Wheels of Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emerging Mobility Technologies and Trends

Emerging Mobility Technologies and Trends And Their Role in Creating “Mobility-As-A-System” For the 21st Century and Beyond OWNERSHIP RIGHTS All reports are owned by Energy Systems Network (ESN) and protected by United States copyright and international copyright/intellectual property laws under applicable treaties and/or conventions. User agrees not to export any report into a country that does not have copyright/ intellectual property laws that will protect ESN’s rights therein. GRANT OF LICENSE RIGHTS ESN hereby grants user a non-exclusive, non-refundable, non- transferable Enterprise License, which allows you to (i) distribute the report within your organization across multiple locations to its representatives, employees or agents who are authorized by the organization to view the report in support of the organization’s internal business purposes; and (ii) display the report within your organization’s privately hosted internal intranet in support of your organization’s internal business purposes. Your right to distribute the report under an Enterprise License allows distribution among multiple locations or facilities to Authorized Users within your organization. ESN retains exclusive and sole ownership of this report. User agrees not to permit any unauthorized use, reproduction, distribution, publication or electronic transmission of any report or the information/forecasts therein without the express written permission of ESN. DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY AND LIABILITY ESN has used its best efforts in collecting and preparing each report. ESN, its employees, affi liates, agents, and licensors do not warrant the accuracy, completeness, correctness, non-infringement, merchantability, or fi tness for a particular purpose of any reports covered by this agreement. -

BBP Employee Handbook

Boise Bicycle Project Employee Handbook 2010 Edition Boise Bicycle Project- Volunteer Handbook Introductory Letter Welcome to Boise Bicycle Project! I can still remember waking up early on Christmas morning in 1986, the 4 th year of my life. I actually don’t think I even fell asleep that night. I knew I was getting a bicycle, it was the only thing I asked for, and the only thing I wanted. When I ran into the family room and looked under the tree, there it was, my very first bike. It was a white and black BMX bike with off road tires and Murray written on the side in bright red letters. I had just received my first key to the world; the adventures to come would be limitless. The idea of Boise Bicycle Project (BBP) originated from Co-founder Brian Anderson and my shared passion for cycling and shared dissatisfaction with Boise’s incomplete cycling community. We knew there must be other people in Boise who felt the same way, we knew Boise needed a community ran bicycle cooperative that would offer bicycles and bicycle education to everyone regardless of income, and we knew that with the help of the community, we could make it happen. In October 2007 Brian and I purchased 60 bicycles from the Boise Youth Ranch for $20. We began fixing them out of a 200 sq. ft. studio apartment and distributing them to children of low-income families. Soon, the word caught on and we quickly out grew the small studio. The community began sending us all of their old bikes, and volunteers began to pour in. -

The Poetry Lady of Del

Alexandria Times Vol. 15, No. 14 Alexandria’s only independent hometown newspaper. APRIL 4, 2019 The poetry lady of Del Ray The giving Renée season Renée Adams celebrates 10 Adams years of her poetry fence began Alexandria businesses put pinning the “community” in “busi- BY MISSY SCHROTT poetry, ness community” pictures, To know Renée Adams is to know comics BY CODY MELLO-KLEIN her love of poetry, and in Del Ray, and her name is inextricably linked with quotes Thousands of residents donate on the mention of her poetry fence. to local nonprofits both during fence This month, Adams is celebrating border- ACT for Alexandria’s Spring2AC- the 10-year anniversary of the land- ing her Tion – for which early giving is mark poetry fence. But in the past yard in already underway leading up to decade, she’s done more than pro- 2009. the April 10 day of giving – and vide neighbors and passersby with a PHOTO/ throughout the year. MISSY But philanthropy in Alexan- SEE POETRY | 12 SCHROTT dria is not limited to individuals and families; many of the city’s businesses are integrated into Al- exandria’s fabric and give back to Murder case Mirror, Mirror the community in ways both big and small. Alexandria’s thriving, hyper- mistrial local community of restaurants, Defendant thought victim was werewolf SEE GIVING | 16 BY CODY MELLO-KLEIN INSIDE An Alexandria judge de- Parks clared a mistrial on March 27 in Angel Park has lengthy past, the murder case of a man who soggy present. claimed he thought his victim Page 6 was a werewolf, according to Commonwealth’s Attorney Bryan Business Porter. -

STUDY of ELECTRIC SCOOTERS Markets, Cases and Analyses STUDY of ELECTRIC SCOOTERS Markets, Cases and Analyses

STUDY OF ELECTRIC SCOOTERS Markets, cases and analyses STUDY OF ELECTRIC SCOOTERS Markets, cases and analyses Study prepared by Sidera Consult at the request of the German Cooperation, through the GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH) and the Ministry of Economy (ME). Authors: Carolina Ures Daniel Guth Diego Ures Victor Andrade Ministry of Economy January 2020 FEDERATIVE REPUBLIC OF BRAZIL Presidency of the Republic Jair Messias Bolsonaro Minister of Economy Paulo Roberto Nunes Guedes Special Secretary for Productivity, Employment and Competitiveness Carlos Alexandre da Costa Secretary for Development of Industry, Trade, Services and Innovation Gustavo Leipnitz Ene Technical support Cooperação Alemã para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável por meio da Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH National Director Michael Rosenauer Project director Jens Giersdorf COORDINATION AND IMPLEMENTATION Coordination and operation staff Proofreading ME - André Sequeira Tabuquini, Bruno de Almeida Ribeiro, Ana Terra Gustavo Duarte Victer, Marcelo Vasconcellos de Araújo Lima, Ricardo Zomer e Thomas Paris Caldellas Layout design GIZ - Anna Palmeira, Bruno Carvalho, Fernando Sources, Marcus Barbara Miranda Regis e Jens Giersdorf Translation Authors Enrique Villamil Carolina Ures, Daniel Guth, Diego Ures e Victor Andrade PUBLICADO POR Technical coordination Efficient Propulsion Systems Project – PROMOB-e (Bilateral Carolina Ures (Sidera) e Fernando Sources (GIZ) Technical Cooperation Project between the Secretariat of Development of the Industry, Trade, Services and Innovation Technical review - SDIC and the German Cooperation for Sustainable Fernando Sources (GIZ) Development (GIZ) CONTACTS SDCI/Ministry of Economy Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit Esplanada dos Ministérios BL J - Zona Cívico-Administrativa, (GIZ) GmbH CEP: 70053-900, Brasília - DF, Brasil. SCN Quadra 1 Bloco C Sala 1501 – 15º andar Ed. -

Networking Transportation

Networking Transportation April 2017 CONNECTIONS G R E A TER PHIL A D ELPHI A E N G A GE, C OLL A B O R A T E , ENV I S ION The Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission is dedicated to uniting the region’s elected officials, planning professionals, and the public with a common vision of making a great region even greater. Shaping the way we live, work, and play, DVRPC builds consensus on improving transportation, promoting smart growth, protecting the environment, and enhancing the economy. We serve a diverse region of nine counties: Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery, and Philadelphia in Pennsylvania; and Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, and Mercer in New Jersey. DVRPC is the federally designated Metropolitan Planning Organization for the Greater Philadelphia Region — leading the way to a better future. The symbol in our logo is adapted from the official DVRPC seal and is designed as a stylized image of the Delaware Valley. The outer ring symbolizes the region as a whole while the diagonal bar signifies the Delaware River. The two adjoining crescents represent the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the State of New Jersey. DVRPC is funded by a variety of funding sources including federal grants from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA), the Pennsylvania and New Jersey departments of transportation, as well as by DVRPC’s state and local member governments. The authors, however, are solely responsible for the findings and conclusions herein, which may not represent the official views or policies of the funding agencies. -

THE PROMISE and PITFALLS of E-SCOOTER SHARING by Daniel Schellong, Philipp Sadek, Carsten Schaetzberger, and Tyler Barrack

THE PROMISE AND PITFALLS OF E-SCOOTER SHARING By Daniel Schellong, Philipp Sadek, Carsten Schaetzberger, and Tyler Barrack f market growth were vehicle Why the E-Scooter? Iacceleration, the humble electric Still in their infancy, the biggest names in scooter—the latest answer to urban e-scooter sharing—Bird and Lime—have mobility—would be a Ferrari. Since their each amassed hundreds of millions of debut (by US-based Bird) in the fall of 2017, dollars in funding. Many more startups shared e-scooters are now in service in have raised more than $20 million each. hundreds of cities worldwide, and more (See Exhibit 1.) How to explain this launches are planned in the coming explosion and the forecasts of eye-popping months. A dozen e-scooter startups have growth worldwide? already attracted more than $1.5 billion in funding, and we estimate that the global The rapid rise of shared mobility—through market will reach about $40 billion to ride hailing, car sharing, and shared public $50 billion by 2025. bicycle systems—paved the way for e-scooters, responding to the public’s But several factors will put the brakes on appetite for cheap, convenient, and flexible e-scooter growth, if they haven’t already. ways to quickly get around increasingly Right now, the unit economics don’t add congested cities. But even beyond the up, and with so crowded a field, consol- practicality of e-scooters is the element of idation is inevitable. So is greater reg- fun that they offer: anyone—whether an ulation: as e-scooters proliferate, cities executive in a suit or a student in jeans— need to sort out traffic rules, public safety, can enjoy feeling like a little kid again. -

Cycle to Work Scheme

Cycle to work scheme Frequently asked questions Below are some questions and answers that you may find of interest when considering whether to participate in the Cycle to Work Scheme. 1. What is the Cycle to Work scheme? The Cycle to Work scheme was introduced by the Department for Transport. The Government allows employees to hire bikes and certain related safety equipment on a tax-free basis known as salary sacrifice scheme (see point 2). The Cycle to Work scheme helps to promote healthier journeys to work, and reduce environmental pollution. The University works with Edinburgh Bicycle Co-operative in order to make the scheme available to staff. 2. What is a salary sacrifice scheme? Under a salary sacrifice arrangement an employee gives up the right to part of his or her salary and receives a non-cash benefit from the employer in return which will not be subject to tax or national insurance deductions. Further details about salary sacrifice are available on the HMRC website at: http://www.hmrc.gov.uk/specialist/salary_sacrifice.pdf 3. How long is the hire period? The hire period is fixed for a period of 48 months. HMRC have issued guidance to provide a simplified method for the valuation of bikes at the end of the hire period, in the form of a ‘Valuation Table’. The hire period of 48 months has therefore chosen to minimise the market value payment, payable by you, at the end of the hire agreement period and is not negotiable. Deductions from your monthly salary will, where possible, start from the first salary payment after you signed the hire agreement. -

Interoperability of Heterogeneous Iot Platforms D 2.1 Stakeholders and Market Analysis Report

Interoperability of Heterogeneous IoT Platforms D 2.1 Stakeholders and market analysis report Editor: AFT, ValenciaPort Foundation Deliverable nature: Document, Report (R) Dissemination level: Public (PU) Date: planned | actual 31 March 2016 31 March 2016 Version | no. of pages Version 1.1 377 Keywords: Stakeholder, Market Analysis INTER-IoT Deliverable D2.1 Disclaimer This document contains material, which is the copyright of certain INTER-IoT consortium parties, and may not be reproduced or copied without permission. The information contained in this document is the proprietary confidential information of the INTER-IoT consortium (including the Commission Services) and may not be disclosed except in accordance with the consortium agreement. The commercial use of any information contained in this document may require a license from the proprietor of that information. Neither the project consortium as a whole nor a certain party of the consortium warrant that the information contained in this document is capable of use, nor that use of the information is free from risk, and accepts no liability for loss or damage suffered by any person using this information. The information in this document is subject to change without notice. The INTER-IoT Consortium Universitat Politécnica de Valencia, UPV, Spain Telecom Italia S.p.A., TI, Italy Università della Calabria, UNICAL, Italy Provedelop S. L., PRO, Spain Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, TU/e, Netherlands Fundación de la Comunidad Valenciana para la Investigación, Promoción y Estudios Comerciales -

Pedal Peak District Final Report

Pedal Peak District Final Report December 2009 – March 2011 Description Pedal Peak District was the Peak District National Park Authority’s premier cycling development project, funded and supported by the Department for Transport and Cycling England, from December 2009 to 31 March 2011. The project was fully supported by Derbyshire County Council, High Peak Borough Council, Derbyshire Dales District Council and Visit Peak District. Pedal Peak District has delivered significant infrastructure development and a social marketing programme. The Infrastructure work constituted a major element of this project. At the time of writing a great deal has been achieved and the works are still continuing for a late spring 2011 opening. The four closed tunnels have been cleared, surveyed and repaired and the entrance doors removed. Work is currently taking place to install a power supply and lighting. The tunnels, structures and a large proportion of the trail is also to be resurfaced and the access improved at Blackwell Mill Cottages, Great Longstone and Coombs Road. New signs will be put up on the trail, along with interpretation about the new route. This will include listening posts outlining the history of the tunnels. This work has involved the balancing of a large number of needs including detailed consideration of the unique landscape, conservation and heritage features of the trail, tunnels and the surrounding area. These features, and the issues that they raise, together with the limited project timescale have meant that the full link to Buxton through Woo Dale cannot be achieved in the project term. Planning consent has been achieved, through Peak Cycle Links, for a section of route to the north of Buxton at Staker Hill. -

Planning for Shared Mobility

PAS REPORTPAS 583 P LANNING FOR SHARED MOBILITY American Planning Association 205 N. Michigan Ave., Suite 1200 Chicago, IL 60601-5927 planning.org | Cohen and Shaheen and Cohen PAS REPORT 5 8 3 A MERICAN PLANNING ASSOCIATION PLANNING FOR SHARED MOBILITY Adam Cohen and Susan Shaheen POWER TOOLS ABOUT THE AUTHORS APA RESEARCH MISSION Adam Cohen is a shared mobility researcher at the Transporta- tion Sustainability Research Center at the University of California, APA conducts applied, policy-relevant research Berkeley. Since joining the group in 2004, his research has focused that advances the state of the art in planning on shared mobility and emerging technologies. He has coauthored practice. APA’s National Centers for Plan- numerous articles and reports on shared mobility in peer-reviewed ning—the Green Community Research Center, journals and conference proceedings. His academic background is the Hazards Planning Research Center, and the in city and regional planning and international affairs. Planning and Community Health Research PAS SUBSCRIBERS GET EVERY NEW PAS REPORT, PLUS Center—guide and advance a research direc- Susan Shaheen is an adjunct professor in the Department of Civil THESE RESOURCES FOR EVERYONE IN THE OFFICE TO SHARE tive that addresses important societal issues. and Environmental Engineering and a research engineer with the APA’s research, education, and advocacy pro- Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, grams help planners create communities of Berkeley. She is also co-director of the Transportation Sustainabil- PAS Reports Archive PAS QuickNotes lasting value by developing and disseminating ity Research Center at UC Berkeley. She was the policy and behav- Free online access for subscribers Bite-size backgrounders on planning basics information, tools, and applications for built ioral research program leader at California Partners for Advanced and natural environments. -

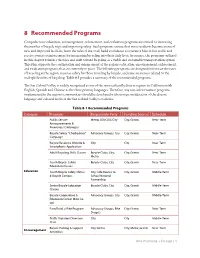

8 Recommended Programs

8 Recommended Programs Comprehensive education, encouragement, enforcement, and evaluation programs are critical to increasing the number of bicycle trips and improving safety. Such programs ensure that more residents become aware of new and improved facilities, learn the rules of the road, build confidence to operate a bike in live traffic and receive positive reinforcement for integrating bicycling into their daily lives. In essence, the programs outlined in this chapter reinforce the idea and shift toward bicycling as a viable and sustainable transportation option. This Plan supports the continuation and enhancement of the region’s education, encouragement, enforcement, and evaluation programs that are currently in place. The following programs are designed to increase the rates of bicycling in the region, increase safety for those traveling by bicycle, and raise awareness related to the multiple benefits of bicycling. Table 8-1 provides a summary of the recommended programs. The San Gabriel Valley is widely recognized as one of the most culturally diverse regions in California with English, Spanish and Chinese as the three primary languages. Therefore, any non-infrastructure programs implemented in the region’s communities should be developed with strong consideration of the diverse language and cultural needs of the San Gabriel Valley’s residents. Table 8-1 Recommended Programs Category Program Responsible Party Funding Source Schedule Public Service Metro; SGVCOG; City City; Grants Near-Term Announcements & Awareness Campaigns Bicycle -

San Gabriel Valley Regional Bicycle Master Plan

San Gabriel Valley Regional Bicycle Master Plan November 2014 PREPARED BY: Alta Planning + Design PREPARED FOR: ALTA PLANNING +DESIGN Cities of Baldwin Park, El Monte, Monterey Park, San Gabriel, and South El Monte SAN GABRIEL VALLEY REGIONAL BICYCLE MASTER PLAN Volunteers & Interns San Gabriel Valley Regional Bicycle Master Plan Lisa Greenquist, Azusa Paci c University Bill Chi, University of California, Los Angeles Albert Chao, California Polytechnic University, Pomona Made possible with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Los Angeles County Department of Stephanie Hsieh, Adjunct Professor, University of Southern California Public Health. Andrew Fung Yip, Azusa Paci c University Jackson Lam, California Polytechnic University, Pomona ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Amy Wong, University of California, Berkeley Jonathan Rodriguez, Claremont Graduate University Bicycle Master Plan Blue Ribbon Committee Manuel Lozano, Mayor, Baldwin Park Cruz Baca, Council Member, Baldwin Park Victoria Martinez, Council Member, El Monte Peter Chan, Council Member, Monterey Park Vincent Chang, City Clerk, Monterey Park Kevin Sawkins, Council Member, San Gabriel Louie Aguiñaga, Mayor, South El Monte Joe Gonzalez, Council Member, South El Monte Technical Advisory Committee Daniel Wall, Director of Public Works, Baldwin Park David Lopez, Associate Engineer, Baldwin Park Cesar Roldan, Senior Engineer, El Monte Amy Ho, City Clerk, Monterey Park Cesar Vega, Engineer, Monterey Park Daren Grilley, Public Works Director/City Engineer, San Gabriel