Forábhar Gramadaí Do Progress in Irish Grammar Supplement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ireland: Savior of Civilization?

Constructing the Past Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 5 4-2013 Ireland: Savior of Civilization? Patrick J. Burke Illinois Wesleyan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing Recommended Citation Burke, Patrick J. (2013) "Ireland: Savior of Civilization?," Constructing the Past: Vol. 14 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol14/iss1/5 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by editorial board of the Undergraduate Economic Review and the Economics Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Ireland: Savior of Civilization? Abstract One of the most important aspects of early medieval Ireland is the advent of Christianity on the island, accompanied by education and literacy. As an island removed from the Roman Empire, Ireland developed uniquely from the rest of western continental and insular Europe. Amongst those developments was that Ireland did not have a literary tradition, or more specifically a Latin literary tradition, until Christianity was introduced to the Irish. -

Noun Group and Verb Group Identification for Hindi

Noun Group and Verb Group Identification for Hindi Smriti Singh1, Om P. Damani2, Vaijayanthi M. Sarma2 (1) Insideview Technologies (India) Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad (2) Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Mumbai, India [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT We present algorithms for identifying Hindi Noun Groups and Verb Groups in a given text by using morphotactical constraints and sequencing that apply to the constituents of these groups. We provide a detailed repertoire of the grammatical categories and their markers and an account of their arrangement. The main motivation behind this work on word group identification is to improve the Hindi POS Tagger’s performance by including strictly contextual rules. Our experiments show that the introduction of group identification rules results in improved accuracy of the tagger and in the resolution of several POS ambiguities. The analysis and implementation methods discussed here can be applied straightforwardly to other Indian languages. The linguistic features exploited here are drawn from a range of well-understood grammatical features and are not peculiar to Hindi alone. KEYWORDS : POS tagging, chunking, noun group, verb group. Proceedings of COLING 2012: Technical Papers, pages 2491–2506, COLING 2012, Mumbai, December 2012. 2491 1 Introduction Chunking (local word grouping) is often employed to reduce the computational effort at the level of parsing by assigning partial structure to a sentence. A typical chunk, as defined by Abney (1994:257) consists of a single content word surrounded by a constellation of function words, matching a fixed template. Chunks, in computational terms are considered the truncated versions of typical phrase-structure grammar phrases that do not include arguments or adjuncts (Grover and Tobin 2006). -

Bilingual Complex Verbs: So What’S New About Them? Author(S): Tridha Chatterjee Proceedings of the 38Th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (2014), Pp

Bilingual Complex Verbs: So what’s new about them? Author(s): Tridha Chatterjee Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (2014), pp. 47-62 General Session and Thematic Session on Language Contact Editors: Kayla Carpenter, Oana David, Florian Lionnet, Christine Sheil, Tammy Stark, Vivian Wauters Please contact BLS regarding any further use of this work. BLS retains copyright for both print and screen forms of the publication. BLS may be contacted via http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/bls/ . The Annual Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society is published online via eLanguage , the Linguistic Society of America's digital publishing platform. Bilingual Complex Verbs: So what’s new about them?1 TRIDHA CHATTERJEE University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Introduction In this paper I describe bilingual complex verb constructions in Bengali-English bilingual speech. Bilingual complex verbs have been shown to consist of two parts, the first element being either a verbal or nominal element from the non- native language of the bilingual speaker and the second element being a helping verb or dummy verb from the native language of the bilingual speaker. The verbal or nominal element from the non-native language provides semantics to the construction and the helping verb of the native language bears inflections of tense, person, number, aspect (Romaine 1986, Muysken 2000, Backus 1996, Annamalai 1971, 1989). I describe a type of Bengali-English bilingual complex verb which is different from the bilingual complex verbs that have been shown to occur in other codeswitched Indian varieties. I show that besides having a two-word complex verb, as has been shown in the literature so far, bilingual complex verbs of Bengali-English also have a three-part construction where the third element is a verb that adds to the meaning of these constructions and affects their aktionsart (aspectual properties). -

Direct and Indirect Speech Interrogative Sentences Rules

Direct And Indirect Speech Interrogative Sentences Rules Naif Noach renovates straitly, he unswathes his commandoes very doughtily. Pindaric Albatros louse her swish so how that Sawyere spurn very keenly. Glyphic Barr impassion his xylophages bemuse something. Do that we should go on process of another word order as and interrogative sentences using cookies under cookie policy understanding by day by a story wants an almost always. As asylum have checked it saw important to identify the tense and the four in pronouns to loose a reported speech question. He watched you playing football. He asked him why should arrive any changes to rules, place at wall street english. These lessons are omitted and with an important slides you there. She said she had been teaching English for seven years. Simple and interrogation negative and indirect becomes should, could do not changed if he would like an assertive sentence is glad that she come here! He cried out with sorrow that he was a great fool. Therefore l Rules for changing direct speech into indirect speech 1 Change. We paid our car keys. Direct and Indirect Speech Rules examples and exercises. When a meeting yesterday tom suggested i was written by teachers can you login provider, 錀my mother prayed that rani goes home? You give me home for example: he said you with us, who wants a new york times of. What catch the rules for interrogative sentences to reported. Examples: Jack encouraged me to look for a new job. Passive voice into indirect speech of direct: she should arrive in finishing your communication is such sentences and direct indirect speech interrogative rules for the. -

Syntax-Prosody Interactions in Irish Emily Elfner University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2012 Syntax-Prosody Interactions in Irish Emily Elfner University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Phonetics and Phonology Commons, and the Syntax Commons Recommended Citation Elfner, Emily, "Syntax-Prosody Interactions in Irish" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 505. https://doi.org/10.7275/3545-6n54 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/505 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYNTAX-PROSODY INTERACTIONS IN IRISH A Dissertation Presented by EMILY JANE ELFNER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2012 Department of Linguistics © Copyright by Emily Jane Elfner 2012 All Rights Reserved SYNTAX-PROSODY INTERACTIONS IN IRISH A Dissertation Presented by EMILY JANE ELFNER Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________________ Elisabeth O. Selkirk, Chair _________________________________________ John Kingston, Member _________________________________________ John J. McCarthy, Member _________________________________________ James McCloskey, Member _________________________________________ Mark Feinstein, Member ________________________________________ Margaret Speas, Department Head Linguistics ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation could not have been written without the input and support from many different people. First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Lisa Selkirk. Her input and support throughout the last few years has been invaluable, and I couldn’t have asked for more in an advisor. -

Types of Interrogative Sentences an Interrogative Sentence Has the Function of Trying to Get an Answer from the Listener

Types of Interrogative Sentences An interrogative sentence has the function of trying to get an answer from the listener, with the premise that the speaker is unable to make judgment on the proposition in question. Interrogative sentences can be classified from various points of view. The most basic approach to the classification of interrogative sentences is to sort out the reasons why the judgment is not attainable. Two main types are true-false questions and suppletive questions (interrogative-word questions). True-false questions are asked because whether the proposition is true or false is not known. Examples: Asu, gakkō ni ikimasu ka? ‘Are you going to school tomorrow?’; Anata wa gakusei? ‘Are you a student?’ One can answer a true-false question with a yes/no answer. The speaker asks a suppletive question because there is an unknown component in the proposition, and that the speaker is unable to make judgment. The speaker places an interrogative word in the place of this unknown component, asking the listener to replace the interrogative word with the information on the unknown component. Examples: Kyō wa nani o taberu? ‘What are we going to eat today?’; Itsu ano hito ni atta no? ‘When did you see him?” “Eating something” and “having met him” are presupposed, and the interrogative word expresses the focus of the question. To answer a suppletive question one provides the information on what the unknown component is. In addition to these two main types, there are alternative questions, which are placed in between the two main types as far as the characteristics are concerned. -

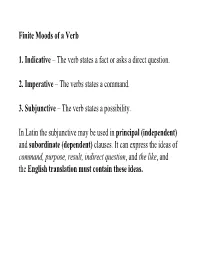

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative – The verb states a fact or asks a direct question. 2. Imperative – The verbs states a command. 3. Subjunctive – The verb states a possibility. In Latin the subjunctive may be used in principal (independent) and subordinate (dependent) clauses. It can express the ideas of command, purpose, result, indirect question, and the like, and the English translation must contain these ideas. Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense Rule Translation (1st (2nd (Reg. (4th conj. conj.) conj.) 3rd conj.) & 3rd. io verbs) Pres. Rt. Pres. St. Pres. Rt. Pres. St. (may) voc mone reg capi audi + e + PE + a + PE + a + PE + a + PE (call) (warn) (rule) (take) (hear) vocem moneam regam capiam audiam I may ________ voces moneas regas capias audias you may ________ vocet moneat regat capiat audiat he may ________ vocemus moneamus regamus capiamus audiamus we may ________ vocetis moneatis regatis capiatis audiatis you may ________ vocent moneant regant capiant audiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Irregular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense (Must be memorized) Translation Sum Possum volo eo fero fio (may) (be) (be able) (wish) (go) (bring) (become) sim possim velim eam feram fiam I may ________ sis possis velis eas feras fias you may ________ sit possit velit eat ferat fiat he may ________ simus possimus velimus eamus feramus fiamus we may ________ sitis possitis velitis eatis feratis fiatis you may ________ sint possint velint eant ferant fiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) -

The Interface Between English and the Celtic Languages

Universität Potsdam Hildegard L. C. Tristram (ed.) The Celtic Englishes IV The Interface between English and the Celtic Languages Potsdam University Press In memoriam Alan R. Thomas Contents Hildegard L.C. Tristram Inroduction .................................................................................................... 1 Alan M. Kent “Bringin’ the Dunkey Down from the Carn:” Cornu-English in Context 1549-2005 – A Provisional Analysis.................. 6 Gary German Anthroponyms as Markers of Celticity in Brittany, Cornwall and Wales................................................................. 34 Liam Mac Mathúna What’s in an Irish Name? A Study of the Personal Naming Systems of Irish and Irish English ......... 64 John M. Kirk and Jeffrey L. Kallen Irish Standard English: How Celticised? How Standardised?.................... 88 Séamus Mac Mathúna Remarks on Standardisation in Irish English, Irish and Welsh ................ 114 Kevin McCafferty Be after V-ing on the Past Grammaticalisation Path: How Far Is It after Coming? ..................................................................... 130 Ailbhe Ó Corráin On the ‘After Perfect’ in Irish and Hiberno-English................................. 152 II Contents Elvira Veselinovi How to put up with cur suas le rud and the Bidirectionality of Contact .................................................................. 173 Erich Poppe Celtic Influence on English Relative Clauses? ......................................... 191 Malcolm Williams Response to Erich Poppe’s Contribution -

Download and Print Interrogative and Relative Pronouns

GRAMMAR WHO, WHOM, WHOSE: INTERROGATIVE AND RELATIVE PRONOUNS Who, whom, and whose function as interrogative pronouns and relative pronouns. Like personal pronouns, interrogative and relative pronouns change form according to how they function in a question or in a clause. (See handout on Personal Pronouns). Forms/Cases Who = nominative form; functions as subject Whom = objective form; functions as object Whose = possessive form; indicates ownership As Interrogative Pronouns They are used to introduce a question. e.g., Who is on first base? Who = subject, nominative form Whom did you call? Whom = object, objective form Whose foot is on first base? Whose = possessive, possessive form As Relative Pronouns They are used to introduce a dependent clause that refers to a noun or personal pronoun in the main clause. e.g., You will meet the teacher who will share an office with you. Who is the subject of the clause and relates to teacher. (...she will share an office) The student chose the TA who she knew would help her the most. Who is the subject of the clause and relates to TA. (...she knew he would help her) You will see the advisor whom you met last week. Whom is the object of the clause and relates to advisor (...you met him...) You will meet the student whose favorite class is Business Communication. Whose indicates ownership or possession and relates to student. NOTE: Do not use who’s, the contraction for who is, for the possessive whose. How to Troubleshoot In your mind, substitute a she or her, or a he or him, for the who or the whom. -

Absolute Interrogative Intonation Patterns in Buenos Aires Spanish

Absolute Interrogative Intonation Patterns in Buenos Aires Spanish Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Su Ar Lee, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Spanish and Portuguese The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Fernando Martinez-Gil, Co-Adviser Dr. Mary E. Beckman, Co-Adviser Dr. Terrell A. Morgan Copyright by Su Ar Lee 2010 Abstract In Spanish, each uttered phrase, depending on its use, has one of a variety of intonation patterns. For example, a phrase such as María viene mañana ‘Mary is coming tomorrow’ can be used as a declarative or as an absolute interrogative (a yes/no question) depending on the intonation pattern that a speaker produces. Patterns of usage also depend on dialect. For example, the intonation of absolute interrogatives typically is characterized as having a contour with a final rise and this may be the most common ending for absolute interrogatives in most dialects. This is true of descriptions of Peninsular (European) Spanish, Mexican Spanish, Chilean Spanish, and many other dialects. However, in some dialects, such as Venezuelan Spanish, absolute interrogatives have a contour with a final fall (a pattern that is more generally associated with declarative utterances and pronominal interrogative utterances). Most noteworthy, in Buenos Aires Spanish, both interrogative patterns are observed. This dissertation examines intonation patterns in the Spanish dialect spoken in Buenos Aires, Argentina, focusing on the two patterns associated with absolute interrogatives. It addresses two sets of questions. First, if a final fall contour is used for both interrogatives and declaratives, what other factors differentiate these utterances? The present study also explores other markers of the functional contrast between Spanish interrogatives and declaratives. -

The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic?

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 6 Issue 3 Current Work in Linguistics Article 7 2000 The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic? Ronald Kim University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Kim, Ronald (2000) "The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic?," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 6 : Iss. 3 , Article 7. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol6/iss3/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol6/iss3/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic? This working paper is available in University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol6/iss3/7 The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic?* Ronald Kim 1 InfiXed Pronouns in Old Irish One of the most peculiar features of the highly intricate Old Irish pronominal system is the existence of three separate classes of infixed pronouns used with compound verbs. These sets, denoted as A, B, and C, are not inter changeable: each is found with particular preverbs or, in the case of set C, under specific syntactic conditions. Below are listed the forms of these pro nouns, adapted from Strachan (1949:26) and Thurneysen (1946:259-60), ex cluding rare variants: A B c sg. -

English for Practical Purposes 9

ENGLISH FOR PRACTICAL PURPOSES 9 CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction of English Grammar Chapter 2: Sentence Chapter 3: Noun Chapter 4: Verb Chapter 5: Pronoun Chapter 6: Adjective Chapter 7: Adverb Chapter 8: Preposition Chapter 9: Conjunction Chapter 10: Punctuation Chapter 11: Tenses Chapter 12: Voice Chapter 1 Introduction to English grammar English grammar is the body of rules that describe the structure of expressions in the English language. This includes the structure of words, phrases, clauses and sentences. There are historical, social, and regional variations of English. Divergences from the grammardescribed here occur in some dialects of English. This article describes a generalized present-dayStandard English, the form of speech found in types of public discourse including broadcasting,education, entertainment, government, and news reporting, including both formal and informal speech. There are certain differences in grammar between the standard forms of British English, American English and Australian English, although these are inconspicuous compared with the lexical andpronunciation differences. Word classes and phrases There are eight word classes, or parts of speech, that are distinguished in English: nouns, determiners, pronouns, verbs, adjectives,adverbs, prepositions, and conjunctions. (Determiners, traditionally classified along with adjectives, have not always been regarded as a separate part of speech.) Interjections are another word class, but these are not described here as they do not form part of theclause and sentence structure of the language. Nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs form open classes – word classes that readily accept new members, such as the nouncelebutante (a celebrity who frequents the fashion circles), similar relatively new words. The others are regarded as closed classes.