AP® EUROPEAN HISTORY 2008 SCORING GUIDELINES (Form B)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Its Beginning and Aftermath with a Main Focus on Austria

Journal of Research and Opinion Received 10 June 2020 | Accepted 21 June 2020 | Published Online 25 June 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15520/jro.v7i6.68 JRO 7 (6), 2738−2748 (2020) ISSN (O) 2589-9341 | (P) 2589-9058 IF:2.1 RESEARCH ARTICLE “The Great War”– Its beginning and aftermath with a main focus on Austria ∗ Rainer Feldbacher 1Associate Professor at the School Abstract of History, Capital Normal Many factors played a crucial role in the start of a conflict that the world University, Beijing, China, 100089 had seen as “a war to end all wars”, that started after the assassination of the crown prince in Sarajevo. Initially a European war, soon nations worldwide got involved. With the end of the World War and the beginning of the collapse of the Habsburg Empire, the “Republic of German-Austria” was proclaimed on November 12th, 1918, after the treaty of Saint-Germain 10 September 1919 officially as “First Republic of Austria“. The circumstances opened the door to National Socialism and the much crueler Second World War. Keywords: Austria-Hungary, World War, Habsburg, Fourteen Points, Peace Treaty of Versailles 1 INTRODUCTION – AUSTRIA´S ROLE IN and in most cases having led to Austria´s misfortune, EUROPE and mainly its disastrous way into the First World War.In the 16th century, the Habsburgs became the absburg, the rulers of the Austrian Empire largest Western European Empire since Rome, ini- whose name originated from the building of Hthe Habsburg Castle in Switzerland, built at tially ruling huge regions of that continent. Soon a the Aar, the largest tributary of the High Rhine river, political division between the Spanish and Austrian had been the dynasty with a long history. -

The Unification of Italy and Germany

EUROPEAN HISTORY Unit 10 The Unification of Italy and Germany Form 4 Unit 10.1 - The Unification of Italy Revolution in Naples, 1848 Map of Italy before unification. Revolution in Rome, 1848 Flag of the Kingdom of Italy, 1861-1946 1. The Early Phase of the Italian Risorgimento, 1815-1848 The settlements reached in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna had restored Austrian domination over the Italian peninsula but had left Italy completely fragmented in a number of small states. The strongest and most progressive Italian state was the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in north-western Italy. At the Congress of Vienna this state had received the lands of the former Republic of Genoa. This acquisition helped Sardinia-Piedmont expand her merchant fleet and trade centred in the port of Genoa. There were three major obstacles to unity at the time of the Congress of Vienna: The Austrians occupied Lombardy and Venetia in Northern Italy. The Papal States controlled Central Italy. The other Italian states had maintained their independence: the Kingdom of Sardinia, also called Piedmont-Sardinia, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (ruler by the Bourbon dynasty) and the Duchies of Tuscany, Parma and Modena (ruled by relatives of the Austrian Habsburgs). During the 1820s the Carbonari secret society tried to organize revolts in Palermo and Naples but with very little success, mainly because the Carbonari did not have the support of the peasants. Then came Giuseppe Mazzini, a patriotic writer who set up a national revolutionary movement known as Young Italy (1831). Mazzini was in favour of a united republic. -

The Unification of Italy

New Dorp High School Social Studies Department AP Global Mr. Hubbs & Mrs. Zoleo The Unification of Italy While nationalism destroyed empires, it also built nations. Italy was one of the countries to form from the territories of the crumbling empires. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Austria ruled the Italian provinces of Venetia and Lombardy in the north, and several small states. In the south, the Spanish Bourbon family ruled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Nevertheless, between 1815 and 1848, increasing numbers of Italians were no longer content to live under foreign rulers. Amid growing discontent, two leaders appeared—one was idealistic, the other practical. They had different personalities and pursued different goals. But each contributed to the Unification of Italy. The Movement for Unity Begins In 1832, an idealistic 26-year-old Italian named Guiseppe Mazzini organized a nationalist group called, Young Italy. Similarly, youth were the leaders and custodians of the nineteenth century nationalist movements. The Napoleonic Wars were lead principally by younger men. Napoleon was 35 years of age when crowned Emperor. As nationalism spread across Europe the pattern continued. People over 40 were excluded from Mazzini's organization. During the violent year of 1848, revolts broke out in eight states on the Italian Peninsula. Mazzini briefly headed a republican government in Rome. He believed that nation-states were the best hope for social justice, democracy, and peace in Europe. However, the 1848 rebellions failed in Italy as they did elsewhere in Europe. The foreign rulers of the Italian states drove Mazzini and other nationalist leaders into exile. -

Mcq Drill for Practice—Test Yourself (Answer Key at the Last)

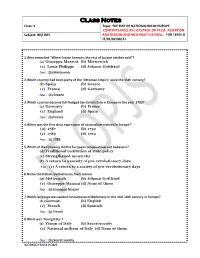

Class Notes Class: X Topic: THE RISE OF NATIONALISM IN EUROPE CONTENTS-MCQ ,FILL UPS,TRUE OR FALSE, ASSERTION Subject: HISTORY AND REASON AND MCQ PRACTICE DRILL… FOR TERM-I/ JT/01/02/08/21 1.Who remarked “When France Sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold”? (a) Giuseppe Mazzini (b) Metternich (c) Louis Philippe (d) Johann Gottfried Ans : (b) Metternich 2.Which country had been party of the ‘Ottoman Empire’ since the 15th century? (b) Spain (b) Greece (c) France (d) Germany Ans : (b) Greece 3.Which country became full-fledged territorial state in Europe in the year 1789? (c) Germany (b) France (c) England (d) Spain Ans : (b) France 4.When was the first clear expression of nationalism noticed in Europe? (a) 1787 (b) 1759 (c) 1789 (d) 1769 Ans : (c) 1789 5.Which of the following did the European conservatives not believe in? (d) Traditional institution of state policy (e) Strengthened monarchy (f) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days Ans : (c) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days 6.Name the Italian revolutionary from Genoa. (g) Metternich (b) Johann Gottfried (c) Giuseppe Mazzini (d) None of these Ans : (c) Giuseppe Mazzini 7.Which language was spoken for purposes of diplomacy in the mid 18th century in Europe? (h) German (b) English (c) French (d) Spanish Ans : (c) French 8.What was ‘Young Italy’ ? (i) Vision of Italy (b) Secret society (c) National anthem of Italy (d) None of these Ans : (b) Secret society WORKED FROM HOME 9.Treaty of Constantinople recognised .......... as an independent nation. -

By Filippo Sabetti Mcgill University the MAKING of ITALY AS AN

THE MAKING OF ITALY AS AN EXPERIMENT IN CONSTITUTIONAL CHOICE by Filippo Sabetti McGill University THE MAKING OF ITALY AS AN EXPERIMENT IN CONSTITUTIONAL CHOICE In his reflections on the history of European state-making, Charles Tilly notes that the victory of unitary principles of organiza- tion has obscured the fact, that federal principles of organization were alternative design criteria in The Formation of National States in West- ern Europe.. Centralized commonwealths emerged from the midst of autonomous, uncoordinated and lesser political structures. Tilly further reminds us that "(n)othing could be more detrimental to an understanding of this whole process than the old liberal conception of European history as the gradual creation and extension of political rights .... Far from promoting (representative) institutions, early state-makers 2 struggled against them." The unification of Italy in the nineteenth century was also a victory of centralized principles of organization but Italian state- making or Risorgimento differs from earlier European state-making in at least three respects. First, the prospects of a single political regime for the entire Italian peninsula and islands generated considerable debate about what model of government was best suited to a population that had for more than thirteen hundred years lived under separate and diverse political regimes. The system of government that emerged was the product of a conscious choice among alternative possibilities con- sidered in the formulation of the basic rules that applied to the organi- zation and conduct of Italian governance. Second, federal principles of organization were such a part of the Italian political tradition that the victory of unitary principles of organization in the making of Italy 2 failed to obscure or eclipse them completely. -

5 How Did Nationalism Lead to a United Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815

#5 How did nationalism lead to a united Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815 • Italy had been divided up • Controlled by ruling families of Austria, France & Spain • Secretive group of revolutionaries formed in S. Italy – inspired by French Rev. 1848 • Nationalistic feelings were intensifying– throughout the 8 Italian city-states • Revolts were led by Giuseppe Mazzini – returned from exile • Leader of the “Young Italy” movement – dedicated to securing “for Italy Unity, Independence & Liberty” These Revolts Failed • Looked to Kingdom of Sardinia to rule a unified Italy – agreed they would rather have a unified Italy with a monarch than a lot of foreign powers ruling over separate states • “Risorgimento” Count Cavour & King Victor Emmanuel II • Wanted to unify Italy – make Piedmont- Sardinia the model for unification • Began public works, building projects, political reform • Next step -- get Austria out of the Italian Peninsula • Outbreak of Crimean War -- France & Britain on one side, Russia on the other • Piedmont-Sardinia saw a chance to earn some respect and make a name for itself • They were victorious and Sardinia was able to attend the peace conference. As a result of this, Piedmont- Sardinia gained the support of Napoleon III. Giuseppe Garibaldi • Italian Nationalist • Invaded S. Italy with his followers, the Red Shirts • Also supported King Victor Emmanuel – Piedmont Sardinia was only nation capable of defeating Austria • Aided by Sardinia – Cavour gave firearms to Garibaldi • Guerrilla warfare (hit & run tactics) Unified Italy • Constitutional monarchy was established – Under King Victor Emmanuel • Rome – new capital • Pope went into “exile” Garibaldi And Victor Emmanuel "Right Leg in the Boot at Last" Problems of Unification • Inexperience in self- government • Tradition of regional independence • Large part of population was illiterate • Lots of debt • Had to build an infrastructure • Severe economic & cultural divisions • (S – poor, N – more industrialized) • Centralized state, but weak Independence • Lots of people left for the U.S. -

Unification of Italy 1792 to 1925 French Revolutionary Wars to Mussolini

UNIFICATION OF ITALY 1792 TO 1925 FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY WARS TO MUSSOLINI ERA SUMMARY – UNIFICATION OF ITALY Divided Italy—From the Age of Charlemagne to the 19th century, Italy was divided into northern, central and, southern kingdoms. Northern Italy was composed of independent duchies and city-states that were part of the Holy Roman Empire; the Papal States of central Italy were ruled by the Pope; and southern Italy had been ruled as an independent Kingdom since the Norman conquest of 1059. The language, culture, and government of each region developed independently so the idea of a united Italy did not gain popularity until the 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars wreaked havoc on the traditional order. Italian Unification, also known as "Risorgimento", refers to the period between 1848 and 1870 during which all the kingdoms on the Italian Peninsula were united under a single ruler. The most well-known character associated with the unification of Italy is Garibaldi, an Italian hero who fought dozens of battles for Italy and overthrew the kingdom of Sicily with a small band of patriots, but this romantic story obscures a much more complicated history. The real masterminds of Italian unity were not revolutionaries, but a group of ministers from the kingdom of Sardinia who managed to bring about an Italian political union governed by ITALY BEFORE UNIFICATION, 1792 B.C. themselves. Military expeditions played an important role in the creation of a United Italy, but so did secret societies, bribery, back-room agreements, foreign alliances, and financial opportunism. Italy and the French Revolution—The real story of the Unification of Italy began with the French conquest of Italy during the French Revolutionary Wars. -

Enjoy Your Visit!!!

declared war on Austria, in alliance with the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and attacked the weakened Austria in her Italian possessions. embarked to Sicily to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the But Piedmontese Army was defeated by Radetzky; Charles Albert abdicated Bourbons. Garibaldi gathered 1.089 volunteers: they were poorly armed in favor of his son Victor Emmanuel, who signed the peace treaty on 6th with dated muskets and were dressed in a minimalist uniform consisting of August 1849. Austria reoccupied Northern Italy. Sardinia wasn’t able to beat red shirts and grey trousers. On 5th May they seized two steamships, which Austria alone, so it had to look for an alliance with European powers. they renamed Il Piemonte and Il Lombardo, at Quarto, near Genoa. On 11th May they landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily; on 15th they Room 8 defeated Neapolitan troops at Calatafimi, than they conquered Palermo on PALAZZO MORIGGIA the 29th , after three days of violent clashes. Following the victory at Milazzo (29th May) they were able to control all the island. The last battle took MUSEO DEL RISORGIMENTO THE DECADE OF PREPARATION 1849-1859 place on 1st October at Volturno, where twenty-one thousand Garibaldini The Decade of Preparation 1849-1859 (Decennio defeated thirty thousand Bourbons soldiers. The feat was a success: Naples di Preparazione) took place during the last years of and Sicily were annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia by a plebiscite. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY HISTORY LABORATORY Risorgimento, ended in 1861 with the proclamation CIVIC HISTORICAL COLLECTION of the Kingdom of Italy, guided by Vittorio Emanuele Room 13-14 II. -

The German National Attack on the Czech Minority in Vienna, 1897

THE GERMAN NATIONAL ATTACK ON THE CZECH MINORITY IN VIENNA, 1897-1914, AS REFLECTED IN THE SATIRICAL JOURNAL Kikeriki, AND ITS ROLE AS A CENTRIFUGAL FORCE IN THE DISSOLUTION OF AUSTRIA-HUNGARY. Jeffery W. Beglaw B.A. Simon Fraser University 1996 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of History O Jeffery Beglaw Simon Fraser University March 2004 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Jeffery Beglaw DEGREE: Master of Arts, History TITLE: 'The German National Attack on the Czech Minority in Vienna, 1897-1914, as Reflected in the Satirical Journal Kikeriki, and its Role as a Centrifugal Force in the Dissolution of Austria-Hungary.' EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Martin Kitchen Senior Supervisor Nadine Roth Supervisor Jerry Zaslove External Examiner Date Approved: . 11 Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without the author's written permission. -

When the Demos Shapes the Polis - the Use of Referendums in Settling Sovereignty Issues

When the Demos Shapes the Polis - The Use of Referendums in Settling Sovereignty Issues. Gary Sussman, London School of Economics (LSE). Introduction This chapter is a survey of referendums dealing with questions of sovereignty. This unique category of referendum usage is characterized by the participation of the demos in determining the shape of the polis or the nature of its sovereignty. The very first recorded referendums, following the French Revolution, were sovereignty referendums. Though far from transparent and fair, these votes were strongly influenced by notions of self- determination and the idea that title to land could not be changed without the consent of those living on that land. Since then there have been over two hundred and forty sovereignty referendums. In the first part of this chapter I will briefly review referendum usage in general. This international analysis of 1094 referendums excludes the United States of America, where initiatives are extensively used by various states and Switzerland, which conducted 414 votes on the national level from 1866 to 1993. This comparative analysis of trends in referendum usage will provide both a sketch of the geographical distribution of use and a sense of use by issue. In the second section of this chapter I examine the history and origins of the sovereignty referendum and identify broad historical trends in its use. It will be demonstrated there have been several high tides in the use of sovereignty referendums and that these high tides are linked to high tides of nationalism, which have often followed the collapse of empires. Following this historical overview a basic typology of six sub-categories, describing sovereignty referendums will be suggested. -

The Great European Treaties of the Nineteenth Century

JBRART Of 9AN DIEGO OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY EDITED BY SIR AUGUSTUS OAKES, CB. LATELY OF THE FOREIGN OFFICE AND R. B. MOWAT, M.A. FELLOW AND ASSISTANT TUTOR OF CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE, OXFORD WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY SIR H. ERLE RICHARDS K. C.S.I., K.C., B.C.L., M.A. FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE AWD CHICHELE PROFESSOR OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND DIPLOMACY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD ASSOCIATE OF THE INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMEN HOUSE, E.C. 4 LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW LEIPZIG NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE CAPETOWN BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS SHANGHAI HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY Impression of 1930 First edition, 1918 Printed in Great Britain INTRODUCTION IT is now generally accepted that the substantial basis on which International Law rests is the usage and practice of nations. And this makes it of the first importance that the facts from which that usage and practice are to be deduced should be correctly appre- ciated, and in particular that the great treaties which have regulated the status and territorial rights of nations should be studied from the point of view of history and international law. It is the object of this book to present materials for that study in an accessible form. The scope of the book is limited, and wisely limited, to treaties between the nations of Europe, and to treaties between those nations from 1815 onwards. To include all treaties affecting all nations would require volumes nor is it for the many ; necessary, purpose of obtaining a sufficient insight into the history and usage of European States on such matters as those to which these treaties relate, to go further back than the settlement which resulted from the Napoleonic wars. -

Mont Blanc in British Literary Culture 1786 – 1826

Mont Blanc in British Literary Culture 1786 – 1826 Carl Alexander McKeating Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Leeds School of English May 2020 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Carl Alexander McKeating to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Carl Alexander McKeating in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Acknowledgements I am grateful to Frank Parkinson, without whose scholarship in support of Yorkshire-born students I could not have undertaken this study. The Frank Parkinson Scholarship stipulates that parents of the scholar must also be Yorkshire-born. I cannot help thinking that what Parkinson had in mind was the type of social mobility embodied by the journey from my Bradford-born mother, Marie McKeating, who ‘passed the Eleven-Plus’ but was denied entry into a grammar school because she was ‘from a children’s home and likely a trouble- maker’, to her second child in whom she instilled a love of books, debate and analysis. The existence of this thesis is testament to both my mother’s and Frank Parkinson’s generosity and vision. Thank you to David Higgins and Jeremy Davies for their guidance and support. I give considerable thanks to Fiona Beckett and John Whale for their encouragement and expert interventions.