousness, have not been elaborated. -

Denkard Book 9

DENKARD, Book 9 Details of Nasks 1-3, 21 (The Original Gathic Texts) Translated by Edward William West From Sacred Books of the East, Oxford University Press, 1897. Digitized and converted to HTML 1997 Joseph H. Peterson, avesta.org. Last updated Mar 2, 2021. 1 Foreword The Denkard is a ninth century encyclopedia of the Zoroastrian religion, but with extensive quotes from materials thousands of years older, including (otherwise) lost Avestan texts. It is the single most valuable source of information on this religion aside from the Avesta. This volume contains detailed contents of the Gathic Nasks of the Ancient Canon, much of which is now lost in the original Avesta. Note however, that (as Dr. West says) “it is abundantly clear to the practised translator that Avesta phrases often underlie the Pahlavi passages which seem to be quoted at length from the original Nasks, especially in Dk. 9; but, for some of the details mentioned, there may be no older authority than a Pahlavi commentary, and this should be ever borne in mind by the sceptical critic in search of anachronisms.” I have added some comments in {} and [[]], mainly to facilitate searches. Spelling of technical terms have also been normalized to conform with other texts in this series. Wherever possible I have used the spellings of F.M. Kotwal and J. Boyd, A Guide to the Zoroastrian Religion, Scholars Press, 1982. The original S.B.E. volumes used a system of transliteration which was misleading to the casual reader, and no longer adopted. As an example “chinwad” (bridge) (Kotwal and Boyd) was transliterated in S.B.E. -

Ritual and Ritual Text in the Zoroastrian Tradition: the Extent of Yasna

Ritual and ritual text in the Zoroastrian tradition: The extent of Yasna ARASH ZEINI Abstract This article examines the extent of the concluding section (Y ) of the Yasna Haptaŋhaitī in light of the manuscript evidence and the section’s divergent reception in a Middle Persian text known as the “Supplementary Texts to the Šayest̄ ne ̄Šayest̄ ” (Suppl.ŠnŠ). This investigation will entertain the pos- sibility of an alternative ritual being described in the Suppl.ŠnŠ. Moreover, it argues that the manuscripts transmit the ritual text along with certain variations and repetitions while the descriptions of the extent of each section preserve the necessary boundaries of the text as a textual composition or unit. Keywords: Zoroastrianism; Yasna; Avestan; Middle Persian; Rituals The five Gaϑ̄as̄and the Yasna Haptaŋhaitī (“Yasna in seven sections”) constitute the core of the Old Avestan (OAv.) sections of the Yasna (Y), a Zoroastrian ritual text commonly divided into haitī (“section, chapter”) and at the centre of many Zoroastrian rituals.1 As Cantera recounts, Scholars have long debated the structure of the Old Avestan texts, examining the age of the divisions of the Gaϑ̄as̄into haitī.2 In that same article, Cantera questions whether the Yasna Haptaŋhaitī (YH) originally consisted of seven haitī, arguing that despite its name the Yasna Haptaŋhaitī“was not originally divided into seven chapters”.3 1The yaϑāahūvairiiō(Y .) and airiiaman išiia (Y .) are also composed in Old Avestan. In my view, these constitute together with the yeŋhé̄hatām̨and the asˇə̣m vohūmoveable sections of the Zoroastrian ritual texts. Out of convenience, I refer to these sections as prayers. -

Mecusi Geleneğinde Tektanrıcılık Ve Düalizm Ilişkisi

T.C. İSTANBUL ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ FELSEFE VE D İN B İLİMLER İ ANAB İLİM DALI DİNLER TAR İHİ B İLİM DALI DOKTORA TEZ İ MECUS İ GELENE Ğİ NDE TEKTANRICILIK VE DÜAL İZM İLİŞ KİSİ Mehmet ALICI (2502050181) Tez Danı şmanı: Prof.Dr. Şinasi GÜNDÜZ İstanbul 2011 T.C. İSTANBUL ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ FELSEFE VE D İN B İLİMLER İ ANAB İLİM DALI DİNLER TAR İHİ B İLİM DALI DOKTORA TEZ İ MECUS İ GELENE Ğİ NDE TEKTANRICILIK VE DÜAL İZM İLİŞ KİSİ Mehmet ALICI (2502050181) Tez Danı şmanı: Prof.Dr. Şinasi GÜNDÜZ (Bu tez İstanbul Üniversitesi Bilimsel Ara ştırma Projeleri Komisyonu tarafından desteklenmi ştir. Proje numarası:4247) İstanbul 2011 ÖZ Bu çalı şma Mecusi gelene ğinde tektanrıcılık ve düalizm ili şkisini ortaya çıkı şından günümüze kadarki tarihsel süreç içerisinde incelemeyi hedef edinir. Bu ba ğlamda Mecusilik üç temel teolojik süreç çerçevesinde ele alınmaktadır. Bu ba ğlamda birinci teolojik süreçte Mecusili ğin kurucusu addedilen Zerdü şt’ün kendisine atfedilen Gatha metninde tanrı Ahura Mazda çerçevesinde ortaya koydu ğu tanrı tasavvuru incelenmektedir. Burada Zerdü şt’ün anahtar kavram olarak belirledi ği tanrı Ahura Mazda ve onunla ili şkilendirilen di ğer ilahi figürlerin ili şkisi esas alınmaktadır. Zerdü şt sonrası Mecusi teolojisinin şekillendi ği Avesta metinleri ikinci teolojik süreci ihtiva etmektedir. Bu dönem Zerdü şt’ten önceki İran’ın tanrı tasavvurlarının yeniden kutsal metne yani Avesta’ya dahil edilme sürecini yansıtmaktadır. Dolayısıyla Avesta edebiyatı Zerdü şt sonrası dönü şen bir teolojiyi sunmaktadır. Bu noktada ba şta Ahura Mazda kavramı olmak üzere, Zerdü şt’ün Gatha’da ortaya koydu ğu mefhumların de ğişti ği görülmektedir. -

Dario Chioli, Sul Santo Haoma

SUL SANTO HAOMA Sommario I. Il Santo Haoma, che allontana la morte Dario Chioli II. La tetrade del Santo Haoma Ultimo aggiornamento III. Risposta a un internauta 7/6/2008 1 I. IL SANTO HAOMA, CHE ALLONTANA LA MORTE Del haoma (hauma, homa, hôm) parla l’Avesta (la sacra scrittura dei Parsi ovvero dei Mazdei, cioè dei seguaci di Zarathushtra) e in esso specialmente il Hôm Yasht, ovvero i capitoli 9, 10 e 11 dello Yasna. 2 Al suo equivalente vedico, il soma, sono dedicati nel Rgveda un gran numero di inni, 3 centoquattordici dei quali costituiscono da soli la nona sezione. Infatti «l’offerta di Haoma è il centro del sacrificio mazdeo, come l’offerta di Soma è il centro del sacrificio vedico. In ambedue i casi si tratta d’una pianta inebriante che concentra in sé tutte le virtù naturali e sovrannaturali della natura vegetale e la cui linfa, assaporata dal sacerdote, conferisce a lui ed alla comunità ogni felicità terrestre e celeste». 4 La letteratura in merito è pertanto abbastanza vasta, non manca il materiale di base. Sennonché, nonostante ciò, del haoma (come del soma) è in realtà tutto assai oscuro. Vi sono parecchi haoma, e quello celebrato in Airyanem Vaêjô da Zarathushtra, 5 che è egli stesso nato per sua virtù, non è lo stesso del haoma bianco (gaokerena) celato nel mare Vouru- kasha (che nell’ora della risurrezione darà l’immortalità a coloro che erano morti), che a sua volta non è la pianta che dà il haoma dorato bevuto dal sacerdote, che a sua volta non è la stessa nel tempo e nello spazio. -

A Historical Overview of the Parsi Settlement in Navsari 62 9

Samuel Jordan Center for Persian Studies and Culture www.dabirjournal.org Digital Archive of Brief notes & Iran Review ISSN: 2470-4040 Vol.01 No.04.2017 1 xšnaoθrahe ahurahe mazdå Detail from above the entrance of Tehran’s fire temple, 1286š/1917–18. Photo by © Shervin Farridnejad The Digital Archive of Brief Notes & Iran Review (DABIR) ISSN: 2470-4040 www.dabirjournal.org Samuel Jordan Center for Persian Studies and Culture University of California, Irvine 1st Floor Humanities Gateway Irvine, CA 92697-3370 Editor-in-Chief Touraj Daryaee (University of California, Irvine) Editors Parsa Daneshmand (Oxford University) Arash Zeini (Freie Universität Berlin) Shervin Farridnejad (Freie Universität Berlin) Judith A. Lerner (ISAW NYU) Book Review Editor Shervin Farridnejad (Freie Universität Berlin) Advisory Board Samra Azarnouche (École pratique des hautes études); Dominic P. Brookshaw (Oxford University); Matthew Canepa (University of Minnesota); Ashk Dahlén (Uppsala University); Peyvand Firouzeh (Cambridge University); Leonardo Gregoratti (Durham University); Frantz Grenet (Collège de France); Wouter F.M. Henkelman (École Pratique des Hautes Études); Rasoul Jafarian (Tehran University); Nasir al-Ka‘abi (University of Kufa); Andromache Karanika (UC Irvine); Agnes Korn (Goethe Universität Frankfurt am Main); Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (University of Edinburgh); Jason Mokhtarain (University of Indiana); Ali Mousavi (UC Irvine); Mahmoud Omidsalar (CSU Los Angeles); Antonio Panaino (Univer- sity of Bologna); Alka Patel (UC Irvine); Richard Payne (University of Chicago); Khodadad Rezakhani (Princeton University); Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis (British Museum); M. Rahim Shayegan (UCLA); Rolf Strootman (Utrecht University); Giusto Traina (University of Paris-Sorbonne); Mohsen Zakeri (Univer- sity of Göttingen) Logo design by Charles Li Layout and typesetting by Kourosh Beighpour Contents Articles & Notes 1. -

Zoroastrianism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Search Zoroastrianism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss Main page these issues on the talk page. Contents The neutrality of this article is disputed. (March 2012) Featured content This article may contain previously unpublished synthesis of Current events published material that conveys ideas not attributable to the Random article original sources. (March 2012) Donate to Wikipedia This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often Interaction accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (March 2012) Help Part of a series on About Wikipedia Zoroastrianism /ˌzɒroʊˈæstriənɪzəm/, also called Mazdaism Zoroastrianism Community portal and Magianism, is an ancient Iranian religion and a religious Recent changes philosophy. It was once the state religion of the Achaemenid, Contact page Parthian, and Sasanian empires. Estimates of the current number of Zoroastrians worldwide vary between 145,000 and Toolbox 2.6 million.[1] Print/export In the eastern part of ancient Persia more than a thousand The Faravahar, believed to be a depiction of a fravashi years BCE, a religious philosopher called Zoroaster simplified Languages Primary topics the pantheon of early Iranian gods[2] into two opposing forces: Afrikaans Ahura Mazda Ahura Mazda (Illuminating Wisdom) and Angra Mainyu Alemannisch Zarathustra (Destructive Spirit) which were in conflict. aša (asha) / arta Angels and demons ا open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Angels and demons ا Aragonés Zoroaster's ideas led to a formal religion bearing his name by Amesha Spentas · Yazatas about the 6th century BCE and have influenced other later Asturianu Ahuras · Daevas Azərbaycanca religions including Judaism, Gnosticism, Christianity and Angra Mainyu [3] Беларуская Islam. -

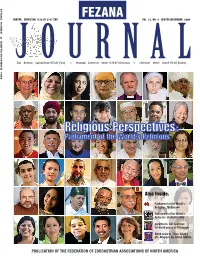

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA WINTER ZEMESTAN 1378 AY 3747 ZRE VOL. 23, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 JOURNALJODae – Behman – Spendarmad 1378 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1379 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1379 AY (Kadimi) Also Inside: Parliament oof the World’s Religions, Melbourne Parliamentt oof the World’s Religions:Religions: A shortshort hihistorystory Zarathustiss join in prayers for world peace in Pittsburgh Book revieew:w Thus Spake the Magavvs by Silloo Mehta PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA afezanajournal-winter2009-v15 page1-46.qxp 11/2/2009 5:01 PM Page 1 PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 23 No 4 Winter / December 2009 Zemestan 1378 AY - 3747 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 4ss Coming Event [email protected] Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 5 FEZANA Update [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: 16 Parliament of the World’s Religions Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] Yezdi Godiwalla [email protected] Behram Panthaki: [email protected] 47 In the News Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla