German Post-Socialist Memory Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Thüringer CDU in Der SBZ/DDR – Blockpartei Mit Eigeninteresse

Bertram Triebel Die Thüringer CDU in der SBZ/DDR – Blockpartei mit Eigeninteresse Bertram Triebel Die Thüringer CDU in der SBZ/DDR Blockpartei mit Eigeninteresse Herausgegeben im Auftrag der Unabhängigen Historischen Kommission zur Geschichte der CDU in Thüringen und in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl von 1945 bis 1990 von Jörg Ganzenmüller und Hermann Wentker Herausgegeben im Auftrag der Unabhängigen Historischen Kommission zur Geschichte der CDU in Thüringen und in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl von 1945 bis 1990 von Jörg Ganzenmüller und Hermann Wentker Das Werk ist in allen seinen Teilen urheberrechtlich geschützt. Weiterverwertungen sind ohne Zustimmung der Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung e.V. unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung in und Verarbeitung durch elektronische Systeme. © 2019, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin/Berlin Umschlaggestaltung: Hans Dung Satz: CMS der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Druck: Kern GmbH, Bexbach Printed in Germany. Gedruckt mit finanzieller Unterstützung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. ISBN: 978-3-95721-569-7 Inhaltsverzeichnis Geleitworte . 7 Vorwort . 13 Einleitung . 15 I. Gründungs- und Transformationsjahre: Die Thüringer CDU in der SBZ und frühen DDR (1945–1961) 1. Die Gründung der CDU in Thüringen . 23 2. Wandlung und Auflösung des Landesverbandes . 32 3. Im Bann der Transformation: Die CDU in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl bis 1961 . 46 II. Die CDU in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl – Eine Blockpartei im Staatssozialismus (1961–1985) 1. Die Organisation der CDU . 59 1.1. Funktion und Parteikultur der CDU . 60 1.2. Der Apparat der CDU in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl . 62 1.3. -

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Für Freiheit Und Demokratie

Bernd Eisenfeld/Rainer Eppelmann/ Karl Wilhelm Fricke/Peter Maser Für Freiheit und Demokratie 40 Jahre Widerstand in der SBZ/DDR Wissenschaftliche Dienste Archiv für Christlich-Demokratische Politik 2 Bernd Eisenfeld/Rainer Eppelmann/Karl Wilhelm Fricke/Peter Maser Für Freiheit und Demokratie 40 Jahre Widerstand in der SBZ/DDR 3 ISBN 3-931575-99-3 Herausgeber: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Wissenschaftliche Dienste 4 INHALT Vorwort ... 7 Karl Wilhelm Fricke: Widerstand und politische Verfolgung in der DDR ... 9 Peter Maser: Die Rolle der Kirchen für die Opposition ... 20 Bernd Eisenfeld: Stasi-Methoden in den achtziger Jahren bei der Bekämpfung widerständiger Erscheinungen ... 33 Rainer Eppelmann: Stiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur ... 44 5 6 Vorwort Seit 1991 veranstaltet das Archiv für Christlich-Demokratische Politik der Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung jährlich eine Tagung zum Thema ”Widerstand und Verfolgung in der SBZ/DDR. Das achte ”Buchenwald-Gespräch” fand Ende Oktober 1998 in Berlin in Verbindung mit der Gedenkstätte Hohenschönhausen statt. Hohenschönhausen ist ein authentischer Ort der kommunistischen Willkürjustiz und politischen Strafverfolgung. Die Gebäude der ehemaligen Großküche wurden nach Kriegsende von der sowjetischen Besatzungsmacht als Internierungslager für NSDAP- Mitglieder und NS-Verdächtige genutzt. Nach Auflösung des ”Speziallagers Nr. 3” diente Hohenschönhausen als zentrales sowjetisches Untersuchungsgefängnis für politisch- ideologische Gegner. 1950 richtete dort das Ministerium für Staatssicherheit eine zentrale Untersuchungshaftanstalt für politische Häftlinge ein. Der Rundgang unter Führung ehemaliger Häftlinge ließ die bedrückende Atmosphäre, Isolation und seelische Zermürbung lebendig werden, der die Insassen ausgesetzt waren. Im Mittelpunkt der Vorträge stand die Verfolgung der Regimegegner durch die SED in den fünfziger, siebziger und achtziger Jahren. Eine Auswahl der Beiträge ist in dieser Broschüre abgedruckt. -

1993 Friedrich Schorlemmer FRIEDENSPREIS DES DEUTSCHEN BUCHHANDELS

1993 Friedrich Schorlemmer FRIEDENSPREIS DES DEUTSCHEN BUCHHANDELS Richard von Weizsäcker _________________________________ Laudatio Der Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhan- ist eine elementare Gefahr für den Frieden. So dels wird in diesem Jahr an einen im deutschen unendlich wichtig und schwer es ist, immer von Gemeindewesen verwurzelten Pfarrer verliehen. neuem Toleranz zu lernen und zu üben, so bleibt Das hat die Paulskirche bisher noch nicht erlebt. sie doch allzuoft passiv und gleichgültig gegen- Ich freue mich darüber und erlaube mir zunächst über Not und Leid und Ungerechtigkeit. einige allgemeine Worte der Begründung. Ein Wall zwischen Kultur und Politik? Was In der ruhmreichen Geschichte des Frieden- sollte er helfen? Kultur lebt ja nicht abgeschottet spreises war schon deutlich von dem »stark be- gegen die harten Tatsachen, Interessen und festigten Wall zwischen Kultur und Religion« Kämpfe des Lebens. Sie ist kein Vorbehaltsgut die Rede (Paul Tillich), von der Abgrenzung für ein paar Eingeweihte, sondern sie ist die zwischen Glauben, Politik und literarischer Fülle unserer menschlichen Lebensweise mit Kunst. Im Zeichen des Friedens, dem der Preis allen ihren Unterschieden. Sie ist damit die we- gilt, ist dies eher merkwürdig, auch wenn man sentliche Substanz, um die es in der Politik ge- Gründe dafür finden kann. - Unsere heutige sä- hen sollte. Wer die Bedeutung begreift, die der kularisierte Gesellschaft bekennt sich mit ihrer Nachbar seiner Kultur zumißt, lernt ihn und lernt politischen Verfassung zum Pluralismus und zur zugleich sich selbst besser verstehen. Er beginnt, weltanschaulichen Neutralität. Es geht um die ihn zu achten, und hört auf, in ihm einen Fremd- Regeln des Zusammenlebens, nicht um die Su- ling oder gar Feind zu sehen. -

Berlin, Den 17.12.2002 Jürgen-Fuchs-Straße in Erfurt Am

Berlin, den 17.12.2002 Jürgen-Fuchs-Straße in Erfurt Am 20. Dezember 02, anläßlich des 52. Geburtstags des Dichters, wird die Straße am Landtag in Erfurt in Jürgen-Fuchs-Straße benannt. Die Stadt Erfurt und der Landtag des Landes Thüringen ehren mit der Benennung einen Poeten, der mit seinen intensiven, leisen Gedichten die Nöte einer DDR-Jugend ausdrückte, die sich in den Zwängen des totalen Anspruches der SED auf die Menschen selbst zu behaupten versuchte. Seine akribische Beobachtung wertete die Realität ohne den erhobenen Zeigefinger des Moralisten. Die real existierenden Sozialisten sperrten ihn dafür ins Gefängnis und schoben ihn vor 25 Jahren in den Westen ab. Der so in eine neue Welt Geworfene konnte nun in seinem Beruf als Psychologe arbeiten und baute gemeinsam mit seiner Frau den "Treffpunkt Waldstraße" im Berliner Problembezirk Moabit auf, einen Heimatort für Jugendliche und Kinder aus schwierigen sozialen Verhältnissen.Jürgen Fuchs' literarisches Werk blieb nicht bei der Beschreibung des sozialistischen Totalitarismus stehen, sondern lotete die Möglichkeiten des Menschseins darin aus. In seiner Geradlinigkeit und seinem unbestechlichen Urteil achtete Fuchs darauf, daß die Aufarbeitung des SED-Unrechts nicht abstrakt blieb, sondern den Menschen in ihrer konkreten Situation gerecht wurde. Dafür ist ihm das Bürgerbüro e.V., zu dessen Gründern er gehörte, dankbar und verpflichtet. Der Weg in den Thüringer Landtag führt zukünftig über eine Straße der Sensibilität für die Nöte der Mitmenschen und des Engagements für die Menschenrechte. Dr. Ehrhart Neubert, amt. Vorsitzender Ralf Hirsch, Vorstand Presseerklärung vom 22.10.2002 JÖRN MOTHES: Kein Abstand zur Diktatur Ringstorff und Holter haben in ihrer Koalitionsvereinbarung die Auflösung der Behörde des Landesbeauftragten des Landes Mecklenburg-Vorpommern für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen DDR beschlossen. -

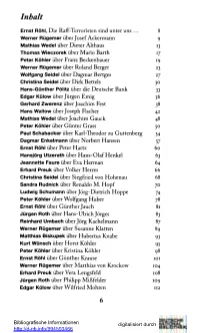

Inhalt Ernst Röhl, Die Raff-Terroristen Sind Unter Uns

Inhalt Ernst Röhl, Die Raff-Terroristen sind unter uns ... 8 Werner Rügemer über Josef Ackermann 9 Mathias Wedel über Dieter Althaus 13 Thomas Wieczorek über Mario Barth 17 Peter Köhler über Franz Beckenbauer 19 Werner Rügemer über Roland Berger 23 Wolfgang Seidel über Dagmar Bertges 27 Christina Seidel über Dirk Bettels 30 Hans-Günther Pölitz über die Deutsche Bank 33 Edgar Külow über Jürgen Emig 36 Gerhard Zwerenz über Joachim Fest 38 Hans Wallow über Joseph Fischer 42 Mathias Wedel über Joachim Gauck 48 Peter Köhler über Günter Grass 50 Paul Schabacker über Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg 54 Dagmar Enkelmann über Norbert Hansen 57 Ernst Röhl über Peter Hartz 60 Hansjörg Utzerath über Hans-Olaf Henkel 63 Jeannette Faure über Eva Herman 64 Erhard Preuk über Volker Herres 66 Christina Seidel über Siegfried von Hohenau 68 Sandra Rudnick über Renaldo M. Hopf 70 Ludwig Schumann über Jörg-Dietrich Hoppe 74 Peter Köhler über Wolfgang Huber 78 Ernst Röhl über Günther Jauch 81 Jürgen Roth über Hans-Ulrich Jorges 83 Reinhard Limbach über Jörg Kachelmann 87 Werner Rügemer über Susanne Klatten 89 Matthias Biskupek über Hubertus Knabe 93 Kurt Wünsch über Horst Köhler 95 Peter Köhler über Kristina Köhler 98 Ernst Röhl über Günther Krause 101 Werner Rügemer über Matthias von Krockow 104 Erhard Preuk über Vera Lengsfeld 108 Jürgen Roth über Philipp Mißfelder 109 Edgar Külow über Wilfried Mohren 112 Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/994503466 Paul Schabacker über Franz Müntefering 115 Christoph Hofrichter über Günther Oettinger 120 Reinhard Limbach über Hubertus Pellengahr 122 Stephan Krull über Ferdinand Piëch 123 Ernst Röhl über Heinrich von Pierer 127 Paul Schabacker über Papst Benedikt XVI. -

Wolfgang Thierse – Günter Nooke – Florian Mausbach – Günter Jeschonnek

Wolfgang Thierse – Günter Nooke – Florian Mausbach – Günter Jeschonnek Berlin, im November 2016 An die Mitglieder des Kultur- und Medienausschusses des Deutschen Bundestags Mitglieder des Haushaltsausschusses des Deutschen Bundestages Sehr geehrter Herr/Frau N.N., der Deutsche Bundestag hat am 9. November 2007 beschlossen, ein Freiheits- und Einheitsdenkmal zu errichten und entschied 2008 in einem weiteren Beschluss die Schlossfreiheit als seinen Standort. Es soll an die friedliche Revolution von 1989 und die Wiedergewinnung der staatlichen Einheit erinnern. 2011 ging aus zwei internationalen Wettbewerben mit 920 Einreichungen der Entwurf „Bürger in Bewegung“ als Sieger hervor. Überraschend hatte der Haushaltsausschuss am 13. April 2016 die Bundesregierung aufgefordert, das mittlerweile TÜV-zertifizierte und baureife Freiheits- und Einheitsdenkmals an historischer Stelle vor dem Berliner Schloss „nicht weiter zu verfolgen“. Begründet hat er diesen in nicht öffentlicher Sitzung gefassten Beschluss mit einer angeblichen „Kostenexplosion“. Diese Entscheidung kam ohne vorherige öffentliche Diskussion zustande: Weder wirkte der dafür fachlich zuständige Kulturausschuss mit, noch hatte sich das Plenum des Deutschen Bundestages damit erneut befasst. Nach öffentlichen Interventionen von verschiedener Seite stellte Bundestagspräsident Lammert am 29. September 2016 im Ältestenrat fest, dass der Beschluss eines Ausschusses keinen Plenarbeschluss aufheben kann und hat die Fraktionen aufgefordert, sich Gedanken über das weitere Vorgehen zu machen. -

Interview with Rainer Eppelmann (MP/CDU), Chairman of the Enquete

Volume 10. One Germany in Europe, 1989 – 2009 Rainer Eppelmann talks about the Enquete Commission on the SED Dictatorship (May 3, 1992) In an interview with the national news radio station Deutschlandfunk, the chairman of the Enquete Commission, former East German dissident Rainer Eppelmann, discusses the challenge of engaging in a public discussion of the history of the East German dictatorship. He also addresses the ambivalent role of the Protestant church and the importance of maintaining open access to Stasi files. Interview with Rainer Eppelmann (Bundestag Member/CDU), Chairman of the Enquete Commission for the “Reappraisal of the History and Consequenes of the SED Dictatorship” Deutschlandfunk: Mr. Eppelmann, forgive and forget are not the worst Christian virtues. You are now heading the Enquete Commission of the Bundestag on the reappraisal of the SED dictatorship? Don‟t people have other, very different worries? Eppelmann: People do have other worries. But the question “What was going on during these last forty years, especially with this [Ministry of] State Security?” has been filling the first, second, and third pages of all the newspapers since the beginning of this year. There‟s hardly a newscast, hardly a television broadcast on current issues in Germany without a news item on this topic. That‟s to say, the question of what really happened there, what kind of pressure was exerted on me by this State Security, either directly or through the school, the workplace, the sports club, the cultural association, or the writers‟ association – that‟s a question that preoccupies many people in East Germany. Fortunately not all of them. -

Kleine Anfrage Der Abgeordneten Bodo Ramelow, Dr

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 16/718 16. Wahlperiode 16. 02. 2006 Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Bodo Ramelow, Dr. Dagmar Enkelmann, Dr. Gesine Lötzsch, Dr. Barbara Höll, Dr. Dietmar Bartsch, Michael Leutert, Roland Claus, Katrin Kunert und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. Perspektiven der Länderfinanzen im Rahmen der Föderalismusreform und des EU-Finanzkompromisses Seit dem Amtsantritt der Bundesregierung sind mit der angestrebten Föderalis- musreform, den steuerpolitischen Beschlüssen der Koalitionsvertrag sowie dem EU-Finanzkompromiss Vereinbarungen getroffen worden, die die Finanzen der Länder unmittelbar berühren. Wir fragen die Bundesregierung: A. Entwicklung der Länderfinanzen 2002 bis 2005 1. Wie gestalteten sich die Einnahmen und Ausgaben je Einwohnerin bzw. Ein- wohner sowie die Ausgabe-Einnahme-Relation in den Ländern in den Jahren 2002 bis 2005 (bitte aufschlüsseln nach Land, Jahr sowie Vergleich ost- und westdeutsche Länder und Bund), und wie bewerten die Bundesregierung und der Finanzplanungsrat diese Entwicklung? 2. Wie gestalteten sich die Personalausgaben sowie die Ausgaben für Bau- investitionen je Einwohnerin bzw. Einwohner in den ostdeutschen Ländern in den Jahren 2002 bis 2005 (bitte aufschlüsseln nach Land, Jahr sowie Vergleich ost- und westdeutsche Länder und Bund), und wie bewerten die Bundesregierung und der Finanzplanungsrat diese Entwicklung? 3. Wie gestaltete sich der Schuldenstand in den ostdeutschen Ländern im Ver- gleich zu den westdeutschen Ländern und dem Bund im Zeitraum seit 2002, und wie erklärt bzw. bewertet die Bundesregierung diese Entwicklung? 4. Wie gestaltete sich der Deckungsgrad der Ausgaben der ostdeutschen Län- der im Vergleich zu den westdeutschen Ländern und dem Bund im Zeitraum seit 2002, und wie erklärt bzw. bewertet die Bundesregierung diese Entwick- lung? 5. Wie hoch sind die Kosten der DDR-Sonder- und Zusatzversorgung für die ostdeutschen Länder, und wie sind diese Kosten im föderalen Finanzsystem aufgeteilt (bitte aufschlüsseln)? 6. -

Motion: Europe Is Worth It – for a Green Recovery Rooted in Solidarity and A

German Bundestag Printed paper 19/20564 19th electoral term 30 June 2020 version Preliminary Motion tabled by the Members of the Bundestag Agnieszka Brugger, Anja Hajduk, Dr Franziska Brantner, Sven-Christian Kindler, Dr Frithjof Schmidt, Margarete Bause, Kai Gehring, Uwe Kekeritz, Katja Keul, Dr Tobias Lindner, Omid Nouripour, Cem Özdemir, Claudia Roth, Manuel Sarrazin, Jürgen Trittin, Ottmar von Holtz, Luise Amtsberg, Lisa Badum, Danyal Bayaz, Ekin Deligöz, Katja Dörner, Katharina Dröge, Britta Haßelmann, Steffi Lemke, Claudia Müller, Beate Müller-Gemmeke, Erhard Grundl, Dr Kirsten Kappert-Gonther, Maria Klein-Schmeink, Christian Kühn, Stephan Kühn, Stefan Schmidt, Dr Wolfgang Strengmann-Kuhn, Markus Tressel, Lisa Paus, Tabea Rößner, Corinna Rüffer, Margit Stumpp, Dr Konstantin von Notz, Dr Julia Verlinden, Beate Walter-Rosenheimer, Gerhard Zickenheiner and the Alliance 90/The Greens parliamentary group be to Europe is worth it – for a green recovery rooted in solidarity and a strong 2021- 2027 EU budget the by replaced The Bundestag is requested to adopt the following resolution: I. The German Bundestag notes: A strong European Union (EU) built on solidarity which protects its citizens and our livelihoods is the best investment we can make in our future. Our aim is an EU that also and especially proves its worth during these difficult times of the corona pandemic, that fosters democracy, prosperity, equality and health and that resolutely tackles the challenge of the century that is climate protection. We need an EU that bolsters international cooperation on the world stage and does not abandon the weakest on this earth. proofread This requires an EU capable of taking effective action both internally and externally, it requires greater solidarity on our continent and beyond - because no country can effectively combat the climate crisis on its own, no country can stamp out the pandemic on its own. -

The GDR Opposition Archive

The GDR Opposition Archive in the Robert Havemann Society The GDR Opposition Archive in the Robert Havemann Society holds the largest accessible collection of testaments to the protest against the SED dictatorship. Some 750 linear metres of written material, 180,000 photos, 5,000 videos, 1,000 audio cassettes, original banners and objects from the years 1945 to 1990 all provide impressive evidence that there was always contradiction and resistance in East Germany. The collection forms a counterpoint and an important addition to the version of history presented by the former regime, particularly the Stasi files. Originally emerging from the GDR’s civil rights movement, the archive is now known beyond Germany itself. Enquiries come from all over Europe, the US, Canada, Australia and Korea. Hundreds of research papers, radio and TV programmes, films and exhibitions on the GDR have drawn on sources from the collection. Thus, the GDR Opposition Archive has made a key contribution to our understanding of the communist dictatorship. Testimonials on opposition and resistance against the communist dictatorship The GDR Opposition Archive is run by the Robert Havemann Society. It was founded 26 years ago, on 19 November 1990, by members and supporters of the New Forum group, including prominent GDR opposition figures such as Bärbel Bohley, Jens Reich, Sebastian Pflugbeil and Katja Havemann. To this day, the organisation aims to document the history of opposition and resistance in the GDR and to ensure it is not forgotten. The Robert Havemann Society has been funded entirely on a project basis since its foundation. Its most important funding institutions include the Berlin Commissioner for the Stasi Records and the Federal Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship. -

Gründungsaufruf Des Kuratoriums Für Einen Demokratisch Verfassten Bund Der Länder

Am 16. Juni 1990 hat sich im Reichstag, Berlin, Das Kuratorium ist ein Forum für eine breite das KURATORIUM FÜR EINEN DEMOKRA- öffentliche Verfassungsdiskussion, eine TISCH VERFASSTEN BUND DEUTSCHER LÄN- Verfassunggebende Versammlung und für DER gegründet und folgenden Gründungsauf- eine gesamtdeutsche Verfassung mit Volks- ruf verabschiedet: entscheid. Um diesen Forderungen Nach- „Das KURATORIUM FÜR EINEN DEMOKRA- druck zu verleihen, führen wir eine Unter- TISCH VERFASSTEN BUND DEUTSCHER LÄN- schriftensammlung durch und rufen auf, DER hat sich gebildet, um eine breite öffentliche Ver- sich daran aktiv zu beteiligen. fassungsdiskussion zu fördern, deren Ergebnisse in eine Verfassunggebende Versammlung einmünden sol- „Ich will, daß die Menschen in der B R D und in der len. Auf der Basis des Grundgesetzes für die Bundes- D D R ihr politisches Zusammenleben selbst gestalten republik Deutschland, unter Wahrung der in ihm ent- und darüber in einer Volksabstimmung entscheiden haltenen Grundrechte und unter Berücksichtigung können. Die wichtigsten Weichenstellungen für die des Verfassungsentwurfs des Runden Tisches für die neue deutsche Republik dürfen nicht über die Köpfe DDR, soll eine neue gesamtdeutsche Verfassung aus- der Menschen hinweg getroffen werden. gearbeitet werden. Wir setzen uns dafür ein, daß die Deshalb muß unter Beteiligung der Bürgerinnen und Einberufung einer Verfassunggebenden Versammlung Bürger eine Verfassung ausgearbeitet und ,von dem zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der deutschen Volke in freier Entscheidung beschlossen' Deutschen Demokratischen Republik verbindlich werden (Art. 146 GG). Diese Verfassung darf nicht festgeschrieben und die neue gesamtdeutsche Verfas- hinter das Grundgesetz der Bunderepublik Deutsch- sung von den Bürgerinnen und Bürgern durch Volks- land zurückfallen. Sie bietet vielmehr die Chance, entscheid angenommen wird." (verabschiedet auf der den hinzugekommenen Aufgaben entsprechend, die Gründungssitzung des Kuratoriums am 16.