“The Poor Men of Lyon”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy

The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy: Through the Eyes Adam Giancola of the Waldensian Experience The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy: Through the Eyes of the Waldensian Experience Adam Giancola In the wake of the Protestant Reformation, the experience of many countries across Europe was the complete overturning of traditional institutions, whereby religious dissidence became a widespread phenomenon. Yet the focus on Reformation history has rarely been given to countries like Italy, where a strong Catholic presence continued to persist throughout the sixteenth century. In this regard, it is necessary to draw attention to the ‘Italian Reformation’ and to determine whether or not the ideas of the Reformation in Western Europe had any effect on the religious and political landscape of the Italian peninsula. In extension, there is also the task to understand why the Reformation did not ‘succeed’ in Italy in contrast to the great achievements it made throughout most other parts of Western Europe. In order for these questions to be addressed, it is necessary to narrow the discussion to a particular ‘Protestant’ movement in Italy, that being the Waldensians. In an attempt to provide a general thesis for the ‘failure’ of the Protestant movement throughout Italy, a particular look will be taken at the Waldensian case, first by examining its historical origins as a minority movement pre-dating the European Reformation, then by clarifying the Waldensian experience under the sixteenth century Italian Inquisition, and finally, by highlighting the influence of the Counter-Reformation as pivotal for the future of Waldensian survival. Perhaps one of the reasons why the Waldensian experience differed so greatly from mainstream European reactions has to do with its historical development, since in many cases it pre-dated the rapid changes of the sixteenth century. -

Forerunners to the Reformation

{ Lecture 19 } FORERUNNERS TO THE REFORMATION * * * * * Long before Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the Wittenberg Door, there were those who recognized the corruption within the Roman Catholic Church and the need for major reform. Generally speaking, these men attempted to stay within the Catholic system rather than attempting to leave the church (as the Protestant Reformers later would do). The Waldensians (1184–1500s) • Waldo (or Peter Waldo) lived from around 1140 to 1218. He was a merchant from Lyon. But after being influenced by the story of the fourth-century Alexius (a Christian who sold all of his belongings in devotion to Christ), Waldo sold his belongings and began a life of radical service to Christ. • By 1170, Waldo had surrounded himself with a group of followers known as the Poor Men of Lyon, though they would later become known as Waldensians. • The movement was denied official sanction by the Roman Catholic Church (and condemned at the Third Lateran Council in 1179). Waldo was excommunicated by Pope Lucius III in 1184, and the movement was again condemned at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. • Waldensians were, therefore, persecuted by the Roman Catholics as heretics. However, the movement survived (even down to the present) though the Waldensians were often forced into hiding in the Alps. • The Waldensian movement was characterized by (1) voluntary poverty (though Waldo taught that salvation was not restricted to those who gave up their wealth), (2) lay preaching, and (2) the authority of the Bible (translated in the language of the people) over any other authority. -

Cathar Or Catholic: Treading the Line Between Popular Piety and Heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271

Cathar or Catholic: Treading the line between popular piety and heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271. Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of History William Kapelle, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master’s Degree by Elizabeth Jensen May 2013 Copyright by Elizabeth Jensen © 2013 ABSTRACT Cathar or Catholic: Treading the line between popular piety and heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271. A thesis presented to the Department of History Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Elizabeth Jensen The Occitanian Cathars were among the most successful heretics in medieval Europe. In order to combat this heresy the Catholic Church ordered preaching campaigns, passed ecclesiastic legislation, called for a crusade and eventually turned to the new mechanism of the Inquisition. Understanding why the Cathars were so popular in Occitania and why the defeat of this heresy required so many different mechanisms entails exploring the development of Occitanian culture and the wider world of religious reform and enthusiasm. This paper will explain the origins of popular piety and religious reform in medieval Europe before focusing in on two specific movements, the Patarenes and Henry of Lausanne, the first of which became an acceptable form of reform while the other remained a heretic. This will lead to a specific description of the situation in Occitania and the attempts to eradicate the Cathars with special attention focused on the way in which Occitanian culture fostered the growth of Catharism. In short, Catharism filled the need that existed in the people of Occitania for a reformed religious experience. -

The Protestant Reformation • a Period of Time in Europe When People

The Protestant Reformation A period of time in Europe when people wanted _______________________ _______________________________________________________________ Beginning as early as the __________, but officially began in the __________ thanks to Martin Luther Will lead to changes within the Catholic Church as well as many European Nations and its leaders Without the ____________________________________________________, none of this would have been possible (the first copy machine basically) Printing Press Video Questions 1. When was the printing press invented? 2. What affect did the printing press have on human culture? 3. What were some of the troubles with printing presses? 4. How many pages could be printed in one hour? 5. Where do the names “uppercase” and “lowercase” come from? Why change the church? The Catholic Church ____________________________________ in the 1500s Most of the Church and powerful __________ (_______________________) had become ________________. People did not like to see the ___________________________ of the church The people had a strong desire to ___________________________________ Setting the Stage Video Questions 1. What does “catholic” mean? 2. Who is the head of the Catholic church? 3. Where do we get the term “holidays” from? 4. Who was the Pope in 1517? 5. Indulgences could get you time off from where? Why didn't they care earlier than the 1500s? This corruption had been going on since the ___________________________ ....Why care now?? As the Renaissance progressed, more and more people _________________ -

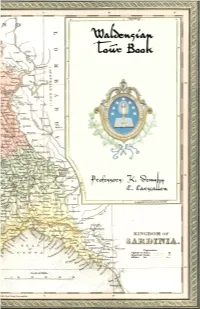

Waldensian Tour Guide

1 ii LUX LUCET EN TENEBRIS The words surrounding the lighted candle symbolize Christ’s message in Matthew 5:16, “Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your father who is in heaven.” The dark blue background represents the night sky and the spiritual dark- ness of the world. The seven gold stars represent the seven churches mentioned in the book of Revelation and suggest the apostolic origin of the Waldensian church. One oak tree branch and one laurel tree branch are tied together with a light blue ribbon to symbolize strength, hope, and the glory of God. The laurel wreath is “The Church Triumphant.” iii Fifth Edition: Copyright © 2017 Original Content: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout Redesign:Luis Rios First Edition Copyright © 2011 Published by: School or Architecture Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI 49104 Compiled and written: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout and Design: Kathleen Demsky & David Otieno Credits: Concepts and ideas are derived from my extensive research on this history, having been adapted for this work. Special credit goes to “The Burning Bush” (Captain R. M. Stephens) and “Guide to the Trail of Faith” (Maxine McCall). Where there are direct quotes I have given credit. Web Sources: the information on the subjects of; Fortress Fenestrelle, Arch of Augustus, Fortress of Exhilles and La Reggia Veneria Reale ( Royal Palace of the Dukes of Savoy) have been adapted from GOOGLE searches. Please note that some years the venue will change. iv WALDENSIAN TOUR GUIDE Fifth EDITION BY KATHLEEN M. DEMSKY v Castelluzzo April 1655 Massacre and Surrounding Events, elevation 4450 ft The mighty Castelluzzo, Castle of Light, stands like a sentinel in the Waldensian Valleys, a sacred monument to the faith and sacrifice of a people who were willing to pay the ultimate price for their Lord and Savior. -

Seeking Primitive Christianity in the Waldensian Valleys

NR 904 02:28:2006 11:53 AM Page 5 Seeking Primitive Christianity in the Waldensian Valleys Protestants, Mormons, Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses in Italy Michael W. Homer ABSTRACT: During the nineteenth century, Protestant clergymen (Anglican, Presbyterian, and Baptist) as well as missionaries for new reli- gious movements (Mormons, Seventh-day Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses) believed that Waldensian claims to antiquity were important in their plans to spread the Reformation to Italy. The Waldensians, who could trace their historical roots to Valdes in 1174, developed an ancient origins thesis after their union with the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century. This thesis held that their community of believers had preserved the doctrines of the primitive church. The competing churches of the Reformation believed that the Waldensians were “destined to fulfill a most important mission in the Evangelization of Italy” and that they could demonstrate, through Waldensian history and practices, that their own claims and doctrines were the same as those taught by the primitive church. The new religious movements believed that Waldensians were the best prepared in Italy to accept their new revelations of the restored gospel. In fact, the initial Mormon, Seventh-day Adventist, and Jehovah’s Witness converts in Italy were Waldensians. By the end of the century, however, Catholic, Protestant, and Waldensian scholars had debunked the thesis that Waldensians were proto-Protestants prior to Luther and Calvin. n June 1850 Mormon Apostle Lorenzo Snow (1814–1901) opened the Italian Mission in the Kingdom of Sardinia. He chose this location Ibecause he believed, based on a tract he read in England, that the Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Volume 9, Issue 4, pages 5–33, ISSN 1092-6690 (print), 1541–8480 (electronic). -

Trinitarian/Christological Heresies Heresy Description Origin Official

Trinitarian/Christological Heresies Official Heresy Description Origin Other Condemnation Adoptionism Belief that Jesus Propounded Theodotus was Alternative was born as a by Theodotus of excommunicated names: Psilanthro mere (non-divine) Byzantium , a by Pope Victor and pism and Dynamic man, was leather merchant, Paul was Monarchianism. [9] supremely in Rome c.190, condemned by the Later criticized as virtuous and that later revived Synod of Antioch presupposing he was adopted by Paul of in 268 Nestorianism (see later as "Son of Samosata below) God" by the descent of the Spirit on him. Apollinarism Belief proposed Declared to be . that Jesus had by Apollinaris of a heresy in 381 by a human body Laodicea (died the First Council of and lower soul 390) Constantinople (the seat of the emotions) but a divine mind. Apollinaris further taught that the souls of men were propagated by other souls, as well as their bodies. Arianism Denial of the true The doctrine is Arius was first All forms denied divinity of Jesus associated pronounced that Jesus Christ Christ taking with Arius (ca. AD a heretic at is "consubstantial various specific 250––336) who the First Council of with the Father" forms, but all lived and taught Nicea , he was but proposed agreed that Jesus in Alexandria, later exonerated either "similar in Christ was Egypt . as a result of substance", or created by the imperial pressure "similar", or Father, that he and finally "dissimilar" as the had a beginning declared a heretic correct alternative. in time, and that after his death. the title "Son of The heresy was God" was a finally resolved in courtesy one. -

Protestant Propaganda in a Cold War of Religion: from the Hartlib Circle to the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge Sugiko Nishikawa

LITHUANIAN historical STUDIES 16 2011 ISSN 1392-2343 PP. 51–59 PROTESTANT PROPAGANDA IN A COLD War OF RELIGION: FROM THE HARTLIB CIRCLE TO THE SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE Sugiko Nishikawa ABSTRACT This article considers how, impelled by confessional divisions caused by the Reformation, a general sense of pan-Protestant community grew across Europe, and its members launched a long battle against Ro- man Catholicism far beyond the 16th century. Indeed, it continued into the mid-18th century, the so-called Age of Reason. If it cannot necessarily be described as an open war of religion like the Thirty Years War, it was at least a cold war. From their points of view, the Protestant minorities threat- ened by the Roman Catholic Counter Reformation, such as the Waldensi- ans in northern Italy and the Lithuanian Calvinists, stood on the front line in this war. Thus, financial support was regularly offered by the Protestant churches in Great Britain and Ireland to their distressed brethren across the continent, university scholarships were set up for students from Catholic- dominated areas, and plans were drafted for a Protestant union in Europe, from a military level to an ecclesiastical one. It is in this context that we must understand how apparently strange a phenomenon as British support for the translation of the Bible into Lithuanian developed. The author sees Chylinski’s activities in the tradition of learning and charity exhibited in the 1650s by the three leading members of the Hartlib philosophical circle, namely, Samuel Hartlib (originally from Elbing), Jan Amos Comenius (from Moravia), and John Dury (born in Edinburgh, he spent his early life in vari- ous places in northern Europe), who were, in a sense, Protestant refugees to England from north-central Europe. -

Cromwelliana

CROMWELLIANA Published by The Cromwell Association, a registered charity, this Cromwelliana annual journal of Civil War and Cromwellian studies contains articles, book reviews, a bibliography and other comments, contributions and III Series papers. Details of availability and prices of both this edition and previous editions of Cromwelliana are available on our website: The Journal of www.olivercromwell.org. The 2018 Cromwelliana Cromwell Association The Cr The omwell Association omwell No 1 ‘promoting our understanding of the 17th century’ 2018 The Cromwell Association The Cromwell Museum 01480 708008 Grammar School Walk President: Professor PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS Huntingdon www.cromwellmuseum.org PE29 3LF Vice Presidents: PAT BARNES Rt Hon FRANK DOBSON, PC Rt Hon STEPHEN DORRELL, PC The Cromwell Museum is in the former Huntingdon Grammar School Dr PATRICK LITTLE, PhD, FRHistS where Cromwell received his early education. The Cromwell Trust and Professor JOHN MORRILL, DPhil, FBA, FRHistS Museum are dedicated to preserving and communicating the assets, legacy Rt Hon the LORD NASEBY, PC and times of Oliver Cromwell. In addition to the permanent collection the Dr STEPHEN K. ROBERTS, PhD, FSA, FRHistS museum has a programme of changing temporary exhibitions and activities. Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA Opening times Chairman: JOHN GOLDSMITH Honorary Secretary: JOHN NEWLAND April – October Honorary Treasurer: GEOFFREY BUSH Membership Officer PAUL ROBBINS 11.00am – 3.30pm, Tuesday – Sunday The Cromwell Association was formed in 1937 and is a registered charity (reg no. November – March 1132954). The purpose of the Association is to advance the education of the public 1.30pm – 3.30pm, Tuesday – Sunday (11.00am – 3.30pm Saturday) in both the life and legacy of Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658), politician, soldier and statesman, and the wider history of the seventeenth century. -

Waldensians and Franciscans a Comparative Study of Two Reform Movements in the Late Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1971 Waldensians and Franciscans a Comparative Study of Two Reform Movements in the Late Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries Stanley D. Pikaart Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pikaart, Stanley D., "Waldensians and Franciscans a Comparative Study of Two Reform Movements in the Late Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries" (1971). Master's Theses. 2906. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/2906 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WALDENSIANS AND FRANCISCANS A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TWO REFORM MOVEMENTS IN THE LATE TWELFTH AND EARLY THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Stanley D, Pikaart A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August, 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks and appreciations are extended to profes sors Otto Grundler of the Religion department and George H. Demetrakopoulos of the Medieval Institute for their time spent in reading this paper. I appreciate also the help and interest of Mrs. Dugan of the Medieval Institute. I cannot express enough my thanks to Professor John Sommer- feldt for his never-ending confidence and optimism over the past several years and for his advice and time spent going over in detail the several drafts of this paper. -

Lorraine Simonis

The Kingdom, the Power and the Glory: the Albigensian Crusade and the Subjugation of the Languedoc A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Bachelor of Arts Degree with Honors in Medieval and Renaissance Studies Lorraine Marie Alice Simonis Washington and Lee University April 11, 2014 David Peterson, Advisor Alexandra Brown, Second Reader 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 4 Notes 5 Timeline 7 Illustrations 9 Introduction 12 Chapter 1: “The Little Foxes Spoiling the Vineyard of the Lord” 17 Religious Dissent The Medieval Church and Heresy Cathar History and Cosmology Chapter 2: “The Practical Consequences of Catharism” 30 The Uniqueness of the Cathars Cathars and Clerics The Popular Appeal of Catharism Chapter 3: “The Chief Source of the Poison of Faithlessness” 39 The Many Faces of “Feudalism” Chivalric Society vs. Courtly Society The Political Structure of the South The Southern Church Chapter 4: “The Business of the Peace and of the Faith” 54 The Conspicuous Absence of the Albigensians A Close Reading of the Statutes of Pamiers and the Charter of Arles Pamiers Arles Conclusion 66 3 Bibliography 72 Primary Sources Secondary Sources 4 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I’d like to thank my readers, Profs. Peterson and Brown, for all of their guidance and support – not only in writing this thesis, but throughout my time at Washington & Lee. If it weren’t for Prof. Peterson, who introduced me to the Medieval & Renaissance Studies program while I was still a prospective student, I may never have developed an interest in this topic in the first place. Thanks also to all the professors who’ve made my time here at Washington & Lee so special and successful, especially Profs. -

First Corinthians Sermon Study Equipping Class

Summit Woods Baptist Church First Corinthians Sermon Study Equipping Class The Significance of the Reformation This week’s lesson involves more reading, so we have divided it up over four days instead of the usual three. Please begin your study early in the week. On Sunday, Pastor Bret will close out the Elders’ The Five Solas of the Reformation series with a sermon on “The Significance of the Reformation.” During the month of October, Desiring God has been posting short biographical sketches on several of the key individuals involved in the Reformation. For this week’s homework, we will be considering the example of some of the reformers highlighted so far in their “Here We Stand” website posts. We have provided the biographical sketches for this homework at the end of this packet. You can find the full series of biographical sketches at www.desiringgod.org/series/here-we-stand. We encourage you to read the rest of the biographies in the coming days, but our class discussions will focus on the ones listed below. Homework Structure Names like Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli quickly come to mind when thinking about the origins of the Protestant Reformation, but these men were not alone in their convictions. In reading through the brief biographical sketches of some of the other men and women engaged in the leading the Reformation, some consistent themes emerge. Several of these themes are listed on the following pages. As you read the biographical sketches listed for each day (provided at the end of the homework packet), record how you see these people living out these themes, and come to class prepared to discuss your observations.