Journal of Religion & Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Disney Strike of 1941: from the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, Ljohnson [email protected]

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2008 The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Labor Relations Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Lisa, "The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective" (2008). Honors Projects Overview. 17. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/17 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective An Undergraduate Honors Project Presented By Lisa Johnson To The Department of History Approved: Project Advisor Date Chair, Department Honors Committee Date Department Chair Date The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective By Lisa Johnson An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in The Department of History The School of the Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2008 1 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 I. The Strike Page 5 II. The Unheard Struggles for Control: Intellectual Property Rights, Screen Credit, Workplace Environment, and Differing Standards of Excellence Page 17 III. The Historiography Page 42 Afterword Page 56 Bibliography Page 62 2 Introduction On May 28 th , 1941, seventeen artists were escorted out of the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California. -

Donald Duck: Timeless Tales Volume 1 Online

nLtTp (Free) Donald Duck: Timeless Tales Volume 1 Online [nLtTp.ebook] Donald Duck: Timeless Tales Volume 1 Pdf Free Romano Scarpa, Al Taliaferro, Daan Jippes audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC #877705 in Books Scarpa Romano 2016-05-31 2016-05-31Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 10.38 x .97 x 7.63l, .0 #File Name: 1631405721256 pagesDonald Duck Timeless Tales Volume 1 | File size: 54.Mb Romano Scarpa, Al Taliaferro, Daan Jippes : Donald Duck: Timeless Tales Volume 1 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Donald Duck: Timeless Tales Volume 1: 7 of 7 people found the following review helpful. Nice book, great stories.By Dutch DelightWho does not like Donald Duck? Great collection of European and American artists. The book is hard cover, nicely made. needs to package it better though. You can't just stuff inside a cardboard sleeve and mail and not expect some damage. Wrap it in paper first to prevent scuffs.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy Mark NYAlways loved this type of comics.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy GrantLove it Wak! IDW's first six issues of Donald Duck are gathered in this classy collectorsrsquo; volume... including great works by Romano Scarpa, Giorgio Cavazzano, Daan Jippesmdash;and the first-ever US publication of "The Diabolical Duck Avenger," Donald's classic 1960s debut as a super-anti-hero! With special extras for true Disney Comics aficionados, this Donald compendium provides hours of history and excitement. -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Master Syllabi

PELLISSIPPI STATE TECHNICAL COMMUNITY COLLEGE MASTER SYLLABUS INTRODUCTION TO FILM STUDIES HUM 2810 Class Hours: 3.0 Credit Hours: 3.0 Laboratory Hours: 0.0 Date Revised: Spring 03 Catalog Course Description: An overview of film history using selected world cinema feature films. Basic elements of film expression for understanding and analyzing narrative cinema. Some research is required. Entry Level Standards: Students must be able to read and write at the college level. Prerequisites: None Corequisites: None Textbook(s) and Other Reference Materials Basic to the Course: Text: Understanding Movies Films: in Media Center I. Week/Unit/Topic Basis: Week Topic 1 Note: Different film genres may be studied each semester. The following schedule outlines the classic mystery film genre. Introduction to course and syllabus - Best 100 films- Why study film? Various approaches to film study - Detective/mystery/crime genre in films; Technological factors behind film - Lumiere films (1895) - Melies film (1905); Homework: Read Understanding Movies, pages xi-17 Discuss Film Classification and Shots; Discuss factors in "Formalist Analysis of Classic Film Style "(handout); Screening: Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912, D.W. Griffith) 18 min.; Homework: Read pages 133-154, "Editing" 2 Discuss Continuity and Cutting; "Hollywood Behind the Badge" (police, crime, mystery genre films); Schedule a research paper; Homework: Read 112-123, "The Moving Camera" Oral research report (D.W. Griffith, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chapman); Discuss 7 Moving Camera Shots, etc.; Screening: -

Recommended Films: a Preparation for a Level Film Studies

Preparation for A-Level Film Studies: First and foremost a knowledge of film is needed for this course, often in lessons, teachers will reference films other than the ones being studied. Ideally you should be watching films regularly, not just the big mainstream films, but also a range of films both old and new. We have put together a list of highly useful films to have watched. We recommend you begin watching some these, as and where you can. There are also a great many online lists of ‘greatest films of all time’, which are worth looking through. Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 1941 Arguably the greatest film ever made and often features at the top of film critic and film historian lists. Welles is also regarded as one the greatest filmmakers and in this film: he directed, wrote and starred. It pioneered numerous film making techniques and is oft parodied, it is one of the best. It’s a Wonderful Life: Frank Capra, 1946 One of my personal favourite films and one I watch every Christmas. It’s a Wonderful Life is another film which often appears high on lists of greatest films, it is a genuinely happy and uplifting film without being too sweet. James Stewart is one of the best actors of his generation and this is one of his strongest performances. Casablanca: Michael Curtiz, 1942 This is a masterclass in storytelling, staring Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman. It probably has some of the most memorable lines of dialogue for its time including, ‘here’s looking at you’ and ‘of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine’. -

In 1925, Eight Actors Were Dedicated to a Dream. Expatriated from Their Broadway Haunts by Constant Film Commitments, They Wante

In 1925, eight actors were dedicated to a dream. Expatriated from their Broadway haunts by constant film commitments, they wanted to form a club here in Hollywood; a private place of rendezvous, where they could fraternize at any time. Their first organizational powwow was held at the home of Robert Edeson on April 19th. ”This shall be a theatrical club of love, loy- alty, and laughter!” finalized Edeson. Then, proposing a toast, he declared, “To the Masquers! We Laugh to Win!” Table of Contents Masquers Creed and Oath Our Mission Statement Fast Facts About Our History and Culture Our Presidents Throughout History The Masquers “Who’s Who” 1925: The Year Of Our Birth Contact Details T he Masquers Creed T he Masquers Oath I swear by Thespis; by WELCOME! THRICE WELCOME, ALL- Dionysus and the triumph of life over death; Behind these curtains, tightly drawn, By Aeschylus and the Trilogy of the Drama; Are Brother Masquers, tried and true, By the poetic power of Sophocles; by the romance of Who have labored diligently, to bring to you Euripedes; A Night of Mirth-and Mirth ‘twill be, By all the Gods and Goddesses of the Theatre, that I will But, mark you well, although no text we preach, keep this oath and stipulation: A little lesson, well defined, respectfully, we’d teach. The lesson is this: Throughout this Life, To reckon those who taught me my art equally dear to me as No matter what befall- my parents; to share with them my substance and to comfort The best thing in this troubled world them in adversity. -

The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation Interactive Edition

The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation Interactive Edition By Michelle L. Walsh Submitted to the Faculty of the Information Technology Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Information Technology University of Cincinnati College of Applied Science June 2006 The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation Interactive Edition by Michelle L. Walsh Submitted to the Faculty of the Information Technology Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Information Technology © Copyright 2006 Michelle Walsh The author grants to the Information Technology Program permission to reproduce and distribute copies of this document in whole or in part. ___________________________________________________ __________________ Michelle L. Walsh Date ___________________________________________________ __________________ Sam Geonetta, Faculty Advisor Date ___________________________________________________ __________________ Patrick C. Kumpf, Ed.D. Interim Department Head Date Acknowledgements A great many people helped me with support and guidance over the course of this project. I would like to give special thanks to Sam Geonetta and Russ McMahon for working with me to complete this project via distance learning due to an unexpected job transfer at the beginning of my final year before completing my Bachelor’s degree. Additionally, the encouragement of my family, friends and coworkers was instrumental in keeping my motivation levels high. Specific thanks to my uncle, Keith -

Winter 2015 • Volume24 • Number4

Winter 2015 • Volume24 • Number4 If Disney Files Magazine was a grocery store tabloid, the headline on this edition’s cover may read: Giant Reptile to Terrorize China! Of course, we’d never resort to such sensationalism, even if we are ridiculously excited about the imposing star of the Roaring Rapids attraction in the works for Shanghai Disneyland (pages 3-8). We take ourselves far too seriously for such nonsense. Wait a minute. What am I saying? This isn’t exactly a medical journal, and anyone who’s ever read the fine print at the bottom of this page knows that, if there’s one thing we embrace in theDisney Files newsroom, it’s nonsense! So at the risk of ending our pursuit of a Pulitzer (close as we were), I introduce this issue with a series of headlines crafted with all the journalistic integrity of rags reporting the births of alien babies, celebrity babies…and alien-celebrity babies. Who wore it best? Disney’s Beach Club Villas vs. the Brady family! (Page 13) Evil empire mounting Disney Parks takeover! (Pages 19-20) Prince Harry sending soldiers into Walt Disney World battle! (Page 21) An Affleck faces peril at sea! (Page 24) Mickey sells Pluto on the street! (Page 27) Underage driver goes for joy ride…doesn’t wear seatbelt! (Page 30) Somewhere in Oregon, my journalism professors weep. All of us at Disney Vacation Club wish you a happy holiday season and a “sensational” new year. Welcome home, Ryan March Disney Files Editor Illustration by Keelan Parham VOL. 24 NO. -

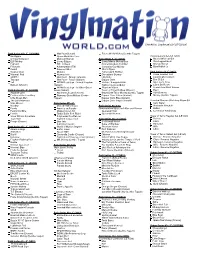

VM Checklist

Checklist (Updated 10/15/2013) Park Series #1 - 3” (12/19/08) Wet Paint Donald Future World Mickey (Combo Topper) Bad Apple Space Mountain Paris Contemporary Set (LE 1200) Creepy Wallpaper Monorail Orange Park Series 9 - 3” (2012) Native American Girl ELP Mickey Sonny Eclipse Camp Minnie Mickey Bear Five Legged Goat Figment DCL Lifeboat Animal Kingdom Fruit Bat Orange Owl Jr. Fireworks Adventureland Tiki Castaway Cay Mickey Blue Rabbit Jr. Kermit Primeval Whirl Flick’s Flyers Magical Stars Monstro Fantasyland Dumboi Park Series 13 3” (2013) Monorail Red Norway Troll Disneyland Skyway Three Headed Troll SMRT-1 Wet Paint - Orange (Variant) Lilly Belle Catastrophe Canyon Teacups Wet Paint - Purple (Variant) Dapper Dans Box O’ Bot Yeti WDW Road Sign - Animal Kingdom Frozen Pineapple Drink Injun Joe’s Cave Balloon (Chaser) (Variant) Typhoon Lagoon Gator Claire De Room WDW Road Sign - All Other Guest Phantom Manor Trader Sam/Chief Namee Park Series #2 - 3” (5/22/09) Areas (Variant) Tower of Terror Bellhop (Chaser) Devil Aquaramouse Abraham Lincoln (Chaser) Brave Little Tailor Mickey (Combo Topper) TBA (Chaser) Festival of the Lion King Runaway Brain Mickey (Combo Dapper Dans Yellow (Variant) Mickey (Combo Topper) Little Green Men Topper) Dapper Dans Blue (Variant) The Little Mermaid Dapper Dans Purple (Variant) Haunted Mansion Stretching Room Set Mike Mouse Park Series #7 - 3” Sally Slater Monkey Donald Philharmagic Park Series #9 -Sets Alexander Nitrokoff Panda America on Parade Tomorrowland Spacesuit Man and Woman Hobbs Penny Machine Muppet -

Walt Disney Classified: WEFT and the 3-Point Identification Systems

Walt Disney Classified: WEFT and the 3-Point Identification Systems By David A. Bossert (Title card for the WEFT System of Aircraft Identification, 1943) On December 8, 1941, the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor Naval Base on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, Walt Disney received a call from a Naval Officer in Washington, DC. The call from Navy Lieutenant Cottle was to offer Walt Disney Productions a contract for approximately twenty training films on ship and aircraft identification. The actual number of films changed over time as the requirements shifted. (1) This contract was a direct result of correspondence between the studio and a Lieutenant Hutchinson in November 1941 outlining the need for these training films and the specifications of how they would be created. These first Military training films were the WEFT, an acronym for Wings, Engine, Fuselage and Tail, and the 3-Point Identification System for recognizing and distinguishing between friendly and enemy aircraft and Navy ships. Hutchinson had corresponded with the Disney Studio on the Navy’s need for this series of films that could train military personnel in identifying aircraft and naval ships. That correspondence dictated the requirements needed by the Navy and the response detailed what the studio could provide to satisfy the need. Walt had determined that the films didn’t need to be in color and that black and white 35MM film would be the best approach for the series of films. (2) Although, it would have been less expensive to use 16MM, using the larger format 35MM film was better suited for the planned double-exposure special effects that were to be used in illustrating clearly the various educational points. -

The Disney Bloodline

Get Your Free 150 MB Website Now! THE SKILL OF LYING, THE ART OF DECEIT The Disney Bloodline The Illuminati have refined the art of deception far beyond what the common man has imagined. The very life & liberty of humanity requires the unmasking of their deceptions. That is what this book is about. Honesty is a necessary ingredient for any society to function successfully. Deception has become a national pastime, starting with our business and political leaders and cascading down to the grass roots. The deceptions of the Illuminati's mind-control may be hidden, but in their wake they are leaving tidal waves of distrust that are destroying America. While the CIA pretend to have our nations best interest at heart, anyone who has seriously studied the consequences of deception on a society will tell you that deception will seriously damage any society until it collapses. Lies seriously damage a community, because trust and honesty are essential to communication and productivity. Trust in some form is a foundation upon which humans build relationships. When trust is shattered human institutions collapse. If a person distrusts the words of another person, he will have difficulty also trusting that the person will treat him fairly, have his best interests at heart, and refrain from harming him. With such fears, an atmosphere of death is created that will eventually work to destroy or wear down the cooperation that people need. The millions of victims of total mind- control are stripped of all trust, and they quietly spread their fears and distrust on a subconscious level throughout society.