The Beginning of Competitive Banking in Philadelphia, 1782- 1809

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizens Financial Group, Inc

Citizens Financial Group, Inc. 165(d) Resolution Plan Public Summary December 31, 2016 CFG 165(d) Resolution Plan Public Section PUBLIC SECTION Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1. Material Entities............................................................................................................... 3 2. Core Business Lines ....................................................................................................... 3 3. Summary of Financial Information, Capital and Major Funding Sources........................ 7 4. Derivative and Hedging Activities.................................................................................... 10 5. Membership in Material Payment, Clearing and Settlement Systems ............................ 12 6. Foreign Operations ......................................................................................................... 13 7. Material Supervisory Authorities...................................................................................... 13 8. Principal Officers ............................................................................................................. 14 9. Resolution Planning Corporate Governance, Structure and Processes ......................... 14 10. Material Management Information Systems.................................................................. 14 11. High Level Description of Citizens' Resolution Strategy............................................... -

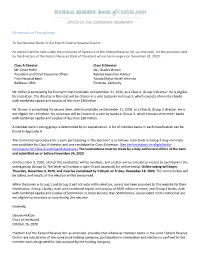

Nomination Procedures

Nomination Procedures To the Member Banks of the Fourth Federal Reserve District: An election will be held under the provisions of Section 4 of the Federal Reserve Act, as amended, for the positions held by the directors of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland whose terms expire on December 31, 2020: Class A Director Class B Director Mr. Dean Miller Mr. Charles Brown President and Chief Executive Officer Retired Executive Advisor First National Bank Toyota Motor North America Bellevue, Ohio Florence, Kentucky Mr. Miller is completing his first term that concludes on December 31, 2020, as a Class A, Group 3 director. He is eligible for reelection. The director in this seat will be chosen in a vote by banks in Group 3, which consists of member banks with combined capital and surplus of less than $30million. Mr. Brown is completing his second term, which concludes on December 31, 2020, as a Class B, Group 3 director. He is not eligible for reelection. His successor will be chosen in a vote by banks in Group 3, which consists of member banks with combined capital and surplus of less than $30 million. A member bank's voting group is determined by its capitalization. A list of member banks in each classification can be found in Appendix A. The nomination procedure for a bank participating in this election* is as follows: Each bank in Group 3 may nominate one candidate for Class A director and one candidate for Class B director. (See the limitations on eligibility for nomination for Class A and Class B directors.) The nominations must be made by a duly authorized officer of the bank and submitted on or before November 24, 2020. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☑ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the FISCAL YEAR ended December 31, 2020 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from ___________________ to ___________________ Commission Registrant; State of Incorporation; I.R.S. Employer File Number Address; and Telephone Number Identification No. 333-21011 FIRSTENERGY CORP 34-1843785 (An Ohio Corporation) 76 South Main Street Akron OH 44308 Telephone (800) 736-3402 SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OF THE ACT: Title of Each Class Trading Symbol Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, $0.10 par value per share FE New York Stock Exchange SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(g) OF THE ACT: None. Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☑ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☑ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Working Paper Series Department of Economics Alfred Lerner College of Business & Economics University of Delaware

Working Paper Series Department of Economics Alfred Lerner College of Business & Economics University of Delaware Working Paper No. 2004-07 The Constitutional Creation of a Common Currency in the U.S. 1748-1811: Monetary Stabilization Versus Merchant Rent Seeking. Farley Grubb FARLEY GRUBB THE CONSTITUTIONAL CREATION OF A COMMON CURRENCY IN THE U.S., 1748-1811: MONETARY STABILIZATION VERSUS MERCHANT RENT SEEKING The value of having a single currency, the optimal size of currency unions, and the cost of forming such unions, is an unresolved debate1. An important aspect of this debate is the empirical success claimed for currency unions such as the United States. The fact that otherwise-sovereign states within the United States are not legally allowed to issue their own currency, thus creating a single cur- rency zone for the whole United States based on the U.S. dollar, is commonly used as an example for emulation and as justification for policy choices, such as the current move toward a European currency union based on the Euro2. The benefits of this constitutionally created U.S. currency union and, by analogy, the benefits for other politically manufactured currency unions are as- sumed to be obvious, namely a reduction in monetary instability and exchange- rate transactions costs within the union thereby stimulating long-run economic growth. These alleged benefits for the U.S., however, are not derived from market evidence, but from simple theoretical assertions and from a historical literature that has taken as fact the rhetoric of the winning side at the U.S. Con- stitutional Convention. Independent of theory and rhetoric, little is known about how and why the U.S. -

A Model of the International Monetary System∗

A MODEL OF THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY SYSTEM∗ EMMANUEL FARHI AND MATTEO MAGGIORI We propose a simple model of the international monetary system. We study the world supply and demand for reserve assets denominated in different curren- cies under a variety of scenarios: a hegemon versus a multipolar world; abundant versus scarce reserve assets; and a gold exchange standard versus a floating rate system. We rationalize the Triffin dilemma, which posits the fundamental insta- bility of the system, as well as the common prediction regarding the natural and beneficial emergence of a multipolar world, the Nurkse warning that a multipolar world is more unstable than a hegemon world, and the Keynesian argument that a scarcity of reserve assets under a gold standard or at the zero lower bound is recessionary. Our analysis is both positive and normative. JEL Codes: D42, E12, E42, E44, F3, F55, G15, G28. I. INTRODUCTION We propose a formal model of the the International Mone- tary System (IMS). We consider the IMS as the collection of three key attributes: (i) the supply of and demand for reserve assets; (ii) the exchange rate regime; and (iii) international monetary in- stitutions. We show how modern theories developed to analyze sovereign debt crises, oligopolistic competition, and Keynesian ∗We thank Pol Antras,` Julien Bengui, Guillermo Calvo, Dick Cooper, Ana Fostel, Jeffry Frieden, Mark Gertler, Gita Gopinath, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Veronica Guerrieri, Guido Lorenzoni, Arnaud Mehl, Brent Neiman, Jaromir Nosal, Maurice Obstfeld, Jonathan Ostry, -

Monetary Policy and the Dollar Peter L. Rousseaua 1. Introduction Twenty

Monetary Policy and the Dollar Peter L. Rousseaua 1. Introduction Twenty-first century Americans take for granted that a dollar is worth a dollar, meaning that a given Federal Reserve note at a point in time carries a fixed purchasing power regardless of who tenders it or where it is tendered. And though one may rightfully say that prices of goods with identical physical characteristics can and do differ across localities and that a dollar may therefore not purchase the same quantities of goods everywhere, an apple in New York is a distinct economic good from an apple in Cleveland. This again just means that a dollar is worth a dollar with no questions asked of its holder. When the United States adopted the dollar as a common currency shortly after the ratification of the Federal Constitution in 1788, it represented the birth of the monetary system that for the most part continues to the present day―a system that eventually led to the dollar’s universal acceptance and rise to its position as the world’s leading currency. With it came a central bank, a mint, the start of modern banking operations and securities markets, and a newly- found confidence among investors in the ability of the young nation to service its financial obligations. The new system and its specie standard represented a marked improvement over the fiat paper money systems that had operated in the British North American colonies prior to their independence in 1776, and an enormous improvement over the rapidly-deteriorating monetary conditions that existed during the during the Revolutionary War (1776-1781) and under the Articles of Confederation (1781-1788). -

The Financial Services Roundtable Insurance Information Institute

05Fs.cover 12/21/04 1:06 PM Page 1 (2,1) 110 WFilliam StreetINANCIAL New York, NY 10038 (212) 669-9200 http//wwwS.iii.org ERVICES Insurance Information FACT Institute The Financial BOOK Services Roundtable 2 0 0 5 05.fm.fs. 12/20/04 1:58 PM Page i T h e FINAN C IAL SERVI C E S FACT B O O K 2 0 0 5 Insurance Information Institute The Financial Services Roundtable 05.fm.fs. 12/20/04 1:58 PM Page ii TO THE READER The Financial Services Fact Book, a partnership of the Insurance Information Institute and The Financial Services Roundtable, has become an indispensable resource for executives, public officials, researchers and others seeking a better understanding of financial services. In this, our fourth edition, we also identify important trends emerging post Gramm- Leach-Bliley that affect financial services as a whole. We have put these together in a sepa- rate chapter. We now see, for example, that more than 50 percent of bank holding companies a re re p o rting income from sales of insurance, mutual funds and annuities, and from invest- ment banking activities. And the number of financial holding companies involved in insur- ance underwriting more than doubled from 2000 to 2003. Early data for 2004 suggest these t rends will continue upward. In addition to these trends, other features that have been added to this edition include: • Percentage of workers with retirement benefits • Remittances (money transfers from immigrants to their families in other countries) • Information technology spending in the insurance industry • New charts on finance companies and e-commerce and more details on bank loans. -

John Dickinson Papers Dickinson Finding Aid Prepared by Finding Aid Prepared by Holly Mengel

John Dickinson papers Dickinson Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Holly Mengel.. Last updated on September 02, 2020. Library Company of Philadelphia 2010.09.30 John Dickinson papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 8 Related Materials......................................................................................................................................... 10 Controlled Access Headings........................................................................................................................10 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 13 Series I. John Dickinson........................................................................................................................13 Series II. Mary Norris Dickinson..........................................................................................................33 -

Lessons for Eu Integration from Us History

LESSONS FOR EU INTEGRATION FROM US HISTORY Jacob Funk Kirkegaard and Adam S. Posen, editors Report to the European Commission under Tender Reference 2016: ECFIN 004/A Washington, DC January 2018 © 2018 European Commission. All rights reserved. The Peterson Institute for International Economics is a private nonpartisan, nonprofit institution for rigorous, intellectually open, and indepth study and discussion of international economic policy. Its purpose is to identify and analyze important issues to make globalization beneficial and sustainable for the people of the United States and the world, and then to develop and communicate practical new approaches for dealing with them. Its work is funded by a highly diverse group of philanthropic foundations, private corporations, and interested individuals, as well as income on its capital fund. About 35 percent of the Institute’s resources in its latest fiscal year were provided by contributors from outside the United States. Funders are not given the right to final review of a publication prior to its release. A list of all financial supporters is posted at https://piie.com/sites/default/files/supporters.pdf. Table of Contents 1 Realistic European Integration in Light of US Economic History 2 Jacob Funk Kirkegaard and Adam S. Posen 2 A More Perfect (Fiscal) Union: US Experience in Establishing a 16 Continent‐Sized Fiscal Union and Its Key Elements Most Relevant to the Euro Area Jacob Funk Kirkegaard 3 Federalizing a Central Bank: A Comparative Study of the Early 108 Years of the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank Jérémie Cohen‐Setton and Shahin Vallée 4 The Long Road to a US Banking Union: Lessons for Europe 143 Anna Gelpern and Nicolas Véron 5 The Synchronization of US Regional Business Cycles: Evidence 185 from Retail Sales, 1919–62 Jérémie Cohen‐Setton and Egor Gornostay 1 Realistic European Integration in Light of US Economic History Jacob Funk Kirkegaard and Adam S. -

Central Bank Activism Duke Law Journal, Vol

Central Bank Activism Duke Law Journal, Vol. 71: __ (forthcoming) Christina Parajon Skinner † ABSTRACT—Today, the Federal Reserve is at a critical juncture in its evolution. Unlike any prior period in U.S. history, the Fed now faces increasing demands to expand its policy objectives to tackle a wide range of social and political problems—including climate change, income and racial inequality, and foreign and small business aid. This Article develops a framework for recognizing, and identifying the problems with, “central bank activism.” It refers to central bank activism as situations in which immediate public policy problems push central banks to aggrandize their power beyond the text and purpose of their legal mandates, which Congress has established. To illustrate, the Article provides in-depth exploration of both contemporary and historic episodes of central bank activism, thus clarifying the indicia of central bank activism and drawing out the lessons that past episodes should teach us going forward. The Article urges that, while activism may be expedient in the near term, there are long-term social costs. Activism undermines the legitimacy of central bank authority, erodes its political independence, and ultimately renders a weaker central bank. In the end, the Article issues an urgent call to resist the allure of activism. And it places front and center the need for vibrant public discourse on the role of a central bank in American political and economic life today. © 2021 Christina Parajon Skinner. Draft 2021-05-27 20:46. † Assistant Professor, The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. This article benefited from feedback provided by workshop or conference participants at The Wharton School, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York . -

The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1998 The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage William Brenner University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Brenner, William, "The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage" (1998). Theses (Historic Preservation). 488. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/488 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Brenner, William (1998). The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/488 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Brenner, William (1998). The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/488 UNIVERSITY^ PENN5YLV^NIA. UBKARIE5 The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage William Brenner A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 1998 George E. 'Thomas, Advisor Eric Wm. Allison, Reader Lecturer in Historic Preservation President, Historic District ouncil University of Pennsylvania New York City iuatg) Group Chair Frank G. -

Stephen Girard and the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793. – by Howard Anton – ©All Rights Reserved

Click Here to Return to Home Page and Main Menu Stephen Girard and the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793. – by Howard Anton – ©All Rights Reserved The year was 1793. The British were invading the French Pestilence colony of Saint-Domingue (roughly present day Haiti), and Hot, dry winds forever blowing, French landowners, some of their slaves, and many free Dead men to the grave-yards going: people of color were fleeing to the port cities of the United Constant hearses, States, including Philadelphia. Unwittingly, they brought Funeral verses; with them a secret passenger – Aedes aegypti, the mosquito Oh! what plagues – there is no knowing! that carries and transmits the deadly yellow fever virus. Priests retreating from their pulpits! The insects thrived in the standing pools of water, the rain Some in hot, and some in cold fits buckets, and the marshy conditions of Philadelphia, and an In bad temper, epidemic was born. Off they scamper, The epidemic spread with lightening speed, the death Leaving us – unhappy culprits! count mounted, and panicked citizens fled the city in Doctors raving and disputing, droves. President Washington and other national leaders Death’s pale army still recruiting departed for safer environs, the post office closed, all but What a pother one newspaper shut down, citizens stayed locked in their One with t’other! houses, and a pall of gloom descended on the city. The best Some a-writing, some a-shooting. doctors of the time seemed helpless to stem the rising tide Nature’s poisons here collected of deaths. Water, earth, and air infected Among those who stayed was the 43-year old merchant O, what a pity, Stephen Girard.