"Forest Use and Regulation Around a Swiss Alpine Community (Davos, Graubuenden)"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entdeckungsreise

Entdeckungsreise Dieses auch für hiesige Verhältnisse eher kleine Dorf – seine Einwoh- nerzahl schwankt um die 200 – liegt als auffallend geschlossene Sied- lung an der Nordflanke des Mittelprättigaus. Diese wird im von Ost nach West orientierten Tal als Schatten- oder ‚Litzisiitä’ bezeichnet, und daher soll auch der Name ‚Conters’ stammen, was in Romanisch, das hier während ca. 1000 Jahren bis ins 15. Jahrhundert gesprochen wurde, ‚gegenüber’ bedeutet. Wir sprechen diesen Dorfnamen immer noch als ‚Guntersch’ aus. Allerdings hat der deutsche Prof. W. Obermüller, ein fundierter Kenner der keltischen Sprache, schon vor mehr als 100 Jahren auf diesen Dorf- namen hingewiesen und ihn in seinem Werk ‚Deutsch-keltisches Wör- terbuch’ (Band I S.572) wesentlich anders gedeutet: „Guntershausen am Zusammenfluss der Fulda und Edder in Niederhessen kann als Berg- hausen erklärt werden, wie Cunters, ein Dorfname in Rhätien, der aus cuanna Berg und tuaras Häuser zusammengesetzt ist. Gunter ist in- dess ein Mannsname, – alt Gundihar, Gundikar, – der Waldmann bedeu- tet, von grund, gwydd, coed Wald und air Mann. ...“ Falls dies zutrifft und unser Dorfname ‚Conters’ keltischen Ursprungs ist, kann davon ausgegangen werden, dieser Siedlungsplatz sei nicht erst vor etwa 1500, sondern schon 1000 Jahre früher als solcher herangezogen wor- den. Wer in Graubünden historisch etwas umfassender interessiert ist, als nur hinsichtlich des Geschehens während der Kämpfe um Macht und Ehre, kommt um den Namen des Bündner Pfarrers Nicolin Sererhard (1689-1755) nicht herum: Er ist in Küblis geboren und aufgewachsen. Später schrieb er, als Seewiser Pfarrer, ein Buch mit dem Titel: „Einfalte Delineation (einfache Beschreibung) aller Gemeinden gemeiner dreyen Bünden“, das 1742 herauskam. -

2020 Jahresberichte Rechnungsabschlüsse

2020 Jahresberichte Rechnungsabschlüsse Region Prättigau/Davos Jahresbericht 2020 Die Covid-19-Pandemie war im Jahr 2020 schäfte und Themen wurden einstimmig ge- auch bei der Region Prättigau/Davos das do- nehmigt oder zur weiteren Bearbeitung frei ge- minierende Thema. In vielen Bereichen sind geben. schliesslich physische Kontakte das A und O des Betriebs, sei das nun bei Zivilstandsamt, Die zweite Präsidentenkonferenz des Jahres Berufsbeistandschaft oder Betreibungs- und fand am 26. November im Theorieraum des Konkursamt, bei der Regionalentwicklung oder Feuerwehrlokals in Klosters statt. Die Ver- auch bei der Musikschule Prättigau. Normale sammlung stand im Zeichen des Doppelwech- Besprechungen wurden im Frühling zunächst sels an der Spitze der Region auf Anfang reihenweise abgesagt und fanden dann nur 2021. Da Kurt Steck (Klosters-Serneus) sowie noch unter erschwerten Umständen oder als Tarzisius Caviezel (Davos) ihre Ämter als Ge- Videokonferenz statt. Auch die Präsidenten- meindepräsidenten den Nachfolgern überga- konferenz, für die der Ratsstuben-Tisch im ben, mussten sie auch ihre Aufgaben als Prä- Klosterser Rathaus normalerweise gerade sident und Vizepräsident der Region abgeben. gross genug ist, fand sich im Juni in einem Beide hatten den erfolgreichen Aufbau der weitläufigen Saal mit Einzeltischen und Ver- neuen Region ab 2015 eng begleitet und den stärkeranlage im Davoser Kongresshaus wie- fünfköpfigen Regionalausschuss geführt. Als der. Wo möglich waren die Mitarbeitenden zu- Präsident der Region war Kurt Steck zudem für dem im Homeoffice, was dank der (zufällig) er- die Vertretung gegen aussen und für das Per- neuerten IT-Infrastruktur im März 2020 auch sonal verantwortlich. sehr gut klappte. Deutlich wurde jedoch über- all, wie wichtig der informelle Austausch wäh- Als neuen Vorsitzenden wählten die Präsiden- rend der Arbeit, an Sitzungen selbst, danach tinnen und Präsidenten den Jenazer Werner bei einer Kaffeerunde in der Beiz oder beim Bär. -

Consistency of Total Column Ozone Measurements Between the Brewer

Consistency of total column ozone measurements between the Brewer and Dobson spectroradiometers of the LKO Arosa and PMOD/WRC Davos Julian Gröbner1, Herbert Schill1, Luca Egli1, and René Stübi2 1 Physikalisch-Meteorologisches Observatorium Davos, World Radiation Center, PMOD/WRC, Davos, Switzerland 2 MeteoSwiss, Payerne, Switzerland Introduction The world's longest continuous total column ozone time series was initiated in 1926 at the Lichtklimatisches Observatorium (LKO), at Arosa, in the Swiss Alps with Dobson D002 (Staehelin, et al., 2018). Currently, three Dobson (D051, D062, D101) and three Brewer (B040, B072, B156) spectroradiometers are operated continuously. Since 2010, the spectroradiometers have been successively relocated to the PMOD/WRC, located in the nearby valley of Davos (1590~m.a.s.l.), at 12 km horizontal distance from Arosa (1850~m.a.s.l.). The last two instruments, Brewer B040 and Dobson D062 have been transferred in February 2021, successfully completing the transfer of the measurements from LKO Arosa to PMOD/WRC, Davos. Figure 3. View inside the MeteoSwiss with the Figure 1. Yearly (red), 11-year (burgundy and Gaussian-filtered Figure 2. The MeteoSwiss Brewer and Dobson automated Dobson spectroradiometer triad. 11-year (light green) averages of homogenized total column spectroradiometers in operation at PMOD/WRC. ozone at Arosa. Below are the timelines for the different instruments in operation at LKO Arosa and PMOD/WRC Davos. The problem The total column ozone measurements between Dobson and Brewer spectroradiometers show a significant seasonal variation of 1.6%, which is correlated to the effective ozone temperature. The effective ozone temperature is on average 225.2 K at PMOD/WRC, with a seasonal variation of amplitude 5.7 K. -

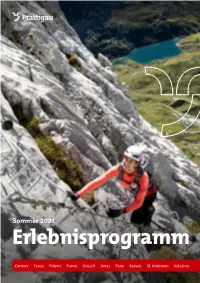

Erlebnisprogramm

Sommer 2021 Erlebnisprogramm Conters Fanas Fideris Furna Grüsch Jenaz Pany Seewis St. Antönien Valzeina Gästekarte Prättigau Ihre Zugangskarte für attraktive und erlebnisreiche Angebote im Prättigau Gästekarte Vorname / Name Christa Tünscher 2 Erwachsene 2 Bis 6 Jahre 1 Ab 6 Jahre Gültig vom 01.08.2021 bis 08.08.2021 Erhältlich bei Ihrem Gastgeber oder bei den Gäste-Informations stellen (siehe Seite 19) Nutzen Sie die Gelegenheit und probieren Sie etwas Neues aus! Das aktuelle Erlebnisprogramm finden Sie auf praettigau.info/gaestekarte Programmänderungen vorbehalten. Prättigau Tourismus Valzeinastrasse 6, 7214 Grüsch Tel. +41 81 325 11 11 praettigau.info [email protected] facebook.com/praettigau instagram.com/praettigau.ch youtube.com/praettigau 2 Willkommen im Prättigau Liebe Gäste In dieser Broschüre finden Sie zahlreiche Bitte beachten Sie die Anmeldefristen unvergessliche Aktivitäten und Ange- für einzelne Angebote und weisen Sie bote. Lassen Sie sich inspirieren und bei der Anmeldung auf Ihre Gäste- profitieren Sie von attraktiven Kondi- karte hin. Die Kosten sind in Schweizer tionen mit der Gästekarte Prättigau. So Franken ausgewiesen und bar vor Ort zu wird sich Ihr Ferien-Tagebuch schnell mit bezahlen. Die Versicherung ist Sache der spannenden Erlebnissen und bleibenden Teil nehmenden. Erinnerungen füllen. Wir wünschen Ihnen viel Vergnügen Wir unterstützen Sie gerne bei der Ge- auf Ihrer persönlichen Entdeckungstour staltung eines abwechslungs reichen durch das Prättigau! Aufenthalts mit Ihrer Gästekarte. 3 Wasser Schwimmbad Pany Gültig 29. Mai – 29. August 2021 Die gepflegte und gut eingerichtete Anlage mit 33 m-Becken, Nichtschwimmerbecken Öffnungszeiten und Kinderplanschbecken liegt an herrlicher (bei guter Witterung) Panorama lage oberhalb von Pany. Mo – Fr 10 – 19 Uhr Grosszügige Liegewiese, Grillstelle, verschiedene Sa – So 9 – 19 Uhr Spiele und vieles mehr. -

Bar Food – Outro (Dessert) Soft Drinks Juice Coffee, T

BAR FOOD – PRE CHORUS (VORSPEISEN) SHOOTERS SOFT DRINKS Justin’s Caesar ‹‹Timber›› Salad 24 Born To Kill 8 Coca Cola / Coca Cola Zero 33 cl 5 Lattichsalat, Pouletbrust, Speckstreifen, Baileys, Kahlua, Stroh Rum Sinalco 33 cl 5 Caesar Dressing, gehobelter Parmesan, Croutons baby lettuce, stir-fried chicken, bacon, Stairway To Heaven 8 Elmer Citro 33 cl 5 Caesar dressing, Parmesan shavings, croutons Sambuca, Galliano, Coffe Beans Rivella Rot / Blau 33 cl 5 Jack W’s Tortillas 16 Goodbye Kiss 8 Stolinchnaya Ginger Beer 25 cl 5 Tortilla Chips, hausgemachte Guacamole Amaretto, Stolichnaya Vodka, Lime Cordial, Stroh Rum Club-Mate 33 cl 7 tortilla chips, homemade guacamole I Shot The Sheriff 8 Swiss Mountain Spring 20 cl 7 Midori Melon Liqueur, Green Chartreuse, Fresh Mint Tonic / GinGer Ale / Bitter Lemon Santana’s Rock Nachos 18 Nachos, Käse, Tomaten, Zwiebel, Jalapeno, Sauerrahm Dip Vanilla Ice 8 Red Bull 25 cl 7 nachos, cheese, tomatoes, onions, jalapeno, sour cream dip Galliano Vanilla Liqueur, Espresso, Fresh Cream San Bitter 10 cl 5 Homemade Ice Tea / Limo 50 cl 6 Water still / Sparkling a discreation 70 cl 3 BAR FOOD – LYRICS (HAUPTSPEISEN) WARM UP YOUR LIP (HOT DRINKS) Tupelo Chicken 21 Get Lucky 14 Panierte Schweizer Pouletbruststreifen, Sailor Jerry Spiced Rum, Passoa Liqueur, JUICE Steak Fries, Dijon senf-Honig Dip Passion Fruit Syrup, Lime Juice, Ginger Beer breaded chicken breast fingers, steak fries, Apple juice 25 cl 5 Dijon mustard and honey dip Smoke On The Water 14 orange juice 25 cl 5 Tatra Tea Liqueur, Stroh Rum, Ginger Monin, -

Olympic Charter 1956

THE OLYMPIC GAMES CITIUS - ALTIUS - FORTIUS 1956 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE CAMPAGNE MON REPOS LAUSANNE (SWITZERLAND) THE OLYMPIC GAMES FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES RULES AND REGULATIONS GENERAL INFORMATION CITIUS - ALTIUS - FORTIUS PIERRE DE GOUBERTIN WHO REVIVED THE OLYMPIC GAMES President International Olympic Committee 1896-1925. THE IMPORTANT THING IN THE OLYMPIC GAMES IS NOT TO WIN BUT TO TAKE PART, AS THE IMPORTANT THING IN LIFE IS NOT THE TRIUMPH BUT THE STRUGGLE. THE ESSENTIAL THING IS NOT TO HAVE CONQUERED BUT TO HAVE FOUGHT WELL. INDEX Nrs Page I. 1-8 FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES 9 II. HULES AND REGULATIONS OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE 9 Objects and Powers II 10 Membership 11 12 President and Vice-Presidents 12 13 The Executive Board 12 17 Chancellor and Secretary 14 18 Meetings 14 20 Postal Vote 15 21 Subscription and contributions 15 22 Headquarters 15 23 Supreme Authority 15 III. 24-25 NATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEES 16 IV. GENERAL RULES OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES 26 Definition of an Amateur 19 27 Necessary conditions for wearing the colours of a country 19 28 Age limit 19 29 Participation of women 20 30 Program 20 31 Fine Arts 21 32 Demonstrations 21 33 Olympic Winter Games 21 34 Entries 21 35 Number of entries 22 36 Number of Officials 23 37 Technical Delegates 23 38 Officials and Jury 24 39 Final Court of Appeal 24 40 Penalties in case of Fraud 24 41 Prizes 24 42 Roll of Honour 25 43 Explanatory Brochures 25 44 International Sport Federations 25 45 Travelling Expenses 26 46 Housing 26 47 Attaches 26 48 Reserved Seats 27 49 Photographs and Films 28 50 Alteration of Rules and Official text 28 V. -

Stratospheric Ozone Measurements at Arosa (Switzerland): History and Scientific Relevance

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 6567–6584, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-6567-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Stratospheric ozone measurements at Arosa (Switzerland): history and scientific relevance Johannes Staehelin1, Pierre Viatte2, Rene Stübi2, Fiona Tummon1, and Thomas Peter1 1Institute for Atmospheric and Climate Science, ETHZ, Zürich, Switzerland 2Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss, Payerne, Switzerland Correspondence: Johannes Staehelin ([email protected]) Received: 20 November 2017 – Discussion started: 29 November 2017 Revised: 15 March 2018 – Accepted: 22 March 2018 – Published: 8 May 2018 Abstract. In 1926 stratospheric ozone measurements began identifying potentially unexpected stratospheric responses to at the Light Climatic Observatory (LKO) in Arosa (Switzer- climate change, support the continued need to document land), marking the beginning of the world’s longest series stratospheric ozone changes. This is particularly valuable at of total (or column) ozone measurements. They were driven the Arosa site, due to the unique length of the observational by the recognition that atmospheric ozone is important for record. This paper presents the evolution of the ozone layer, human health, as well as by scientific curiosity about what the history of international ozone research, and discusses the was, at the time, an ill characterised atmospheric trace gas. justification for the measurements in the past, present and From around the mid-1950s to the beginning of the 1970s into future. studies of high atmosphere circulation patterns that could improve weather forecasting was justification for studying stratospheric ozone. In the mid-1970s, a paradigm shift oc- curred when it became clear that the damaging effects of 1 Introduction anthropogenic ozone-depleting substances (ODSs), such as long-lived chlorofluorocarbons, needed to be documented. -

Davos Im Portrait

Titel_Titel 21.06.13 08:36 Seite 1 Davos im Portrait Eine Information der Gemeinde Davos Eine Information der Gemeinde Davos Davos im Portrait – Davos US2_Willkomm 21.06.13 08:38 Seite 1 Davos_2013_Willkomm 21.06.13 11:35 Seite 1 Davos im Portrait | Vorwort 1 Vorwort Davos, ein besonders lebenswerter und erlebnisreicher Ort Am 1.Januar 2013 habe ich mit viel Freude mein neues Eine Dienstleistung ist auch dieses Nachschlagewerk Amt als Davoser Landammann angetreten. Eine Auf- – geschrieben für unsere Mitbürgerinnen und Mit- gabe, die vielfältiger kaum sein könnte, wie die Bro- bür ger sowie für unsere Gäste. Ein Geschenk und schüre «Davos im Portrait» gut dokumentiert. zu gleich eine Visitenkarte der Gemeinde Davos. In den ersten Monaten stellten mir Journalisten immer «Davos im Portrait» gibt unserer Gemeinde ein Ge- wieder folgende Frage: «Welches sind die grössten sicht, zeigt Ihnen unsere Welt auf über 1500 Metern Herausforderungen für Davos?» Für meine Antwort Höhe. Wer sich darin vertieft, wird staunen, wie viel- musste ich nicht lange nachdenken: Unsere grösste fältig und überraschend die Welt hier in den Bergen Herausforderung ist es, Davos als lebenswerten Ort ist. für Einheimische zu erhalten – und ihn gleichzeitig als erlebnisreiche Destination für Gäste aus aller Welt Lassen Sie uns gemeinsam Freude haben an diesem zu positionieren. nützlichen Nachschlagewerk. Und lassen Sie uns ge- meinsam an der Zukunft von Davos arbeiten. Ein Davos ist eine Gemeinde und eine Weltmarke zu - Davos für Einheimische und Gäste – besonders le- gleich, ein Ort mit einer grossen Geschichte und einer bens wert und erlebnisreich zugleich. faszinierenden Zukunft. Dabei ist Davos nicht nur Wohnort für 13 000 Frauen, Männer, Jugendliche und Kin der, sondern zudem ein «Erleb nis mittel punkt» – eine attraktive Landschaft also, die in der Hochsaison bis zu 60 000 Gäste anlockt. -

910 Landquart – Davos Platz Landquart – Vereina – Scuol-Tarasp Landquart – Vereina – St

FAHRPLANJAHR 2020 910 Landquart – Davos Platz Landquart – Vereina – Scuol-Tarasp Landquart – Vereina – St. Moritz Stand: 12. März 2020 R RE R R R R RE R RE RE 4307 4011 1912 1013 4213 1015 1017 1217 1021 1221 St. Moritz Scuol-Tarasp Scuol-Tarasp [Untervaz- Disentis/ Sagliains Trimmis] Mustér Landquart 4 55 5 13 5 34 6 20 6 47 7 47 7 50 Malans 5 37 6 22 6 50 7 53 Seewis-Pardisla 5 43 6 27 6 54 Grüsch 5 45 6 29 6 56 7 54 Schiers 5 26 5 50 6 33 7 00 7 59 8 03 Furna 5 57 6 37 7 04 Jenaz 6 00 6 39 7 06 8 08 Fideris 6 02 6 41 7 09 Küblis 5 15 5 39 6 08 6 46 7 14 8 10 8 14 Saas im Prättigau 5 46 6 13 6 51 7 19 8 20 Klosters Dorf 5 54 6 23 6 59 7 27 8 23 Klosters Platz 5 29 5 57 6 25 7 02 7 30 8 26 8 30 Klosters Platz 5 30 5 58 6 27 6 30 7 03 7 32 7 33 8 29 8 32 Cavadürli 6 05 6 33 8 35 Davos Laret 6 14 6 40 7 15 8 42 Davos Wolfgang 6 19 6 45 7 20 8 47 Davos Dorf 6 30 6 52 7 26 7 54 8 53 Davos Platz 6 33 6 57 7 29 7 57 8 57 Sagliains 6 01 6 57 7 58 8 54 Lavin 6 03 6 59 8 00 8 58 Guarda 6 07 7 04 8 04 9 02 Ardez 6 12 7 09 8 09 9 07 Ftan Baraigla 6 18 7 15 8 15 Scuol-Tarasp 6 23 7 18 8 19 9 15 Sagliains Susch 5 53 Zernez 6 02 Cinuos-chel-Brail 6 13 S-chanf 6 19 Zuoz 6 22 Madulain La Punt-Chamues-ch Bever 6 31 Samedan 6 34 Samedan 6 36 Celerina 6 39 St. -

Information for Day Guests Igloo-Village Davos Klosters

Information for day guests Igloo-village DavoS KloSTERS Please read this document carefully in order to be properly prepared for the Igloo-Village experience. Davos Klosters: a region full of opportunities with a varied range of activities, set in the middle of the beautiful Landwasser Valley but still easy to reach. Our Igloo-Village at Parsenn/Weissfluhjoch – at an altitude of 2,550m – is a pure natural idyll nestling above the traditional Graubünden holiday paradise of Davos, a pulsating leisure destination with over 10,000 inhabitants and more than 20,000 guest beds, itself 1,560m above sea level. During your journey The igloo-village Davos Klosters is located at the Parsenn / Weissfluhjoch skiresort. Please consider that the cable car journey takes about 30 minutes and the hike to the igloo-village takes another 20 minutes. For activities with a fixed starting time, any claim to forfeited services and refund shall lapse if arrival is more than 30 minutes late. This also applies to bookings with adventure vouchers. If you are late, please let us know immediately on +41 41 612 27 28. Please have the mobile phone you specified on reservation with you, so that we can contact you if needed (especially Equipment during your outward journey). The Igloo-Village nestles in the heart of nature on the mountain. Make sure you are properly Ascent & mountain railway tickets equipped. Normally the temperatures in the Igloo-Village remain constant at around freezing. The railway station at Davos-Dorf is easy and simple to get to by train. From Davos-Dorf railway station, the valley station of Parsennbahn is about five minutes’ walk. -

Read the New Bike Brochure

The single track paradise of the Alps davos.ch/bike klosters.ch/bike facebook.com/DavosKlostersBike schmiedi76 ... Felsenweg MEET YOUR instagram.com/DavosKlosters COMMUNITY schmiedi76 #bikedavos #bikebalance nadj.c ... ... Davos Klosters stay_wild_and_stay_free Davos Klosters manuelcaduff ... Davos Platz ... dari_ator Sertigtal nadj.c #davosklostersbike #ridenowsleeplater #davosklostersbike stay_wild_and_stay_free #mtbaddict manuelcaduff #davosklostersbike #rideordie #davosklosters #girlsshredtoo dari_ator Drei Tage unter Strom Drei Tage unter Strom Three days under powerpower Higher, faster, further: true to the motto ‘Expand your limits’, our photo story shows the new possibilities with an e-bike for an ultimate hut tour in Davos Klosters. When you’re used to doing things a certain way, it’s hard to switch, even if there’s an easier alternative. That’s how I felt about e-bikes, but I was pleasantly surprised. For a long time, e-bikes were seen as not sporty, too heavy, or just for old folks. But this view- point is outdated, and the reputation of e-bikes has done an about face. Even Danny MacAskill’s latest video has him riding an e-bike. Suddenly, there’s a whole new world of opportunity: Thanks to “uphill flow”, steep climbs are a piece of cake, and a day trip becomes a quick evening spin. Even long rides to get to the flowingest single-track trails are over in no time. Totally dope These words are as fitting for a Davos Klosters e-bike mountain hut tour as a fine-tuned SRAM XX1 trigger shifter on your dream bike. Because once we were a few kilometers into our ride down the Flüelatal and up to Tschuggen, things got pretty dope. -

Küblis: Klein Und Fein, Direkt Vor Davos Klosters

Profi tieren und mehr erleben mit der Davos Klosters Card Mit der Davos Klosters Card profi tieren auch Gäste in Küblis Küblis: Klein und fein, das ganze Jahr von zahlreichen Gratisleistungen und Preis- vergünstigungen. direkt vor Davos Klosters Die Davos Klosters Card gilt gleichzeitig auch als Bergbahn- ticket für freie Fahrt auf allen Bergbahnen im Sommer (im Rahmen des Angebots). Im Prättigau, unmittelbar vor der Ferien-Destination Davos Alle Leistunten unter: Klosters, an der Grand Tour of davos.ch/sommer/aktivitaeten/davos-klosters-inclusive Switzerland, liegt die Gemeinde Küblis (814 m ü. M.). Küblis ist ein kleines aber feines Dorf, Gut erschlossen mit öffentlichen Verkehrsmitteln das den Gästen beste Voraus- Küblis ist mit der Rhätischen Bahn rasch und bequem zu erreichen. Ebenso setzungen für Ruhe und Erho- einfach fahren Sie von Küblis aus mit Bahn und Postauto in die nähere und lung bietet. Dies insbesondere weitere Umgebung. nach der im Juni 2016 eröffne- ten Umfahrungsstrasse. Mit der Rhätischen Bahn RhB Küblis – Landquart – Chur Das Ortsbild von Küblis wird Küblis – Klosters – Davos dominiert von zwei auffälligen Küblis – Klosters – Scuol / Tarasp und markanten Bauten: Zum einen von der Evangelischen Kirche von 1491. Zum Küblis – Klosters – St. Moritz anderen vom mächtigen Kraftwerk des Stromdienstleisters Repower aus dem Jahre 1922. Der alte Dorfkern beheimatet noch einige ursprüngliche Herrschafts- Mit dem Postauto und Bauernhäuser. Küblis – Luzein – Pany – St. Antönien Küblis – Fideris – Jenaz – Furna oder Im Sommer führt die nationale Fahrrad/Bike-Route von Landquart nach Klos- Jenaz – Schiers ters/Davos durch Küblis. Für Wanderer stehen zahlreiche Wege und Routen im Küblis – Conters Tal oder in der Höhe zur Verfügung, z.B.