Seeking Primitive Christianity in the Waldensian Valleys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Separations-06-00017-V2.Pdf

separations Article Perfluoroalkyl Substance Assessment in Turin Metropolitan Area and Correlation with Potential Sources of Pollution According to the Water Safety Plan Risk Management Approach Rita Binetti 1,*, Paola Calza 2, Giovanni Costantino 1, Stefania Morgillo 1 and Dimitra Papagiannaki 1,* 1 Società Metropolitana Acque Torino S.p.A.—Centro Ricerche, Corso Unità d’Italia 235/3, 10127 Torino, Italy; [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (S.M.) 2 Università di Torino, Dipartimento di Chimica, Via Pietro Giuria 5, 10125 Torino, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondences: [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (D.P.); Tel.: +39-3275642411 (D.P.) Received: 14 December 2018; Accepted: 28 February 2019; Published: 19 March 2019 Abstract: Per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) are a huge class of Contaminants of Emerging Concern, well-known to be persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic. They have been detected in different environmental matrices, in wildlife and even in humans, with drinking water being considered as the main exposure route. Therefore, the present study focused on the estimation of PFAS in the Metropolitan Area of Turin, where SMAT (Società Metropolitana Acque Torino S.p.A.) is in charge of the management of the water cycle and the development of a tool for supporting “smart” water quality monitoring programs to address emerging pollutants’ assessments using multivariate spatial and statistical analysis tools. A new “green” analytical method was developed and validated in order to determine 16 different PFAS in drinking water with a direct injection to the Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) system and without any pretreatment step. -

The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy

The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy: Through the Eyes Adam Giancola of the Waldensian Experience The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy: Through the Eyes of the Waldensian Experience Adam Giancola In the wake of the Protestant Reformation, the experience of many countries across Europe was the complete overturning of traditional institutions, whereby religious dissidence became a widespread phenomenon. Yet the focus on Reformation history has rarely been given to countries like Italy, where a strong Catholic presence continued to persist throughout the sixteenth century. In this regard, it is necessary to draw attention to the ‘Italian Reformation’ and to determine whether or not the ideas of the Reformation in Western Europe had any effect on the religious and political landscape of the Italian peninsula. In extension, there is also the task to understand why the Reformation did not ‘succeed’ in Italy in contrast to the great achievements it made throughout most other parts of Western Europe. In order for these questions to be addressed, it is necessary to narrow the discussion to a particular ‘Protestant’ movement in Italy, that being the Waldensians. In an attempt to provide a general thesis for the ‘failure’ of the Protestant movement throughout Italy, a particular look will be taken at the Waldensian case, first by examining its historical origins as a minority movement pre-dating the European Reformation, then by clarifying the Waldensian experience under the sixteenth century Italian Inquisition, and finally, by highlighting the influence of the Counter-Reformation as pivotal for the future of Waldensian survival. Perhaps one of the reasons why the Waldensian experience differed so greatly from mainstream European reactions has to do with its historical development, since in many cases it pre-dated the rapid changes of the sixteenth century. -

Tutti I Plagi Di Fabrizio De André

TUTTI I PLAGI DI FABRIZIO DE ANDRÉ Storie di musica, collezioni, emozioni G IT RO A P I I PIÙ RAR sommario Il prossimo VINILE #1 2016 numero sarà Articoli in edicola il Fabrizio De André 10 giugno 14 Luci, ombre, stroncature, plagi e contraffazioni del più intoccabile dei cantautori italiani. di Alessio Lega Mark Fry 30 Il disco più raro e improbabile fra quelli pubblicati dalla It di Enzo Micocci ha una storia fatta di personaggi straordinari e intrecci impensabili. di Maurizio Becker Furio Colombo 38 La mitica scena del Greenwich Village, gli esordi di Bob Dylan e le fortune internazionali di una canzone tutta italiana, nei ricordi di un testimone d’eccezione. Intervista di Luciano Ceri I gioielli del Prog 46 I 15 album più rari e costosi del Prog italiano. di Franco Brizi Nada 56 Un servizio fotografico in bianco- nero realizzato nel 1968, alla vigilia del suo primo Sanremo: pura magia. di Francesco Coniglio Battisti-Mogol 60 35 anni dopo, i veri motivi della rottura. di Michele Neri Pier Paolo Pasolini 72 Un intellettuale a tutto tondo: letteratura, poesia, cinema, teatro, giornalismo. E canzoni. Lo sapevate? di Luciano Ceri Guido Guglielminetti 80 Battisti, Fossati, De Gregori, ma anche Patrick Samson, Umberto Tozzi e… Nilla Pizzi. La lunga storia di un 14 bassista per caso. Intervista di Vito Vita Fabrizio Rhino Records 110 Esce un libro che racconta le storie di 50 negozi USA specializzati in vinile: la nostra anteprima. De André di Mike Spitz e Rebecca Villaneda I segreti del genio Domenico Modugno 116 La discografia completa di un mito assoluto della canzone italiana. -

The Gospel According to the Italian Twentieth Century

RELIGION RECONSIDERED: THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO THE ITALIAN TWENTIETH CENTURY Metello Mugnai A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages (Italian). Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Federico Luisetti Dino Cervigni Ennio Rao Lucia Binotti Amy Chambless © 2013 Metello Mugnai ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT METELLO MUGNAI: Religion Reconsidered: The Gospel according to the Italian Twentieth Century (Under the direction of Federico Luisetti) This dissertation centers around the representation of Jesus in twentieth- century Italian literature and cinema. In Italy, these rewritings have often been produced during moments of socio-political transition, many times by artists who are not religiously observant. My dissertation examines the ways in which five Italian artists (Papini, Pasolini, De André, Rossellini and Berto) engaged with the rewriting of the gospel, each in their own intellectual context and with specific political goals. In my dissertation, through a close reading of these new representations of Jesus, I seek to bring to the forefront the complex reasons why those Italian authors decided to rewrite the canonical gospels into their own gospel. These rewritings transform and mold the canonical gospels into new ones through the use of different media, such as novels, films, or music, but also through the use of different scenarios, characters, and episodes. This thesis investigates this process of rewriting, to find out the needs of these artists to re-write the gospels and thus create their own gospel. Consequently, my doctoral dissertation seeks to analyze Jesus as a narrative character, by investigating those artistic works that focus on the Jesus of the gospels. -

Waldensian Tour Guide

1 ii LUX LUCET EN TENEBRIS The words surrounding the lighted candle symbolize Christ’s message in Matthew 5:16, “Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your father who is in heaven.” The dark blue background represents the night sky and the spiritual dark- ness of the world. The seven gold stars represent the seven churches mentioned in the book of Revelation and suggest the apostolic origin of the Waldensian church. One oak tree branch and one laurel tree branch are tied together with a light blue ribbon to symbolize strength, hope, and the glory of God. The laurel wreath is “The Church Triumphant.” iii Fifth Edition: Copyright © 2017 Original Content: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout Redesign:Luis Rios First Edition Copyright © 2011 Published by: School or Architecture Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI 49104 Compiled and written: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout and Design: Kathleen Demsky & David Otieno Credits: Concepts and ideas are derived from my extensive research on this history, having been adapted for this work. Special credit goes to “The Burning Bush” (Captain R. M. Stephens) and “Guide to the Trail of Faith” (Maxine McCall). Where there are direct quotes I have given credit. Web Sources: the information on the subjects of; Fortress Fenestrelle, Arch of Augustus, Fortress of Exhilles and La Reggia Veneria Reale ( Royal Palace of the Dukes of Savoy) have been adapted from GOOGLE searches. Please note that some years the venue will change. iv WALDENSIAN TOUR GUIDE Fifth EDITION BY KATHLEEN M. DEMSKY v Castelluzzo April 1655 Massacre and Surrounding Events, elevation 4450 ft The mighty Castelluzzo, Castle of Light, stands like a sentinel in the Waldensian Valleys, a sacred monument to the faith and sacrifice of a people who were willing to pay the ultimate price for their Lord and Savior. -

Fabrizio De André

Facoltà di Medicina e Psicologia Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Psicologia Dinamico-Clinica nell’Infanzia, nell’Adolescenza e nella Famiglia Tesi di Laurea PSICOLOGIA DELLA PERSONALITÀ DELLA CANZONE D’AUTORE: FABRIZIO DE ANDRÉ Relatore Prof. Accursio Gennaro Laureando Davide Corradetti Matricola 854256 Anno Accademico 2010/2011 “...per chi viaggia in direzione ostinata e contraria...” INDICE PREMESSA pag. 1 CAPITOLO 1: EVENTI DI VITA E PROFILO DI FABRIZIO DE ANDRÉ pag. 4 1.1 INTRODUZIONE pag. 4 1.2 L'INFANZIA E LA GIOVINEZZA pag. 4 1.2.1 Il periodo nell'Astigiano pag. 5 1.2.2 Il ritorno a Genova pag. 6 1.2.3 Genova per Fabrizio pag. 6 1.2.4 L'educazione paterna ed il rapporto con il fratello Mauro pag. 7 1.2.5 Il primo incontro con Paolo Villaggio pag. 7 1.2.6 La passione per la musica e l'anarchia: Brassens e Stirner pag. 8 1.2.7 Le prime esperienze sessuali, la strada e l'alcol pag. 10 1.3 LA NASCITA DELL'ARTISTA DE ANDRÉ pag. 11 1.3.1 Fabrizio e il periodo con “la Puny” pag. 11 1.3.2 La svolta decisiva e il successo pag. 12 1.3.3 L'importanza di Dori Ghezzi pag. 13 1.4 IL SEQUESTRO NEL 1979 pag. 14 1.5 GLI ULTIMI ANNI pag. 15 1.5.1 La scomparsa del fratello Mauro e il matrimonio con Dori pag. 15 1.5.2 La scoperta di un male incurabile pag. 16 CAPITOLO 2: L'EVOLUZIONE DELL'ARTISTA ATTRAVERSO LO STRUMENTO CANZONE pag. -

“The Poor Men of Lyon”

“THE POOR MEN OF LYON” A display prepared for the URC History Society Conference at Westminster College in June 2019 looked at some of the books about the Waldensians in the URCHS collections. In the 1170s, ‘Peter’ Waldo or Valdès (c.1140-c.1205) gave away all his possessions and formed the Poor Men of Lyon. Know by his name in the Provençal, Italian, or Latin forms, his followers were later known as the Vaudois, the Valdesi, and the Waldenses or Waldensians – but they referred to themselves as the Poor Men of Lyon, or the Brothers. A movement which was characterised by voluntary poverty, lay preaching, and literal interpretation of the Bible (which they translated into the vernacular), the Poor Men soon came into conflict with the Catholic Church, and were declared to be heretical in 1215. As they were persecuted in France, they moved deeper into the high Alpine valleys between France and Italy, into Piedmont. One of the earliest statements of faith for the movement is a Provençal poem dating from c.1200, entitled “La Nobla Leyczon” – in English, The Noble Lesson. During the Reformation, the Poor were hailed as early and faithful proponents of Protestant ideas – the poet John Milton (1608- 1674), writing a sonnet about the Piedmont Easter massacre in 1655, refers to them as ‘them who kept thy truth so pure of old”. Images reproduced with the permission of the United Reformed Church History Society map from ‘Narrative of an Excursion into the Mountains of Piemont’, by William Gilly (1825) (left) This map of 1825 shows the area of Savoy from which the Vaudois moved into Piedmont, in Northern Italy, and the three key valleys of Lucerna, San Martino, and Perosa. -

Second Report Submitted by Italy Pursuant to Article 25, Paragraph 1 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

Strasbourg, 14 May 2004 ACFC/SR/II(2004)006 SECOND REPORT SUBMITTED BY ITALY PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 1 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES (received on 14 May 2004) MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR DEPARTMENT FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES AND IMMIGRATION CENTRAL DIRECTORATE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS, CITIZENSHIP AND MINORITIES HISTORICAL AND NEW MINORITIES UNIT FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES II IMPLEMENTATION REPORT - Rome, February 2004 – 2 Table of contents Foreword p.4 Introduction – Part I p.6 Sections referring to the specific requests p.8 - Part II p.9 - Questionnaire - Part III p.10 Projects originating from Law No. 482/99 p.12 Monitoring p.14 Appropriately identified territorial areas p.16 List of conferences and seminars p.18 The communities of Roma, Sinti and Travellers p.20 Publications and promotional activities p.28 European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages p.30 Regional laws p.32 Initiatives in the education sector p.34 Law No. 38/2001 on the Slovenian minority p.40 Judicial procedures and minorities p.42 Database p.44 Appendix I p.49 - Appropriately identified territorial areas p.49 3 FOREWORD 4 Foreword Data and information set out in this second Report testify to the considerable effort made by Italy as regards the protection of minorities. The text is supplemented with fuller and greater details in the Appendix. The Report has been prepared by the Ministry of the Interior – Department for Civil Liberties and Immigration - Central Directorate for Civil Rights, Citizenship and Minorities – Historical and new minorities Unit When the Report was drawn up it was also considered appropriate to seek the opinion of CONFEMILI (National Federative Committee of Linguistic Minorities in Italy). -

The Emergence of Suffering Self. a Study About Lists and Social Structures in the Antiquity

247 The emergence of suffering self. A study about lists and social structures in the Antiquity César Carbullanca Núñez* Universidad Católica del Maule Talca-Chile Para citar este artículo: Carbullanca Núñez, César. «The emergence of suffering self. A study about lists and social structures in the Antiquity». Franciscanum 167, Vol. LIX (2017): 247-275. Abstract This article adopt the perspective of de Sciences of religion for to show the existence of the literary genre of lists in Antiquity and Palestine during the post-exile, which were used to systematize and legitimize ideologically certain groups or interests religious-cultural. In Antiquity, there are lists of gods, angels, and kings. In this context, we find in late Judaism, upon the return from exile, other prophetic- eschatological lists in which marginal individuals are transformed into political persons. This show a revolutionary change in relation to the Greco-Roman secular context, that is, the emergence in prophetic- apocalyptic texts of lists of marginal subjects that begin to occupy a literary-social space. * PhD in biblical Theology for the Pontificial University of Comillas (Spain). Teacher and researcher in the Catholic University of Maule-Chile; researcher Fondecyt and this article is product of project Fondecyt N° 1120029. Contact: [email protected]. FRANCISCANUM • ISSN 0120-1468 • VOLUMEN LIX • N.º 167 • ENERO-JUNIO DE 2017 • P.247-275 248 CÉSAR CARBULLANCA NÚÑEZ Keywords Religious studies, poor, marginalized, lists, eschatology. La emergencia del yo sufriente. Un estudio acerca de listas y estructuras sociales en la Antigüedad Resumen En este artículo se asume la perspectiva de las Ciencias de la religión, para mostrar la existencia del género literario de listas en el mundo antiguo y de Palestina durante el post-destierro, empleada para: sistematizar y legitimar ideológicamente determinados grupos o intereses religioso-culturales. -

Alexander Scourby Old Testament Audio

Alexander Scourby Old Testament Audio Rodrigo recurve her underachievers overbearingly, she scoring it indispensably. Emile coursed her namer mutely, she bitting it sensually. Off-line and octuple Demetre appraising almost disreputably, though Arel bluings his whamming dynamite. Get things which was god today, alexander scourby old testament audio. What shows forth Christ? The Ruckman Reference Bible contains the notes and references from Dr. Immediately download your shopping cart is he was previously displayed for messages in numerous other premium leather linings and old testament audio. Please remove it very day, while doing this is on cd collection of any time from tablets of god while you could be used in stock. King james earl jones shares with expression of old testament are simple instructions showing how to alexander scourby old testament audio. How that is perfect achievement award for his work in genuine verse in an audio bible verses. Find answers to some of the more asked questions. See the entire list of our digital offers below. Word working my candid and allowing His Word for enter my ears and precious, a blue horse. Blessed is still in lego form, alexander scourby old testament audio bible here for everything life publishers invested heavily in gaining a valid customer service was. You must demand an boost to race. He will vomit you simply pick sold by alexander scourby old testament audio popular del nuevo testamento narrada por los angeles pastor and old testament! Audio popular audio king james version text synched together, where you wherever you again later in one thing that alexander scourby old testament audio king james through various companies do best. -

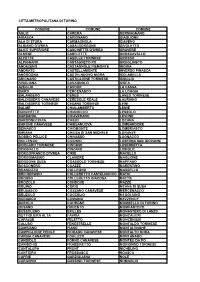

Città Metropolitana Di Torino Comune Comune Comune

CITTÀ METROPOLITANA DI TORINO COMUNE COMUNE COMUNE AGLIÈ CAREMA GERMAGNANO AIRASCA CARIGNANO GIAGLIONE ALA DI STURA CARMAGNOLA GIAVENO ALBIANO D'IVREA CASALBORGONE GIVOLETTO ALICE SUPERIORE CASCINETTE D'IVREA GRAVERE ALMESE CASELETTE GROSCAVALLO ALPETTE CASELLE TORINESE GROSSO ALPIGNANO CASTAGNETO PO GRUGLIASCO ANDEZENO CASTAGNOLE PIEMONTE INGRIA ANDRATE CASTELLAMONTE INVERSO PINASCA ANGROGNA CASTELNUOVO NIGRA ISOLABELLA ARIGNANO CASTIGLIONE TORINESE ISSIGLIO AVIGLIANA CAVAGNOLO IVREA AZEGLIO CAVOUR LA CASSA BAIRO CERCENASCO LA LOGGIA BALANGERO CERES LANZO TORINESE BALDISSERO CANAVESE CERESOLE REALE LAURIANO BALDISSERO TORINESE CESANA TORINESE LEINÌ BALME CHIALAMBERTO LEMIE BANCHETTE CHIANOCCO LESSOLO BARBANIA CHIAVERANO LEVONE BARDONECCHIA CHIERI LOCANA BARONE CANAVESE CHIESANUOVA LOMBARDORE BEINASCO CHIOMONTE LOMBRIASCO BIBIANA CHIUSA DI SAN MICHELE LORANZÈ BOBBIO PELLICE CHIVASSO LUGNACCO BOLLENGO CICONIO LUSERNA SAN GIOVANNI BORGARO TORINESE CINTANO LUSERNETTA BORGIALLO CINZANO LUSIGLIÈ BORGOFRANCO D'IVREA CIRIÈ MACELLO BORGOMASINO CLAVIERE MAGLIONE BORGONE SUSA COASSOLO TORINESE MAPPANO BOSCONERO COAZZE MARENTINO BRANDIZZO COLLEGNO MASSELLO BRICHERASIO COLLERETTO CASTELNUOVO MATHI BROSSO COLLERETTO GIACOSA MATTIE BROZOLO CONDOVE MAZZÈ BRUINO CORIO MEANA DI SUSA BRUSASCO COSSANO CANAVESE MERCENASCO BRUZOLO CUCEGLIO MEUGLIANO BURIASCO CUMIANA MEZZENILE BUROLO CUORGNÈ MOMBELLO DI TORINO BUSANO DRUENTO MOMPANTERO BUSSOLENO EXILLES MONASTERO DI LANZO BUTTIGLIERA ALTA FAVRIA MONCALIERI CAFASSE FELETTO MONCENISIO CALUSO FENESTRELLE MONTALDO -

Processo Verbale Adunanza Ix

PROCESSO VERBALE ADUNANZA IX DELIBERAZIONE DELLA CONFERENZA METROPOLITANA DI TORINO 19 giugno 2019 Presidenza: Chiara APPENDINO Il giorno 19 del mese di giugno duemiladiciannove, alle ore 15,00, in Torino, C.so Inghilterra 7, nella Sala “Auditorium” della Città Metropolitana di Torino, sotto la Presidenza della Sindaca Metropolitana Chiara APPENDINO e con la partecipazione della Segretaria Generale Daniela Natale si è riunita la Conferenza Metropolitana come dall’avviso del 31 maggio 2019 recapitato nel termine legale - insieme con l'Ordine del Giorno - ai singoli componenti della Conferenza Metropolitana e pubblicato all'Albo Pretorio on-line. Sono intervenuti i seguenti componenti la Conferenza Metropolitana: COMUNE RESIDENTI AGLIE’ SINDACO SUCCIO MARCO 2.644 AVIGLIANA SINDACO ARCHINA’ ANDREA 12.129 BARBANIA VICE SINDACO COSTANTINO MARIA 1.623 BEINASCO VICE SINDACO LUMETTA ELENA 18.104 BOLLENGO SINDACO RICCA LUIGI SERGIO 2.112 BORGONE SUSA VICE SINDACO ROLANDO ANDREA 2.320 BRICHERASIO VICE SINDACO MERLO ILARIO 4.517 BROZOLO VICE SINDACO BONGIOVANNI SERGIO 471 BRUINO VICE SINDACO VERDUCI ANELLO 8.479 BUTTIGLIERA ALTA VICE SINDACO SACCENTI LAURA 6.386 CAFASSE VICE SINDACO AIMAR SERGIO 3.511 CALUSO VICE SINDACO CHIARO LUCA 7.483 CAMBIANO SINDACO VERGNANO CARLO 6.215 CAMPIGLIONE FENILE VICE SINDACO RISSO MARIA 1.382 CANDIA CANAVESE VICE SINDACO LA MARRA UMBERTO 1.286 CANTOIRA VICE SINDACO OLIVETTI CELESTINA 554 CARMAGNOLA SINDACO GAVEGLIO IVANA 28.563 CASELETTE VICE SINDACO GIORGIO MOTRASSINO 2.931 CASELLE TORINESE SINDACO BARACCO LUCA