Verbal Usury in the Merchant of Venice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francis Bacon: of Law, Science, and Philosophy Laurel Davis Boston College Law School, [email protected]

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Rare Book Room Exhibition Programs Daniel R. Coquillette Rare Book Room Fall 9-1-2013 Francis Bacon: Of Law, Science, and Philosophy Laurel Davis Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/rbr_exhibit_programs Part of the Archival Science Commons, European History Commons, and the Legal History Commons Digital Commons Citation Davis, Laurel, "Francis Bacon: Of Law, Science, and Philosophy" (2013). Rare Book Room Exhibition Programs. Paper 20. http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/rbr_exhibit_programs/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daniel R. Coquillette Rare Book Room at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rare Book Room Exhibition Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Francis Bacon: Of Law, Science, and Philosophy Boston College Law Library Daniel R. Coquillette Rare Book Room Fall 2013 This exhibit was curated by Laurel Davis and features a selection of books from a beautiful and generous gift to us from J. Donald Monan Professor of Law Daniel R. Coquillette The catalog cover was created by Lily Olson, Law Library Assistant, from the frontispiece portrait in Bacon’s Of the Advancement and Proficiencie of Learn- ing: Or the Partitions of Sciences Nine Books. London: Printed for Thomas Williams at the Golden Ball in Osier Lane, 1674. The caption of the original image gives Bacon’s official title and states that he died in April 1626 at age 66. -

Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century

Global Positioning: Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wong, John. 2012. Global Positioning: Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9282867 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 – John D. Wong All rights reserved. Professor Michael Szonyi John D. Wong Global Positioning: Houqua and his China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century Abstract This study unearths the lost world of early-nineteenth-century Canton. Known today as Guangzhou, this Chinese city witnessed the economic dynamism of global commerce until the demise of the Canton System in 1842. Records of its commercial vitality and global interactions faded only because we have allowed our image of old Canton to be clouded by China’s weakness beginning in the mid-1800s. By reviving this story of economic vibrancy, I restore the historical contingency at the juncture at which global commercial equilibrium unraveled with the collapse of the Canton system, and reshape our understanding of China’s subsequent economic experience. I explore this story of the China trade that helped shape the modern world through the lens of a single prominent merchant house and its leading figure, Wu Bingjian, known to the West by his trading name of Houqua. -

The Merchant of Venice Theme: Exploring Shylock

Discovering Literature www.bl.uk/shakespeare Teachers’ Notes Curriculum subject: English Literature Key Stage: 4 and 5 Author / Text: William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice Theme: Exploring Shylock Rationale Shylock is one of Shakespeare’s most complex and troubling characters. He is marked from his very first appearance as an outsider in Venetian society, scorned and spat on by Christians and stripped of his wealth and religion. Nevertheless, he is also fuelled by vengeance. How are we to interpret Shylock as a character? Is he a stereotypical villain, or the victim of prejudice and racial hatred? These activities encourage students to explore the character of Shylock, setting him against the backdrop of myths and fears about Jews that existed in Shakespeare’s England. Students will examine some of the ways in which Shylock has been depicted on stage and will relate these different interpretations to changing cultural sensitivities. Content Literary and historical sources: Description of the Jewish Ghetto and the courtesans of Venice in Coryate's Crudities (1611) Doctor Lopez is accused of poisoning Elizabeth I (1627) The first illustrated works of Shakespeare edited by Nicholas Rowe (1709) Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta (1633) Henry Irving as Shylock and Ellen Terry as Portia (1906–10) Photographs of Yiddish production of The Merchant of Venice (1946) Recommended reading (short articles): How were the Jews regarded in 16th-century England?: James Shapiro A Jewish reading of The Merchant of Venice: Aviva Dautch External links: -

Revisiting Shakespeare's Problem Plays: the Merchant of Venice

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature REVISITING SHAKESPEARE’S PROBLEM PLAYS: THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, HAMLET AND MEASURE FOR MEASURE Emine Seda ÇAĞLAYAN MAZANOĞLU Ph.D. Dissertation Ankara, 2017 REVISITING SHAKESPEARE’S PROBLEM PLAYS: THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, HAMLET AND MEASURE FOR MEASURE Emine Seda ÇAĞLAYAN MAZANOĞLU Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature Ph.D. Dissertation Ankara, 2017 v For Hayriye Gülden, Sertaç Süleyman and Talat Serhat ÇAĞLAYAN and Emre MAZANOĞLU vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my endless gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Dr. A. Deniz BOZER for her great support, everlasting patience and invaluable guidance. Through her extensive knowledge and experience, she has been a model for me. She has been a source of inspiration for my future academic career and made it possible for me to recognise the things that I can achieve. I am extremely grateful to Prof. Dr. Himmet UMUNÇ, Prof. Dr. Burçin EROL, Asst. Prof. Dr. Şebnem KAYA and Asst. Prof. Dr. Evrim DOĞAN ADANUR for their scholarly support and invaluable suggestions. I would also like to thank Dr. Suganthi John and Michelle Devereux who supported me by their constant motivation at CARE at the University of Birmingham. They were the two angels whom I feel myself very lucky to meet and work with. I also would like to thank Prof. Dr. Michael Dobson, the director of the Shakespeare Institute and all the members of the Institute who opened up new academic horizons to me. I would like to thank Dr. -

Of Building, Essay 45, Aus: FRANCIS BACON, the Essayes Or Counsels

FRANCIS BACON : Of Building , Essay 45, aus: FRANCIS BACON , The Essayes or Counsels, Civill and Morall, of Francis Lo. Verulam, Viscount St. Alban (London: Printed by Iohn Haviland for Hanna Barret, 1625) herausgegeben und eingeleitet von CHARLES DAVIS FONTES 16 [1. Oktober 2008] Zitierfähige URL: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/volltexte/2008/609 [Francis Bacon] THE E S S A Y E S OR C O V N S E L S, C I V I L L A N D M O R A L L, OF FRANCIS LO. VERVLAM, VISCOVNT S t. ALBAM. __________________________ Newly written . __________________________ __________________________ LONDON, Printed by I O H N H A V I L A N D, for H A N N A B A R R E T . 1625. Essay XLV. Of Building. , pp. 257-265 FONTES 16 1 Anon., Francis Bacon, Baron Verulam, Viscount St. Albans, engraving 2 CONTENTS 4 OUTLINE AND STRUCTURE of FRANCIS BACON’s Of Building 10 INTRODUCTION . “ A HOUSE IS TO LIVE IN, NOT TO LOOK AT ”: FRANCIS BACON’S ESSAY “OF BUILDING ”, 1625 13 ANTHOLOGY OF COMMENTARIES TO BACON’S Of Building 18 THE TEXT OF BACON’S Of Building 21 GLOSSARY OF BACON’S Of Building 26 ARCHITECTURAL PUBLICATIONS IN ENGLISH UNTIL 1625 28 BIOGRAPHY OF FRANCIS BACON 29 FRANCIS BACON: Bio-Bibliography 30 THE NEW ATLANTIS 32 THE DEDICATION OF THE “Newly written ” Essays to the Duke of Buckingham 34 LITERATURE ABOUT FRANCIS BACON 36 APPENDIX ONE: OF PLANTATIONS 38 APPENDIX TWO: OF BEAUTY 39 ‘NOTABLE THINGS’: Words, themes, topics, names, places in Of Building 3 OUTLINE and STRUCTURE of FRANCIS BACON’S Of Building Francis Bacon’s essay, Of Building , can perhaps be understood most directly by first examining its form and content synoptically. -

A Žižekian Reading of the Jewish Question in the Merchant of Venice

CLEaR , 2016, 3(2), ISSN 2453 - 7128 DOI: 10.1515/clear - 2016 - 0011 “Which is the Merchant and which is the Jew?” a Žižekian Reading of the Jewish Question in The Merchant of Venice Shih - pei Kuo National Chengchi University , Taiwan [email protected] Abstract This essay borrows Zižek ’ s interpretation of racism which combines the Marxist and psychoanalytic perspectives to read Shakespeare ’ s The Merchant of Venice . I argue that Shylock , the Jewish usurer , embodies both the structural contradiction of capitalism and the social contradiction which characterizes the Venetian setting torn by capitalism and Christianity. As Shylock exposes these contradictions which the Christian Venetians refuse to confront, h e is destined to be a scapegoat. From the Marxist point of view, the survival of capitalism relies on incessant production, which also means incessant investment of capital. Therefore, an active financial system is requisite to sustain the prosperity of ca pitalism. Paradoxically, this necessary condition of capitalism which facilitates the maximum use of cash is also its inherent vulnerability: once the circulation of cash is disrupted, it can lead to the crisis of the overall domino - effect collapse. The us ury represented by Shylock indeed reflects such inherent contradiction of capitalism. Also, usury, which excludes any human factor and only engages the direct monetary exchange, also contradicts the Christian orthodox belief of generosity and unrequited de votion. These central Christian values a re certainly questioned as Bassa nio ’ s courtship of Portia, based on his disguised wealth, is indistinguishable from a profitable enterprise. From the psychoanalytic point of view, Shylock ’ s fas cination with money and revenge also mirrors the Christians ’ clandestine longing for these two forbidden enjoyments. -

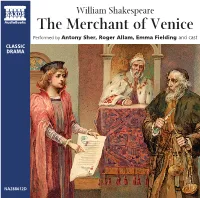

The Merchant of Venice Performed by Antony Sher, Roger Allam, Emma Fielding and Cast CLASSIC DRAMA

William Shakespeare The Merchant of Venice Performed by Antony Sher, Roger Allam, Emma Fielding and cast CLASSIC DRAMA NA288612D 1 Act 1 Scene 1: In sooth, I know not why I am so sad: 9:55 2 Act 1 Scene 2: By my troth, Nerissa, my little body is aweary… 7:20 3 Act 1 Scene 3: Three thousand ducats; well. 6:08 4 Signior Antonio, many a time and oft… 4:06 5 Act 2 Scene 1: Mislike me not for my complexion… 2:26 6 Act 2 Scene 2: Certainly my conscience… 4:21 7 Nay, indeed, if you had your eyes, you might fail of… 4:19 8 Father, in. I cannot get a service, no; 2:49 9 Act 2 Scene 3: Launcelot I am sorry thou wilt leave my father so: 1:15 10 Act 2 Scene 4: Nay, we will slink away in supper-time, 1:50 11 Act 2 Scene 5: Well Launcelot, thou shalt see, 3:16 12 Act 2 Scene 6: This is the pent-house under which Lorenzo… 1:32 13 Here, catch this casket; it is worth the pains. 1:49 14 Act 2 Scene 7: Go draw aside the curtains and discover… 5:04 15 O hell! what have we here? 1:23 16 Act 2 Scene 8: Why, man, I saw Bassanio under sail: 2:27 17 Act 2 Scene 9: Quick, quick, I pray thee; draw the curtain straight: 6:48 2 18 Act 3 Scene 1: Now, what news on the Rialto Salerino? 2:13 19 To bait fish withal: 5:17 20 Act 3 Scene 2: I pray you, tarry: pause a day or two… 4:39 21 Tell me where is fancy bred… 6:52 22 You see me, Lord Bassanio, where I stand… 9:56 23 Act 3 Scene 3: Gaoler, look to him: tell not of Mercy… 2:05 24 Act 3 Scene 4: Portia, although I speak it in your presence… 3:56 25 Act 3 Scene 5: Yes, truly; for, look you the sins of the father… 4:28 26 Act 4 Scene 1: What, is Antonio here? 4:42 27 What judgment shall I dread, doing. -

Baconian Essays

Ex Libris C. K. OGDEN THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.arcliive.org/details/baconianessaysOOsmit BACONIAN ESSAYS BACONIAN ESSAYS BY E. W. SMITHSON WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND TWO ESSAYS BY SIR GEORGE GREENWOOD LONDON CECIL PALMER OAKLEY HOUSE, 14-18 BLOOMSBURY ST., W.C. i First Edition Copy- right 1922 CONTENTS PAGE Introductory (by G. Greenwood) ... 7 Five Essays by E. W. Smithson The Masque of "Time Vindicated" . 41 Shakespeare—A Theory . .69 Ben Jonson and Shakespeare . .97 " " Bacon and Poesy . 123 " The Tempest" and Its Symbolism . 149 Two Essays by G. Greenwood The Common Knowledge of Shakespeare and Bacon 161 The Northumberland Manuscript . 187 Final Note (G. G.) . , . 223 J /',-S ^ a.^'1-^U- a BACONIAN ESSAYS INTRODUCTORY Henry James, in a letter to Miss Violet Hunt, thus delivers himself with regard to the authorship of " " — the plays and poems of Shakespeare * : " I am * a sort of ' haunted by the conviction that the divine William is the biggest and most successful fraud ever practised on a patient world. The more I turn him round and round the more he so affects me." Now I do not for a moment suppose that in so writing the late Mr. Henry James had any intention of affixing the stigma of personal fraud upon William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon. Doubtless he used the term '* fraud " in a semi-jocular vein as we so often hear it made use of in the colloquial language of the present day, and his meaning is nothing more, and nothing less, than this, viz., that the beHef that the plays and poems of " Shake- speare " were, in truth and in fact, the work of " the man from Stratford," (as he subsequently, in the same letter, styles *' the divine William ") is one of the greatest of all the many delusions which have, * Letters of Henry James. -

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory -

Usury As a Human Problem in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice

USURY AS A HUMAN PROBLEM IN SHAKESPEARE’S MERCHANT OF VENICE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Steven Petherbridge In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major Department: English Option: Literature March 2017 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title Usury as a Human Problem in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice By Steven Petherbridge The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Verena Theile Chair Miriam Mara John Cox Approved: March 21, 2017 Elizabeth Birmingham Date Department Chair ABSTRACT Shakespeare’s Shylock from the Merchant of Venice is a complex character who not only defies simple definition but also takes over a play in which he is not the titular character. How Shakespeare arrived at Shylock in the absence of a Jewish presence in early modern England, as well as what caused the playwright to humanize his villain when other playwrights had not is the subject of much debate. This thesis shows Shakespeare’s humanizing of Shylock as a blurring of the lines between Jews and Christians, and as such, a shift of usury from a uniquely Jewish problem to a human problem. This shift is then explicated in terms of a changing England in a time where economic necessity challenged religious authority and creating compassion for a Jew on the stage symbolically created compassion for Christian usurers as well. -

Shylock : a Performance History with Particular Reference to London And

University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. CHAPTER 1 SHYLOCK & PERFORMANCE Such are the controversies which potentially arise from any new production of The Merchant of Venice, that no director or actor can prepare for a fresh interpretation of the character of Shylock without an overshadowing awareness of the implications of getting it wrong. This study is an attempt to describe some of the many and various ways in which productions of The Merchant of Venice have either confronted or side-stepped the daunting theatrical challenge of presenting the most famous Jew in world literature in a play which, most especially in recent times, inescapably lives in the shadow of history. I intend in this performance history to allude to as wide a variety of Shylocks as seems relevant and this will mean paying attention to every production of the play in the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, as well as every major production in London since the time of Irving. For reasons of practicality, I have confined my study to the United Kingdom1 and make few allusions to productions which did not originate in either Stratford or London. -

Forging Italian Jewish Identities 1516 –1870

FORGING Italian JEWISH IDENTITIES 1516 – 1870 Fort Mason Center, Building C San Francisco, CA 94123 Photo by Alberto Jona Falco, Milan, Italy www.museoitaloamericano.org SEPTEMBER 25, 2008 – february 15, 2009 MUSEO ItaloAMERICANO san francisco, california FORging itALiAn JewiSH identitieS 1516 – 1870 “Italian Jews! Two great names, two enviable glories, two splendid crowns are joined together in you. Who among you, in human and divine glories, does not reverently bow before the prodigious names of Moses and Dante?” — Rabbi Elia Benamozegh, 1847 A FORewORd by David M. Rosenberg-Wohl, Curator Italy continues to capture our imagination. For How do we respond to the notion that, in this some, it is the land of our family’s culture. Others country of Western culture and in the years of us embrace the food, the language, the art, the following the Renaissance, cities of Italy increasingly civilization. We travel to Rome and see the dome of confined their Jewish population and restricted their St. Peter’s, beacon of the Catholic faith. We surround activities? What does the ghetto mean? What effect ourselves with the glories of Renaissance art and did it have? How can we understand this period of architecture in Florence and Siena. We lose ourselves history on its own terms, separate from our own in the magical canals, passageways and pigeons of time and yet profoundly affecting it? that city of islands, Venice. The ghetto was For those of us who are Jewish restrictive, but it was or interested in the relationship also progressive. It was of Judaism and Christianity, designed to separate Italy is a land of particular Jews from Christians fascination.