The Assad Regime's Propaganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country of Origin Information Report Syria June 2021

Country of origin information report Syria June 2021 Page 1 of 102 Country of origin information report Syria | June 2021 Publication details City The Hague Assembled by Country of Origin Information Reports Section (DAF/AB) Disclaimer: The Dutch version of this report is leading. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands cannot be held accountable for misinterpretations based on the English version of the report. Page 2 of 102 Country of origin information report Syria | June 2021 Table of contents Publication details ............................................................................................2 Table of contents ..........................................................................................3 Introduction ....................................................................................................5 1 Political and security situation .................................................................... 6 1.1 Political and administrative developments ...........................................................6 1.1.1 Government-held areas ....................................................................................6 1.1.2 Areas not under government control. ............................................................... 11 1.1.3 COVID-19 ..................................................................................................... 13 1.2 Armed groups ............................................................................................... 13 1.2.1 Government forces ....................................................................................... -

Syria and Repealing Decision 2011/782/CFSP

30.11.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 330/21 DECISIONS COUNCIL DECISION 2012/739/CFSP of 29 November 2012 concerning restrictive measures against Syria and repealing Decision 2011/782/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, internal repression or for the manufacture and maintenance of products which could be used for internal repression, to Syria by nationals of Member States or from the territories of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in Member States or using their flag vessels or aircraft, shall be particular Article 29 thereof, prohibited, whether originating or not in their territories. Whereas: The Union shall take the necessary measures in order to determine the relevant items to be covered by this paragraph. (1) On 1 December 2011, the Council adopted Decision 2011/782/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Syria ( 1 ). 3. It shall be prohibited to: (2) On the basis of a review of Decision 2011/782/CFSP, the (a) provide, directly or indirectly, technical assistance, brokering Council has concluded that the restrictive measures services or other services related to the items referred to in should be renewed until 1 March 2013. paragraphs 1 and 2 or related to the provision, manu facture, maintenance and use of such items, to any natural or legal person, entity or body in, or for use in, (3) Furthermore, it is necessary to update the list of persons Syria; and entities subject to restrictive measures as set out in Annex I to Decision 2011/782/CFSP. (b) provide, directly or indirectly, financing or financial assistance related to the items referred to in paragraphs 1 (4) For the sake of clarity, the measures imposed under and 2, including in particular grants, loans and export credit Decision 2011/273/CFSP should be integrated into a insurance, as well as insurance and reinsurance, for any sale, single legal instrument. -

Officials Say Flynn Discussed Sanctions

Officials say Flynn discussed sanctions The Washington Post February 10, 2017 Friday, Met 2 Edition Copyright 2017 The Washington Post All Rights Reserved Distribution: Every Zone Section: A-SECTION; Pg. A08 Length: 1971 words Byline: Greg Miller;Adam Entous;Ellen Nakashima Body Talks with Russia envoy said to have occurred before Trump took office National security adviser Michael Flynn privately discussed U.S. sanctions against Russia with that country's ambassador to the United States during the month before President Trump took office, contrary to public assertions by Trump officials, current and former U.S. officials said. Flynn's communications with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak were interpreted by some senior U.S. officials as an inappropriate and potentially illegal signal to the Kremlin that it could expect a reprieve from sanctions that were being imposed by the Obama administration in late December to punish Russia for its alleged interference in the 2016 election. Flynn on Wednesday denied that he had discussed sanctions with Kislyak. Asked in an interview whether he had ever done so, he twice said, "No." On Thursday, Flynn, through his spokesman, backed away from the denial. The spokesman said Flynn "indicated that while he had no recollection of discussing sanctions, he couldn't be certain that the topic never came up." Officials said this week that the FBI is continuing to examine Flynn's communications with Kislyak. Several officials emphasized that while sanctions were discussed, they did not see evidence that Flynn had an intent to convey an explicit promise to take action after the inauguration. Flynn's contacts with the ambassador attracted attention within the Obama administration because of the timing. -

Revolutions in the Arab World Political, Social and Humanitarian Aspects

REPORT PREPARED WITHIN FRAMEWORK OF THE PROJECT EXPANSION OF THE LIBRARY OF COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT, CO-FUNDED BY EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND REVOLUTIONS IN THE ARAB WORLD POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND HUMANITARIAN ASPECTS RADOSŁAW BANIA, MARTA WOŹNIAK, KRZYSZTOF ZDULSKI OCTOBER 2011 COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT OFFICE FOR FOREIGNERS, POLAND DECEMBER 2011 EUROPEJSKI FUNDUSZ NA RZECZ UCHODŹCÓW REPORT PREPARED WITHIN FRAMEWORK OF THE PROJECT EXPANSION OF THE LIBRARY OF COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT, CO-FUNDED BY EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND REVOLUTIONS IN THE ARAB WORLD POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND HUMANITARIAN ASPECTS RADOSŁAW BANIA, MARTA WOŹNIAK, KRZYSZTOF ZDULSKI COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT OFFICE FOR FOREIGNERS, POLAND OCTOBER 2011 EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND Revolutions in the Arab World – Political, Social and Humanitarian Aspects Country of Origin Information Unit, Office for Foreigners, 2011 Disclaimer The report at hand is a public document. It has been prepared within the framework of the project “Expansion of the library of Country of Origin Information Unit” no 1/7/2009/EFU, co- funded by the European Refugee Fund. Within the framework of the above mentioned project, COI Unit of the Office for Foreigners commissions reports made by external experts, which present detailed analysis of problems/subjects encountered during refugee/asylum procedures. Information included in these reports originates mainly from publicly available sources, such as monographs published by international, national or non-governmental organizations, press articles and/or different types of Internet materials. In some cases information is based also on experts’ research fieldworks. All the information provided in the report has been researched and evaluated with utmost care. -

The Degrading of Syria's Regime | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Interviews and Presentations The Degrading of Syria's Regime by Andrew J. Tabler Jun 15, 2011 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Andrew J. Tabler Andrew J. Tabler is the Martin J. Gross fellow in the Geduld Program on Arab Politics at The Washington Institute, where he focuses on Syria and U.S. policy in the Levant. A n Interview by Bernard Gwertzman, CFR.org The Obama administration believes that the regime of President Bashar al-Assad of Syria is now in a "downward trajectory" because of the violence against its own people and the failure to undertake reforms, says Andrew J. Tabler, a former journalist in Syria. But the regime's decline also poses new hurdles for U.S. efforts to engage Syria, break its ties with Iran, and promote peace with Israel, he says. Because of the Internet and some loosening of ties with foreign countries, the "genie is out of the bottle," he says. "The problem with the Assad regime is that the genie is now just way too big for the bottle." He says unlike Tunisia and Egypt, where the army helped overthrow the leader, the security forces in Syria will remain loyal to Assad. Any change will be the result of Sunnis, who comprise the majority of the population, taking over from the Alawites led by Assad. GWERTZMAN: With the violent crackdowns in Syria lately and the statements of condemnation from Washington, does this wreck whatever chance there was for an early U.S.-Syrian rapprochement? TABLER: Yes it does, and for the foreseeable future. -

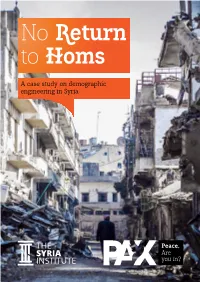

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

Pdf (2012 年 7 月 29 日にアクセス)

2014年 2 月 The 1st volume 【編集ボード】 委員長: 鈴木均 内部委員: 土屋一樹、齋藤純、ダルウィッシュ ホサム、石黒大岳、 渡邊祥子、福田安志 外部委員: 内藤正典 本誌に掲載されている論文などの内容や意見は、外部からの論稿を含め、執筆者 個人に属すものであり、日本貿易振興機構あるいはアジア経済研究所の公式見解を 示すものではありません。 中東レビュー 第 1 号 2014 年 2 月 28 日発行© 編集: 『中東レビュー』編集ボード 発行: アジア経済研究所 独立行政法人日本貿易振興機構 〒261-8545 千葉県千葉市美浜区若葉 3-2-2 URL: http://www.ide.go.jp/Japanese/Publish/Periodicals/Me_review/ ISSN: 2188-4595 ウェブ雑誌『中東レビュー』の創刊にあたって 日本貿易振興機構アジア経済研究所では 2011 年初頭に始まったいわゆる「アラブの春」と その後の中東地域の政治的変動に対応して、これまで国際シンポジウムや政策提言研究、アジ 研フォーラムなどさまざまな形で研究成果の発信と新たな研究ネットワークの形成に取り組ん できた。今回、中東地域に関するウェブ雑誌『中東レビュー』を新たな構想と装いのもとで創 刊しようとするのも、こうした取り組みの一環である。 当研究所は 1975 年 9 月刊行の『中東総合研究』第 1 号以来、中東地域に関する研究成果を 定期的に刊行される雑誌の形態で公開・提供してきた。1986 年 9 月以降は『現代の中東』およ び『中東レビュー』として年 2 回の刊行を重ねてきたが、諸般の事情により『現代の中東』は 2010 年 1 月刊行の第 48 号をもって休刊している。『中東レビュー』はこれらの過去の成果を 直接・間接に継承し、新たな環境のもとでさらに展開させていこうと企図するものである。 今回、不定期刊行のウェブ雑誌『中東レビュー』を新たに企画するにあたり、そのひとつの 核として位置づけているのが「中東政治経済レポート」の連載である。「中東政治経済レポート」 はアジ研の中東関係の若手研究者を中心に、担当する国・地域の政治・経済および社会について の情勢レポートを随時ウェブ発信し、これを年に一度再編集して年次レポートとして継続的に 提供していく予定である。 『中東レビュー』のもうひとつの核は、変動しつつある現代中東を対象とした社会科学的な 論稿の掲載である。論稿についても随時ウェブサイトに掲載していくことで、執筆から発表ま でのタイムラグを短縮し、かつこれを『中東レビュー』の総集編に収録する段階で最終的にテ キストを確定するという二段階方式を採用する。なお使用言語は当面日本語と英語の2カ国語 を想定しており、これによって従来よりも広範囲の知的交流を図っていきたいと考えている。 『中東レビュー』はアジア経済研究所内外にあって中東地域に関心を寄せる方々の、知的・ 情報的な交流のフォーラムとなることを目指している。この小さな試みが中東地域の現状につ いてのバランスの取れた理解とアジ研における中東研究の新たな深化・発展に繋がりますよう、 改めて皆様の温かいご理解とご支援をお願いいたします。 『中東レビュー』編集ボード 委員長 鈴木 均 1 目 次 ウェブ雑誌『中東レビュー』の創刊にあたって 鈴木 均 Hitoshi Suzuki・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・1 ページ 中東政治経済レポート 中東政治の変容とイスラーム主義の限界 Paradigm Shift of the Middle -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL NOTICE GIVEN NO EARLIER THAN 7:00 PM EDT ON SATURDAY 9 JULY 2016 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CATHLEEN COLVIN, individually and as Civil No. __________________ parent and next friend of minors C.A.C. and L.A.C., heirs-at-law and beneficiaries Complaint For of the estate of MARIE COLVIN, and Extrajudicial Killing, JUSTINE ARAYA-COLVIN, heir-at-law and 28 U.S.C. § 1605A beneficiary of the estate of MARIE COLVIN, c/o Center for Justice & Accountability, One Hallidie Plaza, Suite 406, San Francisco, CA 94102 Plaintiffs, v. SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC, c/o Foreign Minister Walid al-Mualem Ministry of Foreign Affairs Kafar Soussa, Damascus, Syria Defendant. COMPLAINT Plaintiffs Cathleen Colvin and Justine Araya-Colvin allege as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. On February 22, 2012, Marie Colvin, an American reporter hailed by many of her peers as the greatest war correspondent of her generation, was assassinated by Syrian government agents as she reported on the suffering of civilians in Homs, Syria—a city beseiged by Syrian military forces. Acting in concert and with premeditation, Syrian officials deliberately killed Marie Colvin by launching a targeted rocket attack against a makeshift broadcast studio in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs where Colvin and other civilian journalists were residing and reporting on the siege. 2. The rocket attack was the object of a conspiracy formed by senior members of the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (the “Assad regime”) to surveil, target, and ultimately kill civilian journalists in order to silence local and international media as part of its effort to crush political opposition. -

People's Power

#2 May 2011 Special Issue PersPectives Political analysis and commentary from the Middle East PeoPle’s Power the arab world in revolt Published by the Heinrich Böll stiftung 2011 This work is licensed under the conditions of a Creative Commons license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. You can download an electronic version online. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: Attribution - you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work); Noncommercial - you may not use this work for commercial purposes; No Derivative Works - you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. editor-in-chief: Layla Al-Zubaidi editors: Doreen Khoury, Anbara Abu-Ayyash, Joachim Paul Layout: Catherine Coetzer, c2designs, Cédric Hofstetter translators: Mona Abu-Rayyan, Joumana Seikaly, Word Gym Ltd. cover photograph: Gwenael Piaser Printed by: www.coloursps.com Additional editing, print edition: Sonya Knox Opinions expressed in articles are those of their authors, and not HBS. heinrich böll Foundation – Middle east The Heinrich Böll Foundation, associated with the German Green Party, is a legally autonomous and intellectually open political foundation. Our foremost task is civic education in Germany and abroad with the aim of promoting informed democratic opinion, socio-political commitment and mutual understanding. In addition, the Heinrich Böll Foundation supports artistic, cultural and scholarly projects, as well as cooperation in the development field. The political values of ecology, democracy, gender democracy, solidarity and non-violence are our chief points of reference. -

PRISM Syrian Supplemental

PRISM syria A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS About PRISM PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners Vol. 4, Syria Supplement on complex and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; 2014 relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education to transform America’s security and development Editor Michael Miklaucic Communications Contributing Editors Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Alexa Courtney communications to: David Kilcullen Nate Rosenblatt Editor, PRISM 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Copy Editors Fort Lesley J. McNair Dale Erikson Washington, DC 20319 Rebecca Harper Sara Thannhauser Lesley Warner Telephone: Nathan White (202) 685-3442 FAX: (202) 685-3581 Editorial Assistant Email: [email protected] Ava Cacciolfi Production Supervisor Carib Mendez Contributions PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers Advisory Board and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians from the United States Dr. Gordon Adams and abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the address above or by email to prism@ Dr. Pauline H. Baker ndu.edu with “Attention Submissions Editor” in the subject line. Ambassador Rick Barton Professor Alain Bauer This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted Ambassador James F. Dobbins without permission of the copyright proprietors. PRISM should be acknowledged whenever material is quoted from or based on its content. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Traditionally a Leader Is One “Who Commands Power and Guides Others

Accountable Leadership. Women’s Empowerment. Youth Development. ANNUAL REPORT 2013 TRADITIONALLY A LEADER IS ONE “WHO COMMANDS POWER AND GUIDES OTHERS. OVER THE YEARS, TIME HAS CHANGED THIS DEFINITION TRANSFORMING THE TRADITIONAL ROLE OF THE LEADER. LEADERSHIP IS NO LONGER JUST A POSITION, IT IS A MINDSET. WHEN LEADERS SEE A NEED FOR CHANGE THEY HAVE TO BE ABLE TO TAKE ACTION. LEADERS HAVE TO TURN THEIR TALENT, KNOWLEDGE AND IDEAS INTO CONSTRUCTIVE STRATEGIES TO ADDRESS SOCIAL POLITICAL AND HUMANITARIAN ISSUES OF ALL KINDS. ” H.E. Mr Nassir Abdulaziz Al-Nasser High Representative for the UN Alliance of Civilizations 2 Accountable Leadership. Women’s Empowerment. Youth Development. Under the auspices of the Municipality of Athens LEADERSHIP & COLLABORATION ATHENS, GREECE - DECEMBER 3 & 4 2013 In association with GLOBAL THINKERS FORUM WAS BORN WITH A VISION AND A MISSION: TO FOSTER POSITIVE “CHANGE AND HELP OUR WORLD BECOME A BETTER PLACE BY NURTURING THE NEW GEN- ” ERATION OF LEADERS. THE SPACE THAT GTF HAS SO SUCCESSFULLY CREATED AS A TRULY PROLIFIC AND DIVERSE FORUM… IS A PLACE WHERE LEADERS CAN COME TOGETHER, SHARE THEIR STORIES AND ACHIEVEMENTS, COLLABO- RATE, AND POINT TOWARDS THE FUTURE. IT IS A PLACE WHERE WE GENERATE NEW KNOWL- EDGE AND WE PASS THIS NEW KNOWLEDGE TO THE YOUNGER GENERATIONS. Elizabeth Filippouli Founder & CEO Global Thinkers Forum ” 3 GLOBAL THINKERS FORUM 2013 ‘LEADERSHIP & COLLABORATION’ A very timely conversation around leadership in a changing world took place in Athens, Greece in the beginning of December. Global Thinkers Forum organized its annual event and the GTF 2013 Awards for Excellence under the theme ‘Leadership & Collaboration’ convening over 30 leaders and thought leaders from 18 countries to discuss leadership, ethics, collaboration & cross-cultural understanding. -

The Alawite Dilemma in Homs Survival, Solidarity and the Making of a Community

STUDY The Alawite Dilemma in Homs Survival, Solidarity and the Making of a Community AZIZ NAKKASH March 2013 n There are many ways of understanding Alawite identity in Syria. Geography and regionalism are critical to an individual’s experience of being Alawite. n The notion of an »Alawite community« identified as such by its own members has increased with the crisis which started in March 2011, and the growth of this self- identification has been the result of or in reaction to the conflict. n Using its security apparatus, the regime has implicated the Alawites of Homs in the conflict through aggressive militarization of the community. n The Alawite community from the Homs area does not perceive itself as being well- connected to the regime, but rather fears for its survival. AZIZ NAKKASH | THE ALAWITE DILEMMA IN HOMS Contents 1. Introduction ...........................................................1 2. Army, Paramilitary Forces, and the Alawite Community in Homs ...............3 2.1 Ambitions and Economic Motivations ......................................3 2.2 Vulnerability and Defending the Regime for the Sake of Survival ..................3 2.3 The Alawite Dilemma ..................................................6 2.4 Regime Militias .......................................................8 2.5 From Popular Committees to Paramilitaries ..................................9 2.6 Shabiha Organization ..................................................9 2.7 Shabiha Talk ........................................................10 2.8 The