The Economic Botany Collection at Kew: Analysis of Accessions Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duke University Dissertation Template

A Sea of Debt: Histories of Commerce and Obligation in the Indian Ocean, c. 1850-1940 by Fahad Ahmad Bishara Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Edward J. Balleisen, Co-supervisor ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Co-supervisor ___________________________ Janet J. Ewald ___________________________ Timur Kuran ___________________________ Bruce S. Hall ___________________________ Jonathan K. Ocko Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 i v ABSTRACT A Sea of Debt: Histories of Commerce and Obligation in the Indian Ocean, c. 1850-1940 by Fahad Ahmad Bishara Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Edward J. Balleisen, Co-supervisor ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Co-supervisor ___________________________ Janet J. Ewald ___________________________ Timur Kuran ___________________________ Bruce S. Hall ___________________________ Jonathan K. Ocko An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 Copyright by Fahad Ahmad Bishara 2012 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a legal history of debt and economic life in the Indian Ocean during the nineteenth and early-twentieth century. It draws on materials from Bahrain, Muscat, Bombay, Zanzibar and London to examine how members of an ocean-wide commercial society constructed relationships of economic mutualism with one another by mobilizing debt and credit. It further explores how they expressed their debt relationships through legal idioms, and how they mobilized commercial and legal instruments to adapt to the emergence of modern capitalism in the region. -

William Astor Chanler (1867-1934) Und Ludwig Von Höhnel (1857-1942) Und Afrika“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „William Astor Chanler (1867-1934) und Ludwig von Höhnel (1857-1942) und Afrika“ Verfasser Dr. Franz Kotrba Angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosphie aus der Studienrichtung Geschichte Wien, im September 2008 Studienrichtung A 312 295 Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Walter Sauer Für Irene, Paul und Stefanie Inhaltsverzeichnis William Astor Chanler (1867-1934) und Ludwig von Höhnel (1857-1942) und Afrika Vorbemerkung………………………………………………………………………..2 1. Einleitung…………………………………………………………………………..6 2. Höhnel und Afrika……………………………………………………………...13 3. William Astor Chanler und Afrika…………………………………………..41 4. Der historische Hintergrund. Der Sultan von Zanzibar verliert sein Land, 1886-1895…………………………………………………………………………...56 5. Jagdreise um den Kilimanjaro…………………………………………….…83 6. Chanlers und Höhnels „Forschungsreise“ 1893/4. Eine Episode in der frühen Kolonialgeschichte Kenyas. 6.1. Motivation und Zielsetzung……………………………………………….114 6.2. Kenya Anfang der 1890er Jahre…………………………………………124 6.3. Der Tana River – ein Weg zur Erschließung British Ostafrikas?...134 6.4. Zum geheimnisvollen Lorian See………………………………………..153 6.5. Die Menschen am Lorian………………………………………………….161 6.6. Im Lande der Meru………………………………………………………….164 6.7. Nach Norden zu Rendile und Wanderobo……………………………..175 6.8. Forschungsreise als Kriegszug…………………………………………..185 6.9. Scheitern einer Forschungsexpedition…………………………………195 7. Resume…………………………………………………………………………205 8. Bibliographie………………………………………………………………....210 9. Anhang 9.1. Inhaltsangabe/Abstract……………………………………………………228 -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer From Lake Nyassa to Philadelphia Citation for published version: Dritsas, L 2005, 'From Lake Nyassa to Philadelphia: a geography of the Zambesi Expedition, 1858–64 ' British Journal for the History of Science, vol 38, no. 1, pp. 35-52. DOI: 10.1017/S0007087404006454 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0007087404006454 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: British Journal for the History of Science Publisher Rights Statement: ©Dritsas, L. (2005). From Lake Nyassa to Philadelphia: a geography of the Zambesi Expedition, 1858–64 . British Journal for the History of Science, 38(1), 35-52doi: 10.1017/S0007087404006454 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. -

PART II PERSONAL PAPERS and ORGANIZATIONAL RECORDS Allen, Paul Hamilton, 1911-1963 Collection 1 RG 4/1/5/15 Photographs, 1937-1959 (1.0 Linear Feet)

PART II PERSONAL PAPERS AND ORGANIZATIONAL RECORDS Allen, Paul Hamilton, 1911-1963 Collection 1 RG 4/1/5/15 Photographs, 1937-1959 (1.0 linear feet) Paul Allen was a botanist and plantsman of the American tropics. He was student assistant to C. W. Dodge, the Garden's mycologist, and collector for the Missouri Botanical Garden expedition to Panama in 1934. As manager of the Garden's tropical research station in Balboa, Panama, from 1936 to 1939, he actively col- lected plants for the Flora of Panama. He was the representative of the Garden in Central America, 1940-43, and was recruited after the War to write treatments for the Flora of Panama. The photos consist of 1125 negatives and contact prints of plant taxa, including habitat photos, herbarium specimens, and close-ups arranged in alphabetical order by genus and species. A handwritten inventory by the donor in the collection file lists each item including 19 rolls of film of plant communities in El Salvador, Costa Rica, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama. The collection contains 203 color slides of plants in Panama, other parts of Central America, and North Borneo. Also included are black and white snapshots of Panama, 1937-1944, and specimen photos presented to the Garden's herbarium. Allen's field books and other papers that may give further identification are housed at the Hunt Institute of Botanical Documentation. Copies of certain field notebooks and specimen books are in the herbarium curator correspondence of Robert Woodson, (Collection 1, RG 4/1/1/3). Gift, 1983-1990. ARRANGEMENT: 1) Photographs of Central American plants, no date; 2) Slides, 1947-1959; 3) Black and White photos, 1937-44. -

The Correspondence of Peter Macowan (1830 - 1909) and George William Clinton (1807 - 1885)

The Correspondence of Peter MacOwan (1830 - 1909) and George William Clinton (1807 - 1885) Res Botanica Missouri Botanical Garden December 13, 2015 Edited by P. M. Eckel, P.O. Box 299, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, Missouri, 63166-0299; email: mailto:[email protected] Portrait of Peter MacOwan from the Clinton Correspondence, Buffalo Museum of Science, Buffalo, New York, USA. Another portrait is noted by Sayre (1975), published by Marloth (1913). The proper citation of this electronic publication is: "Eckel, P. M., ed. 2015. Correspondence of Peter MacOwan(1830–1909) and G. W. Clinton (1807–1885). 60 pp. Res Botanica, Missouri Botanical Garden Web site.” 2 Acknowledgements I thank the following sequence of research librarians of the Buffalo Museum of Science during the decade the correspondence was transcribed: Lisa Seivert, who, with her volunteers, constructed the excellent original digital index and catalogue to these letters, her successors Rachael Brew, David Hemmingway, and Kathy Leacock. I thank John Grehan, Director of Science and Collections, Buffalo Museum of Science, Buffalo, New York, for his generous assistance in permitting me continued access to the Museum's collections. Angela Todd and Robert Kiger of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie-Melon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, provided the illustration of George Clinton that matches a transcribed letter by Michael Shuck Bebb, used with permission. Terry Hedderson, Keeper, Bolus Herbarium, Capetown, South Africa, provided valuable references to the botany of South Africa and provided an inspirational base for the production of these letters when he visited St. Louis a few years ago. Richard Zander has provided invaluable technical assistance with computer issues, especially presentation on the Web site, manuscript review, data search, and moral support. -

Dritsas, Lawrence. from Lake Nyassa to Philadelphia: a Geography of the Zambesi Expedition, 1858-64

Dritsas, Lawrence. From Lake Nyassa to Philadelphia: a geography of the Zambesi Expedition, 1858-64. British Journal for the History of Science. 38(1): 35–52, March 2005. DOI: 10.1017/S0007087404006454 This is a PDF of an article accepted for inclusion in the British Journal for the History of Science , published by Cambridge University Press following peer review. The publisher-authenticated version is available online at http://journals.cambridge.org/ . This online paper must be cited in line with the usual academic conventions. This article is protected under full copyright law. You may download it for your own personal use only. Edinburgh Research Archive: www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk Contact: [email protected] BJHS 38(1): 35–52, March 2005. f British Society for the History of Science DOI: 10.1017/S0007087404006454 From Lake Nyassa to Philadelphia: a geography of the Zambesi Expedition, 1858–64 LAWRENCE DRITSAS* Abstract. This paper is about collecting, travel and the geographies of science. At one level it examines the circumstances that led to Isaac Lea’s description in Philadelphia of six freshwater mussel shells of the family Unionidae, originally collected by John Kirk during David Livingstone’s Zambesi Expedition, 1858–64. At another level it is about how travel is necess- ary in the making of scientific knowledge. Following these shells from south-eastern Africa to Philadelphia via London elucidates the journeys necessary for Kirk and Lea’s scientific work to progress and illustrates that the production of what was held to be malacological knowledge occurred through collaborative endeavours that required the travel of the specimens them- selves. -

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 7Th Edition

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names th 7 Edition ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori Published by All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be The Internation Seed Testing Association (ISTA) reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted Zürichstr. 50, CH-8303 Bassersdorf, Switzerland in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior ©2020 International Seed Testing Association (ISTA) permission in writing from ISTA. ISBN 978-3-906549-77-4 ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 1st Edition 1966 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Prof P. A. Linehan 2nd Edition 1983 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. H. Pirson 3rd Edition 1988 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. W. A. Brandenburg 4th Edition 2001 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 5th Edition 2007 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 6th Edition 2013 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 7th Edition 2019 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori 2 7th Edition ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names Content Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Symbols and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... -

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration Along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History That Refl Ects National Trends

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History that Refl ects National Trends DOUG BENSON Honorary Research Associate, National Herbarium of New South Wales, Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Sydney NSW 2000, AUSTRALIA. [email protected] Published on 10 April 2019 at https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/LIN/index Benson, D. (2019). Two centuries of botanical exploration along the Botanists Way, northern Blue Mountains,N.S.W: a regional botanical history that refl ects national trends. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 141, 1-24. The Botanists Way is a promotional concept developed by the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden at Mt Tomah for interpretation displays associated with the adjacent Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (GBMWHA). It is based on 19th century botanical exploration of areas between Kurrajong and Bell, northwest of Sydney, generally associated with Bells Line of Road, and focussed particularly on the botanists George Caley and Allan Cunningham and their connections with Mt Tomah. Based on a broader assessment of the area’s botanical history, the concept is here expanded to cover the route from Richmond to Lithgow (about 80 km) including both Bells Line of Road and Chifl ey Road, and extending north to the Newnes Plateau. The historical attraction of botanists and collectors to the area is explored chronologically from 1804 up to the present, and themes suitable for visitor education are recognised. Though the Botanists Way is focused on a relatively limited geographic area, the general sequence of scientifi c activities described - initial exploratory collecting; 19th century Gentlemen Naturalists (and lady illustrators); learned societies and publications; 20th century publicly-supported research institutions and the beginnings of ecology, and since the 1960s, professional conservation research and management - were also happening nationally elsewhere. -

A History of Nairobi, Capital of Kenya

....IJ .. Kenya Information Dept. Nairobi, Showing the Legislative Council Building TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Chapter I. Pre-colonial Background • • • • • • • • • • 4 II. The Nairobi Area. • • • • • • • • • • • • • 29 III. Nairobi from 1896-1919 •• • • • • • • • • • 50 IV. Interwar Nairobi: 1920-1939. • • • • • • • 74 V. War Time and Postwar Nairobi: 1940-1963 •• 110 VI. Independent Nairobi: 1964-1966 • • • • • • 144 Appendix • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 168 Bibliographical Note • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 179 Bibliography • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 182 iii PREFACE Urbanization is the touchstone of civilization, the dividing mark between raw independence and refined inter dependence. In an urbanized world, countries are apt to be judged according to their degree of urbanization. A glance at the map shows that the under-developed countries are also, by and large, rural. Cities have long existed in Africa, of course. From the ancient trade and cultural centers of Carthage and Alexandria to the mediaeval sultanates of East Africa, urban life has long existed in some degree or another. Yet none of these cities changed significantly the rural character of the African hinterland. Today the city needs to be more than the occasional market place, the seat of political authority, and a haven for the literati. It remains these of course, but it is much more. It must be the industrial and economic wellspring of a large area, perhaps of a nation. The city has become the concomitant of industrialization and industrialization the concomitant 1 2 of the revolution of rising expectations. African cities today are largely the products of colonial enterprise but are equally the measure of their country's progress. The city is witness everywhere to the acute personal, familial, and social upheavals of society in the process of urbanization. -

THE LINNEAN SOCIETY of LONDON Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W 1V OLQ

THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W 1V OLQ President Secretaries council Prof. M. F. Claridge BOTANICAL ‘The Officers and Dr C. J. Humphrirs Miss C. E. Appleby President-Elect Dr J. A. Beardmore Pro[ J. G. Hawkes ZOOLOGICAL Dr P. E. Brandham Prof. J. Green Mr F. H. Brightman Vice-Presidents Dr D. F. Cutler Dr D. Edwards EDITORIAL Dr D. Edwards Prof. J. Green Prof. J. D. Pye Dr Y. X. Erzinclioglu Prof. J. G. Hawkes Mrs P. D. Fry Dr K. A. Joysey Executive Secretary Dr D. J. Calloway Dr J. C. Marsden Dr P. A. Henderson Treasurer Dr G. McC. Reid Dr R. W. J. Keay Librarian Dr P. R. Richards Miss G. Douglas Dr V. R. Southgate Membership Maria J. Polius Meetings Marquita Baird THE LINNEAN Newsletter and Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London Edited by B. G. Gardiner .. Editorial ..............11 Society News .............1 Correspondence .............6 Clift, Darwin, Owen and the Dinosauria.. (2) .....8 Proceedings of the Society ..........15 Library ...............37 Editorial This issue of The Linnean includes a second article tracing the impact that Sir Richard Owen had on vertebrate palaeontology and comparative anatomy. It was written to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the naming of the Dinosauria which falls this Summer. Later in the year (August 30) the Royal Mail will be issuing a commemorative set of dinosaur stamps. The concern expressed in our last issue at the low level of funding for taxonomic research at the Natural History Museum has been answered by a standard letter from the Minister for Arts (see Correspondence). -

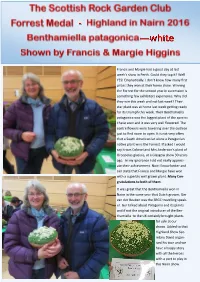

Francis and Margie Had a Good Day at Last Week's Show in Perth. Could They Top It? Well YES! Emphatically. I Don't Know

Francis and Margie had a good day at last week’s show in Perth. Could they top it? Well YES! Emphatically. I don’t know how many first prizes they won at their home show. Winning the Forrest for the second year in succession is something few exhibitors experience. Why did they win this week and not last week? Their star plant was at home last week getting ready for its triumph this week. Their Benthamiella patagonica was the biggest plant of the species I have seen and it was very well flowered. The centre flowers were towering over the cushion just to find room to open. It is not very often that a South American let alone a Patagonian native plant wins the Forrest. If asked I would say it was Colonel and Mrs Anderson’s plant of Oreopolus glaciais, at a Glasgow show 30 years ago. In my ignorance I did not really appreci- ate their achievement. Now I know better and can state that Francis and Margie have won with a superbly well grown plant. Many Con- gratulations to both of them. It was great that the Benthamiella won in Nairn in the same year that Dutch grower, Ger van der Beuken was the SRGC travelling speak- er. Ger talked about Patagonia and its plants and if not the original introducer of the Ben- thamiella to the UK certainly brought plants for sale at our shows. Added to that Highland Show Sec- retary David organ- ised his tour and we have a happy story with all the heroes with a part to play in this Nairn show. -

Asa Gray's Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830S-1860S)

Finding Patterns in Nature: Asa Gray's Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830s-1860s) The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Hung, Kuang-Chi. 2013. Finding Patterns in Nature: Asa Gray's Citation Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830s-1860s). Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Accessed April 17, 2018 4:20:57 PM EDT Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11181178 This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH Terms of Use repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA (Article begins on next page) Finding Patterns in Nature: Asa Gray’s Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830s-1860s) A dissertation presented by Kuang-Chi Hung to The Department of the History of Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts July 2013 © 2013–Kuang-Chi Hung All rights reserved Dissertation Advisor: Janet E. Browne Kuang-Chi Hung Finding Patterns in Nature: Asa Gray’s Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830s-1860s) Abstract It is well known that American botanist Asa Gray’s 1859 paper on the floristic similarities between Japan and the United States was among the earliest applications of Charles Darwin's evolutionary theory in plant geography. Commonly known as Gray’s “disjunction thesis,” Gray's diagnosis of that previously inexplicable pattern not only provoked his famous debate with Louis Agassiz but also secured his role as the foremost advocate of Darwin and Darwinism in the United States.