!"', I, Attic Prose: Lipsius, Montaigne, Bacon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

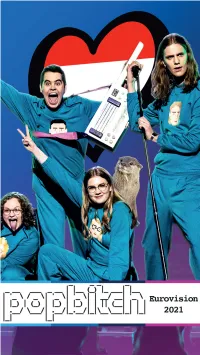

Template EUROVISION 2021

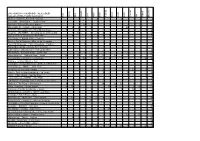

Write the names of the players in the boxes 1 to 4 (if there are more, print several times) - Cross out the countries that have not reached the final - Vote with values from 1 to 12, or any others that you agree - Make the sum of votes in the "TOTAL" column - The player who has given the highest score to the winning country will win, and in case of a tie, to the following - Check if summing your votes you’ve given the highest score to the winning country. GOOD LUCK! 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Anxhela Peristeri “Karma” Albania Montaigne “ Technicolour” Australia Vincent Bueno “Amen” Austria Efendi “Mata Hari” Azerbaijan Hooverphonic “ The Wrong Place” Belgium Victoria “Growing Up is Getting Old” Bulgaria Albina “Tick Tock” Croatia Elena Tsagkrinou “El diablo” Cyprus Benny Christo “ Omaga “ Czech Fyr & Flamme “Øve os på hinanden” Denmark Uku Suviste “The lucky one” Estonia Blind Channel “Dark Side” Finland Barbara Pravi “Voilà” France Tornike Kipiani “You” Georgia Jendrick “I Don’t Feel Hate” Germany Stefania “Last Dance” Greece Daði og Gagnamagnið “10 Years” Island Leslie Roy “ Maps ” Irland Eden Alene “Set Me Free” Israel 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Maneskin “Zitti e buoni” Italy Samantha Tina “The Moon Is Rising” Latvia The Roop “Discoteque” Lithuania Destiny “Je me casse” Malta Natalia Gordienko “ Sugar ” Moldova Vasil “Here I Stand” Macedonia Tix “Fallen Angel” Norwey RAFAL “The Ride” Poland The Black Mamba “Love is on my side” Portugal Roxen “ Amnesia “ Romania Manizha “Russian Woman” Russia Senhit “ Adrenalina “ San Marino Hurricane “LOCO LOCO” Serbia Ana Soklic “Amen” Slovenia Blas Cantó “Voy a quedarme” Spain Tusse “ Voices “ Sweden Gjon’s Tears “Tout L’Univers” Switzerland Jeangu Macrooy “ Birth of a new age” The Netherlands Go_A ‘Shum’ Ukraine James Newman “ Embers “ United Kingdom. -

Francis Bacon: of Law, Science, and Philosophy Laurel Davis Boston College Law School, [email protected]

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Rare Book Room Exhibition Programs Daniel R. Coquillette Rare Book Room Fall 9-1-2013 Francis Bacon: Of Law, Science, and Philosophy Laurel Davis Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/rbr_exhibit_programs Part of the Archival Science Commons, European History Commons, and the Legal History Commons Digital Commons Citation Davis, Laurel, "Francis Bacon: Of Law, Science, and Philosophy" (2013). Rare Book Room Exhibition Programs. Paper 20. http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/rbr_exhibit_programs/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daniel R. Coquillette Rare Book Room at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rare Book Room Exhibition Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Francis Bacon: Of Law, Science, and Philosophy Boston College Law Library Daniel R. Coquillette Rare Book Room Fall 2013 This exhibit was curated by Laurel Davis and features a selection of books from a beautiful and generous gift to us from J. Donald Monan Professor of Law Daniel R. Coquillette The catalog cover was created by Lily Olson, Law Library Assistant, from the frontispiece portrait in Bacon’s Of the Advancement and Proficiencie of Learn- ing: Or the Partitions of Sciences Nine Books. London: Printed for Thomas Williams at the Golden Ball in Osier Lane, 1674. The caption of the original image gives Bacon’s official title and states that he died in April 1626 at age 66. -

![Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -In Memoriam]Ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7141/montaignes-unknown-god-and-melvilles-confidence-man-in-memoriam-ohn-spencer-hill-1943-1998-977141.webp)

Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -In Memoriam]Ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998)

CAMILLE R. LA Bossr:ERE The World Revolves Upon an I: Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -in memoriam]ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998) Les mestis qui ont ... le cul entre deux selles, desquels je suis ... I The mongrel! sorte, of which I am one ... sit betweene two stooles -Michel de Montaigne, "Des vaines subtilitez" I "Of Vaine Subtilties" Deus est anima brutorum. -Oliver Goldsmith, "The Logicians Refuted" YEA AND NAY EACH HATH HIS SAY: BUT GOD HE KEEPS THF MTDDT.F WAY -Herman Melville, "The Conflict of Convictions" T ATE-MODERN SCHOLARLY accounts of Montaigne and his L oeuvre attest to the still elusive, beguilingly ironic character of his humanism. On the one hand, the author of the Essais has in vited recognition as "a critic of humanism, as part of a 'Counter Renaissance'."' The wry upending of such vanity as Protagoras served to model for Montaigne-"Truely Protagoras told us prettie tales, when he makes man the measure of all things, who never knew so much as his owne," according to the famous sentence 1 Peter Burke, Montaigne (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1981) 11. 340 • THE DALHOUSIE REvlEW from the "Apologie of Raimond Sebond"2-naturally comes to mind when he is thought of in this way (Burke 12). On the other hand, Montaigne has been no less justifiably recognized by a long line of twentieth-century commentators3 as a major contributor to the progress of an enduring philosophy "qui fait de l'homme, selon la tradition antique, la valeur premiere et vise a son plein epa nouissement. -

Of Building, Essay 45, Aus: FRANCIS BACON, the Essayes Or Counsels

FRANCIS BACON : Of Building , Essay 45, aus: FRANCIS BACON , The Essayes or Counsels, Civill and Morall, of Francis Lo. Verulam, Viscount St. Alban (London: Printed by Iohn Haviland for Hanna Barret, 1625) herausgegeben und eingeleitet von CHARLES DAVIS FONTES 16 [1. Oktober 2008] Zitierfähige URL: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/volltexte/2008/609 [Francis Bacon] THE E S S A Y E S OR C O V N S E L S, C I V I L L A N D M O R A L L, OF FRANCIS LO. VERVLAM, VISCOVNT S t. ALBAM. __________________________ Newly written . __________________________ __________________________ LONDON, Printed by I O H N H A V I L A N D, for H A N N A B A R R E T . 1625. Essay XLV. Of Building. , pp. 257-265 FONTES 16 1 Anon., Francis Bacon, Baron Verulam, Viscount St. Albans, engraving 2 CONTENTS 4 OUTLINE AND STRUCTURE of FRANCIS BACON’s Of Building 10 INTRODUCTION . “ A HOUSE IS TO LIVE IN, NOT TO LOOK AT ”: FRANCIS BACON’S ESSAY “OF BUILDING ”, 1625 13 ANTHOLOGY OF COMMENTARIES TO BACON’S Of Building 18 THE TEXT OF BACON’S Of Building 21 GLOSSARY OF BACON’S Of Building 26 ARCHITECTURAL PUBLICATIONS IN ENGLISH UNTIL 1625 28 BIOGRAPHY OF FRANCIS BACON 29 FRANCIS BACON: Bio-Bibliography 30 THE NEW ATLANTIS 32 THE DEDICATION OF THE “Newly written ” Essays to the Duke of Buckingham 34 LITERATURE ABOUT FRANCIS BACON 36 APPENDIX ONE: OF PLANTATIONS 38 APPENDIX TWO: OF BEAUTY 39 ‘NOTABLE THINGS’: Words, themes, topics, names, places in Of Building 3 OUTLINE and STRUCTURE of FRANCIS BACON’S Of Building Francis Bacon’s essay, Of Building , can perhaps be understood most directly by first examining its form and content synoptically. -

P E Ti Is Tv Á N O Rs I L Á S Z Ló L E V I a Ttila B E Tti P . R O B I

n e i s l b ó l e m n l i i o i i z u a f o z i i á i t s l b s t i t R ESC HUNGARY RAJONGÓI TALÁLKOZÓ c b s v ó s i v z t t t r s o e t e . r i s a á e s m 2021-08-28 HELYSZÍNI SZAVAZÁS P I O L L A B P E Z R T I P Ö Albánia – Anxhela Peristeri – Karma 3 2 1 3 9 Ausztrália – Montaigne – Technicolour 5 5 Ausztria – Vincent Bueno – Amen 10 2 2 14 Azerbajdzsán – Efendi – Mata Hari 1 1 5 8 7 10 6 38 Belgium – Hooverphonic – The Wrong Place 6 4 3 6 19 Bulgária – VICTORIA – Growing Up Is Getting Old 7 10 7 7 6 4 41 Ciprus – Elena Tsagrinou – El Diablo 3 4 3 3 4 3 2 22 Csehország – Benny Cristo – omaga 0 Dánia – Fyr & Flamme – Øve os på hinanden 1 1 Egyesült Királyság – James Newman – Embers 5 6 1 12 Észak-Macedónia – Vasil – Here I Stand 0 Észtország – Uku Suviste – The Lucky One 7 4 11 Finnország – Blind Channel – Dark Side 2 2 8 12 Franciaország – Barbara Pravi – Voilà 10 12 12 12 12 12 4 3 2 79 Görögország – Stefania – Last Dance 12 4 5 2 6 10 39 Grúzia – Tornike Kipiani – You 0 Hollandia – Jeangu Macrooy – Birth of a New Age 8 7 4 19 Horvátország – Albina – Tick-Tock 7 2 8 17 Írország – Lesley Roy – Maps 2 5 12 8 27 Izland – Daði og Gagnamagnið – 10 Years 7 6 3 5 1 22 Izrael – Eden Alene – Set Me Free 1 3 2 6 Lengyelország – RAFAŁ – The Ride 8 7 15 Lettország – Samanta Tīna – The Moon Is Rising 1 1 Litvánia – The Roop – Discoteque 4 5 8 10 10 10 4 51 Málta – Destiny – Je me casse 8 10 12 4 6 10 50 Moldova – Natalia Gordienko – Sugar 5 10 8 23 Németország – Jendrik – I Don’t Feel Hate 0 Norvégia – TIX – Fallen Angel 0 Olaszország – Måneskin -

Descriptions of Sections

Fall 2009 LEH300-LEH301 Descriptions LEH300 Anderson, Jazz and the Improvised Arts A history of jazz music from New Orleans to New York is coupled with an examination James of improvisation in the arts. The class will investigate form and free creativity as applied to jazz, music from around the world, the visual arts, drama, and literature. LEH300 Ansaldi, The Doctor-Patient Relationship: In this course, participants will explore the complexities of the doctor-patient Pamela Viewed through Art and Science relationship by examining selected works of literature, medicine, psychology and art. To the doctor, illness is an analysis of blood tests, radiological images and clinical observations. To the patient, illness is a disrupted life. To the doctor, the disease process must be measured and charted. To the patient, disease is unfamiliar terrain—he or she looks to the doctor to provide a compass. The doctor may give directions, but the patient for various reasons may not follow them. Or, the doctor may give the wrong directions, leaving the patient to wander in circles, feeling lost and alone. Sometimes two doctors can give identical protocols to the same patient, but only one doctor can provide a cure. The surgeon wants to cut out the injured part; the patient wants to retain it at any cost. The physician diagnoses with a linear understanding of illness; the patient may see the sequencing of events leading up to the illness in a different order, which might lead to a different diagnosis. The twists and turns of doctor-patient communication can be dizzying…and the patient goes from doctor to doctor seeking clarity and a possible cure. -

2021 Country Profiles

Eurovision Obsession Presents: ESC 2021 Country Profiles Albania Competing Broadcaster: Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSh) Debut: 2004 Best Finish: 4th place (2012) Number of Entries: 17 Worst Finish: 17th place (2008, 2009, 2015) A Brief History: Albania has had moderate success in the Contest, qualifying for the Final more often than not, but ultimately not placing well. Albania achieved its highest ever placing, 4th, in Baku with Suus . Song Title: Karma Performing Artist: Anxhela Peristeri Composer(s): Kledi Bahiti Lyricist(s): Olti Curri About the Performing Artist: Peristeri's music career started in 2001 after her participation in Miss Albania . She is no stranger to competition, winning the celebrity singing competition Your Face Sounds Familiar and often placed well at Kënga Magjike (Magic Song) including a win in 2017. Semi-Final 2, Running Order 11 Grand Final Running Order 02 Australia Competing Broadcaster: Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) Debut: 2015 Best Finish: 2nd place (2016) Number of Entries: 6 Worst Finish: 20th place (2018) A Brief History: Australia made its debut in 2015 as a special guest marking the Contest's 60th Anniversary and over 30 years of SBS broadcasting ESC. It has since been one of the most successful countries, qualifying each year and earning four Top Ten finishes. Song Title: Technicolour Performing Artist: Montaigne [Jess Cerro] Composer(s): Jess Cerro, Dave Hammer Lyricist(s): Jess Cerro, Dave Hammer About the Performing Artist: Montaigne has built a reputation across her native Australia as a stunning performer, unique songwriter, and musical experimenter. She has released three albums to critical and commercial success; she performs across Australia at various music and art festivals. -

AFTER the FACT Scripts & Postscripts

After the fact proof 1-19-16.qxp_Layout 1 7/13/16 3:31 PM Page 1 AFTER THE FACT Scripts & Postscripts After the fact proof 1-19-16.qxp_Layout 1 7/13/16 3:31 PM Page 2 After the fact proof 1-19-16.qxp_Layout 1 7/13/16 3:31 PM Page 3 AFTER THE FACT Scripts & Postscripts a Marvin Bell and Christopher Merrill White Pine Press / Buffalo, New York After the fact proof 1-19-16.qxp_Layout 1 7/13/16 3:31 PM Page 4 White Pine Press P.O. Box 236 Buffalo, New York 14201 www.whitepine.org Copyright © 2016 by Marvin Bell and Christopher Merrill All rights reserved. This work, or portions thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher. Publication of this book was made possible, in part, by grants from the Amazon Literary Partnership; the National Endowment for the Arts, which believes that a great nation deserves great art; with public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, a State Agency; and with the support of the Office of the Vice President of Research at The Uni - versity of Iowa. Acknowledgments: #1-10 Denver Quarterly #11-20 Conversations Across Borders #21-30 The Georgia Review #31-36 Ecotone #37-42 The Iowa Review #43-52 Prairie Schooner #53-58 Fiddlehead #59-60 december #61-70 The Georgia Review #71-80 december #81-90 The Georgia Review Cover image: “Against Perfection” by Sam Roderick Roxas-Chua, used by permission of the artist. -

Baconian Essays

Ex Libris C. K. OGDEN THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.arcliive.org/details/baconianessaysOOsmit BACONIAN ESSAYS BACONIAN ESSAYS BY E. W. SMITHSON WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND TWO ESSAYS BY SIR GEORGE GREENWOOD LONDON CECIL PALMER OAKLEY HOUSE, 14-18 BLOOMSBURY ST., W.C. i First Edition Copy- right 1922 CONTENTS PAGE Introductory (by G. Greenwood) ... 7 Five Essays by E. W. Smithson The Masque of "Time Vindicated" . 41 Shakespeare—A Theory . .69 Ben Jonson and Shakespeare . .97 " " Bacon and Poesy . 123 " The Tempest" and Its Symbolism . 149 Two Essays by G. Greenwood The Common Knowledge of Shakespeare and Bacon 161 The Northumberland Manuscript . 187 Final Note (G. G.) . , . 223 J /',-S ^ a.^'1-^U- a BACONIAN ESSAYS INTRODUCTORY Henry James, in a letter to Miss Violet Hunt, thus delivers himself with regard to the authorship of " " — the plays and poems of Shakespeare * : " I am * a sort of ' haunted by the conviction that the divine William is the biggest and most successful fraud ever practised on a patient world. The more I turn him round and round the more he so affects me." Now I do not for a moment suppose that in so writing the late Mr. Henry James had any intention of affixing the stigma of personal fraud upon William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon. Doubtless he used the term '* fraud " in a semi-jocular vein as we so often hear it made use of in the colloquial language of the present day, and his meaning is nothing more, and nothing less, than this, viz., that the beHef that the plays and poems of " Shake- speare " were, in truth and in fact, the work of " the man from Stratford," (as he subsequently, in the same letter, styles *' the divine William ") is one of the greatest of all the many delusions which have, * Letters of Henry James. -

There's a Common Misconception About Eurovision Songs

First Half Second Half The Stats The Rest Hello, Rotterdam! After a year in storage, it’s time to dust off Europe’s most peculiar pop tradition and watch as singers from every corner of the continent come to do battle. As ever, we’ve compiled a full guide to the most bizarre, brilliant and boring things the contest has to offer... ////////////////////////////////// The First Half...............3-17 Cypriot Satan worshipping! Homemade Icelandic indie-disco! 80s movie montages and gigantic Russian dolls! Unusually for Eurovision, the first half features some of this year’s hot favourites, so you’ll want to be tuned in from the start. The Second Half.............19-33 Finnish nu-metal! Angels with Tourette’s! A Ukrainian folk- rave that sounds like Enya double-dropping and Flo Fucking Rida! Things start getting a little bit weirder here, especially if you’re a few drinks in, but we’re here to hold your hand. The Stats...................34-42 Diagrams, facts, information, theory. You want to impress your mates with absolutely useless knowledge about which sorts of things win? We’ve got everything you need... The Ones We Left Behind.....43-56 If you didn’t catch the semis, you’ll have missed some mad stuff fall by the wayside. To honour those who tripped at the first hurdle, we’ve kept their profiles here for posterity – so you’ll never need ask “Who was the Polish Bradley Walsh?” First Half Second Half The Stats The Rest Pt.1: At A Glance The Grand Final’s first half is filled with all your classic Saturday night Europop staples. -

The World of Mathematics Volume 4

THE WORLD OF MATHEMATICS VOLUME IV Volume Four of THE WORLD OF MATHEMATICS A small library of the literature of mathematics from. A'h-mose the Scribe to Albert Einstein, presented with commentaries and notes by JAMES R. NEWMAN LONDON GEORGE ALLEN AND UNWIN LTD First Published in Great Britain in I960 This book is copyright under the Berne Convention, Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, atticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, 1956, no portion maybe reproduced by any process without writ fen permission. Enquiry should be made to the publisher. © James R. Newman 1956 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Editor wishes to express his gratitude for Mahomet", from What h Mathematics? by Richard permission to reprint ma le rial from the following Courant and Herbert Rabbins. sources: Philosophy of Sciertce, for "The Locus of Mathe- Messrs. John Lane. Ths Bodiey Head Ltd,, Tor matical Reality: An Anthropologics! Footnote", by "Common Sense and the Universe", by Stephen Leslie A. White, issue of October, 1947. Le acock. The Science Press for "Mathematical Creation", Professor R. L. Goodslein, and The Mathematics! from Foundations of Science, hy Henri Poincarc, Association for "Easy Mathematics and Lawn translated by George Bruce Haisted. Tennis" by T, J. LA. Bromwich, from Mathematical Scientific American, for "A Chess- Playing Gateite XI If, October, I92S, Machine", by Claude Shannon. Cambridge University Press for "Mathematics of Messrs. G. Bell & Sons Ltd., for "Pastimes of Music", from Science and Music, by Sir James Past and Present Times", from Mathematics and the Jeans; and for excerpt from A Mathematician's Imagination, by Edward Kasner and James R, Apology, by G. -

Rotterdam Hosts COVID-Safe Eurovision Song Contest

Slow Italian, Fast Learning Ep.162: Rotterdam hosts COVID-Safe Eurovision song contest Italian English Chanting sound effects, fade under VO Chanting sound effects, fade under VO L'artista russa Manizha Sangin sta Russian performer Manizha Sangin is scaldando le sue corde vocali in attesa warming up her vocal cords in preparation dell'Eurovision Song Contest. for the Eurovision Song Contest. Parteciperanno alla 65esima edizione 39 entrants will take part in the 65th della competizione 39 concorrenti, dopo competition being held after a year off la sospensione di un anno a causa della because of the coronavirus pandemic. pandemia di coronavius. La cantante Natalia Gordienko Singer Natalia Gordienko is representing rappresenta la Moldavia e l'autore russo Moldova and Russian song-writer Philipp Philipp Kirkorov le ha scritto la sua Kirkorov penned her tune, 'Sugar'. composizione, 'Sugar'. VO translation "We sing about love, joy "VO translation "We sing about love, joy and happiness that we want to bring to and happiness that we want to bring to life, for it to be as sweet as these life, for it to be as sweet as these candies that we love." candies that we love." FADE UNDER VO FADE UNDER VO L'artista Montaigne rappresenta l'Australia Artist Montaigne is representing Australia ma è rimasta a Sydney e verrà trasmessa but she's staying in Sydney and a una registrazione della sua esibizione. recording of her performance will be aired. Si è detta incerta su come la sua canzone She is unsure how her song 'Technicolour' 'Technicolour' possa venire recepita vista will be received when it's viewed on sul video invece che in diretta sul palco.