Representations of Nationality in Carl Barks' Lost in the Andes and Voodoo Hoodoo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Religion & Society

Journal of Religion & Society Volume 6 (2004) ISSN 1522-5658 David, Mickey Mouse, and the Evolution of an Icon1 Lowell K. Handy, American Theological Library Association Abstract The transformation of an entertaining roguish figure to an institutional icon is investigated with respect to the figures of Mickey Mouse and the biblical King David. Using the three-stage evolution proposed by R. Brockway, the figures of Mickey and David are shown to pass through an initial entertaining phase, a period of model behavior, and a stage as icon. The biblical context for these shifts is basically irretrievable so the extensive materials available for changes in the Mouse provide sufficient information on personnel and social forces to both illuminate our lack of understanding for changes in David while providing some comparative material for similar development. Introduction [1] One can perceive a progression in the development of the figure of David from the rather unsavory character one encounters in the Samuel narratives, through the religious, righteous king of Chronicles, to the messianic abstraction of the Jewish and Christian traditions.2 The movement is a shift from “trickster,” to “Bourgeoisie do-gooder,” to “corporate image” proposed for the evolution of Mickey Mouse by Robert Brockway.3 There are, in fact, several interesting parallels between the portrayals of Mickey Mouse and David, but simply a look at the context that produced the changes in each character may help to understand the visions of David in three surviving biblical textual traditions in light of the adaptability of the Mouse for which there is a great deal more contextual data to investigate. -

Translations of Sound Effects in Seven Comics

KPOW, CHINK, SPLAT: Translations of Sound Effects in Seven Comics Vilma Kokko MA thesis University of Turku School of Languages and Translation Studies Department of English; English Translation and Interpreting May 2013 TURUN YLIOPISTO Kieli- ja käännöstieteiden laitos/humanistinen tiedekunta KOKKO, VILMA: KPOW, CHINK, SPLAT: Translations of Sound Effects in Seven Comics Pro gradu -tutkielma, 106 s. Englannin kieli, englannin kääntäminen ja tulkkaus Toukokuu 2013 Tämä pro gradu -tutkielma käsittelee äänitehosteiden kääntämistä sarjakuvissa. Tutkimus perustuu seitsemän eri sarjakuvan äänitehosteiden ja niiden suomennoksien vertailuun. Tutkitut tehosteet on kerätty yhdeksi korpukseksi kolmesta Aku Ankka -tarinasta, Tenavat- ja Lassi ja Leevi -stripeistä sekä Batman- ja Vartijat- sarjakuvaromaaneista. Sarjakuvat edustavat osittain eri genrejä, jotta saadaan tietoa erityyppisten sarjakuvien mahdollisesti erilaisista käännöskonventioista. Aku Ankka -sarjakuvien määrää on painotettu, jotta olisi mahdollista saada tarkempi kuva yhdestä yksittäisestä sarjakuvasta, jossa oletetaan äänitehosteiden pääsääntöisesti olevan käännettyjä. Äänitehosteita ja äänitehostekäännöksiä tutkitaan kahdesta eri näkökulmasta. Tutkielman ensimmäisessä osassa tarkastellaan äänitehosteissa käytettyjä käännösstrategioita ja etsitään seikkoja, jotka vaikuttavat eri käännösstrategioiden käyttöön ja tehosteiden kääntämiseen tai kääntämättä jättämiseen. Kaindlin (1999) esittelemää sarjakuvien käännösstrategiajaottelua verrataan Celottin (2008) kuvaan upotettuihin teksteihin -

Ankkakielen Meemit – Analyysi Aku Ankan Suomennosten Adaptaatioperäisestä Aineksesta

Ankkakielen meemit – analyysi Aku Ankan suomennosten adaptaatioperäisestä aineksesta Ville Viitanen Tampereen yliopisto Viestintätieteiden tiedekunta Monikielisen viestinnän ja käännöstieteen maisteriopinnot Englannin kääntämisen ja tulkkauksen opintosuunta Pro gradu -tutkielma Toukokuu 2017 Tampereen yliopisto Monikielisen viestinnän ja käännöstieteen maisteriopinnot viestintätieteiden tiedekunta VIITANEN, VILLE: Ankkakielen meemit – analyysi Aku Ankan suomennosten adaptaatioperäisestä aineksesta Monikielisen viestinnän pro gradu -tutkielma, 74 sivua + englanninkielinen lyhennelmä 16 sivua Toukokuu 2017 ___________________________________________________________________________ Käsittelen tutkielmassani Aku Ankka -sarjakuvalehden käännöskielelle ominaisia piirteitä ja niiden alkuperää. Selvitän vertailevan tekstianalyysin keinoin, millä tavoin lehdessä julkaistut suomennokset poikkeavat lähtöteksteistä, ja pohdin havaintojeni pohjalta, millaiset mekanismit kohdetekstiä mukauttavien käytäntöjen taustalla vaikuttavat. Taustoitan tutkimustani esittelemällä sarjakuvakääntämisen erityispiirteitä ja käytäntöjä sekä tutkimusaineistooni monin tavoin rinnastuvassa käännetyssä lastenkirjallisuudessa yleisiä adaptaatiota hyödyntäviä toimintatapoja. Teoreettisena viitekehyksenä käytän Georges L. Bastinin, Göte Klingbergin ja Zohar Shavitin adaptaatiotutkimusta ja havaintojeni erittelyn apuvälineenä Andrew Chestermanin esittämää Richard Dawkinsin kehittämään memetiikan käsitteeseen pohjautuvaa analyysimallia. Muodostan aiempien tutkimusten sekä ei-tieteellisten -

Ebook Download Walt Disneys Uncle Scrooge: the Seven Cities of Gold

WALT DISNEYS UNCLE SCROOGE: THE SEVEN CITIES OF GOLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Carl Barks | 234 pages | 02 Nov 2014 | FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS | 9781606997956 | English | United States Walt Disneys Uncle Scrooge: The Seven Cities of Gold PDF Book Fantagraphics' second release in this series focuses on Carl Barks's other protagonist and perhaps greatest creation: Scrooge McDuck. IDW's issues of Uncle Scrooge use a dual-numbering system, which count both how many issues IDW itself has published and what number issue it is in total for instance, IDW first issue's was billed as " 1 ". Next, Huey, Dewey, and Louie try to figure out how to prevent a runaway train from crashing when no one will listen! Plus: the oddball inventions of the ever-eccentric Gyro Gearloose! Carl Barks delivers another superb collection of all-around cartooning brilliance. Issue ST No image available. Tweet Clean. This book has pages of story and art, each meticulously restored and newly colored, as well as insightful story notes by an international panel of Barks experts. My new safe is locked against any form of burglary! Add to cart. Sound familiar? Naturally, Scrooge wants to claim it as his own. This edit will also create new pages on Comic Vine for: Beware, you are proposing to add brand new pages to the wiki along with your edits. And after donning a virtual reality headset, Donald and the boys find themselves menaced by creatures on other worlds. We made holiday shopping easy: browse by interest, category, price or age in our bookseller curated gift guide. Written by Carl Barks. -

Carl Barks and the Disney Comic Book: Unmasking the Myth of Modernity, 2006, 306 Pages, Tom Andrae, 1578068584, 9781578068586, Univ

Carl Barks and the Disney Comic Book: Unmasking the Myth of Modernity, 2006, 306 pages, Tom Andrae, 1578068584, 9781578068586, Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2006 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1GEVT1R http://goo.gl/RCwMW http://www.powells.com/s?kw=Carl+Barks+and+the+Disney+Comic+Book%3A+Unmasking+the+Myth+of+Modernity For over twenty-five years, Disney artist Carl Barks (1901-2000) created some of the most brilliant and funny stories in comic books. Gifted and prolific, he was the author of over five hundred tales in the most popular comic books of all time. Although he was never allowed to sign his name and worked in anonymity, Barks's unique artistic style and storytelling were immediately evident to all his readers. Barks created the town of Duckburg and a cast of characters that included Donald Duck's fabulously wealthy Uncle Scrooge, the lucky loafer Gladstone Gander, the daffy inventor Gyro Gearloose, the roguish crooks the Beagle Boys, and the Italian sorceress Magica de Spell. Carl Barks and the Disney Comic Book: Unmasking the Myth of Modernity is the first critical study of Barks's work in English. From a cultural studies perspective, the author analyzes all phases of Barks's career from his work in animation to his postretirement years writing the Junior Woodchucks stories. Andrae argues that Barks's oeuvre presents a vision strikingly different from the Disney ethos. Barks's central theme is a critique of modernity. His tales offer a mordant satire of Western imperialism and America's obsession with wealth, success, consumerism, and technological mastery, offering one of the few communal, ecological visions in popular culture. -

Donald Duck Has 225 Films to His Name

Donald Duck Has 225 Films To His Name National Donald Duck Day is observed annually on June 9th. This day commemorates the birthday of the funny animal cartoon character, Donald Duck. Donald made his first screen debut on June 9, 1934, in The Wise Little Hen. Donald Duck usually wears a sailor suit with a cap and a black or red bow tie and is most famous for his semi-intelligible speech along with his mischievous and irritable personality Donald Duck has appeared in more films than any other Disney character. Donald has 225 films to his name, according to IMDb. Donald was also declared in 2002 by TV Guide as one of the 50 greatest cartoon characters of all times. It was in Donald’s second appearance in Orphan’s Benefit that he was introduced to his comic friend, Mickey Mouse. Donald’s girlfriend, Daisy Duck, along with his nephews, Huey, Dewey, and Louie, were introduced shortly after that. In addition to animation, Donald is also known for his appearance in comic books and newspaper comic strips. One of Donald Duck’s famous sayings is “Oh boy, oh boy, oh boy.” The renowned early illustrators of Donald Duck were Al Taliaferro, Carl Barks and Don Rosa. Donald Duck first appeared as a drawing in a May 1934 issue of Good Housekeeping magazine promoting the film The Wise Little Hen. The magazine is sought after by collectors. Donald has gone on to star in seven feature films — which is more than any of his Disney counterparts. He is six years younger than Mickey Mouse. -

Don Rosan Ankkasarjakuvien Kulttuuri-Imperialistiset Piirteet

Don Rosan ankkasarjakuvien kulttuuri-imperialistiset piirteet Laura Kortelainen Tampereen yliopisto Kieli-, käännös- ja kirjallisuustieteiden yksikkö Monikielisen viestinnän ja käännöstieteen maisteriopinnot Englannin kääntämisen ja tulkkauksen opintosuunta Pro gradu -tutkielma Huhtikuu 2016 Tampereen yliopisto Kieli-, käännös- ja kirjallisuustieteiden yksikkö Monikielisen viestinnän ja käännöstieteen maisteriopinnot Englannin kääntämisen ja tulkkauksen opintosuunta KORTELAINEN, LAURA: Don Rosan ankkasarjakuvien kulttuuri-imperialistiset piirteet Pro gradu -tutkielma, 79 sivua + englanninkielinen lyhennelmä, 11 sivua Kevät 2016 Tämän tutkielman tavoitteena on tarkastella Don Rosan ankkasarjakuvien kulttuuri- imperialistisia piirteitä tarinoiden kuvan, tekstin ja ideologian välittämien amerikkalaisuuksien avulla. Tarkastelen myös sitä, onko amerikkalaisuuden välittymisessä eroja englanninkielisen lähdetekstin ja suomenkielisen käännöksen välillä. Teoriataustaltaan tutkielma nojaa Herbert Schillerin kulttuuri-imperialismin teoriaan, Itamar Even-Zoharin polysysteemiteoriaan sekä sarjakuvan ja sarjakuvan kääntämisen tutkimukseen. Kulttuuri-imperialismin teoreetikkojen mukaan yritysten poliittisiin ja sotilaallisiin intresseihin sidoksissa olevat kaupalliset pyrkimykset aiheuttavat ja ylläpitävät epätasa- arvoisia riippuvuussuhteita maiden välillä. Tärkeä osa teoriaa on ajatus siitä, että kulttuurilla ja erityisesti medialla on tärkeä asema identiteettien ja asenteiden luomisessa ja muokkaamisessa, minkä takia amerikkalaisen populaarikulttuurin -

A Pictorial History of Comic-Con

A PICTORIAL HISTORY OF COMIC-CON THE GOLDEN AGE OF COMIC-CON The 1970s were the formative years of Comic-Con. After finding its home in the El Cortez Hotel in downtown San Diego, the event continued to grow and prosper and build a national following. COMIC-CON 50 www.comic-con.org 1 OPPOSITE PAGE:A flier for the Mini-Con; the program schedule for the event. THIS PAGE: The Program Book featured a pre-printed cover of Balboa Park; photos from the Mini-Con, which were published in the Program Book for the first three-day MINI-CON Comic-Con held in August (clockwise MINI-CON from left): Forry Ackerman speaking; Mike Royer with some of his art; Comic-Con founding committee member Richard Alf NOTABLE MARCH 21, 1970 at his table; Ackerman at a panel discus- sion and with a fan; and Royer sketching GUESTS live on stage. The basement of the U.S. Grant Hotel, Downtown San Diego Attendance: 100+ Officially known as “San Diego’s Golden State Comic-Minicon” (the hyphen in Minicon comes and goes), this one-day event was held in March to raise funds for the big show in August, and FORREST J ACKERMAN was actually the first-ever West Coast comic convention. Most Comic-Con’s first-ever guest was the popular editor of Famous of those on the organizing com- Monsters of Filmland, the favorite mittee were teenagers, with the movie magazine of many of the major exceptions of Shel Dorf (a fans of that era. He paid his own recent transplant from Detroit way and returned to Comic-Con who had organized the Triple numerous times over the years. -

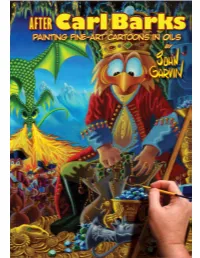

Barks's Personal Reference Library

AFTERCarl Barks painting fine-art cartoons in oils by Copyright 2010 by John Garvin www.johngarvin.com Published by Enchanted Images Inc. www.enchantedimages.com All illustrations in this book are copyrighted by their respective copy- right holders (according to the original copyright or publication date as printed in/on the original work) and are reproduced for historical reference and research purposes. Any omission or incorrect informa- tion should be transmitted to the publisher so it can be rectified in future editions of this book. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-9785946-4-0 First “Hunger Print” Edition November 2010 Edition size: 250 Printed in the United States of America about the “hunger” print “Hunger” (01-2010), 16” x 20” oil on masonite. “Hunger” was painted in early 2010 as a tribute to the painting genre pioneered by Carl Barks and to his techniques and craft. Throughout this book, I attempt to show how creative decisions – like those Barks himself might have made – helped shape and evolve the painting as I transformed a blank sheet of masonite into a fine-art cartoon painting. Each copy of After Carl Barks: Painting Fine-Art Cartoons in Oils includes a signed print of the final painting. 5 acknowledgements I am indebted to the following, in paintings and for being an important husband’s work. As the owner of alphabetical order: part of my life. -

Carl Barks' Donald Duck & Co Om Kvalitetene, Leserappellen Og

Carl Barks’ Donald Duck & Co Om kvalitetene, leserappellen og mangelen på anerkjennelse i norske litteraturhistorier Steinar Timenes Masteroppgave i Nordisk språk og litteratur Institutt for lingvistiske, litterære og estetiske studium UNIVERSITETET I BERGEN Først og fremst rettes den største takken til min familie som ga meg det første Donald-bladet fra barnsben av – for det har resultert i denne masteroppgaven. Takk til Arild Midthun og Egmont for bidragene deres! Takk til min veileder Erik Bjerck Hagen for å ha hatt troen på at prosjektet er gjennomførbart! Videre vil jeg takke alle de andre professorene i øverste etasje i HF-bygget for tysk irettesettelse og bergensk sjarm som har gjort studietiden til et akademisk Mekka! Takk for korrekturlesningen, Joakim Tjøstheim! Takk for alle de fuktige kveldene, Vingrisen! Til slutt vil jeg takke alle de flotte menneskene jeg har møtt og vennene jeg har fått under lektorutdanningen. Det er dere som gjør det verdt å komme ut i verdens beste yrke! 2 What is the future of comic books in the modern era? I’m very much scared that comics don’t have a very good future. There will have to be a cycle which reader interest goes back to reading again. Right now, it seems as everybody’s mind is caught up on these new games that come on television and things you can get by touching a button and watching a monitor. Pretty soon the mind will tire of those things and perhaps go back to reading. The wonderful thought of being alone with your thoughts and having something in your hand that you can just read and enjoy rather than having to sit in front of a television monitor looking at somebody else’s stuff moving around on the screen; You’re just a spectator you’re not doing anything to help yourself understand what’s going on. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: SONIC MOVIE MEMORIES: SOUND, CHILDHOOD, and AMERICAN CINEMA Paul James Cote, Doctor of Philosoph

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: SONIC MOVIE MEMORIES: SOUND, CHILDHOOD, AND AMERICAN CINEMA Paul James Cote, Doctor of Philosophy, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jonathan Auerbach, Department of English Literature Though the trend rarely receives attention, since the 1970s many American filmmakers have been taking sound and music tropes from children’s films, television shows, and other forms of media and incorporating those sounds into films intended for adult audiences. Initially, these references might seem like regressive attempts at targeting some nostalgic desire to relive childhood. However, this dissertation asserts that these children’s sounds are instead designed to reconnect audience members with the multi-faceted fantasies and coping mechanisms that once, through children’s media, helped these audience members manage life’s anxieties. Because sound is the sense that Western audiences most associate with emotion and memory, it offers audiences immediate connection with these barely conscious longings. The first chapter turns to children’s media itself and analyzes Disney’s 1950s forays into television. The chapter argues that by selectively repurposing the gentlest sonic devices from the studio’s films, television shows like Disneyland created the studio’s signature sentimental “Disney sound.” As a result, a generation of baby boomers like Steven Spielberg comes of age and longs to recreate that comforting sound world. The second chapter thus focuses on Spielberg, who incorporates Disney music in films like Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Rather than recreate Disney’s sound world, Spielberg uses this music as a springboard into a new realm I refer to as “sublime refuge” - an acoustic haven that combines overpowering sublimity and soothing comfort into one fantastical experience. -

Donald Duck Joins up the Walt Disney Studio

Where To Download Donald Duck Joins Up The Walt Disney Studio During World War Ii Donald Duck Joins Up The Walt Disney Studio During World War Ii pdf free donald duck joins up the walt disney studio during world war ii manual pdf pdf file Page 1/13 Where To Download Donald Duck Joins Up The Walt Disney Studio During World War Ii Donald Duck Joins Up The Donald Duck joins up: The Walt Disney Studio during World War II (Studies in cinema) Hardcover – January 1, 1982. by. Richard Shale (Author) › Visit Amazon's Richard Shale Page. Find all the books, read about the author, and more. Donald Duck joins up: The Walt Disney Studio during World ... Donald Duck Joins Up book. Read reviews from world’s largest community for readers. Donald Duck Joins Up: The Walt Disney Studio During World ... Donald Duck Joins Up: The Walt Disney Studio During World War II Studies in cinema no. 16 Issue 16 of Studies in cinema: Author: Richard Shale: Page 2/13 Where To Download Donald Duck Joins Up The Walt Disney Studio During World War Ii Edition: illustrated: Publisher: UMI Research Press,... Donald Duck Joins Up: The Walt Disney Studio During World ... He officially joins the army in 1942's Donald Gets Drafted, fights in the Pacific Theater in Commando Duck, and uses some futuristic camouflage to torment Drill Sergeant Pete in The Invisible Private. The untold truth of Donald Duck - looper.com Darth Maul with Donald Duck eyes, says "Join the Duck Side" directly below the Darth Maul version of Donald.