Hermaphrodite.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

Subjects of the Visual Arts: Hermaphrodites a Roman Copy of a Greek Sculpture of by Martin D

Subjects of the Visual Arts: Hermaphrodites A Roman copy of a Greek sculpture of by Martin D. Snyder Hermaphroditus (ca 200 C. E.). Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. This photograph appears under the the CeCILL Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. license and is attributed Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com to Rama. In classical mythology, the nymph Salmacis loved the handsome but unresponsive Hermaphroditus, son of Hermes and Aphrodite. When he bathed in her spring, she forcibly embraced him. As Hermaphroditus struggled to free himself, Salmacis prayed that they never part. The gods granted her wish, and the two became a single being with both male and female sexual characteristics. (Ovid, Metamorphoses, 4.285 ff.) In ancient art Hermaphroditus, either specifically or as a generalized type, is a common subject. He is either nude or lifts his garment to expose his genitals; alternatively, a satyr, who mistakes him for a woman, assaults him. The most famous portrayal represents Hermaphroditus asleep, lying on his stomach, head turned to the side, and torso twisted just enough to reveal his breast and genitals. (National Museum of the Terme, Rome, and the Louvre, Paris.) Hermaphrodites disappear from post-classical art history until the Renaissance, when writers of alchemical treatises rediscovered them as non-erotic symbols for the union of opposites (a potent image for later Jungian psychology), and emblem books portrayed them as symbols of marriage. (For a modern interpretation, see Marc Chagall's Homage to Appollinaire, 1911.) The tale of Hermaphroditus and Salmacis was portrayed occasionally in Renaissance and Neoclassical art. Among the depictions are the following: Jan Gossaert [Jan de Mabuse], The Metamorphosis of Hermaphroditus and the Nymph Salmacis (1505), Bartholomaeus Spranger, Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (1581), Francesco Albani, Salmacis Falling in Love with Hermaphroditus (ca 1660) and Salmacis Kissing Hermaphroditus in the Water (1660), and François-Joseph Navez, The Nymph Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (1829). -

TRANSGENDER JEWS and HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A

TRANSGENDER JEWS AND HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A. Sharzer MD This teshuvah was adopted by the CJLS on June 7, 2017, by a vote of 11 in favor, 8 abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Elliot Dorff, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, Jan Kaufman, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Daniel Nevins, Avram Reisner, and Iscah Waldman. Members abstaining: Rabbis Noah Bickart, Baruch Frydman- Kohl, Joshua Heller, David Hoffman, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Jonathan Lubliner, Micah Peltz, and Paul Plotkin. שאלות 1. What are the appropriate rituals for conversion to Judaism of transgender individuals? 2. What are the appropriate rituals for solemnizing a marriage in which one or both parties are transgender? 3. How is the marriage of a transgender person (which was entered into before transition) to be dissolved (after transition). 4. Are there any requirements for continuing a marriage entered into before transition after one of the partners transitions? 5. Are hormonal therapy and gender confirming surgery permissible for people with gender dysphoria? 6. Are trans men permitted to become pregnant? 7. How must healthcare professionals interact with transgender people? 8. Who should prepare the body of a transgender person for burial? 9. Are preoperative2 trans men obligated for tohorat ha-mishpahah? 10. Are preoperative trans women obligated for brit milah? 11. At what point in the process of transition is the person recognized as the new gender? 12. Is a ritual necessary to effect the transition of a trans person? The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halkhhah for the Conservative movement. -

The Transgender-Industrial Complex

The Transgender-Industrial Complex THE TRANSGENDER– INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX Scott Howard Antelope Hill Publishing Copyright © 2020 Scott Howard First printing 2020. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, besides select portions for quotation, without the consent of its author. Cover art by sswifty Edited by Margaret Bauer The author can be contacted at [email protected] Twitter: @HottScottHoward The publisher can be contacted at Antelopehillpublishing.com Paperback ISBN: 978-1-953730-41-1 ebook ISBN: 978-1-953730-42-8 “It’s the rush that the cockroaches get at the end of the world.” -Every Time I Die, “Ebolarama” Contents Introduction 1. All My Friends Are Going Trans 2. The Gaslight Anthem 3. Sex (Education) as a Weapon 4. Drag Me to Hell 5. The She-Male Gaze 6. What’s Love Got to Do With It? 7. Climate of Queer 8. Transforming Our World 9. Case Studies: Ireland and South Africa 10. Networks and Frameworks 11. Boas Constrictor 12. The Emperor’s New Penis 13. TERF Wars 14. Case Study: Cruel Britannia 15. Men Are From Mars, Women Have a Penis 16. Transgender, Inc. 17. Gross Domestic Products 18. Trans America: World Police 19. 50 Shades of Gay, Starring the United Nations Conclusion Appendix A Appendix B Appendix C Introduction “Men who get their periods are men. Men who get pregnant and give birth are men.” The official American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Twitter account November 19th, 2019 At this point, it is safe to say that we are through the looking glass. The volume at which all things “trans” -

Poikilia in the Book 4 of Alciphron's Letters

The Girlfriends’ Letters : Poikilia in the Book 4 of Alciphron’s Letters Michel Briand To cite this version: Michel Briand. The Girlfriends’ Letters : Poikilia in the Book 4 of Alciphron’s Letters. The Letters of Alciphron : To Be or not To be a Work ?, Jun 2016, Nice, France. hal-02522826 HAL Id: hal-02522826 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02522826 Submitted on 27 Mar 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THE GIRLFRIENDS’ LETTERS: POIKILIA IN THE BOOK 4 OF ALCIPHRON’S LETTERS Michel Briand Alciphron, an ambivalent post-modern Like Lucian of Samosata and other sophistic authors, as Longus or Achilles Tatius, Alciphron typically represents an ostensibly post-classical brand of literature and culture, which in many ways resembles our post- modernity, caught in permanent tension between virtuoso, ironic, critical, and distanced meta-fictionality, on the one hand, and a conscious taste for outspoken and humorous “bad taste”, Bakhtinian carnavalesque, social and moral margins, convoluted plots and sensational plays of immersion and derision, or realism and artificiality: the way Alciphron’s collection has been judged is related to the devaluation, then revaluation, the Second Sophistic was submitted to, according to inherently aesthetical and political arguments, quite similar to those with which one often criticises or defends literary, theatrical, or cinematographic post- 1 modernity. -

Perceptions of the Ancient Jews As a Nation in the Greek and Roman Worlds

Perceptions of the Ancient Jews as a Nation in the Greek and Roman Worlds By Keaton Arksey A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Classics University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2016 by Keaton Arksey Abstract The question of what made one Jewish in the ancient world remains a fraught topic for scholars. The current communis opinio is that Jewish communities had more in common with the Greeks and Romans than previously thought. Throughout the Diaspora, Jewish communities struggled with how to live amongst their Greco-Roman majority while continuing to practise their faith and thereby remain identifiably ‘Jewish’. To describe a unified Jewish identity in the Mediterranean in the period between 200 BCE and 200 CE is incorrect, since each Jewish community approached its identity in unique ways. These varied on the basis of time, place, and how the non-Jewish population reacted to the Jews and interpreted Judaism. This thesis examines the three major centres of Jewish life in the ancient world - Rome, Alexandria in Egypt, and Judaea - demonstrate that Jewish identity was remarkably and surprisingly fluid. By examining the available Jewish, Roman, and Greek literary and archaeological sources, one can learn how Jewish identity evolved in the Greco-Roman world. The Jews interacted with non-Jews daily, and adapted their neighbours’ practices while retaining what they considered a distinctive Jewish identity. Each chapter of this thesis examines a Jewish community in a different region of the ancient Mediterranean. -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-03398-6 - Man and Animal in Severan Rome: The Literary Imagination of Claudius Aelianus Steven D. Smith Index More information General index Achilles Tatius 5, 6, 31, 47, 49, 56, 95, 213, Atalante 10, 253, 254, 261, 262, 263, 265, 266, 265 267, 268 Aeneas 69, 92, 94, 95, 97 Atargatis 135 Aeschylus 91, 227 Athena 107, 125, 155 Aesop 6, 260 Athenaeus 47, 49, 58, 150, 207, 212, 254 aitnaios 108, 109, 181 Athenians 8, 16, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 41, 45, 58, akolasia 41, 43, 183, 279 77, 79, 109, 176, 199, 200, 202, 205, 206, 207, Alciphron 30, 33, 41, 45, 213 210, 227, 251, 252, 253 Alexander of Mundos 129 Athens 55, 60, 79 Alexander Severus 22, 72, 160, 216, 250, 251 Augustus 18, 75, 76, 77, 86, 98, 126, 139, 156, 161, Alexander the Great 58, 79, 109, 162, 165, 168, 170, 215, 216, 234, 238 170, 171, 177, 215, 217, 221, 241, 249 Aulus Gellius 47, 59, 203, 224, 229 Alexandria 23, 47, 48, 49, 149, 160, 162, 163, 164, Aurelian 127 168, 203 Anacreon 20 baboons 151 Androkles 81, 229, 230, 231, 232, 235, 236, 237, Bakhtin, Mikhail 136 247 Barthes, Roland 6 anthias 163, 164 bears 128, 191, 220, 234, 252, 261 ants 96, 250 bees 10, 33, 34, 36, 38, 45, 109, 113, 181, 186, 217, apes 181 218, 219, 220, 221, 222, 223, 224, 225, 242, 246 apheleia 20 beetles 14, 44 Aphrodite 34, 55, 122, 123, 125, 141, 150, 180, 207, Bhabha, Homi 85 210, 255, 256, 259, 260, 263, 267 boars 2, 40, 46, 250, 263 Apion 22, 118, 130, 149, 229, 231, 232 Brisson, Luc 194, 196 Apollo 38, 122, 123, 124, 125, 131, 140, 144, 155, 157, 175, 242, 272 -

Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-1992 Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance Leon Stratikis University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Stratikis, Leon, "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1992. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Leon Stratikis entitled "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Paul Barrette, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: James E. Shelton, Patrick Brady, Bryant Creel, Thomas Heffernan Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation by Leon Stratikis entitled Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. -

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

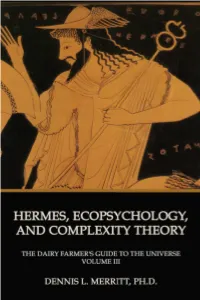

Hermes, Ecopsychology, and Complexity Theory

PSYCHOLOGY / JUNGIAN / ECOPSYCHOLOGY “Man today is painfully aware of the fact that neither his great religions nor his various philosophies seem to provide him with those powerful ideas that would give him the certainty and security he needs in face of the present condition of the world.” —C.G. Jung An exegesis of the myth of Hermes stealing Apollo’s cattle and the story of Hephaestus trapping Aphrodite and Ares in the act are used in The Dairy Farmer’s Guide to the Universe Volume III to set a mythic foundation for Jungian ecopsychology. Hermes, Ecopsychology, and Complexity Theory HERMES, ECOPSYCHOLOGY, AND illustrates Hermes as the archetypal link to our bodies, sexuality, the phallus, the feminine, and the earth. Hermes’ wand is presented as a symbol for COMPLEXITY THEORY ecopsychology. The appendices of this volume develop the argument for the application of complexity theory to key Jungian concepts, displacing classical Jungian constructs problematic to the scientific and academic community. Hermes is described as the god of complexity theory. The front cover is taken from an original photograph by the author of an ancient vase painting depicting Hermes and his wand. DENNIS L. MERRITT, Ph.D., is a Jungian psychoanalyst and ecopsychologist in private practice in Madison and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. A Diplomate of the C.G. Jung Institute of Analytical Psychology, Zurich, Switzerland, he also holds the following degrees: M.A. Humanistic Psychology-Clinical, Sonoma State University, California, Ph.D. Insect Pathology, University of California- Berkeley, M.S. and B.S. in Entomology, University of Wisconsin-Madison. He has participated in Lakota Sioux ceremonies for over twenty-five years which have strongly influenced his worldview. -

DIVINE TRIADS on an ARCHAIC ETRUSCAN FRIEZE PLAQUE from POGGIO CIVITATE (Murlo)

DIVINE TRIADS ON AN ARCHAIC ETRUSCAN FRIEZE PLAQUE FROM POGGIO CIVITATE (Murlo) (Con le taw. I-XII f. t.) On a wooded hill site near the citadel town of Murlo (1), some twenty-five kilometres south of Siena in the heart of Tuscany, excavation by Bryn Mawr College over the past four summers has uncovered a substantial complex of buildings together with a large quantity of architectural terracottas. The buildings, already presented elsewhere (2), date from the Archaic Etruscan period, about the middle of the sixth century B.C. The terracottas, of coarse (1) This study was originally given as part of a seminar on the material from Murlo at Bryn Mawr College in the Fall of 1968. I wish to thank Margaret George Butterworth for the drawing and for extensive ground work done on the frieze as a Senior honors thesis at Bryn Mawr in 1967-8. J. Penny Small, Docent Carl Eric Ostenberg, Professors Georges Dumézil, Einar Gjerstad, Erik Sjöqvist, and Doctor Guglielmo Maetzke, Soprintendente alle Antichità d’Etruria, Florence, were all kind enough to read or discuss various aspects of the paper and offered many useful criticisms and suggestions. Above all, I must record my gratitude to Professor Kyle Μ. Phillips, Jr. of Bryn Mawr College for the oppor- tunity to work with the material over the course of four summers at Murlo and for his unfailing help and guidance on this paper as classroom teacher, field in- structor, and friend. The opinions expressed, needless to say, are entirely my own responsibility. Study photographs of the Murlo friezes were taken by Göran Soderberg; final publication photographs are courtesy of the Florence Archaeolo- gical Museum, where the pieces, recently cleaned, were photographed by Ce- sare Mannucci. -

Pausanias' Description of Greece

BONN'S CLASSICAL LIBRARY. PAUSANIAS' DESCRIPTION OF GREECE. PAUSANIAS' TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH \VITTI NOTES AXD IXDEX BY ARTHUR RICHARD SHILLETO, M.A., Soiiii'tinie Scholar of Trinity L'olltge, Cambridge. VOLUME IT. " ni <le Fnusnnias cst un homme (jui ne mnnquo ni de bon sens inoins a st-s tlioux." hnniie t'oi. inais i}iii rn>it ou au voudrait croire ( 'HAMTAiiNT. : ftEOROE BELL AND SONS. YOUK STIIKKT. COVKNT (iAKDKX. 188t). CHISWICK PRESS \ C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT, CHANCEKV LANE. fA LC >. iV \Q V.2- CONTEXTS. PAGE Book VII. ACHAIA 1 VIII. ARCADIA .61 IX. BtEOTIA 151 -'19 X. PHOCIS . ERRATA. " " " Volume I. Page 8, line 37, for Atte read Attes." As vii. 17. 2<i. (Catullus' Aft is.) ' " Page 150, line '22, for Auxesias" read Anxesia." A.-> ii. 32. " " Page 165, lines 12, 17, 24, for Philhammon read " Philanimon.'' " " '' Page 191, line 4, for Tamagra read Tanagra." " " Pa ire 215, linu 35, for Ye now enter" read Enter ye now." ' " li I'aijf -J27, line 5, for the Little Iliad read The Little Iliad.'- " " " Page ^S9, line 18, for the Babylonians read Babylon.'' " 7 ' Volume II. Page 61, last line, for earth' read Earth." " Page 1)5, line 9, tor "Can-lira'" read Camirus." ' ; " " v 1'age 1 69, line 1 , for and read for. line 2, for "other kinds of flutes "read "other thites.'' ;< " " Page 201, line 9. for Lacenian read Laeonian." " " " line 10, for Chilon read Cliilo." As iii. 1H. Pago 264, " " ' Page 2G8, Note, for I iad read Iliad." PAUSANIAS. BOOK VII. ACIIAIA.