Sir Joseph Hooker's Collections at the Royal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disciplinary Culture

Disciplinary Culture: Artillery, Sound, and Science in Woolwich, 1800–1850 Simon Werrett This article explores connections between science, music, and the military in London in the first decades of the nineteenth century.1 Rather than look for applications of music or sound in war, it considers some techniques common to these fields, exemplified in practices involving the pendulum as an instrument of regulation. The article begins by exploring the rise of military music in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and then compares elements of this musical culture to scientific transformations during 1 For broad relations between music and science in this period, see: Myles Jackson, Harmonious Triads: Physicians, Musicians, and Instrument Makers in Nineteenth-Century Germany (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006); Alexandra Hui, The Psychophysical Ear: Musical Experiments, Experimental Sounds, 1840–1910 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012); Emily I. Dolan and John Tresch, “‘A Sublime Invasion’: Meyerbeer, Balzac, and the Opera Machine,” Opera Quarterly 27 (2011), 4–31; Emily Thompson, The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900–1933 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004). On science and war in the Napoleonic period, see for example: Simon Werrett, “William Congreve’s Rational Rockets,” Notes & Records of the Royal Society 63 (2009), 35–56; on sound as a weapon, Roland Wittje, “The Electrical Imagination: Sound Analogies, Equivalent Circuits, and the Rise of Electroacoustics, 1863–1939,” Osiris 28 (2013), 40–63, here 55; Cyrus C. M. Mody, “Conversions: Sound and Sight, Military and Civilian,” in The Oxford Handbook of Sound Studies, eds. Trevor Pinch and Karin Bijsterveld (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. -

Natural Selection: Charles Darwin & Alfred Russel Wallace

Search | Glossary | Home << previous | next > > Natural Selection: Charles Darwin & Alfred Russel Wallace The genius of Darwin (left), the way in which he suddenly turned all of biology upside down in 1859 with the publication of the Origin of Species , can sometimes give the misleading impression that the theory of evolution sprang from his forehead fully formed without any precedent in scientific history. But as earlier chapters in this history have shown, the raw material for Darwin's theory had been known for decades. Geologists and paleontologists had made a compelling case that life had been on Earth for a long time, that it had changed over that time, and that many species had become extinct. At the same time, embryologists and other naturalists studying living animals in the early 1800s had discovered, sometimes unwittingly, much of the A visit to the Galapagos Islands in 1835 helped Darwin best evidence for Darwin's formulate his ideas on natural selection. He found theory. several species of finch adapted to different environmental niches. The finches also differed in beak shape, food source, and how food was captured. Pre-Darwinian ideas about evolution It was Darwin's genius both to show how all this evidence favored the evolution of species from a common ancestor and to offer a plausible mechanism by which life might evolve. Lamarck and others had promoted evolutionary theories, but in order to explain just how life changed, they depended on speculation. Typically, they claimed that evolution was guided by some long-term trend. Lamarck, for example, thought that life strove over time to rise from simple single-celled forms to complex ones. -

The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886

The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886 Sascha Nolden, Simon Nathan & Esme Mildenhall Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H November 2013 Published by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand Inc, 2013 Information on the Society and its publications is given at www.gsnz.org.nz © Copyright Simon Nathan & Sascha Nolden, 2013 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H ISBN 978-1-877480-29-4 ISSN 2230-4495 (Online) ISSN 2230-4487 (Print) We gratefully acknowledge financial assistance from the Brian Mason Scientific and Technical Trust which has provided financial support for this project. This document is available as a PDF file that can be downloaded from the Geoscience Society website at: http://www.gsnz.org.nz/information/misc-series-i-49.html Bibliographic Reference Nolden, S.; Nathan, S.; Mildenhall, E. 2013: The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886. Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H. 219 pages. The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886 CONTENTS Introduction 3 The Sumner Cave controversy Sources of the Haast-Hooker correspondence Transcription and presentation of the letters Acknowledgements References Calendar of Letters 8 Transcriptions of the Haast-Hooker letters 12 Appendix 1: Undated letter (fragment), ca 1867 208 Appendix 2: Obituary for Sir Julius von Haast 209 Appendix 3: Biographical register of names mentioned in the correspondence 213 Figures Figure 1: Photographs -

Bon Voyage? 250 Years Exploring the Natural World SHNH Summer

Bon Voyage? 250 Years Exploring the Natural World SHNH summer meeting and AGM in association with the BOC World Museum Liverpool Thursday 14th and Friday 15th June 2018 Abstracts Thursday 14th June Jordan Goodman, Department of Science and Technology Studies, University College London In the Wake of Cook? Joseph Banks and His ‘Favorite Projects’ James Cook’s three Pacific voyages spanned the years from 1768 to 1780. These were the first British voyages of exploration in which natural history collecting formed an integral part. Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander were responsible for the collection on the first voyage, HMS Endeavour, between 1768 and 1771; Johann and Georg Forster, collected on the second voyage, HMS Resolution, between 1772 and 1775; and David Nelson continued the tradition on the third voyage, HMS Resolution, from 1776 to 1780. Though Cook’s first voyage brought Banks immense fame, it was the third voyage that initiated a new kind of botanical collecting which he practised for the rest of his life. He called it his ‘Favorite Project’, and it consisted of supplying the royal garden at Kew with living plants from across the globe, to make it the finest botanical collection in the world. Banks appointed David Nelson, a Kew gardener, to collect on Cook’s third voyage. Not only would the King’s garden benefit from a supply of exotic living plants, but the gardeners Banks sent out to collect them would also learn how best to keep the plants alive at sea, for long periods of time and through many different climatic conditions. -

“A Valuable Monument of Mathematical Genius”\Thanksmark T1: the Ladies' Diary (1704–1840)

Historia Mathematica 36 (2009) 10–47 www.elsevier.com/locate/yhmat “A valuable monument of mathematical genius” ✩: The Ladies’ Diary (1704–1840) Joe Albree ∗, Scott H. Brown Auburn University, Montgomery, USA Available online 24 December 2008 Abstract Our purpose is to view the mathematical contribution of The Ladies’ Diary as a whole. We shall range from the state of mathe- matics in England at the beginning of the 18th century to the transformations of the mathematics that was published in The Diary over 134 years, including the leading role The Ladies’ Diary played in the early development of British mathematics periodicals, to finally an account of how progress in mathematics and its journals began to overtake The Diary in Victorian Britain. © 2008 Published by Elsevier Inc. Résumé Notre but est de voir la contribution mathématique du Journal de Lady en masse. Nous varierons de l’état de mathématiques en Angleterre au début du dix-huitième siècle aux transformations des mathématiques qui a été publié dans le Journal plus de 134 ans, en incluant le principal rôle le Journal de Lady joué dans le premier développement de périodiques de mathématiques britanniques, à finalement un compte de comment le progrès dans les mathématiques et ses journaux a commencé à dépasser le Journal dans l’Homme de l’époque victorienne la Grande-Bretagne. © 2008 Published by Elsevier Inc. Keywords: 18th century; 19th century; Other institutions and academies; Bibliographic studies 1. Introduction Arithmetical Questions are as entertaining and delightful as any other Subject whatever, they are no other than Enigmas, to be solved by Numbers; . -

List of Honorary Fellows

LIST OF HONORARY FELLOWS. 847 LIST OF HONORARY FELLOWS .110 AT MARCH 1897. His Royal Highness The PRINCE OF WALES. FOREIGNERS (LIMITED TO THIRTY-SIX BY LAW X.). Elected. 495 1897 Alexander Agassiz, Cambridge (Mass.). 1897 E.-H. Amagat, Paris. 1889 Marcellin Pierre Eugene Berthelot, Paris. 1895 Ludwig Boltzmann, Vienna. 1864 Rohert Wilhelm Bunsen, Heidelberg. 1897 Stanislao Cannizzaro, Rome, 1883 Luigi Cremona, Rome. 1877 Carl Gegenbaur, Heidelberg, 1888 Ernst Haeckel, Jena. 1883 Julius Hann, Vienna. 1884 Charles Hermite, Paris. 1879 Jules Janssen, Paris, 1864 Alhert von Kblliker, Wilrzhurg. 1864 Rudolph Leuckart, Leipzig, 1897 Gabriel Lippmann, Paris. 1895 fileuthere-6lie-Nicolas Mascart, Paris. 1888 Demetrius Ivanovich Mendel6ef, St Petersburg. 1895 Carl Menger, Vienna. 1886 Alphonse Milne-Edwards Paris. 1864 Theodore Mommsen, Berlin. 1897 Fridtjof Nansen, Christiania. 1881 Simon Newcomb, Washington. 1895 Max von Pettenkofer, Munich. 1895 Jules Henri Poincare, Paris. 1889 Georg Hermann Quincke, Heidelberg. 1886 Alphonse Renard, Ghent. 1897 Ferdinand von Ricbthofen, Berlin. 1897 Henry A. Rowland, Baltimore. 1897 Giovanni V. Schiaparelli, Milan, 1881 Johannes Iapetus Smith Steenstrup, Copenhagen. 1878 Otto Wilhelm Strove, St Petersburg. 1886 Tobias Robert Thaten, Upsala. 1874 Otto Torell, Lund. 1868 Rudolph Yirchow, Berlin. 1892 Gustav Wiedemann, Leipzig. 1897 Ferdinand Zirkel, Leipzig. Total, 36. 848 LIST OF HONORARY FELLOWS. BRITISH SUBJECTS (LIMITED TO TWENTY BY LAW x.). Elected. 1889 Sir Robert Stawell Ball, Kt., LL.D., F.R.S., M.R.I. A., Lowndean, Professor of Astronomy in the University of Cambridge, Cambridge 1897 The Very Rev. John Caird, D.D., LL.D., Principal of the Uni- versity of Glasgow, Glasgow. 1892 Colonel Alexander Ross Clarke, C.B., R.E., F.R.S., Redhill, Surrey 1897 George Howard Darwin, M.A., LL.D., F.R.S., Plumian Professor of Astronomy in the University of Cambridge, Cambridge. -

The Correspondence of Peter Macowan (1830 - 1909) and George William Clinton (1807 - 1885)

The Correspondence of Peter MacOwan (1830 - 1909) and George William Clinton (1807 - 1885) Res Botanica Missouri Botanical Garden December 13, 2015 Edited by P. M. Eckel, P.O. Box 299, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, Missouri, 63166-0299; email: mailto:[email protected] Portrait of Peter MacOwan from the Clinton Correspondence, Buffalo Museum of Science, Buffalo, New York, USA. Another portrait is noted by Sayre (1975), published by Marloth (1913). The proper citation of this electronic publication is: "Eckel, P. M., ed. 2015. Correspondence of Peter MacOwan(1830–1909) and G. W. Clinton (1807–1885). 60 pp. Res Botanica, Missouri Botanical Garden Web site.” 2 Acknowledgements I thank the following sequence of research librarians of the Buffalo Museum of Science during the decade the correspondence was transcribed: Lisa Seivert, who, with her volunteers, constructed the excellent original digital index and catalogue to these letters, her successors Rachael Brew, David Hemmingway, and Kathy Leacock. I thank John Grehan, Director of Science and Collections, Buffalo Museum of Science, Buffalo, New York, for his generous assistance in permitting me continued access to the Museum's collections. Angela Todd and Robert Kiger of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie-Melon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, provided the illustration of George Clinton that matches a transcribed letter by Michael Shuck Bebb, used with permission. Terry Hedderson, Keeper, Bolus Herbarium, Capetown, South Africa, provided valuable references to the botany of South Africa and provided an inspirational base for the production of these letters when he visited St. Louis a few years ago. Richard Zander has provided invaluable technical assistance with computer issues, especially presentation on the Web site, manuscript review, data search, and moral support. -

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 7Th Edition

ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names th 7 Edition ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori Published by All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be The Internation Seed Testing Association (ISTA) reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted Zürichstr. 50, CH-8303 Bassersdorf, Switzerland in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior ©2020 International Seed Testing Association (ISTA) permission in writing from ISTA. ISBN 978-3-906549-77-4 ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names 1st Edition 1966 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Prof P. A. Linehan 2nd Edition 1983 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. H. Pirson 3rd Edition 1988 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. W. A. Brandenburg 4th Edition 2001 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 5th Edition 2007 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 6th Edition 2013 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 7th Edition 2019 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori 2 7th Edition ISTA List of Stabilized Plant Names Content Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Symbols and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... -

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration Along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History That Refl Ects National Trends

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History that Refl ects National Trends DOUG BENSON Honorary Research Associate, National Herbarium of New South Wales, Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Sydney NSW 2000, AUSTRALIA. [email protected] Published on 10 April 2019 at https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/LIN/index Benson, D. (2019). Two centuries of botanical exploration along the Botanists Way, northern Blue Mountains,N.S.W: a regional botanical history that refl ects national trends. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 141, 1-24. The Botanists Way is a promotional concept developed by the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden at Mt Tomah for interpretation displays associated with the adjacent Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (GBMWHA). It is based on 19th century botanical exploration of areas between Kurrajong and Bell, northwest of Sydney, generally associated with Bells Line of Road, and focussed particularly on the botanists George Caley and Allan Cunningham and their connections with Mt Tomah. Based on a broader assessment of the area’s botanical history, the concept is here expanded to cover the route from Richmond to Lithgow (about 80 km) including both Bells Line of Road and Chifl ey Road, and extending north to the Newnes Plateau. The historical attraction of botanists and collectors to the area is explored chronologically from 1804 up to the present, and themes suitable for visitor education are recognised. Though the Botanists Way is focused on a relatively limited geographic area, the general sequence of scientifi c activities described - initial exploratory collecting; 19th century Gentlemen Naturalists (and lady illustrators); learned societies and publications; 20th century publicly-supported research institutions and the beginnings of ecology, and since the 1960s, professional conservation research and management - were also happening nationally elsewhere. -

Endrés As an Illustrator

chapter∑ 4 Endrés as an illustrator Franco Pupulin According to the definition provided by Botanical Gardens Conservation International, “the main goal of botanical illustration is not art, but scientific accuracy”. A botanical illustrator must portray a plant with enough precision and detail for it to be recognized and distinguished from another species, and the need for exactness is what fundamentally differentiates botanical illustration from more general flower painting. If, traditionally, the best botanical illustrators try to understand the structure of plants and to communicate that in an aesthetically pleasing manner, combining science and art, this was probably not the concern of Auguste R. Endrés when preparing his orchid illustrations in Costa Rica. He had, however, a remarkable artistic talent, and his activity was influenced by the great tradition of orchid painting. The results of his illustration work not only attain the highest levels of botanical accuracy, but set a new standard in orchid art and science. As we will see, only because his masterful plates were lost among the forgotten materials of Reichenbach’s venomous legacy, was Endrés’ work prevented from having a major influence on the discipline of botanical illustration. The golden age of botanical illustration in Europe Beginning in the 17th century, and more frequently during the Enlightenment of the 18th Century, European artists and scientists undertook major projects for collecting and cataloguing nature in its amazing variety. 1613 saw the publication of the Hortus Eystettensis1 (literally the Garden of Eichstätt), a landmark work in the history of botanical art and one of the greatest botanical sets ever created. -

Joseph Hooker Takes a "Fixed Post": Transmutation And

Joseph Hooker Takes a "Fixed Post": Transmutation and the "Present Unsatisfactory State of Systematic Botany", 1844-1860 Author(s): Richard Bellon Source: Journal of the History of Biology, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Spring, 2006), pp. 1-39 Published by: Springer Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4331989 Accessed: 24-05-2018 19:09 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the History of Biology This content downloaded from 206.253.207.235 on Thu, 24 May 2018 19:09:40 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Journal of the History of Biology (2006) 39: 1-39 ? Springer 2006 DOI 10.007/sI 0739-004-3800-x Joseph Hooker Takes a "Fixed Post": Transmutation and the "Present Unsatisfactory State of Systematic Botany", 18 441860 RICHARD BELLON Lyman Briggs School Michigan State University E-30 Holmes Hall East Lansing, MI 48825 USA E-mail: hellonr(@.~msu.edu Abstract. Joseph Hooker first learned that Charles Darwin believed in the transmuta- tion of species in 1844. For the next 14 years, Hooker remained a "nonconsenter" to Darwin's views, resolving to keep the question of species origin "subservient to Botany instead of Botany to it, as must be the true relation." Hooker placed particular emphasis on the need for any theory of species origin to support the broad taxonomic delimitation of species, a highly contentious issue. -

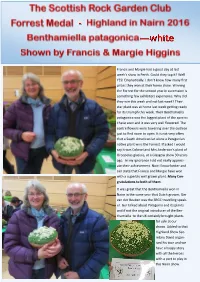

Francis and Margie Had a Good Day at Last Week's Show in Perth. Could They Top It? Well YES! Emphatically. I Don't Know

Francis and Margie had a good day at last week’s show in Perth. Could they top it? Well YES! Emphatically. I don’t know how many first prizes they won at their home show. Winning the Forrest for the second year in succession is something few exhibitors experience. Why did they win this week and not last week? Their star plant was at home last week getting ready for its triumph this week. Their Benthamiella patagonica was the biggest plant of the species I have seen and it was very well flowered. The centre flowers were towering over the cushion just to find room to open. It is not very often that a South American let alone a Patagonian native plant wins the Forrest. If asked I would say it was Colonel and Mrs Anderson’s plant of Oreopolus glaciais, at a Glasgow show 30 years ago. In my ignorance I did not really appreci- ate their achievement. Now I know better and can state that Francis and Margie have won with a superbly well grown plant. Many Con- gratulations to both of them. It was great that the Benthamiella won in Nairn in the same year that Dutch grower, Ger van der Beuken was the SRGC travelling speak- er. Ger talked about Patagonia and its plants and if not the original introducer of the Ben- thamiella to the UK certainly brought plants for sale at our shows. Added to that Highland Show Sec- retary David organ- ised his tour and we have a happy story with all the heroes with a part to play in this Nairn show.