The German National Attack on the Czech Minority in Vienna, 1897

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The South Slav Policies of the Habsburg Monarchy

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Nationalitaetenrecht: The outhS Slav Policies of the Habsburg Monarchy Sean Krummerich University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, and the European History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Krummerich, Sean, "Nationalitaetenrecht: The outhS Slav Policies of the Habsburg Monarchy" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4111 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalitätenrecht: The South Slav Policies of the Habsburg Monarchy by Sean Krummerich A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor, Graydon A. Tunstall, Ph.D. Kees Botterbloem, Ph.D. Giovanna Benadusi, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 6, 2012 Keywords – Austria, Hungary, Serb, Croat, Slovene Copyright © 2012, Sean Krummerich Dedication For all that they have done to inspire me to new heights, I dedicate this work to my wife Amanda, and my son, John Michael. Acknowledgments This study would not have been possible without the guidance and support of a number of people. My thanks go to Graydon Tunstall and Kees Boterbloem, for their assistance in locating sources, and for their helpful feedback which served to strengthen this paper immensely. -

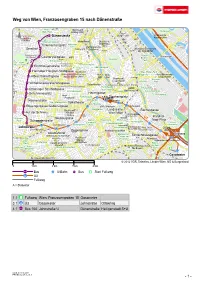

Footpath Description

Weg von Wien, Franzosengraben 15 nach Dänenstraße N Hugo- Bezirksamt Wolf- Park Donaupark Döbling (XIX.) Lorenz- Ignaz- Semmelweis- BUS Dänenstraße Böhler- UKH Feuerwache Kaisermühlen Frauenklinik Fin.- BFI Fundamt BUS Türkenschanzpark Verkehrsamt Bezirksamt amt Brigittenau Türkenschanzplatz Währinger Lagerwiese Park Rettungswache (XX.) Gersthof BUS Finanzamt Brigittenau Pensionsversicherung Brigittenau der Angestellten Orthopädisches Rudolf- BUS Donauinsel Kh. Gersthof Czartoryskigasse WIFI Bednar- Währing Augarten Schubertpark Park Dr.- Josef- 10A Resch- Platz Evangelisches AlsergrundLichtensteinpark BUS Richthausenstraße Krankenhaus A.- Carlson- Wettsteinpark Anl. BUS Hernalser Hauptstr./Wattgasse Bezirksamt Max-Winter-Park Allgemeines Krankenhaus Verk.- Verm.- Venediger Au Hauptfeuerwache BUS Albrechtskreithgasse der Stadt Wien (AKH) Amt Amt Leopoldstadt W.- Leopoldstadt Hernals Bezirksamt Kössner- Leopoldstadt Volksprater Park BUS Wilhelminenstraße/Wattgasse (II.) Polizeidirektion Krankenhaus d. Barmherz. Brüder Confraternität-Privatklinik Josefstadt Rudolfsplatz DDSG Zirkuswiese BUS Ottakringer Str./Wattgasse Pass-Platz Ottakring Schönbornpark Rechnungshof Konstantinhügel BUS Schuhmeierplatz Herrengasse Josefstadt Arenawiese BUS Finanzamt Rathauspark U Stephansplatz Hasnerstraße Volksgarten WienU Finanzamt Jos.-Strauss-Park Volkstheater Heldenplatz U A BUS Possingergasse/Gablenzgasse U B.M.f. Finanzen U Arbeitsamt BezirksamtNeubau Burggarten Landstraße- Rochusgasse BUS Auf der Schmelz Mariahilf Wien Mitte / Neubau BezirksamtLandstraßeU -

![The Influence of Austrian Voting Right of 1907 on the First Electoral Law of the Successor States (Poland, Romania [Bukovina], Czechoslovakia)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0635/the-influence-of-austrian-voting-right-of-1907-on-the-first-electoral-law-of-the-successor-states-poland-romania-bukovina-czechoslovakia-190635.webp)

The Influence of Austrian Voting Right of 1907 on the First Electoral Law of the Successor States (Poland, Romania [Bukovina], Czechoslovakia)

ISSN 2411-9563 (Print) European Journal of Social Sciences May-August 2014 ISSN 2312-8429 (Online) Education and Research Volume 1, Issue 1 The influence of Austrian voting right of 1907 on the first electoral law of the successor states (Poland, Romania [Bukovina], Czechoslovakia) Dr Andrzej Dubicki Uniwersytet Łódzki Abstract As a result of collapse of the Central Powers in 1918 in Central Europe have emerged new national states e.g. Poland, Czechoslowakia, Hungaria, SHS Kingdom some of states that have existed before the Great War have changed their boundaries e.g. Romania, Bulgaria. But what is most important newly created states have a need to create their constituencies, so they needed a electoral law. There is a question in what manner they have used the solutions that have been used before the war in the elections held to the respective Parliaments (mostly to the Austrian or Hungarian parliament) and in case of Poland to the Tzarist Duma or Prussian and German Parliament. In the paper author will try to compare Electoral Laws that were used in Poland Czechoslowakia, and Romania [Bukowina]. The first object will be connected with the question in what matter the Austrian electoral law have inspired the solutions used in respective countries after the Great War. The second object will be connected with showing similarities between electoral law used in so called opening elections held mainly in 1919 in Austria-Hungary successor states. The third and final question will be connected with development of the electoral rules in respective countries and with explaining the reasons for such changes and its influence on the party system in respective country: multiparty in Czechoslovakia, hybrid in Romania. -

Opinions/Opinions – Standard Reference

01 April 1999 ACFC/SR(1999)006 ______ REPORT SUBMITTED BY THE CZECH REPUBLIC PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 1 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES ______ ACFC/SR(1999)006 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Czech Republic Information about Compliance with Principles set forth in the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities according to Article 25, Paragraph 1 of this Convention PART I Population of the Czech Republic according to National Identity and Mother Tongues8 (according to the 1991 public census) PART II SECTION I Article 1 Article 3 SECTION II Article 4 Article 5 Article 6 Article 7 Article 8 Article 9 Article 10 Article 11 Article 12 Article 13 Article 14 Article 15 Article 16 Article 17 Article 18 Article 19 Article 30 APPENDICES I. Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms (paper version only) Appendix No.II Statistical Overview of Racially Motivated Prosecuted Crimes(1998) Appendix No.IIIa Appendix No. IIIb Appendix No. IIIc 2 ACFC/SR(1999)006 The Czech Republic Information about Compliance with Principles set forth in the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities according to Article 25, Paragraph 1 of this Convention The Czech Republic signed the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (hereinafter referred to as the Convention) in Strasbourg on April 28, 1995. The Convention was approved by the Czech Parliament in accordance with Article 39, paragraph 4 of the Constitution of the Czech Republic as an international treaty on human rights and fundamental freedoms pursuant to Article 10 of the Czech Constitution. -

Svetozar Borevic, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-17-2021 Fuer Kaiser und Heimat: Svetozar Borevic, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War Sean Krummerich University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Krummerich, Sean, "Fuer Kaiser und Heimat: Svetozar Borevic, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War" (2021). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8808 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Für Kaiser und Heimat: Svetozar Boroević, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War by Sean Krummerich A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Darcie Fontaine, Ph.D. J. Scott Perry, Ph.D. Golfo Alexopoulos, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 30, 2021 Keywords: Serb, Croat, nationality, identity, Austria-Hungary Copyright © 2021, Sean Krummerich DEDICATION For continually inspiring me to press onward, I dedicate this work to my boys, John Michael and Riley. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of a score of individuals over more years than I would care to admit. First and foremost, my thanks go to Kees Boterbloem, Darcie Fontaine, Golfo Alexopoulos, and Scott Perry, whose invaluable feedback was crucial in shaping this work into what it is today. -

ÆTHELMEARC Ásta Vagnsdóttir. Name and Device. Azure, Two Bars

ACCEPTANCES Page 1 of 19 January 2007 LoAR THE FOLLOWING ITEMS HAVE BEEN REGISTERED: ÆTHELMEARC Ásta Vagnsdóttir. Name and device. Azure, two bars Or, overall an owl displayed argent. The use of an owl displayed is a step from period practice. Creature Twyne Dragon. Device. Per pale argent and sable all semy of fishhooks bendwise counterchanged. Please see the Cover Letter for a discussion on fishhooks. Desiderata Drake. Name. Maol Duín Ó Duinn. Name. Submitted as Máel-dúin O’Duinn, the submitter requested a name authentic for 15th C Ireland. As submitted, the name is unregisterable since the byname mixes the English patronymic marker O’ with the Irish patronym Duinn in violation of RfS III.1.a. This can be fixed by changing the marker to the Irish Ó. This change was specifically allowed by the submitter. The given name Máel-dúin is documented to before the 13th C; it is a Middle Irish form of the name inappropriate for use in the 15th C. The Annals of the Four Masters has a Magnus mac Maoile Duin in an entry for 1486. Irish bynames that use mac in this period are typically true patronymics; Magnus’s father almost certainly bore the given name Maol Duin. The normalized Early Modern Irish form of this name is Maol Duín; precedent holds that accents in Gaelic names must either be used consistently or dropped consistently. We have changed the name to Maol_Duín Ó Duinn, a fully Early Modern Irish form appropriate for the 15th C, in order to register it and to fulfill the submitter’s request for authenticity. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

Jindřich Toman

Jindřich Toman: Publications and Presentations Authored Books / Authored Books in Preparation / Edited Books / Translated Books / Articles and Book Chapters / Reviews / Miscellanea / Presentations Authored Books ______________________________________ 2009 Foto/montáž tiskem - Photo/Montage in Print. Praha: Kant (The Modern Czech Book, 2), 380 pp. ______________________________________ 2004 Kniha v českém kubismu / Czech Cubism and the Book. Praha: Kant (The Modern Czech Book, 1), 206 pp. _____________________________________ 1995 The Magic of a Common Language—Mathesius, Jakobson, Trubetzkoy and the Prague Linguistic Circle. Cambridge: MIT Press. 355 pp. • Also in Czech as Příběh jednoho moderního projektu: Pražský lingvistický kroužek, 1926-1948. Praha: Karolinum, 2011. ______________________________________ 1983 Wortsyntax: Eine Diskussion ausgewählter Probleme deutscher Wortbil- dung. Tübingen: Niemeyer. • Wortsyntax: [...] 2., erweiterte Auflage [Second, expanded edition]. Tübingen: Niemeyer. 1987. Current Book Projects ______________________________________ in prep. Projects, Conflicts, Change: Bohemia’s Jews and Their Nineteenth-century. in prep. Languages of Simplicity: Modernist Book Design in Interwar Czechoslo- vakia. Prague: Kant (The Modern Czech Book, 4.) Edited Books ______________________________________ 2017 Angažovaná čítanka Romana Jakobsona: Články, recenze, polemiky – 1920- 1945 a Moudrost starých Čechů. [Roman Jakobson’s Engaged Reader: Articles, Reviews, Polemics, 1920-1945]. Praha: Karolinum. ______________________________________ -

Czech Music and Politics from the Late 19Th Century to Early 20Th Century : Formation of a Modern Nation and the Role of Art Music

Czech Music and Politics from the Late 19th Century to Early 20th Century : Formation of a Modern Nation and the Role of Art Music Litt. D. Hisako NAITO 地域学論集(鳥取大学地域学部紀要) 第14巻 第2号 抜刷 REGIONAL STUDIES (TOTTORI UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF THE FACULTY OF REGIONAL SCIENCES) Vol.14 / No.2 平成30年3月12日発行 March 12, 2018 180308_3rd_抜粋論文表紙.indd 8 18/03/08 12:40 Czech Music and Politics from the Late 19th Century to Early 20th Century: Formation of a Modern Nation and the Role of Art Music Litt. D. Hisako NAITO* 19 世紀末から 20 世紀初頭のチェコ音楽と政治 - 近代国家の成立と芸術音楽の役割 - 内 藤 久 子* Key Words: Czech Music, National Revival, Cultural Nationalism, Czech Nationalist School, Hussite Revolution キーワード:チェコ音楽、民族再生、文化ナショナリズム、チェコ国民楽派、フス派革命 1. Culture and Nationalism — How were Music and Politics Related? The development of art, in particular the development of musical culture, has occasionally been influenced by strong political ideologies. Since musical development is strongly linked to the guiding principles of national policy, it can certainly be considered an important key for particular eras. Perhaps, the most striking example of this situation existed in Europe between the 19th and 20th centuries, a period characterized by the successive formation of new nations, each determining its own form of government. This occurred in several different contexts, for example, when nations (e.g., Hungary, Czech Republic, Poland, Norway, and Finland) were gaining independence from an empire, when nations were uniting with other nations from which they had previously separated (e.g., Italy and Germany), or when nations were undergoing a transition from monarchy to democracy (e.g., Great Britain and France). -

O Du Mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in The

O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 ABSTRACT O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 Copyright by Jason Stephen Heilman 2009 Abstract As a multinational state with a population that spoke eleven different languages, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was considered an anachronism during the age of heightened nationalism leading up to the First World War. This situation has made the search for a single Austro-Hungarian identity so difficult that many historians have declared it impossible. Yet the Dual Monarchy possessed one potentially unifying cultural aspect that has long been critically neglected: the extensive repertoire of marches and patriotic music performed by the military bands of the Imperial and Royal Austro- Hungarian Army. This Militärmusik actively blended idioms representing the various nationalist musics from around the empire in an attempt to reflect and even celebrate its multinational makeup. -

Caritas Pflege Zuhause Wien Pdf, 368 KB

Unsere Teams in Ihrer Nähe Es ist immer noch Seit die Frau Sie leben zu Hause und benötigen für den Alltag mein Leben. Unterstützung? Unsere Teams der Caritas Pflege Susi kommt, Zuhause sind für Sie da! Ein selbstbestimmtes Leben in den eigenen vier sind wir zwei Wänden braucht manchmal nur ganz wenig Hilfe. Pflege Zuhause Leopoldstadt Wir unterstützen Sie gerne dabei! für die Bezirke 2, 20 wieder sauber Tel 01-216 35 79 • Haben Sie Lust auf einen Einkaufsbummel? E-Mail: [email protected] Die Heimhelfer begleiten Sie zum Wochen- Pflege Zuhause beinand! markt oder in den Supermarkt. Pflege Zuhause Simmering für die Bezirke 3, 11 • Haben Sie heute etwas Besonderes vor? in Wien Tel 01-768 41 14 Unsere Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter E-Mail: [email protected] helfen Ihnen beim Aussuchen der Garderobe, beim Rasieren oder machen Ihnen eine Pflege Zuhause Innere Bezirke hübsche Frisur. für die Bezirke 1, 4-9 Tel 01-319 28 36 • Wie wäre es mit einem Spaziergang? E-Mail: [email protected] Regelmäßige Bewegung und frische Luft tun Körper und Seele gut und verbessern Pflege Zuhause Favoriten für den 10. Bezirk unsere Gedächtnisleistung. Tel 01-617 51 68 E-Mail: [email protected] Pflege Zuhause Dornbach Wir beraten und informieren Sie gerne! für die Bezirke 16-19 Tel 01-478 72 50 E-Mail: [email protected] Caritas Pflege Zuhause Wien Tel. 01-878 12-360 Pflege Zuhause Meidling für die Bezirke 12, 23 [email protected] Tel 01-815 69 34 www.caritas-pflege.at E-Mail: [email protected] Pflege Zuhause Wiental Tel 01-876 66 53 (für den 13. -

Language and Loss in Macha's Máj

ZTRACENÝ LIDSTVA RÁJ: LANGUAGE AND LOSS IN MACHA'S MÁJ By Alfred Th o mas I. Like all great national poets - Pushkin, Mickiewicz, Shevchenko - the Czech Romantic poet Karel Hynek Mácha (1810-1836) has become a cultural monument in his own country, the subject of an ever-growing mass of scholarship. Yet in his short life-time and for a period after his death, Macha's importance as a lyric poet of genius remained unrecognized in his nativeland. He evenincurred the disapproval andhostil- ity of his contemporaries for his refusal to conceive of literatuře in narrow nationalist terms. Since the beginnings of literary activity in the twelfth Century, Czech literatuře has been engagé, circumscribed by local political considerations. Its principál feature is insularity rather than universality. Mácha rejected the traditional role of the didactic author and thereby transgressed the orthodox values of the Obrození [National Revi- val]. In 1840 the nationalist playwright Josef Kajetán Tyl, author of Jan Hus, pres- ented a partial caricature of the Romantic Mácha in his story Rozervanec [literally, the one torn apart]. The title refers to the Byronic hero whose soul is divided by internal spirituál discord. Such a notion of division presupposes a humanistic ideal of unity and essence. By 'tearing aparť this ideal Mácha was in fact challenging the philosophical basis of the National Revival itself1. In the years following his death, Macha's reputation began to grow. In 1858 the almanach Máj was founded in his memory. Its co-editors were Vítězslav Hálek and Jan Neruda; its principál adherents were Karel Jaromír Erben, Božena Němcová, Karolina Světlá and Adolf Heyduk2.