The Suffolk Bank and the Panic of 1837: How a Private Bank Acted As a Lender-Of-Last-Resort*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calculated for the Use of the State Of

3i'R 317.3M31 H41 A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of IVIassachusetts, Boston http://www.archive.org/details/pocketalmanackfo1839amer MASSACHUSETTS REGISTER, AND mmwo states ©alrntiar, 1839. ALSO CITY OFFICERS IN BOSTON, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY JAMES LORING, 13 2 Washington Street. ECLIPSES IN 1839. 1. The first will be a great and total eclipse, on Friday March 15th, at 9h. 28m. morning, but by reason of the moon's south latitude, her shadow will not touch any part of North America. The course of the general eclipse will be from southwest to north- east, from the Pacific Ocean a little west of Chili to the Arabian Gulf and southeastern part of the Mediterranean Sea. The termination of this grand and sublime phenomenon will probably be witnessed from the summit of some of those stupendous monuments of ancient industry and folly, the vast and lofty pyramids on the banks of the Nile in lower Egypt. The principal cities and places that will be to- tally shadowed in this eclipse, are Valparaiso, Mendoza, Cordova, Assumption, St. Salvador and Pernambuco, in South America, and Sierra Leone, Teemboo, Tombucto and Fezzan, in Africa. At each of these places the duration of total darkness will be from one to six minutes, and several of the planets and fixed stars will probably be visible. 2. The other will also be a grand and beautiful eclipse, on Satur- day, September 7th, at 5h. 35m. evening, but on account of the Mnon's low latitude, and happening so late in the afternoon, no part of it will be visible in North America. -

Citizens Financial Group, Inc

Citizens Financial Group, Inc. 165(d) Resolution Plan Public Summary December 31, 2016 CFG 165(d) Resolution Plan Public Section PUBLIC SECTION Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1. Material Entities............................................................................................................... 3 2. Core Business Lines ....................................................................................................... 3 3. Summary of Financial Information, Capital and Major Funding Sources........................ 7 4. Derivative and Hedging Activities.................................................................................... 10 5. Membership in Material Payment, Clearing and Settlement Systems ............................ 12 6. Foreign Operations ......................................................................................................... 13 7. Material Supervisory Authorities...................................................................................... 13 8. Principal Officers ............................................................................................................. 14 9. Resolution Planning Corporate Governance, Structure and Processes ......................... 14 10. Material Management Information Systems.................................................................. 14 11. High Level Description of Citizens' Resolution Strategy............................................... -

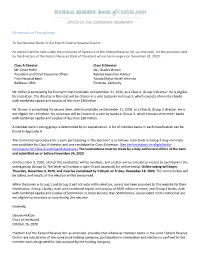

Nomination Procedures

Nomination Procedures To the Member Banks of the Fourth Federal Reserve District: An election will be held under the provisions of Section 4 of the Federal Reserve Act, as amended, for the positions held by the directors of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland whose terms expire on December 31, 2020: Class A Director Class B Director Mr. Dean Miller Mr. Charles Brown President and Chief Executive Officer Retired Executive Advisor First National Bank Toyota Motor North America Bellevue, Ohio Florence, Kentucky Mr. Miller is completing his first term that concludes on December 31, 2020, as a Class A, Group 3 director. He is eligible for reelection. The director in this seat will be chosen in a vote by banks in Group 3, which consists of member banks with combined capital and surplus of less than $30million. Mr. Brown is completing his second term, which concludes on December 31, 2020, as a Class B, Group 3 director. He is not eligible for reelection. His successor will be chosen in a vote by banks in Group 3, which consists of member banks with combined capital and surplus of less than $30 million. A member bank's voting group is determined by its capitalization. A list of member banks in each classification can be found in Appendix A. The nomination procedure for a bank participating in this election* is as follows: Each bank in Group 3 may nominate one candidate for Class A director and one candidate for Class B director. (See the limitations on eligibility for nomination for Class A and Class B directors.) The nominations must be made by a duly authorized officer of the bank and submitted on or before November 24, 2020. -

Universita' Degli Studi Di Padova

UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI PADOVA DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE ECONOMICHE ED AZIENDALI “M.FANNO” CORSO DI LAUREA MAGISTRALE / SPECIALISTICA IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION TESI DI LAUREA “The American banking system before the FED” RELATORE: CH.MO PROF. GIANFRANCO TUSSET LAUREANDO: CARLO RUBBO MATRICOLA N. 1121213 ANNO ACCADEMICO 2016 – 2017 ANNO ACCADEMICO 2016 – 2017 Il candidato dichiara che il presente lavoro è originale e non è già stato sottoposto, in tutto o in parte, per il conseguimento di un titolo accademico in altre Università italiane o straniere. Il candidato dichiara altresì che tutti i materiali utilizzati durante la preparazione dell’elaborato sono stati indicati nel testo e nella sezione “Riferimenti bibliografici” e che le eventuali citazioni testuali sono individuabili attraverso l’esplicito richiamo alla pubblicazione originale. Firma dello studente _________________ INDEX INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 2 CHAPTER ONE ........................................................... 4 THE INDEPENDENCE WAR AND THE BANK OF NORTH AMERICA .... 5 THE FIRST BANK OF THE UNITED STATES 1791 – 1811 ........................... 8 THE SECOND BANK OF THE UNITED STATES 1816-1833 ....................... 13 THE DECENTRALIZED BANKING SYSTEM 1837 – 1863 .......................... 17 CIVIL WAR FINANCING AND THE NATIONAL BANKING SYSTEM ... 23 PANICS OF THE END OF THE CENTURY AND ROAD TO THE FED .... 27 CHAPTER TWO ........................................................ 39 THE ROLE OF THE U.S. SUPREME COURT ................................................ 40 THE SUFFOLK SYSTEM: A “FREE MARKET CENTRAL BANK” .......... 45 DO THE U.S. NEED A CENTRALIZED BANKING SYSTEM? ................... 49 FINAL REFLECTIONS ............................................ 64 BIBLIOGRAPHY ....................................................... 69 1 INTRODUCTION The history of the American banking system is not well-known but it is very important, since it has shaped the current financial market of the country. The U.S. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☑ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the FISCAL YEAR ended December 31, 2020 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from ___________________ to ___________________ Commission Registrant; State of Incorporation; I.R.S. Employer File Number Address; and Telephone Number Identification No. 333-21011 FIRSTENERGY CORP 34-1843785 (An Ohio Corporation) 76 South Main Street Akron OH 44308 Telephone (800) 736-3402 SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OF THE ACT: Title of Each Class Trading Symbol Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, $0.10 par value per share FE New York Stock Exchange SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(g) OF THE ACT: None. Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☑ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☑ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed

Economic Quarterly— Volume 100, Number 2— Second Quarter 2014— Pages 159–181 The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed Robert L. Hetzel ilton Friedman (1982, 103) wrote: “In our book on U.S. mon- etary history, Anna Schwartz and I found it possible to use M one sentence to describe the central principle followed by the Federal Reserve System from the time it began operations in 1914 to 1952. That principle, to quote from our book, is: ‘Ifthe ‘money market’ is properly managed so as to avoid the unproductive use of credit and to assure the availability of credit for productive use, then the money stock will take care of itself.’” For Friedman, the reference to “the money stock”was synonymous with “the price level.”1 How did American monetary experience and debate in the 19th century give rise to these “real bills” views as a guide to Fed policy in the pre-World War II period? As distilled in the real bills doctrine, the founders of the Fed under- stood the Federal Reserve System as a decentralized system of reserve depositories that would allow the expansion and contraction of currency and credit based on discounting member-bank paper that originated out of productive activity. By discounting these “real bills,”the short- term loans that …nanced trade and goods in the process of production, policymakers ful…lled their responsibilities as they understood them. That is, they would provide the reserves required to accommodate the “legitimate,” nonspeculative, demands for credit.2 In so doing, they The author acknowledges helpful comments from Huberto Ennis, Motoo Haruta, Gary Richardson, Robert Sharp, Kurt Schuler, Ellis Tallman, and Alexander Wolman. -

A Model of the International Monetary System∗

A MODEL OF THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY SYSTEM∗ EMMANUEL FARHI AND MATTEO MAGGIORI We propose a simple model of the international monetary system. We study the world supply and demand for reserve assets denominated in different curren- cies under a variety of scenarios: a hegemon versus a multipolar world; abundant versus scarce reserve assets; and a gold exchange standard versus a floating rate system. We rationalize the Triffin dilemma, which posits the fundamental insta- bility of the system, as well as the common prediction regarding the natural and beneficial emergence of a multipolar world, the Nurkse warning that a multipolar world is more unstable than a hegemon world, and the Keynesian argument that a scarcity of reserve assets under a gold standard or at the zero lower bound is recessionary. Our analysis is both positive and normative. JEL Codes: D42, E12, E42, E44, F3, F55, G15, G28. I. INTRODUCTION We propose a formal model of the the International Mone- tary System (IMS). We consider the IMS as the collection of three key attributes: (i) the supply of and demand for reserve assets; (ii) the exchange rate regime; and (iii) international monetary in- stitutions. We show how modern theories developed to analyze sovereign debt crises, oligopolistic competition, and Keynesian ∗We thank Pol Antras,` Julien Bengui, Guillermo Calvo, Dick Cooper, Ana Fostel, Jeffry Frieden, Mark Gertler, Gita Gopinath, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Veronica Guerrieri, Guido Lorenzoni, Arnaud Mehl, Brent Neiman, Jaromir Nosal, Maurice Obstfeld, Jonathan Ostry, -

Financial Panics and Scandals

Wintonbury Risk Management Investment Strategy Discussions www.wintonbury.com Financial Panics, Scandals and Failures And Major Events 1. 1343: the Peruzzi Bank of Florence fails after Edward III of England defaults. 2. 1621-1622: Ferdinand II of the Holy Roman Empire debases coinage during the Thirty Years War 3. 1634-1637: Tulip bulb bubble and crash in Holland 4. 1711-1720: South Sea Bubble 5. 1716-1720: Mississippi Bubble, John Law 6. 1754-1763: French & Indian War (European Seven Years War) 7. 1763: North Europe Panic after the Seven Years War 8. 1764: British Currency Act of 1764 9. 1765-1769: Post war depression, with farm and business foreclosures in the colonies 10. 1775-1783: Revolutionary War 11. 1785-1787: Post Revolutionary War Depression, Shays Rebellion over farm foreclosures. 12. Bank of the United States, 1791-1811, Alexander Hamilton 13. 1792: William Duer Panic in New York 14. 1794: Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania (Gallatin mediates) 15. British currency crisis of 1797, suspension of gold payments 16. 1808: Napoleon Overthrows Spanish Monarchy; Shipping Marques 17. 1813: Danish State Default 18. 1813: Suffolk Banking System established in Boston and eventually all of New England to clear bank notes for members at par. 19. Second Bank of the United States, 1816-1836, Nicholas Biddle 20. Panic of 1819, Agricultural Prices, Bank Currency, and Western Lands 21. 1821: British restoration of gold payments 22. Republic of Poyais fraud, London & Paris, 1820-1826, Gregor MacGregor. 23. British Banking Crisis, 1825-1826, failed Latin American investments, etc., six London banks including Henry Thornton’s Bank and sixty country banks failed. -

Economic Quarterly, Second Quarter 2014, Vol. 100, No. 2

Economic Quarterly— Volume 100, Number 2— Second Quarter 2014— Pages 87–111 Flows To and From Working Part Time for Economic Reasons and the Labor Market Aggregates During and After the 2007{09 Recession Maria E.Canon,Marianna Kudlyak, Guannan Luo, and Marisa Reed hile the unemployment rate is one of the most cited eco- nomic indicators, economists and policymakers also exam- W ine a wide array of other indicators to gauge the health of the U.S. labor market. One such indicator is the U-6 index, an extended measure of the unemployment rate published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). In addition to unemployed workers, the U-6 index in- cludes individuals who are working part time for economic reasons and individuals who are out of the labor force but are marginally attached to the labor market. Individuals are classi…ed as working part time for economic reasons (henceforth, PTER) if they work fewer than 35 hours per week, want to work full time, and cite “slack business conditions”1 Canon is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Luo is an assistant professor at the City University of Hong Kong. Kudlyak is an economist and Reed is a research associate at the Federal Re- serve Bank of Richmond. The authors are very grateful to Alex Wolman, Felipe Schwartzman, Christian Matthes, and Peter Debbaut for useful com- ments and suggestions. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not re‡ect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. -

John Dickinson Papers Dickinson Finding Aid Prepared by Finding Aid Prepared by Holly Mengel

John Dickinson papers Dickinson Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Holly Mengel.. Last updated on September 02, 2020. Library Company of Philadelphia 2010.09.30 John Dickinson papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 8 Related Materials......................................................................................................................................... 10 Controlled Access Headings........................................................................................................................10 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 13 Series I. John Dickinson........................................................................................................................13 Series II. Mary Norris Dickinson..........................................................................................................33 -

Lessons for Eu Integration from Us History

LESSONS FOR EU INTEGRATION FROM US HISTORY Jacob Funk Kirkegaard and Adam S. Posen, editors Report to the European Commission under Tender Reference 2016: ECFIN 004/A Washington, DC January 2018 © 2018 European Commission. All rights reserved. The Peterson Institute for International Economics is a private nonpartisan, nonprofit institution for rigorous, intellectually open, and indepth study and discussion of international economic policy. Its purpose is to identify and analyze important issues to make globalization beneficial and sustainable for the people of the United States and the world, and then to develop and communicate practical new approaches for dealing with them. Its work is funded by a highly diverse group of philanthropic foundations, private corporations, and interested individuals, as well as income on its capital fund. About 35 percent of the Institute’s resources in its latest fiscal year were provided by contributors from outside the United States. Funders are not given the right to final review of a publication prior to its release. A list of all financial supporters is posted at https://piie.com/sites/default/files/supporters.pdf. Table of Contents 1 Realistic European Integration in Light of US Economic History 2 Jacob Funk Kirkegaard and Adam S. Posen 2 A More Perfect (Fiscal) Union: US Experience in Establishing a 16 Continent‐Sized Fiscal Union and Its Key Elements Most Relevant to the Euro Area Jacob Funk Kirkegaard 3 Federalizing a Central Bank: A Comparative Study of the Early 108 Years of the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank Jérémie Cohen‐Setton and Shahin Vallée 4 The Long Road to a US Banking Union: Lessons for Europe 143 Anna Gelpern and Nicolas Véron 5 The Synchronization of US Regional Business Cycles: Evidence 185 from Retail Sales, 1919–62 Jérémie Cohen‐Setton and Egor Gornostay 1 Realistic European Integration in Light of US Economic History Jacob Funk Kirkegaard and Adam S. -

New York and the Politics of Central Banks, 1781 to the Federal Reserve Act

New York and the Politics of Central Banks, 1781 to the Federal Reserve Act Jon R. Moen and Ellis W. Tallman Working Paper 2003-42 December 2003 Working Paper Series Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Working Paper 2003-42 December 2003 New York and the Politics of Central Banks, 1781 to the Federal Reserve Act Jon R. Moen, University of Mississippi Ellis W. Tallman, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Abstract: The paper provides a brief history of central banking institutions in the United States. Specifically, the authors highlight the role of New York banking interests in the legislations affecting the creation or expiration of central banking institutions. In our previous research we have detected that New York City banking entities usually exert substantial influence on legislation, greater than their large proportion of United States’ banking resources. The authors describe how this influence affected the success or failure of central banking movements in the United States, and the authors use this evidence to support their arguments regarding the influence of New York City bankers on the legislative efforts that culminated in the creation of the Federal Reserve System. The paper argues that successful central banking movements in the United States owed much to the influence of New York City banking interests. JEL classification: N21, N41 Key words: financial crisis, central bank, banking legislation The authors gratefully acknowledge William Roberds for helpful comments and conversations. The views expressed here are the authors’ and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System. Any remaining errors are the authors’ responsibility.