A Model of the International Monetary System∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizens Financial Group, Inc

Citizens Financial Group, Inc. 165(d) Resolution Plan Public Summary December 31, 2016 CFG 165(d) Resolution Plan Public Section PUBLIC SECTION Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1. Material Entities............................................................................................................... 3 2. Core Business Lines ....................................................................................................... 3 3. Summary of Financial Information, Capital and Major Funding Sources........................ 7 4. Derivative and Hedging Activities.................................................................................... 10 5. Membership in Material Payment, Clearing and Settlement Systems ............................ 12 6. Foreign Operations ......................................................................................................... 13 7. Material Supervisory Authorities...................................................................................... 13 8. Principal Officers ............................................................................................................. 14 9. Resolution Planning Corporate Governance, Structure and Processes ......................... 14 10. Material Management Information Systems.................................................................. 14 11. High Level Description of Citizens' Resolution Strategy............................................... -

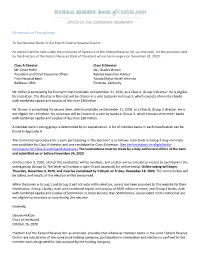

Nomination Procedures

Nomination Procedures To the Member Banks of the Fourth Federal Reserve District: An election will be held under the provisions of Section 4 of the Federal Reserve Act, as amended, for the positions held by the directors of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland whose terms expire on December 31, 2020: Class A Director Class B Director Mr. Dean Miller Mr. Charles Brown President and Chief Executive Officer Retired Executive Advisor First National Bank Toyota Motor North America Bellevue, Ohio Florence, Kentucky Mr. Miller is completing his first term that concludes on December 31, 2020, as a Class A, Group 3 director. He is eligible for reelection. The director in this seat will be chosen in a vote by banks in Group 3, which consists of member banks with combined capital and surplus of less than $30million. Mr. Brown is completing his second term, which concludes on December 31, 2020, as a Class B, Group 3 director. He is not eligible for reelection. His successor will be chosen in a vote by banks in Group 3, which consists of member banks with combined capital and surplus of less than $30 million. A member bank's voting group is determined by its capitalization. A list of member banks in each classification can be found in Appendix A. The nomination procedure for a bank participating in this election* is as follows: Each bank in Group 3 may nominate one candidate for Class A director and one candidate for Class B director. (See the limitations on eligibility for nomination for Class A and Class B directors.) The nominations must be made by a duly authorized officer of the bank and submitted on or before November 24, 2020. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☑ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the FISCAL YEAR ended December 31, 2020 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from ___________________ to ___________________ Commission Registrant; State of Incorporation; I.R.S. Employer File Number Address; and Telephone Number Identification No. 333-21011 FIRSTENERGY CORP 34-1843785 (An Ohio Corporation) 76 South Main Street Akron OH 44308 Telephone (800) 736-3402 SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OF THE ACT: Title of Each Class Trading Symbol Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, $0.10 par value per share FE New York Stock Exchange SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(g) OF THE ACT: None. Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☑ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☑ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

John Dickinson Papers Dickinson Finding Aid Prepared by Finding Aid Prepared by Holly Mengel

John Dickinson papers Dickinson Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Holly Mengel.. Last updated on September 02, 2020. Library Company of Philadelphia 2010.09.30 John Dickinson papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 8 Related Materials......................................................................................................................................... 10 Controlled Access Headings........................................................................................................................10 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 13 Series I. John Dickinson........................................................................................................................13 Series II. Mary Norris Dickinson..........................................................................................................33 -

Lessons for Eu Integration from Us History

LESSONS FOR EU INTEGRATION FROM US HISTORY Jacob Funk Kirkegaard and Adam S. Posen, editors Report to the European Commission under Tender Reference 2016: ECFIN 004/A Washington, DC January 2018 © 2018 European Commission. All rights reserved. The Peterson Institute for International Economics is a private nonpartisan, nonprofit institution for rigorous, intellectually open, and indepth study and discussion of international economic policy. Its purpose is to identify and analyze important issues to make globalization beneficial and sustainable for the people of the United States and the world, and then to develop and communicate practical new approaches for dealing with them. Its work is funded by a highly diverse group of philanthropic foundations, private corporations, and interested individuals, as well as income on its capital fund. About 35 percent of the Institute’s resources in its latest fiscal year were provided by contributors from outside the United States. Funders are not given the right to final review of a publication prior to its release. A list of all financial supporters is posted at https://piie.com/sites/default/files/supporters.pdf. Table of Contents 1 Realistic European Integration in Light of US Economic History 2 Jacob Funk Kirkegaard and Adam S. Posen 2 A More Perfect (Fiscal) Union: US Experience in Establishing a 16 Continent‐Sized Fiscal Union and Its Key Elements Most Relevant to the Euro Area Jacob Funk Kirkegaard 3 Federalizing a Central Bank: A Comparative Study of the Early 108 Years of the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank Jérémie Cohen‐Setton and Shahin Vallée 4 The Long Road to a US Banking Union: Lessons for Europe 143 Anna Gelpern and Nicolas Véron 5 The Synchronization of US Regional Business Cycles: Evidence 185 from Retail Sales, 1919–62 Jérémie Cohen‐Setton and Egor Gornostay 1 Realistic European Integration in Light of US Economic History Jacob Funk Kirkegaard and Adam S. -

New York and the Politics of Central Banks, 1781 to the Federal Reserve Act

New York and the Politics of Central Banks, 1781 to the Federal Reserve Act Jon R. Moen and Ellis W. Tallman Working Paper 2003-42 December 2003 Working Paper Series Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Working Paper 2003-42 December 2003 New York and the Politics of Central Banks, 1781 to the Federal Reserve Act Jon R. Moen, University of Mississippi Ellis W. Tallman, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Abstract: The paper provides a brief history of central banking institutions in the United States. Specifically, the authors highlight the role of New York banking interests in the legislations affecting the creation or expiration of central banking institutions. In our previous research we have detected that New York City banking entities usually exert substantial influence on legislation, greater than their large proportion of United States’ banking resources. The authors describe how this influence affected the success or failure of central banking movements in the United States, and the authors use this evidence to support their arguments regarding the influence of New York City bankers on the legislative efforts that culminated in the creation of the Federal Reserve System. The paper argues that successful central banking movements in the United States owed much to the influence of New York City banking interests. JEL classification: N21, N41 Key words: financial crisis, central bank, banking legislation The authors gratefully acknowledge William Roberds for helpful comments and conversations. The views expressed here are the authors’ and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System. Any remaining errors are the authors’ responsibility. -

The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1998 The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage William Brenner University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Brenner, William, "The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage" (1998). Theses (Historic Preservation). 488. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/488 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Brenner, William (1998). The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/488 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Brenner, William (1998). The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/488 UNIVERSITY^ PENN5YLV^NIA. UBKARIE5 The Preservation and Adaptation of a Financial Architectural Heritage William Brenner A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 1998 George E. 'Thomas, Advisor Eric Wm. Allison, Reader Lecturer in Historic Preservation President, Historic District ouncil University of Pennsylvania New York City iuatg) Group Chair Frank G. -

The Suffolk Bank and the Panic of 1837: How a Private Bank Acted As a Lender-Of-Last-Resort*

The Suffolk Bank and the Panic of 1837: How a Private Bank Acted as a Lender-of-Last-Resort* Arthur J. Rolnick Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Bruce D. Smith University of Texas at Austin and Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Warren E. Weber Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and University of Minnesota Abstract Before the establishment of federal deposit insurance, the U.S. experienced periodic banking panics, during which banks suspended specie payments and reduced lending. There was often a corresponding economic slowdown. The Panic of 1837 is considered one of the worst banking panics, and it coincided with a slowdown that lasted for almost five years. The economic disruption was not uniform across the country, however. The slowdown in New England was substantially less severe than elsewhere. Here we suggest that the Suffolk Bank, a private bank, was one reason for New England’s relative success. We argue that the Suffolk Bank’s provision of note-clearing and lender-of-last-resort services (via the Suffolk Banking System) lessened the effects of the Panic of 1837 in New England relative to the rest of the country, where no bank provided such services. * The authors thank the Baker Library, Harvard Business School for the materials provided from its Suffolk Bank Collection. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. 484 Arthur J. Rolnick, Bruce D. Smith, and Warren E. Weber Before the establishment of federal deposit insurance in 1935, the U.S. -

Safe Banking: Finance and Democracy Adam J

Safe Banking: Finance and Democracy Adam J. Levitin† Banking is based on two fundamentally irreconcilable functions: safekeeping of deposits and relending of deposits. Safekeeping is meant to be a risk-free func- tion, but using deposits to fund loans inevitably poses risk to deposits, thereby un- dermining the safekeeping function. The expensive, inefficient, and unreliable ap- paratus of bank regulation is an attempt to square the circle between safekeeping and lending: government liquidity and deposit insurance facilities, capital and re- serve requirements, investment restrictions, and supervisory examinations are all aimed at keeping the risks of the lending function in check so as to ensure the safe- ty of deposits. This Article argues for splitting the lending function from the safekeeping function in both traditional- and shadow-banking markets through what it terms “Pure Reserve Banking.” In a Pure Reserve Banking regime, “safe banks” would offer safekeeping and payment services, and nothing else. Loans would be a func- tion solely of capital markets, which would operate without government facilitation of shadow-banking deposit substitutes. Historically, a separation between deposits and lending was not possible, but it is now feasible with today’s deep and efficient capital markets, which already provide the funding for much of the borrowing in the economy. Splitting the lending function from the safekeeping function would protect both the money supply from the market and the market from the money supply. It would enable the government to end its massive support of both formal-banking markets and shadow-banking markets and would thereby remove the moral haz- ard that encourages asset bubbles through overlending. -

Open Before Christmas

CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK » TODAY’S ISSUE U DAILY BRIEFING, A2 • TRIBUTES, A7 • WORLD & BUSINESS, B5 • CLASSIFIEDS, B6 • PUZZLES & TV, C3 BASICS OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP HOOP DREAMS GOLDEN GLOBES 50% Canfi eld grad shares her recipe A look at top boys teams ‘La La Land’ leads the list OFF LOCAL | A3 SPORTS | B1 VALLEY LIFE | C1 VOUCHERS. DETAILS, A2 FOR DAILY & BREAKING NEWS LOCALLY OWNED SINCE 1869 TUESDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2016 U 75¢ YSU MUM ON WHICH PLAYERS OR SUBSTANCE INVOLVED three of the players office has “never discussed any quarterfi nal matchup against Wof- AT LEAST 4 PENGUINS TO MISS FCS PLAYOFF SEMIFINAL facing suspension suspensions or potential suspen- ford on Saturday. By CHARLES GROVE Vindicator at least four players will typically see signif- sions regarding any program.” According to the NCAA’s website, [email protected] be suspended from playing this icant playing time After his weekly radio show stimulants, anabolic agents, di- YOUNGSTOWN Saturday after testing positive for for the Penguins. Monday, Pelini would not confi rm uretics and other masking agents, Youngstown State University will an unidentifi ed substance. Two of the players any suspensions. “I don’t comment street drugs, peptide hormones be without at least four football YSU’s weekly news conference are on defense and on that,” he said. and analogues, anti-estrogens and one on offense. At least a dozen Penguins were players for its FCS national semi- will be at 11:30 a.m. today, where Pelini beta-2 agonists are all classes of fi nal game against Eastern Wash- head coach Bo Pelini is expected YSU Athletic Di- tested for banned substances im- drugs that are banned. -

Library Company of Philadelphia Mca MSS 013 BANK of COLUMBIA

Library Company of Philadelphia McA MSS 013 BANK OF COLUMBIA RECORDS 1794‐1828 1.04 linear feet, 3 boxes Series I. Correspondence (1794‐1828) Series II. Documents (1794‐1822) December 2005 McA MSS 013 2 Descriptive Summary Repository Library Company of Philadelphia 1314 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107‐5698 Call Number McA MSS 013 Creator Bank of Columbia (Georgetown, Washington, D.C.) Title Bank of Columbia Records Inclusive Dates 1794‐1828 Quantity 1.04 linear feet (3 boxes) Language of Materials Materials are in English and French. Abstract The Bank of Columbia Records has correspondence and legal and financial papers that document the history of the bank and its depositors. The collection holds letters, predominantly single letters, from many prominent citizens of Georgetown and Washington in the early nineteenth century, as well as from Treasury Department officials and officers of the Bank of the United States. Administrative Information Restrictions to Access The collection is open to researchers. It is on deposit at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and should be accessed through the Society’s reading room at 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA. Visit their website, http://www.hsp.org/, for reading room hours. Acquisition Information Gift of John A. McAllister; forms part of the McAllister Collection. Processing Information The Bank of Columbia Records were formerly filed within the large and chronologically‐arranged McAllister Manuscript Collection; the papers were reunited, arranged, and described as a single collection in 2005, under grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the William Penn Foundation. The collection was processed Edith Mulhern, a University of Pennsylvania Summer Research Intern, and Sandra Markham. -

Bank of Pennsylvania”

A look back in History : The Friendly Sons of St. Patrick - Philadelphia Joseph P. Heenan February 16, 2018 The Philadelphia Friendly Sons of St. Patrick and the “Bank of Pennsylvania” From the Record Books of The Philadelphia Friendly Sons of St. Patrick “ In the year 1780 a transaction took place in Philadelphia, almost unparalleled in the history of nations and patriotism, which casts a luster not only on the individuals who were the authors of it, but on the whole community to which they belonged. “At the time alluded to, when every thing depended on a vigorous prosecution of the war, when the American army was in imminent danger of being compelled to yield to famine, a far more dangerous enemy then the British, when the urgent expostulations of the commander-in-chief, and the strenuous recommendations of Congress, had utterly failed to arouse a just sense of the danger of the crisis, the genuine love of country, and most noble self-sacrifices of some individuals in Philadelphia, supplied the place of the slumbering patriotism of the country, and saved her cause from most disgraceful ruin. “ In this great emergency was conceived and promptly carried into operation, “ the plan of the Bank of Pennsylvania, established for supplying the army of the United States with provisions for two months” “On the 17th June, 1780, the following paper reported, which deserves to rank as a supplement to the Declaration of Independence, was signed by ninety three individuals and firms: “Whereas, in the present situation of public affairs in the United