The Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Preventing Violent Extremism in Kyrgyzstan

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Jacob Zenn and Kathleen Kuehnast This report offers perspectives on the national and regional dynamics of violent extremism with respect to Kyrgyzstan. Derived from a study supported by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) to explore the potential for violent extremism in Central Asia, it is based on extensive interviews and a Preventing Violent countrywide Peace Game with university students at Kyrgyz National University in June 2014. Extremism in Kyrgyzstan ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jacob Zenn is an analyst on Eurasian and African affairs, a legal adviser on international law and best practices related to civil society and freedom of association, and a nonresident research Summary fellow at the Center of Shanghai Cooperation Organization Studies in China, the Center of Security Programs in Kazakhstan, • Kyrgyzstan, having twice overthrown autocratic leaders in violent uprisings, in 2005 and again and The Jamestown Foundation in Washington, DC. Dr. Kathleen in 2010, is the most politically open and democratic country in Central Asia. Kuehnast is a sociocultural anthropologist and an expert on • Many Kyrgyz observers remain concerned about the country’s future. They fear that underlying Kyrgyzstan, where she conducted field work in the early 1990s. An adviser on the Central Asia Fellows Program at the socioeconomic conditions and lack of public services—combined with other factors, such as Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington drug trafficking from Afghanistan, political manipulation, regional instability in former Soviet University, she is a member of the Council on Foreign Union countries and Afghanistan, and foreign-imported religious ideologies—create an envi- Relations and has directed the Center for Gender and ronment in which violent extremism can flourish. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

Uzbek: War, Friendship of the Peoples, and the Creation of Soviet Uzbekistan, 1941-1945

Making Ivan-Uzbek: War, Friendship of the Peoples, and the Creation of Soviet Uzbekistan, 1941-1945 By Charles David Shaw A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair Professor Victoria Frede-Montemayor Professor Victoria E. Bonnell Summer 2015 Abstract Making Ivan-Uzbek: War, Friendship of the Peoples, and the Creation of Soviet Uzbekistan, 1941-1945 by Charles David Shaw Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair This dissertation addresses the impact of World War II on Uzbek society and contends that the war era should be seen as seen as equally transformative to the tumultuous 1920s and 1930s for Soviet Central Asia. It argues that via the processes of military service, labor mobilization, and the evacuation of Soviet elites and common citizens that Uzbeks joined the broader “Soviet people” or sovetskii narod and overcame the prejudices of being “formerly backward” in Marxist ideology. The dissertation argues that the army was a flexible institution that both catered to national cultural (including Islamic ritual) and linguistic difference but also offered avenues for assimilation to become Ivan-Uzbeks, part of a Russian-speaking, pan-Soviet community of victors. Yet as the war wound down the reemergence of tradition and violence against women made clear the limits of this integration. The dissertation contends that the war shaped the contours of Central Asian society that endured through 1991 and created the basis for thinking of the “Soviet people” as a nation in the 1950s and 1960s. -

Nominative Principles of Clothing Terms in the Karakalpak Language

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 13, 2020 NOMINATIVE PRINCIPLES OF CLOTHING TERMS IN THE KARAKALPAK LANGUAGE Zayrova Kanshayim Muratbaevna Karakalpak State University doctoral student Scientific supervisor: associate professorSeytnazarova I.E. Nukus (Uzbekistan) Received: 14 March 2020 Revised and Accepted: 8 July 2020 ABSTRACT: In the article the history, culture, national values of our people, and the names of clothing which is a kind of the material culture of our people, which had a number of historical epochs, lived with the nation and their naming nominative principles are analyzed by historical-etymological side. In particular, the peculiarities of the terms of old clothes which become to be forgotten, the history of the origin of the terms, the naming principles were revealed. The names of clothing as the other terms in the language do not appear spontaneously, but their appearance develops according to the psychology of thinking of the people, the mentality of their own. The lexicon of clothing was considered as a system of special onomas. Depending on the appearance of the terms of clothing, it is said that it is carried out in the form of imitation (analogy), imaginary imitation (symbolism). KEYWORDS: Lexicology, clothing lexicon, lexeme, historical-etymology, analogy, nominative principle, material principle: leather, wool, jeep (thread), silk, cotton; functional principle: hat, cap, jawlik (scarf), kerchief; analogical principle: sen‟sen‟ ton (coat), jelek, oraypek, etc. I. INTRODUCTION If clothing has been a means of protecting humanity from external influences since ancient times, then its functions have expanded. Thus, in addition to protecting people from external influences, clothing began to reflect the factors of social development, as well as a collection of objects that cover, wrap and decorate the human body. -

Balkan Reader

Stephen Bonsal, Leon Dennon, Henry Pozzi: Balkan Reader First-hand reports by Western correspondents and diplomats for over a century Edited by Andrew L. Simon Copyright © 2000 by Andrew L. Simon Library of Congress Card Number: 00-110527 ISBN: 1-931313-00-8 Distributed by Ingram Book Company Printed by Lightning Source, La Vergne, TN Published by Simon Publications, P.O. Box 321, Safety Harbor, FL Contents Introduction 1 The Authors 5 Bulgaria Stephen Bonsal; 1890: 11 Leon Dennen; 1945: 64 Yugoslavia Stephen Bonsal; 1890: 105 Stephen Bonsal; 1920: 147 John F. Montgomery; 1947: 177 Henry Pozzi; 1935: 193 Ultimatum to Serbia: 224 Leon Dennen; 1945: 229 Romania Stephen Bonsal; 1920: 253 Harry Hill Bandholtz; 1919: 261 Leon Dennen; 1945: 268 Macedonia and Albania Stephen Bonsal; 1890: 283 Henry Pozzi; 1935: 315 Appendix Repington; 1923: 333 Introduction About 100 years ago, the Senator from Minnesota, Cushman Davis in- quired from Stephen Bonsal, foreign correspondent of the New York Her- ald: “Why do not the people of Macedonia and of the Balkans generally, leave off killing one another, burning down each others’ houses, and do what is right?” “Unfortunately”, Bonsal replied, “they are convinced that they are doing what is right. The blows they strike they believe are struck in the most righ- teous of causes. If they could only be inoculated with the virus of modern skepticism and leave off doing right so fervently, there might come about an era of peace in the Balkans—and certainly the population would in- crease. As full warrant and justification of their merciless warfare, the Christians point to Jushua the Conqueror of the land of Canaan, the Turks to Mahomet. -

The Complete Costume Dictionary

The Complete Costume Dictionary Elizabeth J. Lewandowski The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2011 Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2011 by Elizabeth J. Lewandowski Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations created by Elizabeth and Dan Lewandowski. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewandowski, Elizabeth J., 1960– The complete costume dictionary / Elizabeth J. Lewandowski ; illustrations by Dan Lewandowski. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8108-4004-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7785-6 (ebook) 1. Clothing and dress—Dictionaries. I. Title. GT507.L49 2011 391.003—dc22 2010051944 ϱ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America For Dan. Without him, I would be a lesser person. It is the fate of those who toil at the lower employments of life, to be rather driven by the fear of evil, than attracted by the prospect of good; to be exposed to censure, without hope of praise; to be disgraced by miscarriage or punished for neglect, where success would have been without applause and diligence without reward. -

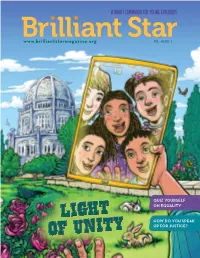

The Light of Unity

, , A BAHaA BAHa` i ` COM` i ` COMPANIONPANION FOR FOR YOUNG YOUNG EXPLORE EXPLORERs Rs wwwww.brilliantstarmagazine.w.brilliantstarmagazine.ororg g VOLV. 48,OL. N48O . NO.2 2 QUIZ YOURSELF THELIGHT LIGHT ON EQUALITY HOW DO YOU SPEAK OFOF UNITYUNITY UP FOR JUSTICE? tt tt BAHÁ’Í NATIONAL CENTER 1233 Central Street, Evanston, Illinois 60201 U.S. 847.853.2354 [email protected] WHAT’S INSIDE Subscriptions: 1.800.999.9019 www.brilliantstarmagazine.org Published by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States FAVORITE FEATURES Amethel Parel-Sewell EDITOR/CREATIVE DIRECTOR C. Aaron Kreader DESIGNER/ILLUSTRATOR Bahá’u’lláh’s Life: Mission of Peace am4 He faced prejudice with faith and courage. Amy Renshaw SENIOR EDITOR Susan Engle ASSOCIATE EDITOR Annie Reneau ASSISTANT EDITOR Nur’s Nook Foad Ghorbani PRODUCTION ASSISTANT 6 Make a string of stars to celebrate diversity. MANY THANKS TO OUR CONTRIBUTORS: Amia Allmart • Brian Beasley • Haley Berkowitz Lisa Blecker • Dr. Robert Bullard • Johnny Cornyn Maya’s Mysteries Francisco Cotto • Darlene Gait • Andrea Hope Nadia Khazei • Lyla Kitchens • Danny Lapidus 10 There may be 100 million species on Earth! Jhian Mahboubi • Doug Marshall • Jim Neeb Eliana Paik • Lucia Pane • Kai Parel-Sewell Paz Parel-Sewell • Layli Phillips • Donna Price We Are One Dr. Stephen Scotti • Haley-Grace Wu • Arshan Lee Yeganegi 11 Explore and care for the place we all call home. ART AND PHOTO CREDITS Original illustrations by C. Aaron Kreader, unless noted By Lisa Blecker: Photos for pp. 6-7; Watercolor for p. 10; Radiant Stars Inking and watercolor for p. -

Bulgaria About This Guide

Expeditionary Culture Field Guide Varna Veliko Tarnovo Sofia Plovdiv Bulgaria About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: Souvenir vendor in the old part of Plovdiv, Bulgaria, courtesy of CultureGrams, ProQuest). The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Eastern Europe. Bulgaria Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Bulgarian society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre-deployment training (Photo: USAF and Bulgarian senior NCOs discuss enlisted force development concerns). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at http://culture.af.mil/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

![Enotes WW1 Turkish Headgear Flaherty 7JU[...]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0830/enotes-ww1-turkish-headgear-flaherty-7ju-3050830.webp)

Enotes WW1 Turkish Headgear Flaherty 7JU[...]

eNOTES WW1 Turkish Headgear Dr Chris Flaherty Updated Research Notes 7 June 2012 www.ottoman-uniforms.com eNOTES WW1 Turkish Headgear Dr Chris Flaherty: Updated Research Notes 7 June 2012 INTRODUCTION This updated research note: ‘WW1 Turkish Headgear’, attempts to bring together the available information, pictures and articles producing a comprehensive outline of the all types of headgear, covers and insignia used during WW1 by the Ottoman Imperial Army and Imperial Ottoman Navy1. Fundamentally, this study shows that only a limited range of headgear was actually used. These are: 1 1876 till 1908 Imperial Army Headgear 2 1876 Helmet of the Firemen Regiment 3 Post-1909 Imperial Army Officer’s Kabalak 4 Post-1914 Officer’s Sunhat 5 Post-1908 Imperial Army Soldier’s Kalpak 6 Post-1913 Imperial Army Soldier’s Kabalak 7 Post-1916 Imperial Army Bashlik 8 Post-1909 Imperial Army Officer’s Kalpak 9 Covers and Insignia 10 Imperial Ottoman Navy Officers’ Caps 11 Imperial Ottoman Navy Sailors’ Caps 12 Yildirim Army Group Steel Helmet 13 Fakes 1. 1876 TILL 1908 IMPERIAL ARMY HEADGEAR In 1247 (1832), a decree of Sultan Mahmud II declared the Fez to be the Ottoman national headdress. To be worn by civilians and military alike. Till 1909, Imperial Army and Navy uniforms did not include provision for headdress, till introduction of the M1909 kalpak (for the Army). Example 1 (Below): However, around 1880s the Ottoman Dragoons and Field Artillery adopted the lambwool cap (which later developed into the M1909 kalpak), which was similar to the Russian cossacks’ fleece cap. It should be noted that from 1876, the Ottoman’s Karapapak tribal cavalry (who emigrated from Azerbaijan, in the 1820s) wore the traditional Russian cossacks’ uniform, and are the likely source for this introduction. -

Mustafa Kemal, Cinema and Turkey: the Early Years (1919-1923)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Performing modernity: Atatürk on film (1919-1938) Dinç, E. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Dinç, E. (2016). Performing modernity: Atatürk on film (1919-1938). General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 Chapter 2 Mustafa Kemal, Cinema and Turkey: The Early Years (1919-1923) The establishment of the Army Film Shooting Center described in the previous chapter shows the Ankara government’s investment in the medium of film. Moreover, it demonstrates their leader Mustafa Kemal’s particular interest in cinema. Film footage from this period featuring Mustafa Kemal suggests that he had particular ideas about how to employ film to create a strong public image in order to influence public opinion with regard to the national struggle. -

Real and Perceived Islamophobia in Bishkek

Policy Brief Based on the results of the research work conducted within the framework of International Alert’s project “Constructive Dialogues Project is financed by on Religion and Democracy” funded by the European Union the European Union Real and perceived Islamophobia in Bishkek Urmat Kaleev, Izaura Maseitova Mentor: Emil Nasritdinov ing religiosity and Islamic practices in the sovereign Kyrgyzstan. Previ- ous research1 indicates that one third of instances of social aggression Resume in the country is based on Islamophobia This research explores the phenome- and that Islamophobia leads to social di- non of Islamophobia – negative attitude vision, religious conflicts, family break- towards Islam and Muslims in Bishkek, ups, marginalization of a practicing the capital of Kyrgyzstan. The research Muslim community and favorable ground work was conducted among the ordinary for the growth of radical ideology. So population of Bishkek and among the far, the post-Soviet Islamophobia in Kyr- representatives of secular and Muslim gyzstan was studied only in the media communities. The research shows that space. This research aimed to assess Islamophobia in Bishkek has a latent the character and the scale of Islam- character; there are strong Islamopho- ophobia on the streets of Bishkek, the bic sentiments, but they rarely manifest capital city, which has a more ethnically themselves in real actions. Research and religiously diverse population than identified five main factors, which in- the rest of the country. crease Islamophobia: (1) Islamic visual images, (2) demographic factors (age, Methodology ethnicity and gender), (3) place of res- The research combined quantitative and idence, (4) alleged Islamic challenge of qualitative methods.