Pandemic, Human Precarity and Post-Pandemic Metaverses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This Copy of the Thesis Has Been

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2012 Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman Vita-More, Natasha http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/1182 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognize that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. 1 Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman by NATASHA VITA-MORE A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfillment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Art & Media Faculty of Arts April 2012 2 Natasha Vita-More Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman The thesis’ study of life expansion proposes a framework for artistic, design-based approaches concerned with prolonging human life and sustaining personal identity. To delineate the topic: life expansion means increasing the length of time a person is alive and diversifying the matter in which a person exists. -

Humana.Mente Complete Issue 26.Pdf

EDITORIAL MANAGER: DUCCIO MANETTI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE Editorial EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: SILVANO ZIPOLI CAIANI - UNIVERSITY OF MILAN VICE DIRECTOR: MARCO FENICI - UNIVERSITY OF SIENA Board INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL BOARD JOHN BELL - UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO GIOVANNI BONIOLO - INSTITUTE OF MOLECULAR ONCOLOGY FOUNDATION MARIA LUISA DALLA CHIARA - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE DIMITRI D'ANDREA - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE BERNARDINO FANTINI - UNIVERSITÉ DE GENÈVE LUCIANO FLORIDI - UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD MASSIMO INGUSCIO - EUROPEAN LABORATORY FOR NON-LINEAR SPECTROSCOPY GEORGE LAKOFF - UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY PAOLO PARRINI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE ALBERTO PERUZZI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE JEAN PETITOT - CREA, CENTRE DE RECHERCHE EN ÉPISTÉMOLOGIE APPLIQUÉE CORRADO SINIGAGLIA - UNIVERSITY OF MILAN BAS C. VAN FRAASSEN - SAN FRANCISCO STATE UNIVERSITY CONSULTING EDITORS CARLO GABBANI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE ROBERTA LANFREDINI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE MARCO SALUCCI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE ELENA ACUTI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE MATTEO BORRI - UNIVERSITÉ DE GENÈVE ROBERTO CIUNI - UNIVERSITY OF DELFT Editorial SCILLA BELLUCCI, LAURA BERITELLI, RICCARDO FURI, ALICE GIULIANI, STEFANO LICCIOLI, UMBERTO MAIONCHI Staff HUMANA.MENTE - QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Fiorella Battaglia, Antonio Carnevale Epistemological and Moral Problems with Human Enhancement III PAPERS Volker Gerhardt Technology as a Medium of Ethics and Culture 1 Nikil Mukerji, Julian Nida-Rümelin Towards a Moderate Stance on Human Enhancement 17 Christopher -

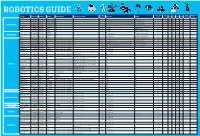

Robotics Section Guide for Web.Indd

ROBOTICS GUIDE Soldering Teachers Notes Early Higher Hobby/Home The Robot Product Code Description The Brand Assembly Required Tools That May Be Helpful Devices Req Software KS1 KS2 KS3 KS4 Required Available Years Education School VEX 123! 70-6250 CLICK HERE VEX No ✘ None No ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Dot 70-1101 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Dash 70-1100 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ready to Go Robot Cue 70-1108 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Codey Rocky 75-0516 CLICK HERE Makeblock No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloadb ale Mblock Software ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ozobot 70-8200 CLICK HERE Ozobot No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ohbot 76-0000 CLICK HERE Ohbot No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads for Windows or Pi ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ SoftBank NAO 70-8893 CLICK HERE No ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Choregraph - free to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Robotics Humanoid Robots SoftBank Pepper 70-8870 CLICK HERE No ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Choregraph - free to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Robotics Ohbot 76-0001 CLICK HERE Ohbot Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads for Windows or Pi ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ FABLE 00-0408 CLICK HERE Shape Robotics Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Free Downloadable ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ VEX GO! 70-6311 CLICK HERE VEX Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ Windows, Mac, -

149-Page PDF Version

By Bradford Hatcher © 2019 Bradford Hatcher ISBN: 978-0-9824191-8-2 Download at: https://www.hermetica.info/Intervention.html or: https://www.hermetica.info/Intervention.pdf Cover Photo Credit: Found online. Appears to be a conception of an evolved Terran reptilian life form. Table of Contents Part One 5 Preface 5 Puppet Shows 7 Waldo Speaking, Part 1 11 Waldo Speaking, Part 2 17 Wilma Speaks of Spirit 24 The Eck 30 Gizmos and the Van 34 Growing Up Van 42 Some Changes are Made 49 Culling Homo Non Grata 56 Introducing the Ta 63 Terrestrial and Aquatic Ta 67 Vestan, Myco, and Raptor Ta 72 Part Two 78 Progress Report at I+20 78 Desert Colonies 80 The Final Frontier, For Now 85 The Stellar Fleet 89 Remembering Community 94 Prototypes and Lexicons 99 For the Kids 104 Cultural Evolution 112 Cultural Engineering 119 Bioengineering 124 The Commons 128 The Tour 132 Mitakuye Oyasin 137 A Partial Glossary 147 Part One It gives one a feeling of confidence to see nature still busy with experiments, still dynamic, and not through nor satisfied because a Devonian fish managed to end as a two-legged character with a straw hat. There are other things brewing and growing in the oceanic vat. It pays to know this. It pays to know that there is just as much future as there is past. The only thing that doesn't pay is to be sure of man's own part in it. There are things down there still coming ashore. Never make the mistake of thinking life is now adjusted for eternity. -

Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile

FETISHISM AND THE CULTURE OF THE AUTOMOBILE James Duncan Mackintosh B.A.(hons.), Simon Fraser University, 1985 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Communication Q~amesMackintosh 1990 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1990 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : James Duncan Mackintosh DEGREE : Master of Arts (Communication) TITLE OF THESIS: Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chairman : Dr. William D. Richards, Jr. \ -1 Dr. Martih Labbu Associate Professor Senior Supervisor Dr. Alison C.M. Beale Assistant Professor \I I Dr. - Jerry Zqlove, Associate Professor, Department of ~n~lish, External Examiner DATE APPROVED : 20 August 1990 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Dissertation: Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile. Author : -re James Duncan Mackintosh name 20 August 1990 date ABSTRACT This thesis explores the notion of fetishism as an appropriate instrument of cultural criticism to investigate the rites and rituals surrounding the automobile. -

Philosophical Posthumanism and Its Others

Ph.D. Dissertation The Posthuman: Philosophical Posthumanism and Its Others Ph.D. Candidate Francesca Ferrando Program Ph.D. in Philosophy and Theory of Human Sciences Università di Roma Tre 1 INDEX Introduction From Humans to Posthumans p. 11 1. Part 1 Philosophical Posthumanism and Its Others pp. 21-123 (What is Philosophical Posthumanism?) 1. Premises - the Politics of the “Post” p. 22 2. From Postmodern to Posthuman p. 25 3. Posthumanism and Its Others p. 30 4. Transhumanism and Techno-Reductionism p. 31 5. Posthuman Technologies p. 38 6. Antihumanism and The Übermensch 2 p. 44 7. Philosophical Posthumanism p. 49 (Of Which “Human” is the Posthuman a “Post”?) 8. The Semantics of the Post-Human p. 55 9. Humanizing p. 56 10. The Anthropological Machine p. 60 11. More or Less, Human p. 65 12. Technologies of the Self as Posthuman (Re)Sources p. 70 13. When and How did Humans become Human? p. 74 14. Humanitas p. 76 15. Homo sapiens 3 p. 79 (Have We Always Been Posthuman?) 16. Posthuman Life p. 84 a. Animate / Inanimate p. 84 b. Bios and Zoe p. 86 c. Artificial Life p. 88 17. Autopoiesis p. 91 18. Posthumanism is a Perspectivism p. 98 19. Evolving Species p. 19 20. Posthumanities p. 108 4 21. The Posthuman as New Materialisms p. 114 22. Vibrating Matter p. 120 23. The Posthuman Ontological Multiverse p. 124 2. Part 2 Philosophical Reflections on Empirical Data pp. 137-150 Is The Post-Human A Post-Woman? Robots, Cyborgs, Artificial Intelligence and the Futures of Gender: A Case Study 1. -

2016-2017 Report

The Society of Fellows in the Humanities Annual Report 2016–2017 Society of Fellows Mail Code 5700 Columbia University 2960 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Phone: (212) 854-8443 Fax: (212) 662-7289 [email protected] www.societyoffellows.columbia.edu By FedEx or UPS: Society of Fellows 74 Morningside Drive Heyman Center, First Floor East Campus Residential Center Columbia University New York, NY 10027 Posters courtesy of designers Amelia Saul and Sean Boggs 2 Contents Report From The Chair 5 Special Events 31 Members of the 2016–2017 Governing Board 8 Heyman Center Events 35 • Event Highlights 36 Forty-Second Annual Fellowship Competition 9 • Public Humanities Initiative 47 Fellows in Residence 2016–2017 11 • Heyman Center Series and Workshops 50 • Benjamin Breen 12 Nietzsche 13/13 Seminar 50 • Christopher M. Florio 13 New Books in the Arts & Sciences 50 • David Gutkin 14 New Books in the Society of Fellows 54 • Heidi Hausse 15 The Program in World Philology 56 • Arden Hegele 16 • Full List of Heyman Center Events • Whitney Laemmli 17 2016–2017 57 • Max Mishler 18 • María González Pendás 19 Heyman Center Fellows 2016–2017 65 • Carmel Raz 20 Alumni Fellows News 71 Thursday Lectures Series 21 Alumni Fellows Directory 74 • Fall 2016: Fellows’ Talks 23 • Spring 2017: Shock and Reverberation 26 2016–2017 Fellows at the annual year-end Spring gathering (from left): María González Pendás (2016–2019), Arden Hegele (2016–2019), David Gutkin (2015–2017), Whitney Laemmli (2016–2019), Christopher Florio (2016–2019) Heidi Hausse (2016–2018), Max Mishler (2016–2017), and Carmel Raz (2015–2018). -

Where's My Jet Pack?

Where's My Jet Pack? Online Communication Practices and Media Frames of the Emergent Voluntary Cyborg Subculture By Tamara Banbury A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Legal Studies Faculty of Public Affairs Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2019 Tamara Banbury Abstract Voluntary cyborgs embed technology into their bodies for purposes of enhancement or augmentation. These voluntary cyborgs gather in online forums and are negotiating the elements of subculture formation with varying degrees of success. The voluntary cyborg community is unusual in subculture studies due to the desire for mainstream acceptance and widespread adoption of their practices. How voluntary cyborg practices are framed in media articles can affect how cyborgian practices are viewed and ultimately, accepted or denied by those outside the voluntary cyborg subculture. Key Words: cyborg, subculture, implants, community, technology, subdermal, chips, media frames, online forums, voluntary ii Acknowledgements The process of researching and writing a thesis is not a solo endeavour, no matter how much it may feel that way at times. This thesis is no exception and if it weren’t for the advice, feedback, and support from a number of people, this thesis would still just be a dream and not a reality. I want to acknowledge the institutions and the people at those institutions who have helped fund my research over the last year — I was honoured to receive one of the coveted Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholarships for master’s students from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. -

PROTOTYPE for QUADRUPED ROBOT USING Iot to DELIVER MEDICINES and ESSENTIALS to COVID-19 PATIENT

International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology (IJARET) 4Volume 12, Issue 5, May 2021, pp. 147-155, Article ID: IJARET_12_05_014 Available online at https://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJARET?Volume=12&Issue=5 ISSN Print: 0976-6480 and ISSN Online: 0976-6499 DOI: 10.34218/IJARET.12.5.2021.014 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed PROTOTYPE FOR QUADRUPED ROBOT USING IoT TO DELIVER MEDICINES AND ESSENTIALS TO COVID-19 PATIENT Anita Chaudhari, Jeet Thakur and Pratiksha Mhatre Department of Information Technology, St. John College of Engineering and Management, Palghar, Maharashtra, India ABSTRACT The Wheeled robots cannot work properly on the rocky surface or uneven surface. They consume a lot of power and struggle when they go on rocky surface. To tackle the disadvantages of wheeled robot we replaced the wheels like shaped legs with the spider legs or spider arms. Quadruped robot has complicated moving patterns and it can also move on surfaces where wheeled shaped robots would fail. They can easily walk on rocky or uneven surface. The main purpose of the project is to develop a consistent platform that enables the implementation of steady and fast static/dynamic walking on ground/Platform to deliver medicines to covid-19 patients. The main advantage of spider robot also called as quadruped robot is that it is Bluetooth controlled robot, through the android application, we can control robot from anywhere; it avoids the obstacle using ultrasonic sensor. Key words: Bluetooth module, Quadruped, Rough-terrain robots. Cite this Article: Anita Chaudhari, Jeet Thakur and Pratiksha Mhatre, Prototype for Quadruped Robot using IoT to Deliver Medicines and Essentials to Covid-19 Patient, International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology, 12(5), 2021, pp. -

Service Robots 7 Mouser Staff

1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome from the Editor 3 Deborah S. Ray Foreword 6 Grant Imahara Introduction to Service Robots 7 Mouser Staff Sanbot Max: Anatomy of a Service Robot 11 Steven Keeping CIMON Says: Design Lessons from a Robot Assistant in Space 17 Traci Browne 21 Revisiting the Uncanny Valley Jon Gabay Robotic Hands Strive for Human Capabilities 25 Bill Schweber Robotic Gesturing Meets Sign Language 30 Bill Schweber Mouser and Mouser Electronics are registered trademarks of Mouser Electronics, Inc. Other products, logos, and company names mentioned herein may be trademarks of their respective owners. Reference designs, conceptual illustrations, and other graphics included herein are for informational purposes only. Copyright © 2018 Mouser Electronics, Inc. – A TTI and Berkshire Hathaway company. 2 WELCOME FROM THE EDITOR If you’re just now joining us for favorite robots from our favorite This eBook accompanies EIT Video Mouser’s 2018 Empowering shows and movies: Star Wars, Star #3, which features the Henn na Innovation Together™ (EIT) program, Trek, Lost in Space, and Dr. Who. Hotel, the world’s first hotel staffed welcome! This year’s EIT program— by robots. Geared toward efficiency Generation Robot—explores robotics In this EIT segment, we explore and customer comfort, these robots as a technology capable of impacting service robots, which combine not only provide an extraordinary and changing our lives in the 21st principles of automation with that experience of efficiency and comfort, century much like the automobile of robotics to assist humans with but also a fascinating and heart- impacted the 20th century and tasks that are dirty, dangerous, heavy, warming experience for guests. -

Sviluppo Di Un'app Android Per Il Robot Sanbot

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Matematica "Tullio Levi-Civita" Corso di Laurea in Informatica Sviluppo di un’app Android per il robot Sanbot Tesi di laurea triennale Relatore Prof. Mauro Conti Laureando Nicolae Andrei Tabacariu Anno Accademico 2017-2018 Nicolae Andrei Tabacariu: Sviluppo di un’app Android per il robot Sanbot, Tesi di laurea triennale, c Settembre 2018. “Life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated” — Confucius Ringraziamenti Innanzitutto, vorrei esprimere la mia gratitudine al Prof. Mauro Conti, relatore della mia tesi, per l’aiuto e il sostegno fornitomi durante l’attività di stage e la stesura del presente documento. Desidero ringraziare con affetto la mia famiglia e la mia ragazza Erica, che mi hanno sostenuto economicamente ed emotivamente in questi anni di studio, senza i quali probabilmente non sarei mai arrivato alla fine di questo percorso. Desidero poi ringraziare gli amici e i compagni che mi hanno accompagnato in questi anni e che mi hanno dato sostegno ed affetto. Infine porgo i miei ringraziamenti a tutti i componenti di Omitech S.r.l. per l’opportunità di lavorare con loro, per il rispetto e la cordialità con cui mi hanno trattato. Padova, Settembre 2018 Nicolae Andrei Tabacariu iii Indice 1 Introduzione1 1.1 L’azienda . .1 1.2 Il progetto di stage . .2 1.3 Organizzazione dei contenuti . .2 2 Descrizione dello stage3 2.1 Il progetto di stage . .3 2.1.1 Analisi dei rischi . .4 2.1.2 Obiettivi fissati . .4 2.1.3 Pianificazione del lavoro . .5 2.1.4 Interazione con i tutor . -

321444 1 En Bookbackmatter 533..564

Index 1 Abdominal aortic aneurysm, 123 10,000 Year Clock, 126 Abraham, 55, 92, 122 127.0.0.1, 100 Abrahamic religion, 53, 71, 73 Abundance, 483 2 Academy award, 80, 94 2001: A Space Odyssey, 154, 493 Academy of Philadelphia, 30 2004 Vital Progress Summit, 482 Accelerated Math, 385 2008 U.S. Presidential Election, 257 Access point, 306 2011 Egyptian revolution, 35 ACE. See artificial conversational entity 2011 State of the Union Address, 4 Acquired immune deficiency syndrome, 135, 2012 Black Hat security conference, 27 156 2012 U.S. Presidential Election, 257 Acxiom, 244 2014 Lok Sabha election, 256 Adam, 57, 121, 122 2016 Google I/O, 13, 155 Adams, Douglas, 95, 169 2016 State of the Union, 28 Adam Smith Institute, 493 2045 Initiative, 167 ADD. See Attention-Deficit Disorder 24 (TV Series), 66 Ad extension, 230 2M Companies, 118 Ad group, 219 Adiabatic quantum optimization, 170 3 Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi, 21 3D bioprinting, 152 Adobe, 30 3M Cloud Library, 327 Adonis, 84 Adultery, 85, 89 4 Advanced Research Projects Agency Network, 401K, 57 38 42, 169 Advice to a Young Tradesman, 128 42-line Bible, 169 Adwaita, 131 AdWords campaign, 214 6 Affordable Care Act, 140 68th Street School, 358 Afghan Peace Volunteers, 22 Africa, 20 9 AGI. See Artificial General Intelligence 9/11 terrorist attacks, 69 Aging, 153 Aging disease, 118 A Aging process, 131 Aalborg University, 89 Agora (film), 65 Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, 135 Agriculture, 402 AbbVie, 118 Ahmad, Wasil, 66 ABC 20/20, 79 AI. See artificial intelligence © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016 533 N.