Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Checklist

Mountains and Rivers: Scenic Views of Japan, July 10, 2009-November 1, 2009 The landscape has long been an important part of Japanese art and literature. It was first celebrated in poetry, where invoking the name of a famous location, or meisho, was meant to summon a certain feeling. Later, paintings of these same locations would bring to mind their well-known poetic and literary history. Together, the poems and imagery comprised a canon of place and sentiment, as the same meisho were rendered again and again. During the Edo period (1603–1868) the landscape genre, initially available only to the elite, spread to the medium of woodblock printing, the art of commoner culture. In the 19th century, when most of the works in this exhibition were made, several factors led to the rise of the landscape genre in woodblock prints. Up to this time, the staples of the woodblock print medium had been images of beautiful courtesans and handsome kabuki theater actors. First among these factors was the rising popularity of domestic travel. The development of a system of major roads allowed many people to travel for both business and pleasure. Woodblock prints of locations along these travel routes could function as souvenirs for those who made the trip or as fantasy for those who could not. Rather than evoking a poetic past, these images of meisho were meant to tantalize viewers into imagining romantic far-off places. Another factor in the growth of the genre was the skill of two particular woodblock print artists— Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) (whose works are heavily represented here). -

Osaka Train Route Map Lastupdate May.22.2021 Kanmaki Minase Takatsuki Tokaido(Kyoto) Line Y E

Shimamoto X Osaka Train Route map LastUpdate May.22.2021 Kanmaki Minase Takatsuki Tokaido(Kyoto) Line Y e n Saitonishi i Z Hankyu Minoo Line L o Settsutonda Takatsukishi t i Minoo a Toyokawa Tonda Kuzuha S A l i Hankyu-Takarazuka Line a JRSojiji r o n O Makiochi o Handaibyoinmae Gotenyama m Ikeda Sakurai a Sojiji Makino k a IshibashiHandaimae Kitasenri s Koenhigashiguchi Ibaraki Ibarakishi Hirakatashi O ShibaharaHandaimae Shoji Unobe Hirakatakoen Miyanosaka OsakaMonorail Line Hotarugaike Senrichuo Yamada BanpakuKinenKoen Minamiibaraki Hoshigaoka B Momoyamadai Minamisenri Senrioka Kozenji e n i L Osakakuko Toyonaka Sawaragi Muranno Nagao o n e a t Ryokochikoen n i a L K i Okamachi r Senriyama Kishibe Shojaku Settsushi Settsu Korien Kozu Fujisaka n n a e e h i n S i e e L n u K i y o L Sone Kandaimae e Katanoshi Tsuda k e k n n o i e u t a L y r o k H r y n a Osaka International a K k e Toyotsu h Kawachinomori u a n i i u u s Airport(ITM) e Hankyu Takarazuka Line y L o t K k l a i t n t a i a r K c Suita H o Hoshida Kawachiiwafune c n Tokaido(Kyoto) Line o e Hattoritenjin Aikawa M Minamisettsu Neyagawashi Kisaichi e a f k f Suita Itakano a s e O e Esaka MinamiSuita Neyagawakoen r r Zuiko4 P P N Shonai Kamishinjo Sonoda Higashiyodogawa Shimoshinjo Kayashima o o Shinobugaoka Dainichi t g Tokaido-Shinkansen R Imazatosuji Line o o Higashimikuni Daidotoyosato Moriguchi Owada y y Mikuni Awaji Taishibashiimaichi K Kashima Kanzakigawa Moriguchishi H Kadomashi P JRAwaji Nishisanso Furukawabashi ShinOsaka JR Osakahigashi Line Q Sozenji Senbayashiomiya -

Lions Club Name District Recognition

LIONS CLUB NAME DISTRICT RECOGNITION AGEO District 330 C Model Club AICHI EMERALD District 334 A Model Club AICHI GRACE District 334 A Model Club AICHI HIMAWARI District 334 A Model Club AICHI SAKURA District 334 A Model Club AIZU SHIOKAWA YUGAWA District 332 D Model Club AIZU WAKAMATSU KAKUJO District 332 D Model Club AIZUBANGE District 332 D Model Club ANDONG District 356 E Model Club ANDONG SONGJUK District 356 E Model Club ANJYO District 334 A Model Club ANSAN JOONGANG District 354 B Model Club ANSUNG NUNGKOOL District 354 B Model Club ANYANG INDUK District 354 B Model Club AOMORI CHUO District 332 A Model Club AOMORI HAKKO District 332 A Model Club AOMORI JOMON District 332 A Model Club AOMORI MAHOROBA District 332 A Model Club AOMORI NEBUTA District 332 A Model Club ARAO District 337 E Model Club ASAHIKAWA District 331 B Model Club ASAHIKAWA HIGASHI District 331 B Model Club ASAHIKAWA NANAKAMADO District 331 B Model Club ASAHIKAWA TAISETSU District 331 B Model Club ASAKA District 330 C Model Club ASAKURA District 337 A Model Club ASHIKAGA District 333 B Model Club ASHIKAGA MINAMI District 333 B Model Club ASHIKAGA NISHI District 333 B Model Club ASHIRO District 332 B Model Club ASHIYA District 335 A Model Club ASHIYA HARMONY District 335 A Model Club ASO District 337 E Model Club ATSUGI MULBERRY District 330 B Model Club AYASE District 330 B Model Club BAIK SONG District 354 H Model Club BANGKOK PRAMAHANAKORN 2018 District 310 C Model Club BAYAN BARU District 308 B2 Model Club BIZEN District 336 B Model Club BUCHEON BOKSAGOL District -

Die Riten Des Yoshida Shinto

KAPITEL 5 Die Riten des Yoshida Shinto Das Ritualwesen war das am eifersüchtigsten gehütete Geheimnis des Yoshida Shinto, sein wichtigstes Kapital. Nur Auserwählte durften an Yoshida Riten teilhaben oder gar so weit eingeweiht werden, daß sie selbst in der Lage waren, einen Ritus abzuhalten. Diese zentrale Be- deutung hatten die Riten sicher auch schon für Kanetomos Vorfah- ren. Es ist anzunehmen, daß die Urabe, abgesehen von ihren offizi- ellen priesterlichen Aufgaben, wie sie z.B. in den Engi-shiki festgelegt sind, bereits als ietsukasa bei diversen adeligen Familien private Riten vollzogen, die sie natürlich so weit als möglich geheim halten muß- ten, um ihre priesterliche Monopolstellung halten und erblich weiter- geben zu können. Ein Austausch von geheimen, Glück, Wohlstand oder Schutz vor Krankheiten versprechenden Zeremonien gegen ge- sellschaftliche Anerkennung und materielle Privilegien zwischen den Urabe und der höheren Hofaristokratie fand sicher schon in der späten Heian-Zeit statt, wurde allerdings in der Kamakura Zeit, als das offizielle Hofzeremoniell immer stärker reduziert wurde, für den Bestand der Familie umso notwendiger. Dieser Austausch verlief offenbar über lange Zeit in sehr genau festgelegten Bahnen: Eine Handvoll mächtiger Familien, alle aus dem Stammhaus Fujiwara, dürften die einzigen gewesen sein, die in den Genuß von privaten Urabe-Riten gelangen konnten. Bis weit in die Muromachi-Zeit hin- ein existierte die Spitze der Hofgesellschaft als einziger Orientie- rungspunkt der Priesterfamilie. Mit dem Ōnin-Krieg wurde aber auch diese Grundlage in Frage gestellt, da die Mentoren der Familie selbst zu Bedürftigen wurden. Selbst der große Ichijō Kaneyoshi mußte in dieser Zeit sein Über- leben durch Anbieten seines Wissens und seiner Schriften an mächti- ge Kriegsherren wie z.B. -

Publisbing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: the Case of the Edo Publisher Tsutaya Jqzaburô (1751-97)

Publisbing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: The Case of the Edo Publisher Tsutaya JQzaburô (1751-97) Yu Chang A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 0 Copyright by Yu Chang 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliogtaphic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingtm Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OnawaOFJ KlAW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence diowing the exclusive permettant à la National Librq of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Publishing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: The Case of the Edo Pubüsher Tsutaya Jûzaburô (1750-97) Master of Arts, March 1997 Yu Chang Department of East Asian Studies During the ideologicai program of the Senior Councillor Mitsudaira Sadanobu of the Tokugawa bah@[ governrnent, Tsutaya JÛzaburÔ's aggressive publishing venture found itseif on a collision course with Sadanobu's book censorship policy. -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

Walking Japan

Walking Japan 11 Days Walking Japan This enchanting journey through Japan combines stunning hiking with timeless tradition. Beginning in the old imperial city of Kyoto and ending in modern Tokyo, our itinerary follows the Nakasendo, a network of ancient trade routes once used to travel from Kyoto to the provincial towns of the Kiso Valley. By way of temples, shrines, and hamlets, you'll take in ethereal landscapes of lush gardens, misty forests and possibly the bloom of cherry blossoms. Along the way, enjoy generous Japanese hospitality in a shukubo (temple lodging) and family-run inns, and the contrasts between old and new in this magical land. Details Testimonials Arrive: Kyoto, Japan "A finely tuned and brilliantly led trip that gives the traveler a great take on Depart: Tokyo, Japan Japanese culture." John W. Duration: 11 Days Group Size: 5-12 Guests "Our three-generation family had a wonderful experience hiking village to Minimum Age: 12 Years Old village on the Nakasendo Trail with MT Sobek." Activity Level: Level 3 Mary and David O. REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 MT Sobek's immersive Walking Our itinerary has been crafted Walking Japan is an MT Sobek Japan itinerary offers you the for personal achievement, classic that we've run for over chance to explore idyllic landscapes allowing you to carry nothing 10 years. It is the perfect way on foot with expert local guides. but a daypack as we transport to get to the heart of Japan. your belongings to each inn. ACTIVITIES LODGING CLIMATE Moderately paced hikes up Enjoy stays in traditional ryokans Spring and fall temperatures to 4-9 miles a day on paved (inns) — many with onsen (hot range from 50°F to the and dirt trails, plus cultural springs) — and comfortable high 70°'s F. -

Essentials for Living in Osaka (English)

~Guidebook for Foreign Residents~ Essentials for Living in Osaka (English) Osaka Foundation of International Exchange October 2018 Revised Edition Essentials for Living in Osaka Table of Contents Index by Category ⅠEmergency Measures ・・・1 1. Emergency Telephone Numbers 2. In Case of Emergency (Fire, Sudden Sickness and Crime) Fire; Sudden Illness & Injury etc.; Crime Victim, Phoning for Assistance; Body Parts 3. Precautions against Natural Disasters Typhoons, Earthquakes, Collecting Information on Natural Disasters; Evacuation Areas ⅡHealth and Medical Care ・・・8 1. Medical Care (Use of medical institutions) Medical Care in Japan; Medical Institutions; Hospital Admission; Hospitals with Foreign Language Speaking Staff; Injury or Sickness at Night or during Holidays 2. Medical Insurance (National Health Insurance, Nursing Care Insurance and others) Medical Insurance in Japan; National Health Insurance; Latter-Stage Elderly Healthcare Insurance System; Nursing Care Insurance (Kaigo Hoken) 3. Health Management Public Health Center (Hokenjo); Municipal Medical Health Center (Medical Care and Health) Ⅲ Daily Life and Housing ・・・16 1. Looking for Housing Applying for Prefectural Housing; Other Public Housing; Looking for Private Housing 2. Moving Out and Leaving Japan Procedures at Your Old Residence Before Moving; After Moving into a New Residence; When You Leave Japan 3. Water Service Application; Water Rates; Points of Concern in Winter 4. Electricity Electricity in Japan; Application for Electrical Service; Payment; Notice of the Amount of Electricity Used 5. Gas Types of Gas; Gas Leakage; Gas Usage Notice and Payment Receipt 6. Garbage Garbage Disposal; How to Dispose of Other Types of Garbage 7. Daily Life Manners for Living in Japan; Consumer Affairs 8. When You Face Problems in Life Ⅳ Residency Management System・Basic Resident Registration System for Foreign Nationals・Marriage・Divorce ・・・27 1. -

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

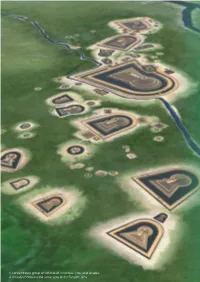

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

ABOUT SHIGA ACCESS to SHIGA BIWAICHI OMI

ALL MAP FREE SEP- NOV 2018 vol.1 Scan here for the maps 9 SEPTEMBER 10 OCTOBER 11 NOVEMBER BIWAKO BIENNALE 2018 TUKUROHI, ATSUSHI FUJIWARA, KIZASHI ~BEYOND~ PHOTOGRAPH EXHIBITION TREE CANOPY TRAIL OPENING Ancient townscapes and contem- It is the distance itself makes us A new outdoor exhibit has porary art meet in the old town of try to connect. The Shiga-born opened at the Lake Biwa Omihachiman for this international photographer Atsushi Fujiwara Museum. The Tree Canopy art festival. Around 77 groups of has been continuing to chase Trail lets visitors walk high artists from around the world will such dreams of humans. His among the treetops, granting exhibit their works in buildings latest work, Semimaru, and the an unparalleled view of Lake filled with history, such as houses from the Edo period three preceding collections will be on display. Enjoy his Biwa, and giving visitors the chance to get up close and (1603-1867), a former sake brewery, and more. journey for connection. personal with Japan’s largest lake and the surrounding forest. The opening of this new interactive space in DATE From Sat., September 15th to Sun., November 11th *Closed Tue. DATE From Sat., October 6th to Sun., November 4th nature creates a new symbol for the museum. TIME 10am-5pm TIME 9am-4:30pm CAS T L E PLACE Old city area of Omi Hachiman (12 Nagahara-cho Naka, Omi Hachiman, PLACE MIIDERA-Temple Kannon-do Shoin hall (246 Onjoji-cho, Otsu, Shiga) Shiga and its vicinities) ADMISSION Free (Separate fee for entering MIIDERA-Temple: ¥600, Junior DATE Opens on Sat.,