Do Atmospheric Events Explain the Arrival of an Invasive Ladybird

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ladybirds, Ladybird Beetles, Lady Beetles, Ladybugs of Florida, Coleoptera: Coccinellidae1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. EENY-170 Ladybirds, Ladybird beetles, Lady Beetles, Ladybugs of Florida, Coleoptera: Coccinellidae1 J. H. Frank R. F. Mizell, III2 Introduction Ladybird is a name that has been used in England for more than 600 years for the European beetle Coccinella septempunctata. As knowledge about insects increased, the name became extended to all its relatives, members of the beetle family Coccinellidae. Of course these insects are not birds, but butterflies are not flies, nor are dragonflies, stoneflies, mayflies, and fireflies, which all are true common names in folklore, not invented names. The lady for whom they were named was "the Virgin Mary," and common names in other European languages have the same association (the German name Marienkafer translates Figure 1. Adult Coccinella septempunctata Linnaeus, the to "Marybeetle" or ladybeetle). Prose and poetry sevenspotted lady beetle. Credits: James Castner, University of Florida mention ladybird, perhaps the most familiar in English being the children's rhyme: Now, the word ladybird applies to a whole Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home, family of beetles, Coccinellidae or ladybirds, not just Your house is on fire, your children all gone... Coccinella septempunctata. We can but hope that newspaper writers will desist from generalizing them In the USA, the name ladybird was popularly all as "the ladybird" and thus deluding the public into americanized to ladybug, although these insects are believing that there is only one species. There are beetles (Coleoptera), not bugs (Hemiptera). many species of ladybirds, just as there are of birds, and the word "variety" (frequently use by newspaper 1. -

COLEOPTERA COCCINELLIDAE) INTRODUCTIONS and ESTABLISHMENTS in HAWAII: 1885 to 2015

AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE COCCINELLID (COLEOPTERA COCCINELLIDAE) INTRODUCTIONS AND ESTABLISHMENTS IN HAWAII: 1885 to 2015 JOHN R. LEEPER PO Box 13086 Las Cruces, NM USA, 88013 [email protected] [1] Abstract. Blackburn & Sharp (1885: 146 & 147) described the first coccinellids found in Hawaii. The first documented introduction and successful establishment was of Rodolia cardinalis from Australia in 1890 (Swezey, 1923b: 300). This paper documents 167 coccinellid species as having been introduced to the Hawaiian Islands with forty-six (46) species considered established based on unpublished Hawaii State Department of Agriculture records and literature published in Hawaii. The paper also provides nomenclatural and taxonomic changes that have occurred in the Hawaiian records through time. INTRODUCTION The Coccinellidae comprise a large family in the Coleoptera with about 490 genera and 4200 species (Sasaji, 1971). The majority of coccinellid species introduced into Hawaii are predacious on insects and/or mites. Exceptions to this are two mycophagous coccinellids, Calvia decimguttata (Linnaeus) and Psyllobora vigintimaculata (Say). Of these, only P. vigintimaculata (Say) appears to be established, see discussion associated with that species’ listing. The members of the phytophagous subfamily Epilachninae are pests themselves and, to date, are not known to be established in Hawaii. None of the Coccinellidae in Hawaii are thought to be either endemic or indigenous. All have been either accidentally or purposely introduced. Three species, Scymnus discendens (= Diomus debilis LeConte), Scymnus ocellatus (=Scymnobius galapagoensis (Waterhouse)) and Scymnus vividus (= Scymnus (Pullus) loewii Mulsant) were described by Sharp (Blackburn & Sharp, 1885: 146 & 147) from specimens collected in the islands. There are, however, no records of introduction for these species prior to Sharp’s descriptions. -

(Ceroplastes Destructor) and Chinese Wax Scale (C. Sinesis) (Hemi

POPULATION ECOLOGY AND INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT OF SOFT WAX SCALE (CEROPLASTES DESTRUCTOR) AND CHINESE WAX SCALE (C. SINENSIS) (HEMIPTERA: COCCIDAE) ON CITRUS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Lincoln University Peter L. La Lincoln University 1994 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. POPUlATION ECOWGY AND INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT OF SOFT WAX SCALE (CEROPLASTES DESTRUCTOR) AND CHINESE WAX SCALE (c. SINENSIS) (HEMIPTERA: COCCIDAE) ON CITRUS Peter L. La Soft wax scale (SWS) Ceroplastes destructor (Newstead) and Chinese wax scale (CWS) C. sinensis Del Guercio (Hemiptera: Coccidae) are indirect pests of citrus (Citrus spp.) in New Zealand. Honeydew they produce supports sooty mould fungi that disfigure fruit and reduce photosynthesis and fruit yield. Presently, control relies on calendar applications of insecticides. The main aim of this study was to provide the ecological basis for the integrated management of SWS and CWS. Specific objectives were to compare their population ecologies, determine major mortality factors and levels of natural control, quantify the impact of ladybirds on scale populations, and evaluate pesticides for compatibility with ladybirds. Among 57 surveyed orchards, SWS was more abundant than CWS in Kerikeri but was not found around Whangarei. Applications of organophosphates had not reduced the proportion of orchards with medium or high densities of SWS. Monthly destructive sampling of scale populations between November 1990 and February 1994 was supplemented by in situ counts of scale cohorts. Both species were univoltine, but SWS eggs hatched two months earlier than those of CWS, and development between successive instars remained two to three months ahead. -

Phylogeny of Ladybirds (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae): Are the Subfamilies Monophyletic?

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 54 (2010) 833–848 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogeny of ladybirds (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae): Are the subfamilies monophyletic? A. Magro a,b,1, E. Lecompte b,c,*,1, F. Magné b,c, J.-L. Hemptinne a,b, B. Crouau-Roy b,c a Université de Toulouse, ENFA, EDB (Laboratoire Evolution et Diversité Biologique), 2 route de Narbonne, F-31320 Castanet Tolosan, France b CNRS, EDB (Laboratoire Evolution et Diversité Biologique), F-31062 Toulouse, France c Université de Toulouse, UPS, EDB (Laboratoire Evolution et Diversité Biologique), 118 route de Narbonne, F-31062 Toulouse, France article info abstract Article history: The Coccinellidae (ladybirds) is a highly speciose family of the Coleoptera. Ladybirds are well known Received 20 April 2009 because of their use as biocontrol agents, and are the subject of many ecological studies. However, little Revised 15 October 2009 is known about phylogenetic relationships of the Coccinellidae, and a precise evolutionary framework is Accepted 16 October 2009 needed for the family. This paper provides the first phylogenetic reconstruction of the relationships Available online 10 November 2009 within the Coccinellidae based on analysis of five genes: the 18S and 28S rRNA nuclear genes and the mitochondrial 12S, 16S rRNA and cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) genes. The phylogenetic relation- Keywords: ships of 67 terminal taxa, representative of all the subfamilies of the Coccinellidae (61 species, 37 genera), Phylogeny and relevant outgroups, were reconstructed using multiple approaches, including Bayesian inference Coccinellidae Partitioned analyses with partitioning strategies. The recovered phylogenies are congruent and show that the Coccinellinae Evolution is monophyletic but the Coccidulinae, Epilachninae, Scymninae and Chilocorinae are paraphyletic. -

Wikipedia Beetles Dung Beetles Are Beetles That Feed on Feces

Wikipedia beetles Dung beetles are beetles that feed on feces. Some species of dung beetles can bury dung times their own mass in one night. Many dung beetles, known as rollers , roll dung into round balls, which are used as a food source or breeding chambers. Others, known as tunnelers , bury the dung wherever they find it. A third group, the dwellers , neither roll nor burrow: they simply live in manure. They are often attracted by the dung collected by burrowing owls. There are dung beetle species of different colours and sizes, and some functional traits such as body mass or biomass and leg length can have high levels of variability. All the species belong to the superfamily Scarabaeoidea , most of them to the subfamilies Scarabaeinae and Aphodiinae of the family Scarabaeidae scarab beetles. As most species of Scarabaeinae feed exclusively on feces, that subfamily is often dubbed true dung beetles. There are dung-feeding beetles which belong to other families, such as the Geotrupidae the earth-boring dung beetle. The Scarabaeinae alone comprises more than 5, species. The nocturnal African dung beetle Scarabaeus satyrus is one of the few known non-vertebrate animals that navigate and orient themselves using the Milky Way. Dung beetles are not a single taxonomic group; dung feeding is found in a number of families of beetles, so the behaviour cannot be assumed to have evolved only once. Dung beetles live in many habitats , including desert, grasslands and savannas , [9] farmlands , and native and planted forests. They are found on all continents except Antarctica. They eat the dung of herbivores and omnivores , and prefer that produced by the latter. -

Beetles in a Suburban Environment: a New Zealand Case Study. The

tl n brbn nvrnnt: lnd td tl n brbn nvrnnt: lnd td h Idntt nd tt f Clptr n th ntrl nd dfd hbtt f nfld Alnd (4-8 GKhl . : rh At SI lnt rttn Mnt Albrt rh Cntr rvt Alnd lnd • SI lnt rttn prt • EW EAA EAME O SCIEIIC A IUSIA ESEAC 199 O Ο Ν Ε W Ε Ν ttr Grnt rd Τ Ε Ρ Ο Ι Ο Τ ie wi e suo o a oey Sciece eseac Ga om e ew eaa oey Gas oa is suo is gaeuy ackowege Ρ EW EAA SI ' EAME O lnt SCIEIIC A rttn IUSIA Wāhn ESEAC Mn p Makig Sciece Wok o ew eaa KUSCE G eees i a suua eiome a ew eaa case suy e ieiy a saus o Coeoea i e aua a moiie aias o yie Aucka (197-199 / G Kusce — Aucka SI 199 (SI a oecio eo ISS 11-1 ; o3 IS -77-59- I ie II Seies UC 5957(93111 © Cow Coyig uise y SI a oecio M Ae eseac Cee iae ag Aucka ew eaa eceme 199 ie y Geea iig Seices eso ew eaa Etiam pristina in aua Asο i a aua seig summa securitas et futura sweet tranquility and nature ., OISIECE e oe-eeig emoyci eee ioycus uuus (ou o is aie ooca os kaikaea (acycaus acyioies om e yie eee suey aea Aucka ew eaa e wie gaues o e eee ae oe cuses a ass ees is eee as a eic saus o uike a o e uaaa (Seoo as ossi eiece sows a e weei gou was iig i uassic imes way ack i e ea o e iosaus a gymosems moe a 1 miio yeas ago OEWO As a small boy in the 1930s I used to collect butterflies on the South Downs in southern England. -

IOBC Internet Book of Biological Control – Draft September 2005

IOBC Internet Book of Biological Control Version 5, January 2008 IOBC Internet Book of Biological Control, version 5 Editor: J.C. van Lenteren ([email protected]) Aim: to present the history, the current state of affairs and the future of biological control in order to show that this control method is sound, safe and sustainable Contents 1. Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Discovery of natural enemies and a bit of entomological history ..................................................................... 10 3. Development of idea to use natural enemies for pest control and classification of types of biological control 16 4. History of biological control ............................................................................................................................. 22 5. Current situation of biological control (including region/country revieuws).................................................... 41 6. Biological control of weeds .............................................................................................................................. 51 7. Future of biological control: to be written ........................................................................................................ 61 8. Mass production, storage, shipment and release of natural enemies................................................................. 62 9. Commercial and non-commercial producers -

Liste Des Coccinelles De Picar

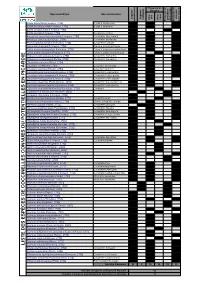

t s e n Présence en n a e e e d s o i s s s n i n e Picardie r e e e e e c g o i é u c c é c c l t é h q - è è n n n - r i h C e Nom scientifique Nom vernaculaire p t o e e p p n c u i e t a u l t s o r s s l s s l o o s q c x t n é i é é e i E E d e r r e a r u p A H d P P a d Adalia bipunctata (Linnaeus, 1758) Adalie à deux points 1 1 1 Adalia decempunctata (Linnaeus, 1758) Adalie à dix points 1 1 1 Adalia conglomerata (Linnaeus, 1758) 1 1 Anatis ocellata (Linnaeus, 1758) Coccinelle ocellée 1 1 1 Anisosticta novemdecimpunctata (Linnaeus, 1758) Coccinelle des roseaux 1 1 1 Aphidecta obliterata (Linnaeus, 1758) Coccinelle de l'épicea 1 1 1 Brumus quadripustulatus (Linnaeus, 1758) Coccinelle à virgule 1 1 1 Calvia decemguttata (Linnaeus, 1758) Calvia à dix points blancs 1 1 1 Calvia quatuordecimguttata (Linnaeus, 1758) Calvia à quatorze points blancs 1 1 1 Calvia quindecimguttata (Fabricius, 1777) Calvia à quinze points blancs 1 1 E Chilocorus bipustulatus (Linnaeus, 1758) Coccinelle des landes 1 1 1 I Chilocorus renipustulatus (Scriba, 1790) Coccinelle des saules 1 1 1 D Clitostethus arcuatus (Rossi, 1794) 1 1 1 R Coccidula rufa (Herbst, 1783) Coccidule des marais 1 1 1 A Coccidula scutellata (Herbst, 1783) Coccidule tachetée 1 1 1 C I Coccinella septempunctata (Linnaeus, 1758) Coccinelle à sept points 1 1 1 P Coccinella undecimpunctata (Linnaeus, 1758) Coccinelle à onze points 1 1 1 N Coccinella hieroglyphica (Linnaeus, 1758) Coccinelle à hiéroglyphe 1 1 E Coccinella magnifica (Redtenbacher, 1843) Coccinelle des fourmilières 1 1 1 Coccinella -

Halona2021r.Pdf

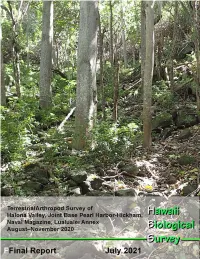

Terrestrial Arthropod Survey of Hālona Valley, Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Naval Magazine Lualualei Annex, August 2020–November 2020 Neal L. Evenhuis, Keith T. Arakaki, Clyde T. Imada Hawaii Biological Survey Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817, USA Final Report prepared for the U.S. Navy Contribution No. 2021-003 to the Hawaii Biological Survey EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Bishop Museum was contracted by the U.S. Navy to conduct surveys of terrestrial arthropods in Hālona Valley, Naval Magazine Lualualei Annex, in order to assess the status of populations of three groups of insects, including species at risk in those groups: picture-winged Drosophila (Diptera; flies), Hylaeus spp. (Hymenoptera; bees), and Rhyncogonus welchii (Coleoptera; weevils). The first complete survey of Lualualei for terrestrial arthropods was made by Bishop Museum in 1997. Since then, the Bishop Museum has conducted surveys in Hālona Valley in 2015, 2016–2017, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020. The current survey was conducted from August 2020 through November 2020, comprising a total of 12 trips; using yellow water pan traps, pitfall traps, hand collecting, aerial net collecting, observations, vegetation beating, and a Malaise trap. The area chosen for study was a Sapindus oahuensis grove on a southeastern slope of mid-Hālona Valley. The area had potential for all three groups of arthropods to be present, especially the Rhyncogonus weevil, which has previously been found in association with Sapindus trees. Trapped and collected insects were taken back to the Bishop Museum for sorting, identification, data entry, and storage and preservation. The results of the surveys proved negative for any of the target groups. -

An Annotated Checklist of Ladybeetle Species (Coleoptera, Coccinellidae) of Portugal, Including the Azores and Madeira Archipelagos

ZooKeys 1053: 107–144 (2021) A peer-reviewed open-access journal doi: 10.3897/zookeys.1053.64268 RESEARCH ARTICLE https://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research An annotated checklist of ladybeetle species (Coleoptera, Coccinellidae) of Portugal, including the Azores and Madeira Archipelagos António Onofre Soares1, Hugo Renato Calado2, José Carlos Franco3, António Franquinho Aguiar4, Miguel M. Andrade5, Vera Zina3, Olga M.C.C. Ameixa6, Isabel Borges1, Alexandra Magro7,8 1 Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes and Azorean Biodiversity Group, Faculty of Sci- ences and Technology, University of the Azores, 9500-321, Ponta Delgada, Portugal 2 Azorean Biodiversity Group, Faculty of Sciences and Technology, University of the Azores, 9501-801, Ponta Delgada, Portugal 3 Centro de Estudos Florestais (CEF), Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, 1349-017, Lisboa, Portugal 4 Laboratório de Qualidade Agrícola, Caminho Municipal dos Caboucos, 61, 9135-372, Camacha, Madeira, Portugal 5 Rua das Virtudes, Barreiros Golden I, Bloco I, R/C B, 9000-645, Funchal, Madeira, Portugal 6 Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies and Department of Biology, University of Aveiro, Campus Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193, Aveiro, Portugal 7 Laboratoire Evolution et Diversité biologique, UMR 5174 CNRS, UPS, IRD, 118 rt de Narbonne Bt 4R1, 31062, Toulouse cedex 9, France 8 University of Toulouse – ENSFEA, 2 rt de Narbonne, Castanet-Tolosan, France Corresponding author: António Onofre Soares ([email protected]) Academic editor: J. Poorani | Received 10 February 2021 | Accepted 24 April 2021 | Published 2 August 2021 http://zoobank.org/79A20426-803E-47D6-A5F9-65C696A2E386 Citation: Soares AO, Calado HR, Franco JC, Aguiar AF, Andrade MM, Zina V, Ameixa OMCC, Borges I, Magro A (2021) An annotated checklist of ladybeetle species (Coleoptera, Coccinellidae) of Portugal, including the Azores and Madeira Archipelagos. -

Contribution to the Knowledge of the Coccinellidae of Sardinia (Coleoptera) *

ConservaZione habitat invertebrati 5: 501–516 (2011) Cnbfvr Contribution to the knowledge of the Coccinellidae of Sardinia ( Coleoptera)* Claudio CANEPARI Via Venezia 1, I-20097 San Donato Milanese (MI), Italy. E-mail: [email protected] *In: Nardi G., Whitmore D., Bardiani M., Birtele D., Mason F., Spada L. & Cerretti P. (eds), Biodiversity of Marganai and Montimannu (Sardinia). Research in the framework of the ICP Forests network. Conservazione Habitat Invertebrati, 5: 501–516. ABSTRACT An updated checklist of the Coccinellidae of Sardinia (Italy) is provided. Sixty-two species are recorded with certainty, while 19 other species (Scymnus (Mimopullus) fulvicollis (Mulsant, 1846), S. (M.) pharaonis Motschulsky, 1851, S. (Neopullus) haemorrhoidalis (Herbst, 1797), S. (N.) limbatus limbatus (Stephens, 1831), Nephus (Nephus) reunioni Fürsch, 1974, Scymniscus tristiculus (Weise, 1929), Hyperaspis chevrolati Canepari, 1985, H. concolor Suffrian, 1843, H. hoffmannseggi (Gravenhorst, 1807), H. reppensis reppensis (Herbst, 1783), Coc- cidula rufa (Herbst, 1783), Coccinella (Coccinella) magnifi ca Redtenbacher, 1843, Tytthaspis phalerata (A. Costa, 1849), Oenopia lyncea agnata (Rosenhauser, 1847), Halyzia sedecimguttata (Linnaeus, 1758), Myrrha octodecimguttata octodecimguttata (Linnaeus, 1758), Calvia decemguttata (Linnaeus, 1758), Chilocorus similis (Rossi, 1790) and Exochomus nigromaculatus (Goeze, 1777)) are excluded from the Sardinian fauna. Key words: Coccinellidae, Sardinia, faunistics, new records, checklist. RIASSUNTO Contributo alla conoscenza dei Coccinellidae della Sardegna (Coleoptera) L'autore fornisce una lista aggiornata dei Coccinellidae di Sardegna; complessivamente sono segnalate con certezza 62 specie, mentre altre 19 specie (Scymnus (Mimopullus) fulvicollis (Mulsant, 1846), S. (M.) pharaonis Motschulsky, 1851, S. (Neopullus) haemorrhoidalis (Herbst, 1797), S. (N.) limbatus limbatus (Stephens, 1831), Nephus (Nephus) reunioni Fürsch, 1974, Scymniscus tristiculus (Weise, 1929), Hyperaspis chevrolati Canepari, 1985, H. -

Technical Report 148

PACIFIC COOPERATIVE STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I AT MĀNOA Dr. David C. Duffy, Unit Leader Department of Botany 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408 Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 Technical Report 148 INVENTORY OF ARTHROPODS OF THE WEST SLOPE SHRUBLAND AND ALPINE ECOSYSTEMS OF HALEAKALA NATIONAL PARK September 2007 Paul D. Krushelnycky 1,2, Lloyd L. Loope 2, and Rosemary G. Gillespie 1 1 Department of Environmental Science, Policy & Management, 137 Mulford Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA, 94720-3114 2 U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, Haleakala Field Station, P.O. Box 369, Makawao, HI 96768 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………. 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………… 4 Methods……………………………………………………………………………..5 Results and Discusion……………………………………………………………….8 Literature Cited…………………………………………………………………….. 10 Table 1 – Summary of captures……………………………………………………. 14 Table 2 – Species captures in different elevational zones…………………………..15 Table 3 – Observed and estimated richness………………………………………... 16 Figure 1 – Sampling localities……………………………………………………... 17 Figure 2 – Species accumulation curves…………………………………………… 18 Appendix: Annotated list of arthropod taxa collected……………………………... 19 Class Arachnida……………………………………………………………. 20 Class Entognatha…………………………………………………………… 25 Class Insecta………………………………………………………………...26 Class Malacostraca………………………………………………………..... 51 Class Chilopoda……………………………………………………………. 51 Class Diplopoda……………………………………………………………. 51 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank first and foremost the many specialists who identified or confirmed identifications of many of our specimens, or helped by pointing us in the right direction. Without this help, an inventory of this nature would simply not be possible. These specialists include K. Arakaki, M. Arnedo, J. Beatty, K. Christiansen, G. Edgecombe, N. Evenhuis, C. Ewing, A. Fjellberg, V. Framenau, J. Garb, W. Haines, S. Hann, J. Heinze, F. Howarth, B. Kumashiro, J. Liebherr, I. MacGowan, K. Magnacca, S.