The Royal Entomological Society Book of British Insects Peter C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenetics, Comparative Parasitology, and Host Affinities of Chipmunk Sucking Lice and Pinworms Kayce Bell

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Biology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-1-2016 Coevolving histories inside and out: phylogenetics, comparative parasitology, and host affinities of chipmunk sucking lice and pinworms Kayce Bell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds Recommended Citation Bell, Kayce. "Coevolving histories inside and out: phylogenetics, comparative parasitology, and host affinities of chipmunk sucking lice and pinworms." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds/120 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kayce C. Bell Candidate Department of Biology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Joseph A. Cook , Chairperson Dr. John R. Demboski Dr. Irene Salinas Dr. Kenneth Whitney Dr. Jessica Light i COEVOLVING HISTORIES INSIDE AND OUT: PHYLOGENETICS, COMPARATIVE PARASITOLOGY, AND HOST AFFINITIES OF CHIPMUNK SUCKING LICE AND PINWORMS by KAYCE C. BELL B.S., Biology, Idaho State University, 2003 M.S., Biology, Idaho State University, 2006 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Biology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July 2016 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completion of my degree and this dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and support of my mentors, family, and friends. Dr. Joseph Cook first introduced me to phylogeography and parasites as undergraduate and has proven time and again to be the best advisor a graduate student could ask for. -

Monitoring and Sampling Manual 2018

Monitoring and Sampling Manual Environmental Protection (Water) Policy 2009 Prepared by: Water Quality and Investigation, Department of Environment and Science (DES) © State of Queensland, 2018. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5470. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. large print or audiotape) on request for people with vision impairment; phone +61 7 3170 5470 or email <[email protected]>. Citation DES. 2018. Monitoring and Sampling Manual: Environmental Protection (Water) Policy. Brisbane: Department of Environment and Science Government. Acknowledgements The revision and update of this manual was led by Dr Suzanne Vardy, with the valued assistance of Dr Phillipa Uwins, Leigh Anderson and Brenda Baddiley. Thanks are given to many experts who reviewed and contributed to the documents relating to their field of expertise. This includes government staff from within the Department of Environment and Science, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy and many from outside government. -

Florida Entomologist Published by the Florida Entomological Society Volume 99, Number 3 — September 2016

Florida Entomologist Published by the Florida Entomological Society Volume 99, Number 3 — September 2016 Research Papers Romo-Asunción, Diana, Marco Antonio Ávila-Calderón, Miguel Angel Ramos-López, Juan Esteban Barranco-Florido, Silvia Rodríguez-Navarro, Sergio Romero-Gomez, Eugenia Josefina Aldeco-Pérez, Juan Ramiro Pacheco-Aguilar, and Miguel Angel Rico-Rodríguez—Juvenomimetic and insecticidal activitiesSenecio of salignus (Asteraceae) and Salvia microphylla (Lamiaceae) on Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) . 345-351 Barroso-Aké, Hanzel J., Juan Cibrián-Tovar, Obdulia L. Segura-León, and Ausencio Azuara-Domínguez—Pre-courtship behavior and the effect of age on its duration in Diatraea magnifactella (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) . 352-354 Sisson, Melissa S., Carlos A. Santamaria, Autumn J. Smith-Herron, Tamara J. Cook, and Jerry L. Cook—Geographical color pattern of Argia apicalis (Odonata: Coenagrionidae) in the absence of molecular variation . 355-362 Tillman, P. Glynn and Ted E. Cottrell—Stink bugs (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in pheromone-baited traps near crop field edges in Georgia, USA . 363-370 Song, YueHua, ZiZhong Li, and RenHuai Dai—A remarkable new genus and species of Erythroneurini (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae: Typhlocybinae) from China . 371-375 Hernández-Baz, Fernando, Helena Romo, Jorge M. González, María de Jesús Martínez Hernández, and Roberto Gámez Pastrana—Maximum entropy niche-based modeling (Maxent) of potential geographical distribution of Coreura albicosta (Lepidoptera: Erebidae: Ctenuchina) in Mexico . 376-380 Bortoli, Lígia Caroline, Ruben Machota Jr., Flávio Roberto Mello Garcia, and Marcos Botton—Evaluation of food lures for fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) captured in a citrus orchard of the Serra Gaúcha . 381-384 Zheng, Min-Lin, Cornelis van Achterberg, and Jia-Hua Chen—A new species of the genus Proantrusa Tobias (Hymenoptera: Braconidae: Alysiinae) from northwestern China . -

Field Release of the Insects Calophya Latiforceps

United States Department of Field Release of the Insects Agriculture Calophya latiforceps Marketing and Regulatory (Hemiptera: Calophyidae) and Programs Pseudophilothrips ichini Animal and Plant Health Inspection (Thysanoptera: Service Phlaeothripidae) for Classical Biological Control of Brazilian Peppertree in the Contiguous United States Environmental Assessment, May 2019 Field Release of the Insects Calophya latiforceps (Hemiptera: Calophyidae) and Pseudophilothrips ichini (Thysanoptera: Phlaeothripidae) for Classical Biological Control of Brazilian Peppertree in the Contiguous United States Environmental Assessment, May 2019 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. Additional information can be found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_file.html. -

BÖCEKLERİN SINIFLANDIRILMASI (Takım Düzeyinde)

BÖCEKLERİN SINIFLANDIRILMASI (TAKIM DÜZEYİNDE) GÖKHAN AYDIN 2016 Editör : Gökhan AYDIN Dizgi : Ziya ÖNCÜ ISBN : 978-605-87432-3-6 Böceklerin Sınıflandırılması isimli eğitim amaçlı hazırlanan bilgisayar programı için lütfen aşağıda verilen linki tıklayarak programı ücretsiz olarak bilgisayarınıza yükleyin. http://atabeymyo.sdu.edu.tr/assets/uploads/sites/76/files/siniflama-05102016.exe Eğitim Amaçlı Bilgisayar Programı ISBN: 978-605-87432-2-9 İçindekiler İçindekiler i Önsöz vi 1. Protura - Coneheads 1 1.1 Özellikleri 1 1.2 Ekonomik Önemi 2 1.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 2 2. Collembola - Springtails 3 2.1 Özellikleri 3 2.2 Ekonomik Önemi 4 2.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 4 3. Thysanura - Silverfish 6 3.1 Özellikleri 6 3.2 Ekonomik Önemi 7 3.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 7 4. Microcoryphia - Bristletails 8 4.1 Özellikleri 8 4.2 Ekonomik Önemi 9 5. Diplura 10 5.1 Özellikleri 10 5.2 Ekonomik Önemi 10 5.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 11 6. Plocoptera – Stoneflies 12 6.1 Özellikleri 12 6.2 Ekonomik Önemi 12 6.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 13 7. Embioptera - webspinners 14 7.1 Özellikleri 15 7.2 Ekonomik Önemi 15 7.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 15 8. Orthoptera–Grasshoppers, Crickets 16 8.1 Özellikleri 16 8.2 Ekonomik Önemi 16 8.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 17 i 9. Phasmida - Walkingsticks 20 9.1 Özellikleri 20 9.2 Ekonomik Önemi 21 9.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 21 10. Dermaptera - Earwigs 23 10.1 Özellikleri 23 10.2 Ekonomik Önemi 24 10.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 24 11. Zoraptera 25 11.1 Özellikleri 25 11.2 Ekonomik Önemi 25 11.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 26 12. -

Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: an Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C

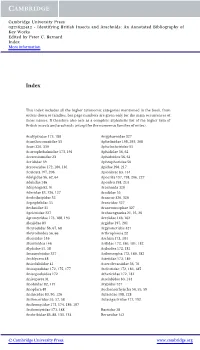

Cambridge University Press 0521632412 - Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: An Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C. Barnard Index More information Index This index includes all the higher taxonomic categories mentioned in the book, from orders down to families, but page numbers are given only for the main occurrences of those names. It therefore also acts as a complete alphabetic list of the higher taxa of British insects and arachnids (except for the numerous families of mites). Acalyptratae 173, 188 Anyphaenidae 327 Acanthosomatidae 55 Aphelinidae 198, 293, 308 Acari 320, 330 Aphelocheiridae 55 Acartophthalmidae 173, 191 Aphididae 56, 62 Acerentomidae 23 Aphidoidea 56, 61 Acrididae 39 Aphrophoridae 56 Acroceridae 172, 180, 181 Apidae 198, 217 Aculeata 197, 206 Apioninae 83, 134 Adelgidae 56, 62, 64 Apocrita 197, 198, 206, 227 Adelidae 146 Apoidea 198, 214 Adephaga 82, 91 Arachnida 320 Aderidae 83, 126, 127 Aradidae 55 Aeolothripidae 52 Araneae 320, 326 Aepophilidae 55 Araneidae 327 Aeshnidae 31 Araneomorphae 327 Agelenidae 327 Archaeognatha 21, 25, 26 Agromyzidae 173, 188, 193 Arctiidae 146, 162 Alexiidae 83 Argidae 197, 201 Aleyrodidae 56, 67, 68 Argyronetidae 327 Aleyrodoidea 56, 66 Arthropleona 22 Alucitidae 146 Aschiza 173, 184 Alucitoidea 146 Asilidae 172, 180, 181, 182 Alydidae 55, 58 Asiloidea 172, 181 Amaurobiidae 327 Asilomorpha 172, 180, 182 Amblycera 48 Asteiidae 173, 189 Anisolabiidae 41 Asterolecaniidae 56, 70 Anisopodidae 172, 175, 177 Atelestidae 172, 183, 185 Anisopodoidea 172 Athericidae 172, 181 Anisoptera 31 Attelabidae 83, 134 Anobiidae 82, 119 Atypidae 327 Anoplura 48 Auchenorrhyncha 54, 55, 59 Anthicidae 83, 90, 126 Aulacidae 198, 228 Anthocoridae 55, 57, 58 Aulacigastridae 173, 192 Anthomyiidae 173, 174, 186, 187 Anthomyzidae 173, 188 Baetidae 28 Anthribidae 83, 88, 133, 134 Beraeidae 142 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521632412 - Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: An Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C. -

Hastings Slide Collection3

HASTINGS NATURAL HISTORY RESERVATION SLIDE COLLECTION 1 ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES SUBSPECIES AUTHOR DATE # SLIDES COMMENTS/CORRECTIONS Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Diamanus montanus Baker 1895 221 currently Oropsylla (Diamanus) montana Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Diamanus spp. 1 currently Oropsylla (Diamanus) spp. Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Foxella ignota acuta Stewart 1940 402 syn. of F. ignota franciscana (Roths.) Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Foxella ignota (Baker) 1895 2 Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Foxella spp. 15 Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Malaraeus spp. 1 Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Malaraeus telchinum Rothschild 1905 491 M. telchinus Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Monopsyllus fornacis Jordan 1937 57 currently Eumolpianus fornacis Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Monopsyllus wagneri (Baker) 1904 131 currently Aetheca wagneri Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Monopsyllus wagneri ophidius Jordan 1929 2 syn. of Aetheca wagneri Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Opisodasys nesiotus Augustson 1941 2 Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Orchopeas sexdentatus (Baker) 1904 134 Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Orchopeas sexdentatus nevadensis (Jordan) 1929 15 syn. of Orchopeas agilis (Baker) Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Orchopeas spp. 8 Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Orchopeas latens (Jordan) 1925 2 Siphonaptera Ceratophyllidae Orchopeas leucopus (Baker) 1904 2 Siphonaptera Ctenophthalmidae Anomiopsyllus falsicalifornicus C. Fox 1919 3 Siphonaptera Ctenophthalmidae Anomiopsyllus congruens Stewart 1940 96 incl. 38 Paratypes; syn. of A. falsicalifornicus Siphonaptera -

Insecta: Psocodea: 'Psocoptera'

Molecular systematics of the suborder Trogiomorpha (Insecta: Title Psocodea: 'Psocoptera') Author(s) Yoshizawa, Kazunori; Lienhard, Charles; Johnson, Kevin P. Citation Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 146(2): 287-299 Issue Date 2006-02 DOI Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/43134 The definitive version is available at www.blackwell- Right synergy.com Type article (author version) Additional Information File Information 2006zjls-1.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKZOJZoological Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4082The Lin- nean Society of London, 2006? 2006 146? •••• zoj_207.fm Original Article MOLECULAR SYSTEMATICS OF THE SUBORDER TROGIOMORPHA K. YOSHIZAWA ET AL. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2006, 146, ••–••. With 3 figures Molecular systematics of the suborder Trogiomorpha (Insecta: Psocodea: ‘Psocoptera’) KAZUNORI YOSHIZAWA1*, CHARLES LIENHARD2 and KEVIN P. JOHNSON3 1Systematic Entomology, Graduate School of Agriculture, Hokkaido University, Sapporo 060-8589, Japan 2Natural History Museum, c.p. 6434, CH-1211, Geneva 6, Switzerland 3Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 East Peabody Drive, Champaign, IL 61820, USA Received March 2005; accepted for publication July 2005 Phylogenetic relationships among extant families in the suborder Trogiomorpha (Insecta: Psocodea: ‘Psocoptera’) 1 were inferred from partial sequences of the nuclear 18S rRNA and Histone 3 and mitochondrial 16S rRNA genes. Analyses of these data produced trees that largely supported the traditional classification; however, monophyly of the infraorder Psocathropetae (= Psyllipsocidae + Prionoglarididae) was not recovered. Instead, the family Psyllipso- cidae was recovered as the sister taxon to the infraorder Atropetae (= Lepidopsocidae + Trogiidae + Psoquillidae), and the Prionoglarididae was recovered as sister to all other families in the suborder. -

About the Book the Format Acknowledgments

About the Book For more than ten years I have been working on a book on bryophyte ecology and was joined by Heinjo During, who has been very helpful in critiquing multiple versions of the chapters. But as the book progressed, the field of bryophyte ecology progressed faster. No chapter ever seemed to stay finished, hence the decision to publish online. Furthermore, rather than being a textbook, it is evolving into an encyclopedia that would be at least three volumes. Having reached the age when I could retire whenever I wanted to, I no longer needed be so concerned with the publish or perish paradigm. In keeping with the sharing nature of bryologists, and the need to educate the non-bryologists about the nature and role of bryophytes in the ecosystem, it seemed my personal goals could best be accomplished by publishing online. This has several advantages for me. I can choose the format I want, I can include lots of color images, and I can post chapters or parts of chapters as I complete them and update later if I find it important. Throughout the book I have posed questions. I have even attempt to offer hypotheses for many of these. It is my hope that these questions and hypotheses will inspire students of all ages to attempt to answer these. Some are simple and could even be done by elementary school children. Others are suitable for undergraduate projects. And some will take lifelong work or a large team of researchers around the world. Have fun with them! The Format The decision to publish Bryophyte Ecology as an ebook occurred after I had a publisher, and I am sure I have not thought of all the complexities of publishing as I complete things, rather than in the order of the planned organization. -

Psocoptera Em Cavernas Do Brasil: Riqueza, Composição E Distribuição

PSOCOPTERA EM CAVERNAS DO BRASIL: RIQUEZA, COMPOSIÇÃO E DISTRIBUIÇÃO THAÍS OLIVEIRA DO CARMO 2009 THAÍS OLIVEIRA DO CARMO PSOCOPTERA EM CAVERNAS DO BRASIL: RIQUEZA, COMPOSIÇÃO E DISTRIBUIÇÃO Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Federal de Lavras, como parte das exigências do programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia Aplicada, área de concentração em Ecologia e Conservação de Paisagens Fragmentadas e Agroecossistemas, para obtenção do título de “Mestre”. Orientador Prof. Dr. Rodrigo Lopes Ferreira LAVRAS MINAS GERAIS – BRASIL 2009 Ficha Catalográfica Preparada pela Divisão de Processos Técnicos da Biblioteca Central da UFLA Carmo, Thaís Oliveira do. Psocoptera em cavernas do Brasil: riqueza, composição e distribuição / Thaís Oliveira do Carmo. – Lavras : UFLA, 2009. 98 p. : il. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Lavras, 2009. Orientador: Rodrigo Lopes Ferreira. Bibliografia. 1. Insetos cavernícolas. 2. Ecologia. 3. Diversidade. 4. Fauna cavernícola. I. Universidade Federal de Lavras. II. Título. CDD – 574.5264 THAÍS OLIVEIRA DO CARMO PSOCOPTERA EM CAVERNAS DO BRASIL: RIQUEZA, COMPOSIÇÃO E DISTRIBUIÇÃO Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Federal de Lavras, como parte das exigências do programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia Aplicada, área de concentração em Ecologia e Conservação de Paisagens Fragmentadas e Agroecossistemas, para obtenção do título de “Mestre”. APROVADA em 04 de dezembro de 2009 Prof. Dr. Marconi Souza Silva UNILAVRAS Prof. Dr. Luís Cláudio Paterno Silveira UFLA Prof. Dr. Rodrigo Lopes Ferreira UFLA (Orientador) LAVRAS MINAS GERAIS – BRASIL ...Então não vá embora Agora que eu posso dizer Eu já era o que sou agora Mas agora gosto de ser (Poema Quebrado - Oswaldo Montenegro) AGRADECIMENTOS A Deus, pois com Ele nada nessa vida é impossível! Agradeço aos meus pais, Joaquim e Madalena, pela oportunidade e apoio. -

A New Genus in the Family Ptiloneuridae (Psocodea: 'Psocoptera': Psocomorpha: Epipsocetae) from Brazil

Zootaxa 3914 (2): 168–174 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3914.2.6 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CE5BA8ED-5210-42FF-BA15-F2B372364BD6 A new genus in the family Ptiloneuridae (Psocodea: ‘Psocoptera’: Psocomorpha: Epipsocetae) from Brazil ALBERTO MOREIRA DA SILVA NETO1 & ALFONSO N. GARCÍA ALDRETE2 1Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia—INPA, CPEN—Programa de Pós-Graduação em Entomologia, Campus II, Caixa postal 478, CEP 69011-97, Manaus, Amazonas, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] 2Departamento de Zoología, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Apartado Postal 70-153, 04510 Méxi- co, D. F., MÉXICO. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new ptiloneurid genus from Brazil, Brasineura n. gen., is described and illustrated. It includes two species, both known only from males, one from the Chapada Diamantina (State of Bahia), and one troglophilic species from the State of Pará. It differs from all other known ptiloneurid genera, in which the males are known, by the unique structure of the phallo- some, and by having a uniquely shaped hypandrium of a single sclerite. An updated identification key to the genera of Ptiloneuridae is presented and the synonymy between Brisacia and Loneura is proposed. Key words: taxonomy, Neotropics, Epipsocetae Introduction Ptiloneuridae is one of the families in the psocomorphan infraorder Epipsocetae (Yoshizawa 2002). It presently includes the genera Belicania García Aldrete, Euplocania Enderlein, Omilneura García Aldrete, Perucania New & Thornton, Timnewia García Aldrete, Triplocania Roesler, Willreevesia García Aldrete, all with the hindwing vein M unbranched, and Loneura Navás, Loneuroides García Aldrete, Ptiloneura Enderlein, and Ptiloneuropsis Roesler, these last four genera with hindwing vein M having from 2 to 5 branches. -

Insecta Diptera) in Freshwater (Excluding Simulidae, Culicidae, Chironomidae, Tipulidae and Tabanidae) Rüdiger Wagner University of Kassel

Entomology Publications Entomology 2008 Global diversity of dipteran families (Insecta Diptera) in freshwater (excluding Simulidae, Culicidae, Chironomidae, Tipulidae and Tabanidae) Rüdiger Wagner University of Kassel Miroslav Barták Czech University of Agriculture Art Borkent Salmon Arm Gregory W. Courtney Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ent_pubs BoudewPart ofijn the GoBddeeiodivrisersity Commons, Biology Commons, Entomology Commons, and the TRoyerarle Bestrlgiialan a Indnstit Aquaute of Nticat uErcaol Scienlogyce Cs ommons TheSee nex tompc page forle addte bitioniblaiol agruthorapshic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ ent_pubs/41. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Entomology Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Global diversity of dipteran families (Insecta Diptera) in freshwater (excluding Simulidae, Culicidae, Chironomidae, Tipulidae and Tabanidae) Abstract Today’s knowledge of worldwide species diversity of 19 families of aquatic Diptera in Continental Waters is presented. Nevertheless, we have to face for certain in most groups a restricted knowledge about distribution, ecology and systematic,