Dario Chioli, Sul Santo Haoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? a Study of Early Contacts Between Indo-Iranians and Chinese

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 216 October, 2011 Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? A Study of Early Contacts between Indo-Iranians and Chinese by ZHANG He Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Soma and Haoma: Ayahuasca Analogues from the Late Bronze Age

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(2), pp. 104–116 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.013 First published online July 25, 2019 Soma and Haoma: Ayahuasca analogues from the Late Bronze Age MATTHEW CLARK* School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), Department of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics, University of London, London, UK (Received: October 19, 2018; accepted: March 14, 2019) In this article, the origins of the cult of the ritual drink known as soma/haoma are explored. Various shortcomings of the main botanical candidates that have so far been proposed for this so-called “nectar of immortality” are assessed. Attention is brought to a variety of plants identified as soma/haoma in ancient Asian literature. Some of these plants are included in complex formulas and are sources of dimethyl tryptamine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and other psychedelic substances. It is suggested that through trial and error the same kinds of formulas that are used to make ayahuasca in South America were developed in antiquity in Central Asia and that the knowledge of the psychoactive properties of certain plants spreads through migrants from Central Asia to Persia and India. This article summarizes the main arguments for the botanical identity of soma/haoma, which is presented in my book, The Tawny One: Soma, Haoma and Ayahuasca (Muswell Hill Press, London/New York). However, in this article, all the topics dealt with in that publication, such as the possible ingredients of the potion used in Greek mystery rites, an extensive discussion of cannabis, or criteria that we might use to demarcate non-ordinary states of consciousness, have not been elaborated. -

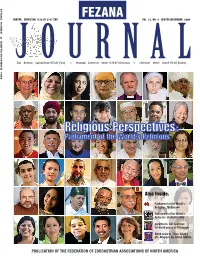

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA WINTER ZEMESTAN 1378 AY 3747 ZRE VOL. 23, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 JOURNALJODae – Behman – Spendarmad 1378 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1379 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1379 AY (Kadimi) Also Inside: Parliament oof the World’s Religions, Melbourne Parliamentt oof the World’s Religions:Religions: A shortshort hihistorystory Zarathustiss join in prayers for world peace in Pittsburgh Book revieew:w Thus Spake the Magavvs by Silloo Mehta PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA afezanajournal-winter2009-v15 page1-46.qxp 11/2/2009 5:01 PM Page 1 PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 23 No 4 Winter / December 2009 Zemestan 1378 AY - 3747 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 4ss Coming Event [email protected] Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 5 FEZANA Update [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: 16 Parliament of the World’s Religions Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] Yezdi Godiwalla [email protected] Behram Panthaki: [email protected] 47 In the News Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla -

THE SAUMA CONTROVERSY AFTER 1968 for More Than Two Centuries Western Scholarship Has Engaged in the Quest for the Original, Prot

THE SAUMA CONTROVERSY AFTER 1968 For more than two centuries Western scholarship has engaged in the quest for the original, Proto-Indo-Iranian (PIIr.) plant, the accepted com- mon origin of the remarkably concordant Indian soma and Iranian haoma traditions1. Despite many valuable contributions the botanical identity of sauma remains the issue of a lively controversy, which, nev- ertheless, has made substantial progress on various parts of the problem during the last three decades. Until the publication of Soma: divine mushroom of immortality by Wasson (1968), sauma was generally believed to be the fermented juice of a plant2. Today it is recognized that the duration of the rituals does not allow enough time for fermentation to take place, and that, since the reli- gious literature lacks unequivocal references to this process3, the phar- macological origin of sauma’s intoxication is rather to be found in psy- chotropic alkaloids4. Precisely the definition of sauma’s mada, however, is a stumbling block and, as the present author believes, the very cause of scholarly dis- agreement on its botanical identity5. Since the beginning of sauma research a sharp distinction has been drawn between the frequent refer- ences to the strengthening action of soma and haoma and the more obscure allusions to some kind of ecstatic visionary experience6. Whether one opts for the PIIr. cult of a stimulant, or adheres to the hypothetical use of a more spectacular drug, is very much dependent on one’s general conception of the Aryan religions. 1 Cf. the exhaustive status quaestionis by O’Flaherty (1968). 2 Among the few exceptions note cannabis and ‘mountain rue’. -

Commonalities Between Yaj–A Ritual in India and Yasna Ritual in Iran

Indian Journal of History of Science, 51.4 (2016) 592-600 DOI: 10.16943/ijhs/2016/v51/i4/41236 Commonalities between Yaj–a Ritual in India and Yasna Ritual in Iran Azadeh Heidarpoor* and Fariba Sharifian* (Received 07 December 2015) Abstract Sacrifice ritual in India and ancient Iran has been of particular importance. This ritual is called Yaj–a and Yasna respectively in India and Iran. In Brāhmaas and later Avesta, it is considered as one of the most important religious ceremonies with commonalities and the same root. The most important commonalities in holding sacrifice rituals in Iran and India are fire elements, Iranian haoma or Indian soma drink after bloody or non-bloody sacrifices, and singing holy hymns [of praise] by spirituals who hold the rituals. Given the importance of these elements in both Yasna and Yaj–a ceremonies, we can find out their common root in a period before separation of Indian and Iranian peoples from each other and their settlement in India and Iran. Ancient Indo-Iranians believed that there were many divinities in the world and these divinities had to be worshiped to be calmed so that order is established in the world; along with sacrifices and offerings. Sacrifices and offerings were made in mainly, (1) to please gods; and (2) to establish order in a better manner in the management of world affairs. The ancient Indo-Iranians apart from performing their sacrifices to gods, they also worshiped two vital elements: water and fire, for they considered them vital and priceless in life. Indo-Iranians considered waters as goddesses whom they called Ops. -

First Evaluation of Haoma Culture in Oluz Höyük

TÜBA-AR 22/2018 FIRST EVALUATION OF HAOMA CULTURE IN OLUZ HÖYÜK OLUZ HÖYÜK’TE HAOMA KÜLTÜRÜNÜN İLK DEĞERLENDİRMESİ Makale Bilgisi Article Info Başvuru: 16 Mart 2018 Received: March 16, 2018 Hakem Değerlendirmesi: 21 Mart 2018 Peer Review: March 21, 2018 Kabul: 10 Nisan 2018 Accepted: April 10, 2018 DOI Numarası: 10.22520/tubaar.2018.22.009 DOI Number: 10.22520/tubaar.2018.22.009 Mona SABA *1 Keywords: Haoma, Zoroastrian, Ritual, Mortar, Ephedra, Peganum Harmala, Oluz Höyük Anahtar Kelimeler: Haoma, Zerdüştlük, Ayin, Havan, Efedra, Peganum Harmala, Oluz Höyük ABSTRACT Oluz Höyük had made us distinguish some evidence regarding Anatolian Iron Age archaeology and ancient history that we haven’t noticed until today. With detection of Achaemenid (Persian) elements on 2B and 2A Architectural Layers (425-200 BC) which were alien to the local Anatolian culture, a change of excavation strategy had become necessary. As a result of this changes, the evidence uncovered on the work intensified in 2B and 2A Architectural Layers had proved that the Achaemenid culture that characterized the Oluz Höyük Late Iron Age had serious impact on the Anatolian historical process on the basis of religion, military and archaeo-ethnicity. Due to the various ritual ceremony in ancient Persia and the continuation of these celebrations, it is now helpful to review and compare them with each other to clarify some issues. One of the materials used in the Zoroastrianism ritual ceremony is Haoma. In this article, the study of the use of Haoma is based on the archaeological data obtained from Oluz Höyük and its environment. -

Mazdaism. the Religion of the Ancient Persians. Illustrated

MAZDAISM. BY THE EDITOR. MAZDAISM, the belief of the ancient Persians, is perhaps the most remarkable religion of antiquity, not only on account of the purity of its ethics, but also by reason of the striking similar- ities which it bears to Christianity. Ahura Mazda, the Lord Omniscient, is frequently represented (as seen in Fig. i) upon bas-reliefs of Persian monuments and rock Fig. I. Ahurx Mazda. (Conventional reproduction of the figure on the great rock inscription of Darius at Behistan.) inscriptions. He reveals himself through "the excellent, the pure and stirring Word," also called "the creative Word which was in the beginning," which reminds one not only of the Christian idea of the Logos, 6 Xoyos o? r)v iv oepx^, but also of the Brah- man Fdc/i, word (etymologically the same as the Latin vox), which is glorified in the fourth hymn of the Rig Veda, as "pervading heaven and earth, existing in all the worlds and extending to the heavens." 142 THE OPEN COURT. On the rock inscription of Elvend, which had been made by the order of King Darius, we read these Hnes^: " There is one God, omnipotent Ahura Mazda, It is who has created the earth here He ; It is has created the heaven there He who ; It is He who has created mortal man." Lenormant characterises the God of Zoroaster as follows : "Ahura Mazda has creaited as/ia, purity or rather the cosmic order; he has created both the moral and material world constitution ; he has made the universe; [datar], [ahura), he has made the law ; he is, in a word, creator sovereign omnis- Fig. -

The Monumental Iwan: a Symbolic Space Or a Functional Device ?

METUJFA 1991 (11:1-2) 5-19 THE MONUMENTAL IWAN: A SYMBOLIC SPACE OR A FUNCTIONAL DEVICE ? Ali Uzay PEKER INTRODUCTION Received : 27.1.1993 The architectural unit iwan consists of an empty vaulted space enclosed on three KeyWords: History of Architecture, Iwan, Courtyard with Four Cross-Axial Iwans, sides and open to a courtyard or central space on the fourth (Figure 1). Even Cosmology and Architecture. though the history of its application on a monumental scale is characterized by modifications that appear subtle and mainly related to periodic changes in taste, 1. This article is based on a lecture given the iwan was subject to continuous variation and interpretation in innumerable by the author on 14th April 1992, at METU small-scaled buildings. This article concerns the monumental iwan, whose persist Faculty of Architecture, with the title of 'Cosmoiogicai Images in the Seijukid ent application seems to have been governed by a definite cosmoiogicai scheme that Monumental Architecture'. The author dictated its orientation and function in the composition of an edifice (1). thanks Bruce Silverberg for reviewing the text. In Persian, iwan means 'portico, open gallery, porch or palace' and the word liwan in Arabic covers the Persian concept (Reuther, 1967,428). In Sassanid architec ture, the monumental iwan was used as an 'audience hair for the receptions of the kings. Its function in the Islamic period has always been a source of discus sion. It is unknown whether iwan served an official function or even whether these spaces were called iwan. Some written sources define the word iwan as a room or hall opening, on the one side, directly or by means of a portico towards outside. -

Uotta^A *4Bmct&&

PARAPSYCHOLOGY AND ALTERED STATES OF CONSCIOUSNESS TOWARDS A POINT OF INTEGRATION WITH RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE by Thomas M. Casey, O.S.A. Thesis presented to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Ottawa as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies BIBL'OTHEQUES &^bLI0\ pv uOtta^a *4BMCt&& Ottawa, Canada, 19 75 (c) T.M. Casey, Ottawa, Canada, 1976 UMI Number: DC53637 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform DC53637 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis was prepared under the supervision of Professor Peter Campbell, Ph.D., of the Department of Religious Studies of the University of Ottawa. The writer is indebted to Dr. Campbell and to his colleague, Dr. McMahon, for their constant guidance in relating one's research to the authenticating dynamic of one's own experiencing process. Gratitude is deeply expressed to the late Dr. Mary Andrew Hartmann, a woman of singular graciousness and dedication, for sharing her strengths and weaknesses and gently leading her students to explore the religious dimension of their own lives. -

Acta Iranica Encyclopedie Permanente Des Etudes Iraniennes Pubuee Par Le Centre Internatio:\A.L D'etudes Indo-Iraniennes

ACTA IRANICA ENCYCLOPEDIE PERMANENTE DES ETUDES IRANIENNES PUBUEE PAR LE CENTRE INTERNATIO:\A.L D'ETUDES INDO-IRANIENNES D1FFl!SIO~ EJ, BRILL LEIDEN La c rieur. decOl (Pho! Forse HOMMAGES ET OPERA MINORA PAPERS IN HONOUR OF PROFESSOR MARY BOYCE DIFFUSION E.J. BRILL LEIDEN The ancient act of worship of the Indo-Iranians, Vedic yaJna, Avestan yasna, is distinguished from other acts of worship by the fact that it is centred on the preparation, the purification, and the offering of a sacred plant, Iranian Haoma, Indian Soma. The plant was originally pounded in a stone mortar and purified by being strained through a sieve of bull's hair. Then it was mixed with water, milk, pomegranate, barley, perhaps honey, and other ingredients and offered as a libation to the gods. Thereafter it was drunk by the officiating priests and the other participants. Finally the remainder was poured back into pure water, a running stream or a well. 'It reproduced one of the great prototype sacrifices which in the beginning brought life into the world, in this case the life of plants, which sustain the existence of animals and men.' Whereas the role of Soma was later enhanced by the Indians, the role of Haoma 'was circumscribed and subordinated in ethical Zoroastrianism, although elements of its old power survive strongly even in the reformed faith.' (Boyce 1975: 156-157) 2. The problem of identifying the original plant is complicated by the fact that substitutes for the evidently rare, or unavailable, plant were introduced already in antiquity, and that the knowledge of the original plant had apparently been forgotten by the priests of both religions; according to Indian texts, it had to be 'stolen' or bought from a vendor (among others see Schneider 1971). -

A Thematic and Etymological Glossary of Aquatic and Bird Genera Names in Iranian Bundahis#M Khaksar, Mahdi; Ghalekhani, Golnar

www.ssoar.info A Thematic and Etymological Glossary of Aquatic and Bird Genera Names in Iranian Bundahis#m Khaksar, Mahdi; Ghalekhani, Golnar Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Khaksar, M., & Ghalekhani, G. (2015). A Thematic and Etymological Glossary of Aquatic and Bird Genera Names in Iranian Bundahis#m. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences, 62, 39-52. https://doi.org/10.18052/ www.scipress.com/ILSHS.62.39 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences Online: 2015-10-29 ISSN: 2300-2697, Vol. 62, pp 39-52 doi:10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILSHS.62.39 © 2015 SciPress Ltd., Switzerland A thematic and etymological glossary of aquatic and bird genera names in Iranian Bundahišm Golnar Ghalekhani1* and Mahdi Khaksar2 1Department of Foreign Languages and Linguistics, College of Literature and Humanities, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran 2Department of Foreign Languages and Linguistics, College of Literature and Humanities, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran *Corresponding author: [email protected] Keywords: thematic and etymological glossary, Iranian Bundašin, animal genera, aquatic, bird ABSTRACT. The purpose of this study is to present a thematic and etymological glossary of aquatic and bird genera names which have been mentioned in Iranian Bundahišn. In this research, after arranging animal names in Persian alphabetic order in their respective genus, first the transliteration and transcription of animal names in middle Persian language are provided. -

The Symbol of Zoroastrian Religion

THE SYMBOL OF ZOROASTRIAN RELIGION - Was designed during the reign of Achaemenian Dynasty, 600-500 B.C. Cyrus and Darius the Great were the two well-known kings of that dynasty. - The head represents wisdom which is emphasized in Zoroastrian religion. Ahura Mazda (The Supreme Creator) means The Wise Lord. - The raised index finger indicates one God. - The ring in the other hand means honoring contracts. Mithra which was the god of light with his seat being the sun, also was the supporter of sanctity of treaties. - Wings with 3 layer of feathers symbolize Good Thoughts, Good Words and Good Deeds. - The large circle represents this world of matter. - The two supports are the two natures of man (angelic and animal.) - The skirt is the worldly attachment. The message of this symbol is that with recognition of one God, with use of wisdom and trustworthiness and wings of Good Thoughts, Good Words and Good Deeds the angelic side of man could free him from the world of matter and lift him towards God. ZOROASTER - BAHA'U'LLAH'S ANCESTOR A transcript of audio-cassette from series WINDOWS TO THE PAST by Darius K. Shahrokh, M.D. ZOROASTER - BAHA'U'LLAH'S ANCESTOR A transcript of audio-cassette from series WINDOWS TO THE PAST by Darius K. Shahrokh, M.D. This presentation, which is a window from my heart, is dedicated to the memory of my father, Arbab Kaykhosrow Shahrokh, whose over thirty years of dedicated service as the leader and representative of the Zoroastrian Community of Iran elevated the status of that persecuted and impoverished minority from ignominy of being called infidel fire-worshippers and untouchables to the height of being considered the honorable descendants of original Persians, the noble ones.