CHRIST CHURCH LIBRARY NEWSLETTER Volume 4, Issue 2 Hilary 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHRIST CHURCH LIBRARY NEWSLETTER Volume 12, Issue 1 2020 - 2021

CHRIST CHURCH LIBRARY NEWSLETTER Volume 12, Issue 1 2020 - 2021 ISSN 1756-6797 (Print), ISSN 1756-6800 (Online) The Salusbury Manuscripts: Notes on Provenance A Scarlatti Operatic Masterpiece Revisited MS 183 and MS 184 are two manuscripts which Among the many rare and precious holdings of belonged to the Salusbury family. They contain Christ Church Library, Oxford, is a manuscript of heraldry, and poems in Welsh and English, dating unusual importance in the history of music: Mus 989. from the turn of the sixteenth to the seventeenth It preserves a complete musical setting by composer century. Christ Church has no particular Welsh Alessandro Scarlatti of the text of poet Matteo Noris’ associations to explain why it should have been drama Il Flavio Cuniberto. given two manuscripts largely in the Welsh language. By many musicologists’ reckoning, Scarlatti was the The Salusbury family of Denbighshire is celebrated most important Italian opera composer of his time, in both codices. Members of that family were and a complete score of one of his operas is students at Oxford’s Jesus College and one at therefore a document of uncommon significance. Braesnose, in the sixteenth and seventeenth And although perhaps less well-known, Matteo Noris centuries. The two volumes arrived in Christ Church was a librettist of considerable importance. in the mid-eighteenth century but their donor is Historians of opera depend upon various kinds of unrecorded and it may be that the Library did not primary sources to write the performance history of quite know what to make of them. particular works in the repertory. -

Poikilia in the Book 4 of Alciphron's Letters

The Girlfriends’ Letters : Poikilia in the Book 4 of Alciphron’s Letters Michel Briand To cite this version: Michel Briand. The Girlfriends’ Letters : Poikilia in the Book 4 of Alciphron’s Letters. The Letters of Alciphron : To Be or not To be a Work ?, Jun 2016, Nice, France. hal-02522826 HAL Id: hal-02522826 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02522826 Submitted on 27 Mar 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THE GIRLFRIENDS’ LETTERS: POIKILIA IN THE BOOK 4 OF ALCIPHRON’S LETTERS Michel Briand Alciphron, an ambivalent post-modern Like Lucian of Samosata and other sophistic authors, as Longus or Achilles Tatius, Alciphron typically represents an ostensibly post-classical brand of literature and culture, which in many ways resembles our post- modernity, caught in permanent tension between virtuoso, ironic, critical, and distanced meta-fictionality, on the one hand, and a conscious taste for outspoken and humorous “bad taste”, Bakhtinian carnavalesque, social and moral margins, convoluted plots and sensational plays of immersion and derision, or realism and artificiality: the way Alciphron’s collection has been judged is related to the devaluation, then revaluation, the Second Sophistic was submitted to, according to inherently aesthetical and political arguments, quite similar to those with which one often criticises or defends literary, theatrical, or cinematographic post- 1 modernity. -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-03398-6 - Man and Animal in Severan Rome: The Literary Imagination of Claudius Aelianus Steven D. Smith Index More information General index Achilles Tatius 5, 6, 31, 47, 49, 56, 95, 213, Atalante 10, 253, 254, 261, 262, 263, 265, 266, 265 267, 268 Aeneas 69, 92, 94, 95, 97 Atargatis 135 Aeschylus 91, 227 Athena 107, 125, 155 Aesop 6, 260 Athenaeus 47, 49, 58, 150, 207, 212, 254 aitnaios 108, 109, 181 Athenians 8, 16, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 41, 45, 58, akolasia 41, 43, 183, 279 77, 79, 109, 176, 199, 200, 202, 205, 206, 207, Alciphron 30, 33, 41, 45, 213 210, 227, 251, 252, 253 Alexander of Mundos 129 Athens 55, 60, 79 Alexander Severus 22, 72, 160, 216, 250, 251 Augustus 18, 75, 76, 77, 86, 98, 126, 139, 156, 161, Alexander the Great 58, 79, 109, 162, 165, 168, 170, 215, 216, 234, 238 170, 171, 177, 215, 217, 221, 241, 249 Aulus Gellius 47, 59, 203, 224, 229 Alexandria 23, 47, 48, 49, 149, 160, 162, 163, 164, Aurelian 127 168, 203 Anacreon 20 baboons 151 Androkles 81, 229, 230, 231, 232, 235, 236, 237, Bakhtin, Mikhail 136 247 Barthes, Roland 6 anthias 163, 164 bears 128, 191, 220, 234, 252, 261 ants 96, 250 bees 10, 33, 34, 36, 38, 45, 109, 113, 181, 186, 217, apes 181 218, 219, 220, 221, 222, 223, 224, 225, 242, 246 apheleia 20 beetles 14, 44 Aphrodite 34, 55, 122, 123, 125, 141, 150, 180, 207, Bhabha, Homi 85 210, 255, 256, 259, 260, 263, 267 boars 2, 40, 46, 250, 263 Apion 22, 118, 130, 149, 229, 231, 232 Brisson, Luc 194, 196 Apollo 38, 122, 123, 124, 125, 131, 140, 144, 155, 157, 175, 242, 272 -

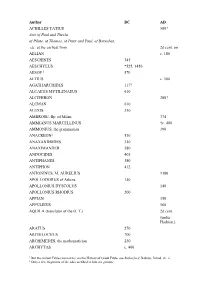

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SMATHERS LIBRARIES’ LATIN AND GREEK RARE BOOKS COLLECTION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS page LECTORI: TO THE READER ........................................................................................ 20 LATIN AUTHORS.......................................................................................................... 24 Ammianus ............................................................................................................... 24 Title: Rerum gestarum quae extant, libri XIV-XXXI. What exists of the Histories, books 14-31. ................................................................................. 24 Apuleius .................................................................................................................. 24 Title: Opera. Works. ......................................................................................... 24 Title: L. Apuleii Madaurensis Opera omnia quae exstant. All works of L. Apuleius of Madaurus which are extant. ....................................................... 25 See also PA6207 .A2 1825a ............................................................................ 26 Augustine ................................................................................................................ 26 Title: De Civitate Dei Libri XXII. 22 Books about the City of God. ..................... 26 Title: Commentarii in Omnes Divi Pauli Epistolas. Commentary on All the Letters of Saint Paul. .................................................................................... -

Contribution a L'histoire Intellectuelle De L'europe : Réseaux Du Livre

CONTRIBUTION A L’HISTOIRE INTELLECTUELLE DE L’EUROPE : RÉSEAUX DU LIVRE, RÉSEAUX DES LECTEURS Edité par Frédéric Barbier, István Monok L’Europe en réseaux Contribution à l’histoire de la culture écrite 1650–1918 Vernetztes Europa Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte des Buchwesens 1650–1918 Edité par / Herausgegeben von Frédéric Barbier, Marie-Elisabeth Ducreux, Matthias Middell, István Monok, Éva Ring, Martin Svatoš Volume IV Ecole pratique des hautes études, Paris Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris Centre des hautes études, Leipzig Centre européen d’histoire du livre de la Bibliothèque nationale Széchényi, Budapest CONTRIBUTION A L’HISTOIRE INTELLECTUELLE DE L’EUROPE : RÉSEAUX DU LIVRE, RÉSEAUX DES LECTEURS Edité par Frédéric Barbier, István Monok Országos Széchényi Könyvtár Budapest 2008 Les articles du présent volume correspondent aux Actes du colloque international organisé à Leipzig (Université de Leipzig, Zentrum für höhere Studien) en 2005, sur le thème « Netzwerke des Buchwesens : die Konstruktion Europas vom 15. bis zum 20. Jh. / Réseaux du livre, réseaux des lecteurs : la construction de l’Europe, XVe-XXe siècle ». Secrétariat scientifique Juliette Guilbaud (français) Wolfram Seidler (allemand) Graphiker György Fábián ISBN 978–963–200–550–8 ISBN 978–3–86583–269–6 © Országos Széchényi Könyvtár 1827 Budapest, Budavári palota F. épület Fax.: +36 1 37 56 167 [email protected] Leipziger Universitätsverlag GmbH, Leipzig Oststr. 41, D–04317 Leipzig Fax.: +49 341 99 00 440 [email protected] Table des matières Frédéric Barbier Avant-propos 7 Donatella Nebbiai Les réseaux de Matthias Corvin 17 Pierre Aquilon Précieux exemplaires Les éditions collectives des œuvres de Jean Gerson, 1483-1494 29 Juliette Guilbaud Das jansenistische Europa und das Buch im 17. -

Aristaenetus, Erotic Letters

ARISTAENETUS, EROTIC LETTERS Writings from the Greco-Roman World David Konstan and Johan C. Thom, General Editors Editorial Board Erich S. Gruen Wendy Mayer Margaret M. Mitchell Teresa Morgan Ilaria L. E. Ramelli Michael J. Roberts Karin Schlapbach James C. VanderKam L. Michael White Number 32 Volume Editor Patricia A. Rosenmeyer ARISTAENETUS, EROTIC LETTERS Introduced, translated and annotated by Peter Bing and Regina Höschele Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta ARISTAENETUS, EROTIC LETTERS Copyright © 2014 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aristaenetus, author. Erotic letters / Aristaenetus ; introduced, translated, and annotated by Peter Bing and Regina Höschele. pages cm. — (Writings from the Greco-Roman world ; volume 32) ISBN 978-1-58983-741-6 (paper binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-58983-742-3 (electronic format) — ISBN 978-1-58983-882-6 (hardcover binding : alk. paper) 1. Aristaenetus. Love epistles. I. Bing, Peter. II. Höschele, Regina. III. Aristaenetus. Love epistles. English. 2013. IV. Series: Writings from the Greco-Roman world ; v. 32. PA3874.A3E5 2013 880.8'.03538—dc23 2013024429 Printed on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence. -

Sex in the Ancient World from a to Z the Ancient World from a to Z

SEX IN THE ANCIENT WORLD FROM A TO Z THE ANCIENT WORLD FROM A TO Z What were the ancient fashions in men’s shoes? How did you cook a tunny or spice a dormouse? What was the daily wage of a Syracusan builder? What did Romans use for contraception? This new Routledge series will provide the answers to such questions, which are often overlooked by standard reference works. Volumes will cover key topics in ancient culture and society—from food, sex and sport to money, dress and domestic life. Each author will be an acknowledged expert in their field, offering readers vivid, immediate and academically sound insights into the fascinating details of daily life in antiquity. The main focus will be on Greece and Rome, though some volumes will also encompass Egypt and the Near East. The series will be suitable both as background for those studying classical subjects and as enjoyable reading for anyone with an interest in the ancient world. Already published: Food in the Ancient World from A to Z Andrew Dalby Sport in the Ancient World from A to Z Mark Golden Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z John G.Younger Forthcoming titles: Birds in the Ancient World from A to Z Geoffrey Arnott Money in the Ancient World from A to Z Andrew Meadows Domestic Life in the Ancient World from A to Z Ruth Westgate and Kate Gilliver Dress in the Ancient World from A to Z Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones et al. SEX IN THE ANCIENT WORLD FROM A TO Z John G.Younger LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave., New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2006. -

Persuasion, Emotion, and the Letters of the Alexander Romance

Persuasion, Emotion, and the Letters of the Alexander Romance JACQUELINE ARTHUR-MONTAGNE Stanford University Mixture is the letter, the epistle which is not a genre, but all genres, literature itself. Jacques Derrida, The Postcard (48) The presence of over thirty letters embedded in the Greek Alexander Romance has garnered frequent attention from scholars of epistolography, novels, and fiction.1 These letters are widely distributed throughout the three books of the Romance, attributed to various characters in the plot. What is most striking about the deployment of letters in the narrative is the mixture of different epis- tolographical types. From battle briefs, boastful barbarian epistles, and lengthy letters of marvels, it is clear that the epistolary frame here operates in very different capacities. I know of no other work of ancient fiction that in- corporates so many different epistolary forms. If it is fair to regard epistolog- raphy as a spectrum of genres,2 then the Alexander Romance spans the full register from functional to philosophical. Sorting the sources and interrelationships of these letters has been a chal- lenge for critics, further complicated by the tangled transmission history and the multiple recensions of the Alexander Romance. Reinhold Merkelbach’s seminal study in 1954 made a crucial and intuitive distinction between the lengthy ‘Wunderbriefe’ and the novel’s shorter letters: he claimed that the lat- ter category represents the remnants of a lost epistolary novel about the life of ————— 1 Hägg 1983, 126 regards the incorporation of letters as the ‘most important innovation’ on the part of the author. For the most recent treatments, see Konstan 1998, Rosenmeyer 2001 (ch. -

Loeb Classical Library

LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY 2015 Founded by JAMES LOEB 1911 Edited by JEFFREY HENDERSON DIGITAL LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY For information about digital Loeb Classical Library access plans or to register for an institutional free trial, visit www.loebclassics.com Winner, PROSE Award for Best Humanities eProduct, Association of American Publishers “For the last couple of decades, the Loeb Library has been undergoing a renaissance. There are new or revised translations of many authors, and, a month or two back, the entire library was brought online at loebclassics.com. There are other searchable classics databases … Yet there is still something glorious about having all 500-plus Loebs online … It’s an extraordinary resource.” —ROGER KIMBALL, NEW CRITERION “The Loeb Library … remains to this day the Anglophone world’s most readily accessible collection of classical masterpieces … Now, with their digitization, [the translations] have crossed yet another frontier.” —WALL STREET JOURNAL The mission of the Loeb Classical Library, founded by James Loeb in 1911, has always been to make Classical Greek and Latin literature accessible to the broadest range of readers. The digital Loeb Classical Library extends this mission into the twenty-first century. Harvard University Press is honored to renew James Loeb’s vision of accessibility and to present an interconnected, fully searchable, perpetually growing, virtual library of all that is important in Greek and Latin literature. e Single- and dual-language reading modes e Sophisticated Bookmarking and Annotation features e Tools for sharing Bookmarks and Annotations e User account and My Loeb content saved in perpetuity e Greek keyboard e Intuitive Search and Browse e Includes every Loeb volume in print e New volumes uploaded regularly www.loebclassics.com also available in theNEW i tatti TITLES renaissance library THEOCRITUS. -

Menander's Characters in the Fourth Century BC and Their Reception in Modern Greek Theatre

Menandrean Characters in Context: Menander’s Characters in the fourth century BC and their reception in Modern Greek Theatre. Stavroula Kiritsi Royal Holloway, University of London PhD in Classics 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Stavroula Kiritsi, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______Stavroula Kiritsi________________ Date: _________27/06/2017_______________ 2 Abstract The thesis explores the way in which character is represented in Menander’s comedies and in the revival, translation, and reception of Menandrean comedy in the modern Greek theatre. Although modern translators and directors may have sought to reproduce the ancient dramas faithfully, they inevitably reshaped and reinterpreted them to conform to audience expectations and the new cultural context. Comparing aspects of character in the ancient and modern plays sheds light on both traditions. In assessing how character was conceived in the Hellenistic period, I make use of ethical works by Aristotle and other philosophers, which provide an appropriate vocabulary for identifying the assumptions of Menander and his audience. For the modern adaptations, I have made extensive use of a variety of archival materials as well as interviews with artists engaged at every stage of the production. The thesis comprises an Introduction, two Parts (I-II), and Conclusion. Part I examines Menandrean characters in the context of the Hellenistic Greek audience and society, with special reference to Aristotle’s and Theophrastus’ accounts of character and emotion. In the first chapter of Part II I survey the ‘loss and survival’ of Menander from antiquity and Hellenistic times, through Byzantium and the post-Byzantine period, to nineteenth-century Greece. -

The Characters of Theophrastus, Newly Edited and Translated by J.M

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY EDITED BY T. E. PAGE, LITl-.D. E. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. W. H. D. ROUSE, i.ttt.d. THE CHARACTERS OF THEOPHRASTUS HERODES, CERCIDAS, AND THE GREEK CHOLIAMBIC POETS (except callimachus and babrius) THE CHARACTEKS OF THEOPHRASTUS NEWLY EDITED AND TRANSLATED J. M. EDMONDS LATE FELLOW OF JESUS COLLEGE LECTURER IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE LONDON: WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD NEW YORK: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS MCMXXIX PA PREFACE The Characters of Theophrastus are a good wine that needs no bush, but it has been bottled anew, and new bottles may need a word of recommendation. The mere existence of an early English translation such as Healey's would hardly justify an archaistic rendering, but the Character, in the hands of Hall, Overbury, and Earle, has become a native genre, and that, I think, is enough to make such a rendering the most palatable. And this style of translation, taunts of ' Wardour Street ' notwithstanding, has a great advantage. Greek, being itself simple, goes best into a simple style of English ; and in the seventeenth century it was still easy to put things simply without making them bald. A simple trans- lation into our modern dialect, if it is to rise above Translator's English, is always difficult and often unattainable. In preparing the text I have discarded rfluch of my earlier work, in the belief, shared no doubt by many scholars, that the discovery of papyrus frag- ments of ancient Greek books has shifted the editor's PREFACE bearings from Constantinople to Alexandria. With the ' doctrine of the normal line,' exploded by A.