Denning Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entdeckungsreise

Entdeckungsreise Dieses auch für hiesige Verhältnisse eher kleine Dorf – seine Einwoh- nerzahl schwankt um die 200 – liegt als auffallend geschlossene Sied- lung an der Nordflanke des Mittelprättigaus. Diese wird im von Ost nach West orientierten Tal als Schatten- oder ‚Litzisiitä’ bezeichnet, und daher soll auch der Name ‚Conters’ stammen, was in Romanisch, das hier während ca. 1000 Jahren bis ins 15. Jahrhundert gesprochen wurde, ‚gegenüber’ bedeutet. Wir sprechen diesen Dorfnamen immer noch als ‚Guntersch’ aus. Allerdings hat der deutsche Prof. W. Obermüller, ein fundierter Kenner der keltischen Sprache, schon vor mehr als 100 Jahren auf diesen Dorf- namen hingewiesen und ihn in seinem Werk ‚Deutsch-keltisches Wör- terbuch’ (Band I S.572) wesentlich anders gedeutet: „Guntershausen am Zusammenfluss der Fulda und Edder in Niederhessen kann als Berg- hausen erklärt werden, wie Cunters, ein Dorfname in Rhätien, der aus cuanna Berg und tuaras Häuser zusammengesetzt ist. Gunter ist in- dess ein Mannsname, – alt Gundihar, Gundikar, – der Waldmann bedeu- tet, von grund, gwydd, coed Wald und air Mann. ...“ Falls dies zutrifft und unser Dorfname ‚Conters’ keltischen Ursprungs ist, kann davon ausgegangen werden, dieser Siedlungsplatz sei nicht erst vor etwa 1500, sondern schon 1000 Jahre früher als solcher herangezogen wor- den. Wer in Graubünden historisch etwas umfassender interessiert ist, als nur hinsichtlich des Geschehens während der Kämpfe um Macht und Ehre, kommt um den Namen des Bündner Pfarrers Nicolin Sererhard (1689-1755) nicht herum: Er ist in Küblis geboren und aufgewachsen. Später schrieb er, als Seewiser Pfarrer, ein Buch mit dem Titel: „Einfalte Delineation (einfache Beschreibung) aller Gemeinden gemeiner dreyen Bünden“, das 1742 herauskam. -

2020 Jahresberichte Rechnungsabschlüsse

2020 Jahresberichte Rechnungsabschlüsse Region Prättigau/Davos Jahresbericht 2020 Die Covid-19-Pandemie war im Jahr 2020 schäfte und Themen wurden einstimmig ge- auch bei der Region Prättigau/Davos das do- nehmigt oder zur weiteren Bearbeitung frei ge- minierende Thema. In vielen Bereichen sind geben. schliesslich physische Kontakte das A und O des Betriebs, sei das nun bei Zivilstandsamt, Die zweite Präsidentenkonferenz des Jahres Berufsbeistandschaft oder Betreibungs- und fand am 26. November im Theorieraum des Konkursamt, bei der Regionalentwicklung oder Feuerwehrlokals in Klosters statt. Die Ver- auch bei der Musikschule Prättigau. Normale sammlung stand im Zeichen des Doppelwech- Besprechungen wurden im Frühling zunächst sels an der Spitze der Region auf Anfang reihenweise abgesagt und fanden dann nur 2021. Da Kurt Steck (Klosters-Serneus) sowie noch unter erschwerten Umständen oder als Tarzisius Caviezel (Davos) ihre Ämter als Ge- Videokonferenz statt. Auch die Präsidenten- meindepräsidenten den Nachfolgern überga- konferenz, für die der Ratsstuben-Tisch im ben, mussten sie auch ihre Aufgaben als Prä- Klosterser Rathaus normalerweise gerade sident und Vizepräsident der Region abgeben. gross genug ist, fand sich im Juni in einem Beide hatten den erfolgreichen Aufbau der weitläufigen Saal mit Einzeltischen und Ver- neuen Region ab 2015 eng begleitet und den stärkeranlage im Davoser Kongresshaus wie- fünfköpfigen Regionalausschuss geführt. Als der. Wo möglich waren die Mitarbeitenden zu- Präsident der Region war Kurt Steck zudem für dem im Homeoffice, was dank der (zufällig) er- die Vertretung gegen aussen und für das Per- neuerten IT-Infrastruktur im März 2020 auch sonal verantwortlich. sehr gut klappte. Deutlich wurde jedoch über- all, wie wichtig der informelle Austausch wäh- Als neuen Vorsitzenden wählten die Präsiden- rend der Arbeit, an Sitzungen selbst, danach tinnen und Präsidenten den Jenazer Werner bei einer Kaffeerunde in der Beiz oder beim Bär. -

Understanding the New Market: NSAA's Millennial Study

Understanding the New Market: NSAA’s Millennial Study 2015 ISKINY – PSAA Expo Lake Placid Conference Center September 22nd, 2015 Before we begin, some ground rules. Don’t Confuse Societal Trends with Generational Trends Don’t Life Stage Differences for with Generational Differences And remember, this is more about us than them What’s all the fuss? The Birth of the Teenager in the 20th Century The 21st Century Brings the Concept of the “Emerging Adult” Five Milestones: • Completing School • Leaving Home • Becoming Financially Independent • Marrying • Having a Child In the recent past the majority had hit all of these goals by age 30, today very few have reached these goals by age 30, nor would some find it desirable to do so. Millennials: • Born after 1980. • Currently age 35 and under. • 18-35 year olds are 24.5% of population. Size of Age Range in 2004 vs. 2014 30 2004 Over 9M more people 25.5 25 2014 in this age category 23.0 than in 2004 21.7 20 17.9 17.9 15.9 15 12.4 13.2 10 Population (in (in millions) Population 5 0 18 to 20 21 to 24 25 to 29 30 to 35 Age Range: Size of Cohort Accounted for by Age Group and Percent Non- White, Non-hispanic within Age Group: 2014 50% 50% 44% 44% 45% 43% 42% 45% 40% 40% Percent of Current Cohort 35% Percent Non-White or Hispanic 33% 35% 30% 28% 30% Waiting for 2042 25% 23% 25% 20% 20% 17% Percent Minority Percent Percent of Cohort Percent 15% 15% 10% 10% 5% 5% 0% 0% 18 to 20 21 to 24 25 to 29 30 to 35 Age Group: Percent of Total Population in 2014 9% 8.0% 8% Overall 24.5% of Total U.S. -

"Forest Use and Regulation Around a Swiss Alpine Community (Davos, Graubuenden)"

1 "FOREST USE AND REGULATION AROUND A SWISS ALPINE COMMUNITY (DAVOS, GRAUBUENDEN)" MARTIN F. PRICE NATIONAL CENTER FOR ATMOSPHERIC RESEARCH P.O. BOX 3000, BOULDER, CO 80307 PAPER FOR PRESENTATION AT 1990 ANNUAL MEETING INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF COMMON PROPERTY DUKE UNIVERSITY, 29 SEPTEMBER 1990 REVISED 25 SEPTEMBER 1990 This paper is based on research supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the Swiss Man and the Biosphere program. The National Center for Atmospheric Research is supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation. 2 Forests were vital in the traditional economy of the Alps, providing wood for fuel and other domestic purposes, agriculture, and construction. The sale of wood also provided an important source of income in many communes into the mid- 20th century, Forest use has been regulated in the Swiss Alps by some Communes for at least seven centuries. Cantonal regulation in most mountain cantons began in the first half of the 19th century, and federal regulation began with the passage of the Forest Police Law in 1876. This law, revised in 1902, remains the basis for the management of the forests of the Swiss Alps. This paper traces the use and regulation of the forests of Davos, in the Canton of Graubünden (Grisons), in eastern Switzerland, concentrating particularly on the 19th and 20th centuries. Like the majority of the communities of the Swiss Alps, Davos has a service economy with vestiges of agriculture. However, tourism in Davos both has a longer history, and has developed to a greater extent, than in most communities. -

Consistency of Total Column Ozone Measurements Between the Brewer

Consistency of total column ozone measurements between the Brewer and Dobson spectroradiometers of the LKO Arosa and PMOD/WRC Davos Julian Gröbner1, Herbert Schill1, Luca Egli1, and René Stübi2 1 Physikalisch-Meteorologisches Observatorium Davos, World Radiation Center, PMOD/WRC, Davos, Switzerland 2 MeteoSwiss, Payerne, Switzerland Introduction The world's longest continuous total column ozone time series was initiated in 1926 at the Lichtklimatisches Observatorium (LKO), at Arosa, in the Swiss Alps with Dobson D002 (Staehelin, et al., 2018). Currently, three Dobson (D051, D062, D101) and three Brewer (B040, B072, B156) spectroradiometers are operated continuously. Since 2010, the spectroradiometers have been successively relocated to the PMOD/WRC, located in the nearby valley of Davos (1590~m.a.s.l.), at 12 km horizontal distance from Arosa (1850~m.a.s.l.). The last two instruments, Brewer B040 and Dobson D062 have been transferred in February 2021, successfully completing the transfer of the measurements from LKO Arosa to PMOD/WRC, Davos. Figure 3. View inside the MeteoSwiss with the Figure 1. Yearly (red), 11-year (burgundy and Gaussian-filtered Figure 2. The MeteoSwiss Brewer and Dobson automated Dobson spectroradiometer triad. 11-year (light green) averages of homogenized total column spectroradiometers in operation at PMOD/WRC. ozone at Arosa. Below are the timelines for the different instruments in operation at LKO Arosa and PMOD/WRC Davos. The problem The total column ozone measurements between Dobson and Brewer spectroradiometers show a significant seasonal variation of 1.6%, which is correlated to the effective ozone temperature. The effective ozone temperature is on average 225.2 K at PMOD/WRC, with a seasonal variation of amplitude 5.7 K. -

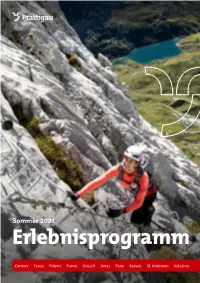

Erlebnisprogramm

Sommer 2021 Erlebnisprogramm Conters Fanas Fideris Furna Grüsch Jenaz Pany Seewis St. Antönien Valzeina Gästekarte Prättigau Ihre Zugangskarte für attraktive und erlebnisreiche Angebote im Prättigau Gästekarte Vorname / Name Christa Tünscher 2 Erwachsene 2 Bis 6 Jahre 1 Ab 6 Jahre Gültig vom 01.08.2021 bis 08.08.2021 Erhältlich bei Ihrem Gastgeber oder bei den Gäste-Informations stellen (siehe Seite 19) Nutzen Sie die Gelegenheit und probieren Sie etwas Neues aus! Das aktuelle Erlebnisprogramm finden Sie auf praettigau.info/gaestekarte Programmänderungen vorbehalten. Prättigau Tourismus Valzeinastrasse 6, 7214 Grüsch Tel. +41 81 325 11 11 praettigau.info [email protected] facebook.com/praettigau instagram.com/praettigau.ch youtube.com/praettigau 2 Willkommen im Prättigau Liebe Gäste In dieser Broschüre finden Sie zahlreiche Bitte beachten Sie die Anmeldefristen unvergessliche Aktivitäten und Ange- für einzelne Angebote und weisen Sie bote. Lassen Sie sich inspirieren und bei der Anmeldung auf Ihre Gäste- profitieren Sie von attraktiven Kondi- karte hin. Die Kosten sind in Schweizer tionen mit der Gästekarte Prättigau. So Franken ausgewiesen und bar vor Ort zu wird sich Ihr Ferien-Tagebuch schnell mit bezahlen. Die Versicherung ist Sache der spannenden Erlebnissen und bleibenden Teil nehmenden. Erinnerungen füllen. Wir wünschen Ihnen viel Vergnügen Wir unterstützen Sie gerne bei der Ge- auf Ihrer persönlichen Entdeckungstour staltung eines abwechslungs reichen durch das Prättigau! Aufenthalts mit Ihrer Gästekarte. 3 Wasser Schwimmbad Pany Gültig 29. Mai – 29. August 2021 Die gepflegte und gut eingerichtete Anlage mit 33 m-Becken, Nichtschwimmerbecken Öffnungszeiten und Kinderplanschbecken liegt an herrlicher (bei guter Witterung) Panorama lage oberhalb von Pany. Mo – Fr 10 – 19 Uhr Grosszügige Liegewiese, Grillstelle, verschiedene Sa – So 9 – 19 Uhr Spiele und vieles mehr. -

HIV Twenty-Eight Years Later: What Is the Truth? Gary Null, Phd December 3, 2012

HIV Twenty-Eight Years Later: What is the Truth? Gary Null, PhD December 3, 2012 In the May 4, 1984 issue of the prestigious journal Science, one of the most important research papers of the last quarter century was published. “Frequent Detection and Isolation of Cytopathic Retroviruses (HTLV-III) from Patients with AIDS and at Risk for AIDS” would rapidly become the medical Magna Carta for the entire gold rush to develop diagnostic methods to identify the presence of HIV in human blood and to invent pharmaceutical drugs and vaccines in a global war against AIDS. This paper, along with three others published in the same issue of Science, was written by Dr. Robert Gallo, then head of the Laboratory of Tumor Cell Biology (LTCB) at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in Bethesda, Maryland, and his lead researcher Dr. Mikulas Popovic. To this day, this article continues to document the most cited research to prove the HIV hypothesis in scientific papers and places like the nation’s Centers of Disease Control (CDC) website. For virologists, molecular biologists and other infectious disease researchers, particularly those tied to the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries and the national medical and health institutions, the news of Gallo’s discovery was manna rained down from heaven. All research into other possible causes for the AIDS crisis ended abruptly. As soon as the winds shifted away from earlier efforts to find the cause of AIDS —people’s lifestyles, immune suppressing illicit drug use and other health risks and illnesses that adversely affect the body’s immune system — to that of a single new virus, the case was closed. -

Bar Food – Outro (Dessert) Soft Drinks Juice Coffee, T

BAR FOOD – PRE CHORUS (VORSPEISEN) SHOOTERS SOFT DRINKS Justin’s Caesar ‹‹Timber›› Salad 24 Born To Kill 8 Coca Cola / Coca Cola Zero 33 cl 5 Lattichsalat, Pouletbrust, Speckstreifen, Baileys, Kahlua, Stroh Rum Sinalco 33 cl 5 Caesar Dressing, gehobelter Parmesan, Croutons baby lettuce, stir-fried chicken, bacon, Stairway To Heaven 8 Elmer Citro 33 cl 5 Caesar dressing, Parmesan shavings, croutons Sambuca, Galliano, Coffe Beans Rivella Rot / Blau 33 cl 5 Jack W’s Tortillas 16 Goodbye Kiss 8 Stolinchnaya Ginger Beer 25 cl 5 Tortilla Chips, hausgemachte Guacamole Amaretto, Stolichnaya Vodka, Lime Cordial, Stroh Rum Club-Mate 33 cl 7 tortilla chips, homemade guacamole I Shot The Sheriff 8 Swiss Mountain Spring 20 cl 7 Midori Melon Liqueur, Green Chartreuse, Fresh Mint Tonic / GinGer Ale / Bitter Lemon Santana’s Rock Nachos 18 Nachos, Käse, Tomaten, Zwiebel, Jalapeno, Sauerrahm Dip Vanilla Ice 8 Red Bull 25 cl 7 nachos, cheese, tomatoes, onions, jalapeno, sour cream dip Galliano Vanilla Liqueur, Espresso, Fresh Cream San Bitter 10 cl 5 Homemade Ice Tea / Limo 50 cl 6 Water still / Sparkling a discreation 70 cl 3 BAR FOOD – LYRICS (HAUPTSPEISEN) WARM UP YOUR LIP (HOT DRINKS) Tupelo Chicken 21 Get Lucky 14 Panierte Schweizer Pouletbruststreifen, Sailor Jerry Spiced Rum, Passoa Liqueur, JUICE Steak Fries, Dijon senf-Honig Dip Passion Fruit Syrup, Lime Juice, Ginger Beer breaded chicken breast fingers, steak fries, Apple juice 25 cl 5 Dijon mustard and honey dip Smoke On The Water 14 orange juice 25 cl 5 Tatra Tea Liqueur, Stroh Rum, Ginger Monin, -

Olympic Charter 1956

THE OLYMPIC GAMES CITIUS - ALTIUS - FORTIUS 1956 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE CAMPAGNE MON REPOS LAUSANNE (SWITZERLAND) THE OLYMPIC GAMES FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES RULES AND REGULATIONS GENERAL INFORMATION CITIUS - ALTIUS - FORTIUS PIERRE DE GOUBERTIN WHO REVIVED THE OLYMPIC GAMES President International Olympic Committee 1896-1925. THE IMPORTANT THING IN THE OLYMPIC GAMES IS NOT TO WIN BUT TO TAKE PART, AS THE IMPORTANT THING IN LIFE IS NOT THE TRIUMPH BUT THE STRUGGLE. THE ESSENTIAL THING IS NOT TO HAVE CONQUERED BUT TO HAVE FOUGHT WELL. INDEX Nrs Page I. 1-8 FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES 9 II. HULES AND REGULATIONS OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE 9 Objects and Powers II 10 Membership 11 12 President and Vice-Presidents 12 13 The Executive Board 12 17 Chancellor and Secretary 14 18 Meetings 14 20 Postal Vote 15 21 Subscription and contributions 15 22 Headquarters 15 23 Supreme Authority 15 III. 24-25 NATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEES 16 IV. GENERAL RULES OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES 26 Definition of an Amateur 19 27 Necessary conditions for wearing the colours of a country 19 28 Age limit 19 29 Participation of women 20 30 Program 20 31 Fine Arts 21 32 Demonstrations 21 33 Olympic Winter Games 21 34 Entries 21 35 Number of entries 22 36 Number of Officials 23 37 Technical Delegates 23 38 Officials and Jury 24 39 Final Court of Appeal 24 40 Penalties in case of Fraud 24 41 Prizes 24 42 Roll of Honour 25 43 Explanatory Brochures 25 44 International Sport Federations 25 45 Travelling Expenses 26 46 Housing 26 47 Attaches 26 48 Reserved Seats 27 49 Photographs and Films 28 50 Alteration of Rules and Official text 28 V. -

Media Info 40J WC

FÉDÉRATION INTERNATIONALE DE SKI INTERNATIONAL SKI FEDERATION INTERNATIONALER SKI VERBAND CH-3653 Oberhofen (Switzerland), Tel. +41 (33) 244 61 61, Fax +41 (33) 244 61 71 FIS-Website: http://www.fis-ski.com FIS MEDIA INFO 40 th season of Alpine FIS World Cup – a kaleidoscope of skiing This winter the Alpine Ski World Cup, cooked up by a few skiing pioneers in the Chilean Andes, celebrates its 40 year anniversary. The four decades have been characterized by triumphs and tragedies, beaming winners and dazzling stars. The World Cup, created by some progressive ski freaks, changed the world of skiing. The journalist Serge Lang, who worked for the French newspaper “L’Equipe”, Honoré Bonnet and Bob Beattie, team coaches of the French and American teams, and later Austria’s “Sportwart” Sepp Sulzberger conspired during the long nights of the summer World Championships at Portillo in 1966. At that time “L’Equipe” had invited the best skiers to a “challenge”, a competition analogous to bicycling, but taken notice of by hardly anybody (except Serge Lang), and the trophy to be won, a ski set with brilliants, was not even appreciated by the winners Marielle Goitschel and Karl Schranz. While on Portilllo’s altitude of 3000 m the athletes were killing time by throwing cakes and ash trays, the Gang of Four (as Serge Lang called his creative team), of which only Bob Beattie is still alive, were hatching their project day and night. When the draft was more or less finished, they presented it to FIS president Marc Hodler. Unexpectedly and undiplomatically the ski boss reacted fast and announced to the press on August 11, 1966: “Gentlemen, we have a World Cup”. -

The Role of Skis and Skiing in the Settlement of Early Scandinavia

The Role of Skis and Skiing in the Settlement of Early Scandinavia JOHN WEINSTOCK The Northern Review #25/26 (Summer 2005): 172-196. Introduction Skiing as a modern sport spread from Norway in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to other countries where there was snow during some portion of the year. Many people had read Fridtjof Nansen’s account of his 1888-89 trek on skis over the inland ice of Greenland in his book Paa ski over Grønland, which appeared in Norwegian and other languages in 1890.1 The book helped make skiing a household word. Not so well known is the role of the Sámi (formerly Lapps) in the evolution of skiing. This arti- cle aims to sketch the ear ly history of skiing from its birth in the Stone Age to a period only some centuries ago. I suggest that Finno-Ugrian cultural complexes moved into Fennoscandia (the Scandinavian peninsula) from the east and south in the late Stone Age, bringing skis with them as one as- pect of their material culture. Germanic groups migrated northward into Scandinavia much later on. They too may have brought skis with them, but their skis were not nearly as technologically advanced as the Sámi skis. When Germanic groups came in contact with the Sámi, they profi ted from the latter group’s mastery of skis and skiing.2 Origins of Skiing The roots of skiing go back much further than a century or two. Written sources as early as 211 BC mention skis and skiing. There are rock carv- ings in northwest Russia and northern Norway depicting skiers that are upwards of four thousand years old. -

The Cradle of Alpine Skiing - Milestones in the History of Skiing on the Arlberg

PRESS RELEASE The cradle of Alpine skiing - Milestones in the history of skiing on the Arlberg Lech Zürs am Arlberg, 29. October 2020. The cradle of Alpine skiing is located in the heart of a vast mountainous area between Tyrol and Vorarlberg. This region of Austria, one of the snowiest in the Alps, inspired daring young ski pioneers at the beginning of the 20th century. Their inventiveness and ingenuity both shaped and influenced the sport of alpine skiing. With 88 lifts and cable cars, 305 km of ski runs and 200 km of high-Alpine powder snow runs, Lech Zürs is today part of the largest and most extensive ski area in Austria. Moreover, "Ski Arlberg" is one of the world’s 5 largest ski regions. What separates this area from others is the unrivalled passion for skiing, which has shaped the development of Lech Zürs for more than 100 years. More than any other winter sports destination, the Arlberg defines ski culture and ingenuity. Where history is made... The Arlberg's legendary status is rooted in its storied history, geography, and extensive cable car infrastructure. No one better embodies this local pioneering spirit better than Hannes Schneider. Born in Stuben am Arlberg, he founded Austria's first ski school in St. Anton in 1921, thereby revolutionising skiing with his ‘stem christie’ technique. The first surface lift in Austria was built in Zürs in 1937 to suit the growing number of young amateur sports enthusiasts. In the same year, the Galzigbahn became the first cable car on the Arlberg designed specifically for winter tourism.