Wildland Fire Admin Performance Report (04P-11)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Health Risk Assessment of Wildland Fire-Fighting Chemicals: Long-Term Fire Retardants

HUMAN HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENT OF WILDLAND FIRE-FIGHTING CHEMICALS: LONG-TERM FIRE RETARDANTS Prepared for: Fire and Aviation Management U.S. Forest Service By: Headquarters: 1406 Fort Crook Drive South, Suite 101 Bellevue, NE 68005 September 2017 Health Risk Assessment: Retardants September 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENT OF WILDLAND FIRE-FIGHTING CHEMICALS: LONG-TERM FIRE RETARDANTS September 2017 The U.S. Forest Service uses a variety of fire-fighting chemicals to aid in the suppression of fire in wildlands. These products can be categorized as long-term retardants, foams, and water enhancers. This chemical toxicity risk assessment of the long-term retardants examined their potential impacts on fire-fighters and members of the public. Typical and maximum exposures from planned activities were considered, as well as an accidental drench of an individual in the path of an aerial drop. This risk assessment evaluates the toxicological effects associated with chemical exposure, that is, the direct effects of chemical toxicity, using methodologies established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. A risk assessment is different from and is only one component of a comprehensive impact assessment of all types of possible effects from an action on health and the human environment, including aircraft noise, cumulative impacts, physical injury, and other direct or indirect effects. Environmental assessments or environmental impact statements pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act consider chemical toxicity, as well as other potential effects to make management decisions. Each long-term retardant product used in wildland fire-fighting is a mixture of individual chemicals. The product is supplied as a concentrate, in either a wet (liquid) or dry (powder) form, which is then diluted with water to produce the mixture that is applied during fire-fighting operations. -

Canadian Wildland Fire Glossary

Canadian Wildland Fire Glossary CIFFC Training Working Group December 10, 2020 i Preface The Canadian Wildland Fire Glossary provides the wildland A user's guide has been developed to provide guidance on fire community a single source for accurate and consistent the development and review of glossary entries. Within wildland fire and incident management terminology used this guide, users, working groups and committees can find by CIFFC and its' member agencies. instructions on the glossary process; tips for viewing the Consistent use of terminology promotes the efficient glossary on the CIFFC website; guidance for working groups sharing of information, facilitates analysis of data from and committees assigned ownership of glossary terms, disparate sources, improves data integrity, and maximizes including how to request, develop, and revise a glossary the use of shared resources. The glossary is not entry; technical requirements for complete glossary entries; intended to be an exhaustive list of all terms used and a list of contacts for support. by Provincial/Territorial and Federal fire management More specifically, this version reflects numerous additions, agencies. Most terms only have one definition. However, deletions, and edits after careful review from CIFFC agency in some cases a term may be used in differing contexts by staff and CIFFC Working Group members. New features various business areas so multiple definitions are warranted. include an improved font for readability and copying to word processors. Many Incident Command System The glossary takes a significant turn with this 2020 edition Unit Leader positions were added, as were numerous as it will now be updated annually to better reflect the mnemonics. -

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems OSHA 3256-09R 2015 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.” This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards- related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts. Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required. This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627. This guidance document is not a standard or regulation, and it creates no new legal obligations. It contains recommendations as well as descriptions of mandatory safety and health standards. The recommendations are advisory in nature, informational in content, and are intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards and regulations promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. -

Pre's Mom Dies at 88

C M C M Y K Y K TAKING CHARGE New MHS coach hits the ground running, B1 See be SUM low for MER SIZ Your ZLER Choice Event B AY AP PLIAN THE CE & TV MATTR STORE ESS Serving Oregon’s South Coast Since 1878 THURSDAY,JULY 18, 2013 RV Jamboree opens door for more tourism BY TIM NOVOTNY The World NORTH BEND — The Bay Area is starting to reap the rewards of a massive motor coach rally that took place in 2012. Today will conclude the Oregon Coast RV Jamboree, a new event at The Mill Casino-Hotel sponsored by Guaranty RV Super Centers. The event saw dozens of vehicles visiting, and included a Menasha forest tour and traditional tribal salmon bake. Ray Doering, communications manager for the Mill, says the Bay Area can expect more of these rallies in the future coming off the success of last year’s massive Family Motor Coach Association Northwest Rally. File photo by Lou Sennick, The World Elfriede Prefontaine, second from left, the mother of the late Steve Prefontaine died in Eugene on Wednesday at the age of 88. Here, she SEE JAMBOREE | A10 attended the dedication of the Prefontaine Track at Marshfield High School on April 28, 2001. Daughter Linda Prefontaine is on the right in the brown coat. Pre’s mom dies at 88 FROM STAFF AND that Prefontaine had been hospital- the University of Oregon, setting WIRE SERVICE REPORTS ized after suffering a fall at her assist- seven American records in distance ed living facility. track events. COOS BAY — The last surviving Born in Germany, Elfriede met her He competed in the 1972 Olympic husband Raymond in 1946 when he parent of legendary runner Steve Games in Munich before he died in a was an occupying U.S. -

A Preparedness Guide for Firefighters and Their Families

A Preparedness Guide for Firefighters and Their Families JULY 2019 A Preparedness Guide for Firefighters and Their Families July 2019 NOTE: This publication is a draft proof of concept for NWCG member agencies. The information contained is currently under review. All source sites and documents should be considered the authority on the information referenced; consult with the identified sources or with your agency human resources office for more information. Please provide input to the development of this publication through your agency program manager assigned to the NWCG Risk Management Committee (RMC). View the complete roster at https://www.nwcg.gov/committees/risk-management-committee/roster. A Preparedness Guide for Firefighters and Their Families provides honest information, resources, and conversation starters to give you, the firefighter, tools that will be helpful in preparing yourself and your family for realities of a career in wildland firefighting. This guide does not set any standards or mandates; rather, it is intended to provide you with helpful information to bridge the gap between “all is well” and managing the unexpected. This Guide will help firefighters and their families prepare for and respond to a realm of planned and unplanned situations in the world of wildland firefighting. The content, designed to help make informed decisions throughout a firefighting career, will cover: • hazards and risks associated with wildland firefighting; • discussing your wildland firefighter job with family and friends; • resources for peer support, individual counsel, planning, and response to death and serious injury; and • organizations that support wildland firefighters and their families. Preparing yourself and your family for this exciting and, at times, dangerous work can be both challenging and rewarding. -

Doi105-Archived.Pdf

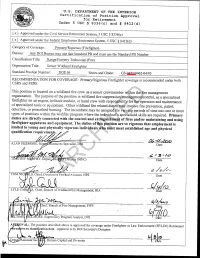

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Certification of Position Approval for Retirement Under 5 use§ 8336(c) and§ 8412(d) [ x] Approved under the Civil Service Retirement System, 5 USC§ 8336(c) [ x] Approved under the Federal Employees Retirement System, 5 USC§ 8412(d) Category of Coverage: Primary/Rigorous (Firefighter), Bureau: Any DOI Bureau may use tru.s Standard PD and must use the Standard PD Number Classification Title: Range/Forestry Technician (Fire) Organization Title: Senior Wildland Firefighter Standard Position Number: DO1105 Series and Grade: GS-0455/0462-04/05 RECOMMENDATION FOR COVERAGE: Primary/Rigorous Firefighter coverage is recommended under both CSRS and FERS. This position is located on a wildland fire crew as.a senior crewmember within the fire management organization. The purpose of the position is wildland fire suppression/management/control, as a specialized firefighter on an engine, helitack module, or hand crew with responsibility for the operation and maintenance of specialized tools or equipment. Other wildland fire related duties may involve fire prevention, patrol, detection, or prescribed burning. The incumbent may be assigned for varying periods of time into one or more types of positions within the wildfire program where the individual's specialized skills are required. Primary duties are directly connected with the control and extinguishment of fires and/or maintaining and using firefighter apparatus and equipment. The duties of this position are so rigorous that employment is limited to young and physically vigorous individuals who must meet established age and physical qualification requirements. .. a4..zo10 Date ~ - 5 -/~ T Date ARCHIVED Date ~/cJro E, Chief, Branch ofWildland Fire Management, BIA Date 1 . -

Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide PMS 210 April 2013 Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide April 2013 PMS 210 Sponsored for NWCG publication by the NWCG Operations and Workforce Development Committee. Comments regarding the content of this product should be directed to the Operations and Workforce Development Committee, contact and other information about this committee is located on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Questions and comments may also be emailed to [email protected]. This product is available electronically from the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Previous editions: this product replaces PMS 410-1, Fireline Handbook, NWCG Handbook 3, March 2004. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) has approved the contents of this product for the guidance of its member agencies and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone else. NWCG’s intent is to specifically identify all copyrighted content used in NWCG products. All other NWCG information is in the public domain. Use of public domain information, including copying, is permitted. Use of NWCG information within another document is permitted, if NWCG information is accurately credited to the NWCG. The NWCG logo may not be used except on NWCG-authorized information. “National Wildfire Coordinating Group,” “NWCG,” and the NWCG logo are trademarks of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names or trademarks in this product is for the information and convenience of the reader and does not constitute an endorsement by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group or its member agencies of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. -

Humboldt County Fire Services

Humboldt County Fire Services FIRE CHIEFS' ASSOCIATION OF HUMBOLDT COUNTY Annual Report 2011 To: Humboldt County Board of Supervisors An overview of the Humboldt County Fire Service of 2011 The Fire Service in Humboldt County continues to grow in a positive direction, constantly working towards the goal of promoting county‐wide adoption of procedures and policies through the Fire Chief’s Association with input and regulation from the various groups with‐in such as the Training Instructors, Fire Prevention Officers and the Fire/Arson Investigation Unit. This positive and forward direction is an indication of the great working relationships that have developed among the various departments over the years, and that continues to improve, a feat that is not easy in such a rural setting. These relationships have allowed the fire agencies to foster a team approach both from an operational and an administrative stand point. The effort of forming fire districts for some of the volunteer fire companies with‐in the county, along with the modification of district boundaries in an attempt to provide a better system of protection for many of the Counties’ residents, continues with the help of the Fire Safe Council and County Planning with the support of the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors. The Fire Chief’s Association would like to acknowledge their appreciation of that consideration and support from the Board. At the same time the Chief’s Association recognizes that the future of the fire service in Humboldt County is dependent upon the Board’s continued support. With fees now being levied by the State in the way of “Fire Prevention Fees” to the residents residing in State Responsibility Areas, there is major concern that funding for many of the rural departments will suffer which makes support by the Board of Supervisors a critical factor in their very survival. -

2021 Active Business Licenses, 6/7/21

2021 ACTIVE BUSINESS LICENSES, 6/7/21 Business Name Location Location City Description AUCTION COMPANY OF SOUTHERN OR 347 S BROADWAY COOS BAY Auctions 101 COASTAL DETAILING & ATV REPAIR 1889 N BAYSHORE DR COOS BAY Auto/Equipment Repair METRIC MOTORWORKS, INC. 3500 OCEAN BLVD SE COOS BAY Auto/Equipment Repair PRO TOWING 63568 WRECKING ROAD COOS BAY Auto/Equipment Repair 1996 LLC DBA CHAMBERS CONSTRUCTION COMPA 3028 JUDKINS RD STE 1 EUGENE General Contractors 4C'S ENVIRONMENTAL INC 1590 SE UGLOW AVE DALLAS General Contractors 7 MILE CONTRACTING LLC 48501 HWY 242 BROADBENT General Contractors A AND R SOLAR SPC 6800 NE 59TH PL PORTLAND General Contractors ABSOLUTE ROOFING AND MAINTENANCE LLC 92589 DUNES LN NORTH BEND General Contractors AC SCHOMMER & SONS, INC. 6421 NE COLWOOD PORTLAND General Contractors ACACIA II 501 N 10TH ST COOS BAY General Contractors ACTIVE FLOW, LLC 63569 SHINGLEHOUSE RD COOS BAY General Contractors ADAIR HOMES, INC 172 MELTON RD CRESWELL General Contractors AECOM TECHNICAL SERVICES, INC 111 SW COLUMBIA ST STE 1500 PORTLAND General Contractors AJP CONSTRUCTION 1682 APPLEWOOD DR COOS BAY General Contractors ALL AROUND SIGNS 69777 STAGE RD COOS BAY General Contractors ALL COAST HEATING & AIR , LLC 68212 RAVINE NORTH BEND General Contractors ALL NATURAL PEST ELIMINATION 3445 S PACIFIC HWY MEDFORD General Contractors AMERICAN CARPORTS, INC. 457 N BROADWAY ST JOSHUA General Contractors AMERICAN INDUSTRIAL DOOR, LLC 515 N LAKE RD COOS BAY General Contractors AMP CONSTRUCTION LLC 50147 HIGHWAY 101 BANDON General Contractors ANGLE & SQUARE LLC 2067 ROYAL SAINT GEORGE DR FLORENCE General Contractors APOLLO MECHANICAL CONTRACTORS 1207 W COLUMBIA DR KENNEWICK General Contractors APPLIED REFRIGERATION TECH INC 6608 TABLE ROCK RD STE 3 MEDFORD General Contractors ARCADIA ENVIRONMENTAL, INC 3164 OCEAN BLVD S.E. -

Forest Service Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center Wildland Fire

Forest Service Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center Wildland Fire Program 2016 Annual Report Weber Basin Job Corps: Above Average Performance In an Above Average Fire Season Brandon J. Everett, Job Corps Forest Area Fire Management Officer, Uinta-Wasatch–Cache National Forest-Weber Basin Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center The year 2016 was an above average season for the Uinta- Forest Service Wasatch-Cache National Forest. Job Corps Participating in nearly every fire on the forest, the Weber Basin Fire Program Job Corps Civilian Conservation Statistics Center (JCCCC) fire program assisted in finance, fire cache and camp support, structure 1,138 students red- preparation, suppression, moni- carded for firefighting toring and rehabilitation. and camp crews Weber Basin firefighters re- sponded to 63 incidents, spend- Weber Basin Job Corps students, accompanied by Salt Lake Ranger District Module Supervisor David 412 fire assignments ing 338 days on assignment. Inskeep, perform ignition operation on the Bear River RX burn on the Bear River Bird Refuge. October 2016. Photo by Standard Examiner. One hundred and twenty-four $7,515,675.36 salary majority of the season commit- The Weber Basin Job Corps fire camp crews worked 148 days paid to students on ted to the Weber Basin Hand- program continued its partner- on assignment. Altogether, fire crew. This crew is typically orga- ship with Wasatch Helitack, fire assignments qualified students worked a nized as a 20 person Firefighter detailing two students and two total of 63,301 hours on fire Type 2 (FFT2) IA crew staffed staff to that program. Another 3,385 student work assignments during the 2016 with administratively deter- student worked the entire sea- days fire season. -

Fire Management.Indd

Fire today ManagementVolume 65 • No. 2 • Spring 2005 LLARGEARGE FFIRESIRES OFOF 2002—P2002—PARTART 22 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Erratum In Fire Management Today volume 64(4), the article "A New Tool for Mopup and Other Fire Management Tasks" by Bill Gray shows incorrect telephone and fax numbers on page 47. The correct numbers are 210-614-4080 (tel.) and 210-614-0347 (fax). Fire Management Today is published by the Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. The Secretary of Agriculture has determined that the publication of this periodical is necessary in the transaction of the pub- lic business required by law of this Department. Fire Management Today is for sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, at: Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: 202-512-1800 Fax: 202-512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 Fire Management Today is available on the World Wide Web at http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/fmt/index.html Mike Johanns, Secretary Melissa Frey U.S. Department of Agriculture General Manager Dale Bosworth, Chief Robert H. “Hutch” Brown, Ph.D. Forest Service Managing Editor Tom Harbour, Director Madelyn Dillon Fire and Aviation Management Editor Delvin R. Bunton Issue Coordinator The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communica- tion of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720- 2600 (voice and TDD). -

Firefighter Wood Product and Building Systems Awareness: a Resource Guide

FIREFIGHTER WOOD PRODUCT AND BUILDING SYSTEMS AWARENESS: A RESOURCE GUIDE Lia Bishop, Martha Dow, Len Garis and Paul Maxim March 2015 CENTRE FOR SOCIAL RESEARCH Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 2 FIREFIGHTING AWARENESS AND RESPONSE RESOURCES: AN INTRODUCTION ...................................... 2 BUILDING CONSTRUCTION AWARENESS ............................................................................................................. 2 General .................................................................................................................................................. 2 CONSTRUCTION SITE AWARENESS ..................................................................................................................... 4 WOOD BUILDINGS AND FIRE SAFETY ............................................................................................ 4 FIRE PROTECTION AND STATISTICS, BUILDING AND FIRE CODES, STRUCTURAL DESIGN .............................................. 4 Fire Protection and Statistics ................................................................................................................. 4 ELEMENTS OF FIRE SAFETY IN WOOD BUILDING CONSTRUCTION ........................................................................... 8 General Fire Performance: Charring, Flame Spread and Fire Resistance .............................................. 8 Lightweight Wood-frame Construction – Including