Association Between Diets and Mild Cognitive Impairment in Adults Aged 50 Years Or Older

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

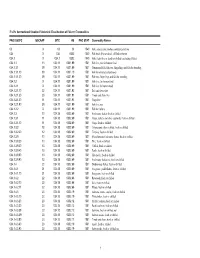

15.8.2014 15,894 Brand Name (In Chinese) 品牌名稱(中文) Product

Generation Date: 15.8.2014 List of Small Volume Exemption Products 已獲小量豁免產品名單 Total Number of SVE products: 15,894 (已獲小量豁免產品總數): Brand Name (in Product Name (in Chinese) Brand Name (in English) Product Name (in English) Exemption End Date Effective Date for Exemption No. Chinese) 產品名稱 (中文) 品牌名稱 (英文) 產品名稱 (英文) (豁免終止日期) Revocation of (豁免編號) 品牌名稱 (中文) Exemption (豁免撤銷生效日期) Nil Nil Nil Sanko Rice Roll with Seaweed 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007124 Nil Nil Nil Sanko Rice Cracker - Castard 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007123 Nil Nil Nil Wonderland Panda - Choco Ball 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007083 Nil Nil Nil Wonderland Candy - Animal Assort 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007082 Nil Nil Nil Asahi Ice Limone 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007081 Nil Nil Nil Asahi Ice Grapefruit 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007079 Nil Nil Nil MARUESU SNACK - WASABI SOY SAUCE TASTE 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007078 Nil Nil Nil MARUESU SNACK - HOKKAIDO CHEESE TASTE 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007072 Nil Nil Nil KASUGAI BEACH SODA CANDY 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007071 Nil Nil Nil Nissin Corn Flakes 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007070 Nil Nil Nil MARUESU SNACK - MAYONNAISE TASTE 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007069 Nil Nil Nil KASUGAI UME AME 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007068 Nil Nil Nil Bonchi Wheat Snack - Seaweed 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007067 Nil Nil Nil Bonchi Wheat Snack - Spicy 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007066 Nil Nil Nil Kasugai Gummy Candy - Muscat Flavor 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007065 Nil Nil Nil Kasugai Gummy Candy - Grape Flavor 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007064 Nil Nil Nil Kasugai Gummy Candy - Peach Flavor 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007063 Nil Nil Nil Bonchi Rice Snack 2015/07/31 N/A 14-007062 Nil Nil Nil Nissin -

Nutrients and Bioactive Potentials of Edible Green and Red Seaweed in Korea K

Sanjeewa et al. Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences (2018) 21:19 https://doi.org/10.1186/s41240-018-0095-y REVIEW Open Access Nutrients and bioactive potentials of edible green and red seaweed in Korea K. K. Asanka Sanjeewa, WonWoo Lee and You-Jin Jeon* Abstract Background: Traditionally, East-Asians (Korea, Japan, and China) utilize seaweeds as a food source and ingredient in traditional medicine. Korea is one of the biggest seaweed producer and consumer in the global trade. Especially, side dishes made from seaweeds are very popular in the traditional Korean cuisines. Seaweeds are popular as fresh vegetable salads and soup or eaten as snacks. Main body: Seaweeds are rich in essential nutrients, minerals, and vitamins as well as a promising source of novel bioactive compounds. The compounds (polysaccharides, polyphenols, and sterols) present in the edible Korean seaweeds possess important bioactive properties such as antioxidant, anti-inflammation, anticancer, anti-diabetic, and anticoagulant properties. Thus, the long-term consumption of seaweed has a potential to reduce the risk of cancer, diabetes, obesity, and inflammation-related complications. However, seaweed consumption is limited to the small population around the globe. Thus, it is important to increase the awareness of the health benefits of seaweeds consumption among the general population. Short conclusion: In the present study, we discussed some popular green and red edible Korean seaweeds and their health-promoting properties. This study might be useful to increase the public awareness of the consumption of seaweed as a food source. Keywords: Edible seaweed, Bioactive, Functional foods Background public awareness, demand for seaweeds and their commer- Seaweeds have been used as human food since ancient times. -

FIC-Prop-65-Notice-Reporter.Pdf

FIC Proposition 65 Food Notice Reporter (Current as of 9/25/2021) A B C D E F G H Date Attorney Alleged Notice General Manufacturer Product of Amended/ Additional Chemical(s) 60 day Notice Link was Case /Company Concern Withdrawn Notice Detected 1 Filed Number Sprouts VeggIe RotInI; Sprouts FruIt & GraIn https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl Sprouts Farmers Cereal Bars; Sprouts 9/24/21 2021-02369 Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Market, Inc. SpInach FettucIne; 02369.pdf Sprouts StraIght Cut 2 Sweet Potato FrIes Sprouts Pasta & VeggIe https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl Sprouts Farmers 9/24/21 2021-02370 Sauce; Sprouts VeggIe Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Market, Inc. 3 Power Bowl 02370.pdf Dawn Anderson, LLC; https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02371 Sprouts Farmers OhI Wholesome Bars Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 4 Market, Inc. 02371.pdf Brad's Raw ChIps, LLC; https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02372 Sprouts Farmers Brad's Raw ChIps Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 5 Market, Inc. 02372.pdf Plant Snacks, LLC; Plant Snacks Vegan https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02373 Sprouts Farmers Cheddar Cassava Root Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 6 Market, Inc. ChIps 02373.pdf Nature's Earthly https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl ChoIce; Global JuIces Nature's Earthly ChoIce 9/24/21 2021-02374 Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- and FruIts, LLC; Great Day Beet Powder 02374.pdf 7 Walmart, Inc. Freeland Foods, LLC; Go Raw OrganIc https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02375 Ralphs Grocery Sprouted Sea Salt Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 8 Company Sunflower Seeds 02375.pdf The CarrIngton Tea https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl CarrIngton Farms Beet 9/24/21 2021-02376 Company, LLC; Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Root Powder 9 Walmart, Inc. -

FAO's International Standard Statistical Classification of Fishery Commodities

FAO's International Standard Statistical Classification of Fishery Commodities FAO ISSCFC ISSCAAP SITC HS FAO STAT Commodity Names 03 X 03 03 1540 Fish, crustaceans, molluscs and preparations 034 X 034 0302 1540 Fish fresh (live or dead), chilled or frozen 034.1 X 034.1 0302 1540 Fish, fresh (live or dead) or chilled (excluding fillets) 034.1.1 13 034.11 0301.99 1501 Fish live, not for human food 034.1.1.1 39 034.11 0301.99 1501 Ornamental fish, fish ova, fingerlings and fish for breeding 034.1.1.1.10 39 034.11 0301.10 1501 Fish for ornamental purposes 034.1.1.1.20 39 034.11 0301.99 1501 Fish ova, fingerlings and fish for breeding 034.1.2 X 034.110301.99 1501 Fish live, for human food 034.1.2.1 X 034.110301.99 1501 Fish live for human food 034.1.2.1.10 22 034.11 0301.92 1501 Eels and elvers live 034.1.2.1.20 23 034.11 0301.91 1501 Trouts and chars live 034.1.2.1.30 11 034.11 0301.93 1501 Carps live 034.1.2.1.90 39 034.11 0301.99 1501 Fish live, nei 034.1.2.2 X 034.110301.99 1501 Fish for culture 034.1.3 10 034.18 0302.69 1501 Freshwater fishes, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.1 11 034.18 0302.69 1501 Carps, barbels and other cyprinids, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.1.10 11 034.18 0302.69 1501 Carps, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.2 12 034.18 0302.69 1501 Tilapias and other cichlids, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.2.20 12 034.18 0302.69 1501 Tilapias, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.9 10 034.18 0302.69 1501 Miscellaneous freshwater fishes, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.9.20 13 034.18 0302.69 1501 Pike, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.9.30 13 034.18 0302.69 1501 Catfish, fresh or -

Dict-En-Fr-Food V3

Dictionnaire Anglais-Français de l’Alimentation English-French Food Dictionary Version 3.0 Pascal Médeville (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) 1 This work is distributed under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Please revise the information below and stay within the limits of the license. 2 Le présent travail est distribué dans le cadre de la licence Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Veuillez lire les informations ci-dessous et respecter les limites imposées. 3 Sigles et abréviations utilisés dans ce dictionnaire : adj. : adjectif agr. : agriculture bot. : botanique ichtyol. : ichtyologie Ind. : Indonésie it. : Italie J : Japon microbiol. : microbiologie œnol. : œnologie p.ex. : par exemple UK : Royaume Uni US : États-Unis d’Amérique vét. : médecine vétérinaire zool. : zoologie Historique des versions/Version history : Date Objet No. de version Déc. 2008 Version initiale 1.0 Juin 2009 Corrections diverses ; Ajout de nouvelles sources ; Ajout de nouvelles 2.0 références bibliographiques Avril 2020 Ajout de nouvelles entrées ; Corrections diverses ; Ajout de nouvelles 3.0 sources ; Ajout de nouvelles references bibliographiques 4 Pour vos traductions anglais-français ou chinois-français dans le domaine de la gastronomie ou de l’agro-alimentaire, veuillez prendre contact avec Pascal Médeville à l’une des adresses suivantes : [email protected] ou [email protected]. For all your food and agrifood translation needs (English to French of Chinese to French), you can contact Pascal Médeville, at [email protected] or [email protected]. Pour toutes vos traductions et besoins de publication assistée par ordinateur en chinois ou d’autres langues asiatiques, n’hésitez pas à faire appel à Pascal Médeville ou à Parallels Translation Office : www.parallels-translation.net. -

Cedar Box Teaching Toolkit

Cedar Box Teaching Toolkit Created by the Muckleshoot Traditional Foods Program with funding from the First Nations Development Institute & the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board NPAIHB Indian Leadership for Indian Health CREATIVE COMMONS NOTICE - 2017 materials This teaching tool was created by Elise Krohn and Valerie Segrest, and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. You are free to share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format — under the following terms: Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. This resource is available through Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board. Posters and the Feeding 7 Generations Recipe Book are also available through www.chatwinbooks.com Table of Contents About the Cedar Box Teaching Toolkit How to Use this Curriculum Introduction From White Cap to White Cap – Cultural Ecosystems by Abe Lloyd and Elise Krohn Feeding 7 Generations by Valerie Segrest and Elise Krohn The Impacts -

Seafood Watch

Farmed Seaweed Image © Monterey Bay Aquarium Worldwide All Production Systems July 28, 2014 Andrea Flynn, Consulting Researcher Disclaimer Seafood Watch® strives to have all Seafood Reports reviewed for accuracy and completeness by external scientists with expertise in ecology, fisheries science and aquaculture. Scientific review, however, does not constitute an endorsement of the Seafood Watch® program or its recommendations on the part of the reviewing scientists. Seafood Watch® is solely responsible for the conclusions reached in this report. 2 Final Seafood Recommendation Criterion Score (0-10) Rank Critical? C1 Data 6.25 YELLOW C2 Effluent 9.00 GREEN NO C3 Habitat 6.18 YELLOW NO C4 Chemicals 10.00 GREEN NO C5 Feed 10.00 GREEN NO C6 Escapes 4.00 YELLOW NO C7 Disease 8.00 GREEN NO C8 Source 10.00 GREEN 9X Wildlife mortalities 0.00 GREEN NO 10X Introduced species escape 0.00 GREEN Total 63.43 Final score 7.93 OVERALL RANKING Final Score 7.93 Initial rank GREEN Red criteria 0 Interim rank GREEN FINAL RANK Critical Criteria? NO GREEN Scoring note – scores range from zero to ten where zero indicates very poor performance and ten indicates the aquaculture operations have no significant impact. Summary The final numerical score for seaweeds farmed in open water systems worldwide is 7.93, which is in the green range. Three criteria (data, habitat and escapes) received yellow rankings; however, this did not affect the overall green ranking. 3 Executive Summary Around the world, particularly in Asia, seaweed is commercially produced on coastal farms. These farms can vary in size, with very large farms producing millions of metric tons of seaweed per year. -

Daftar Produk Halal

Dunia Daging KELOMPOK DAGING DAN PRODUK DAGING OLAHAN Fronte : Vegetable Chicken Sausage, Fronte : 00010013540900 141213 Food Industries, November - Desember 2012 Beef Frankfurter, Fronte : Chicken Frankfurter, PT Nama Produk Sertifikat Exp Produsen Fronte : Blackpepper Beef Sausage Reguler, Fronte : Breakfast Beef Sausage, Fronte : Beef Frankfurter Kibif Rolade Sapi, Kibif Rolade Sapi (wet mar- Bina Mentari Skinless, Fronte : Chicken Frankfruter Skinless, Fronte : Sosis Ayam (Chicken Chipolata), Fronte : Sosis ket), Kibif Beef Salami, Kibif Daging Sapi Lada ‘00010060390212 010214 Tunggal, PT Sapi (Beef Bockwurst), Fronte : Cheesy Beef Sausage, Fronte : Blackpepper Beef Sausage, Fronte : Hitam, Kibif Sosis Sapi, Kibif Sosis Sapi Chicken Luncheon (wet market), Kibif Beef Pepperoni, Kibif Nugget Sapi, Kibif Bakso Sapi WK, Kibif Bakso Sapi WM, Kibif Dunia Daging Meat Ball Super, Kibif Bakso Halus, Kibif Beef Patties, Kibif Burger Patties Black Pepper, Kibif Beef Burger Fronte : Beef Lucheon, Fronte : Galapeno Beef 00010013540900 141213 Food Industries, Bulgogi, Kibif Burger Daging Sapi Sasage, Fronte : Roast Beef, Fronte : Beef PT Kerupuk Ikan Lele, Fish Cookies (Kerupuk 00100062720912 250914 Mina Sejahtera Coctail, Fronte : Sosis sapi Asap, Fronte : Veal Bratwurst, Fronte : Corn Beef sausage, Fronte : Garlic Beef Ikan Lele) Sausage, Fronte : Paprica Beef Sausage, Fronte : Beef Pastrami, Fronte : Beef Pepperoni, Fronte : Beef MARINADE, MRND CHICKEN STEAK , SPICY Frozen Food Salami WING , MRND SIRLOIN STEAK , SPICY WING ‘00010043750307 110414 -

Menu Item with Substitutions And/Or Omissions of Ingredients

STARTERS WOK FARE Chicken – 15 Beef or Pork – 15 Tofu – 13 Shrimp - 17 Entrees are served with steamed rice. Brown rice $1.5 extra Salt & Pepper Chili Calamari 10 Lightly battered calamari tossed in chopped onions, All Tofu options are with vegetarian sauce. jalapeno peppers, five-spice salt & black pepper. Thai Basil Green Bean Beef (GFA) Salt & Pepper Fried Tofu 7 Beef, green beans & Thai basil Lightly battered tofu tossed in five-spice salt & black pepper. Cashew Chicken (GFA) Vietnamese Egg Rolls (2) 5 Crispy, fried egg rolls made with pork, vegetables & Chicken, cashew nuts, bell peppers, zucchini, mushrooms & Thai basil. bean thread noodles. Served with Vietnamese nuoc mam dipping sauce. Spicy Ginger Shrimp (GFA) With Salad Platter +3 Shrimp, bamboo shoots, bell peppers, julienne carrots, roasted peanuts & scallions in a spicy ginger sauce. Leaf lettuce, cucumber, cilantro, basil & pickled daikon & carrots. Spicy Pineapple Chicken (GFA) Takoyaki (6) 7 Chicken, pineapple, bell peppers, bamboo shoots & onions in a Fried octopus balls with batter served with bonito flakes, spicy garlic sauce. Japanese mayo, aonori (green laver) & takoyaki sauce. Chicken Gyoza (6) 6 Curry Coconut Chicken (GF) Japanese-style dumplings filled with chicken & vegetables. Thai-style red curry with chicken, bell peppers, bamboo shoots & onions in a creamy curry coconut sauce. Spicy Dumplings (6) 7 Steamed chicken dumplings served in spicy chili ENTREES sauce, topped with green onions & ginger. Mongolian Beef (GFA) 17 Sliced flank steak, scallions, garlic & chili peppers. Tempura Platter Japanese-style deep-fried battered prawns & vegetables. Served General Tso's Chicken 15 with tempura dipping sauce Lightly battered chicken in a tangy garlic sauce with steamed Tempura Vegetables 12 broccoli. -

6 Aug 2018 Mugen Menu A3 Officeworks

MUGEN RAMEN MUGEN JAPAS BEERS LIQUER Wafu Tsukemen – Dipping Ramen Small $17 Gyoza $18 Thunder Road Full Steam Pale Lager on Tap $9 Oubai Ume-Shu $13 Large $19 Dashi and Soy Sauce broth, House made thick noodles House Made Pork Gyoza served with Mugen’s Special (7 pcs) (Thunder Road Brewing Company, Brunswick, Victoria) Full served with Slow Cooked Pork (Chashu), Bamboo Shoots Sauce Steam is a pale lager with a clean, pure, crisp malty profile, a Aragoshi Ume-Shu $13 and Seaweed subtle hint of wheatiness, a surprisingly rich texture – 4.6 ABV Potato Salad $17 Curry Tsukemen – Dipping Ramen Small $17 Aragoshi Momo-Shu $13 Japanese Curry flavoured Dashi broth, House made thick Large $19 Japanese Potato Salad with Cherry Wood Smoke served Thunder Road Brewery Pale Ale $9 noodles served with Slow Cooked Pork (Chashu), Bamboo with Toast and Prosciutto A pale ale with excellent balance between the malt and hop Yuzu-Shu $13 Shoots and Seaweed profile that carries spicy citrus and passion fruit aromas - 4.6 Chicken-Nanban $18 Goma Tsukemen – Dipping Ramen Small $17 ABV Deep fried chicken thigh, dipped in sweet & sour sauce WINES Sesame Soy sauce broth, House made thick noodles served Large $19 served with Japanese Tartare sauce and mixed leave with Slow Cooked Pork (Chashu), Bamboo Shoots and Thunder Road Brewery Pacific Ale $9 Sparkling salad Seaweed A relatively new Australian style, this lovely beer highlights NV Holly’s Garden ‘Blanc de Noir’, Whitlands, VIC $11/$50 the Galaxy hop with pineapple, passion fruit and citrus notes – Wafu Ramen -

Food Calories Chart

FOOD CALORIE CHART HOW MANY CALORIES HAVE YOU EATEN? Food Portion Calories Mee Rebus 1 plate 558kcal Mee Siam 1 plate 519kcal Mee Soto 1 bowl 432kcal Mee Goreng 1 plate 660kcal Noodles with Minced Pork & Mushroom (Dry) 1 bowl 511kcal Ban Mian (with egg, meat & vegetables) 1 bowl 475kcal Fried Kway Teow (with cockles) 1 plate 743kcal Hor Fun 1 plate 708kcal Laksa 1 bowl 589kcal Fried Beehoon (plain) 1 plate 252kcal Lor Mee 1 bowl 383kcal Fishball Noodles, Dry 1 bowl 364kcal Fishball Noodles, Soup 1 bowl 330kcal Fish Head Beehoon Soup 1 bowl 666kcal Fish Slice Beehoon Soup 1 bowl 349kcal Fried Hokkien Prawn Mee 1 plate 615kcal Prawn Noodles, Dry 1 bowl 459kcal Prawn Noodles, Soup 1 bowl 293kcal Wanton Noodles, Dry 1 bowl 409kcal Wanton Noodles, Soup 1 bowl 217kcal Kway Chap (with meat, intestine & taupok) 1 bowl 648kcal FOOD CALORIE CHART HOW MANY CALORIES HAVE YOU EATEN? Food Portion Calories Chicken Porridge 1 bowl 214kcal Fish Porridge 1 bowl 261kcal Pork Porridge 1 bowl 362kcal Century Egg Porridge 1 bowl 422kcal Char Siew Rice 1 plate 600kcal Duck Rice 1 plate 706kcal Chicken Rice (with meat) 1 plate 702kcal Fried Rice 1 plate 508kcal Nasi Lemak 1 plate 494kcal Nasi Briyani with Chicken 1 plate 880kcal Fish & Chips 1 serving 848kcal Stingray (with chili sauce; grilled) 1 serving 347kcal Bak Kut Teh 1 bowl 342kcal Herbal Black Chicken Soup 1 bowl 186kcal Tom Yam Seafood Soup 1 bowl 271kcal Pig Organ Soup 1 bowl 158kcal Watercress and Pork Ribs Soup 1 bowl 92kcal Chicken Curry 1 bowl 450kcal Fish Head Curry 1 plate 288kcal FOOD CALORIE -

Chef's Selection of High Tea

1 厨师精选茶点套餐(两人份) chef’s selection of high tea set (2 persons) 335 茶苑招牌牛肉面 signature beef noodle soup 140 招牌鲜虾肉馄饨(含猪肉) shrimp wonton soup (contains pork) 130 沪式鲜肉锅贴 pot-sticker dumpling, minced pork 95 鸡丝开洋葱油拌面 noodle, dried shrimp, shredded chicken, shallot oil, soy sauce 95 茶苑自制小食 tea house home-made snacks 95 东海香辣鱿鱼丝,咖喱牛肉干 szechuan spice dried shredded squid, homemade dried curry beef 苔菜焗腰果,南塘原味油赞子 crispy cashew nut with seaweed, fried dough twists 甬城蟹粉小笼包 steamed crabmeat dumpling 85 杨枝甘露 chilled mango sago cream with pomelo 85 木瓜蜂蜜枸杞炖雪梨 boiled pear, papaya, wolfberry, honey 85 所有价格以人民币计算,已包含服务费及相关政府税费 all prices are in cny and inclusive all service charge and government tax 2 茶苑手工干菜酥饼 baked minced pork and dried preserved vegetable puff 70 红糖麻糍 crispy glutinous rice cake, brown sugar 70 芒果雪媚娘 glutinous rice ball, mango cream 70 农家绿豆酥 mung bean cake 70 茶苑自制苹果干 homemade dried apple 55 时令鲜果盘 seasonal fruit platter 120 所有价格以人民币计算,已包含服务费及相关政府税费 all prices are in cny and inclusive all service charge and government tax 3 精选混合茶 RECOMMENDED TEA 位/PERSON 意柔香 fragrance 115 重瓣红玫瑰,大枣,玉竹, roses, chinese date, radix 茉莉花,桂圆,木瓜 jasmine, dried longan, papaya 醉饮香 charming 菊花,淡竹叶,决明子, chrysanthemum, lophatherum gracile, cassia seed 金银花,枸杞,葛根 honeysuckle, medlar, the root of kudzu vine 窈窕香 sylphlike 重瓣红玫瑰,荷叶,玫瑰茄, roses, lotus leaf, roselle 菊花,牛蒡根,青钱柳叶 chrysanthemum, burdock root, cyclocarya paliurus leaf 和味香 sweet 佛手,茯苓,丹凤牡丹花, fingered citron, poria, peony flowers 山楂,大枣,茶树花 hawthorn, chinese date, tea flower 钱湖香 mild 麦芽,枸杞,山楂,红茶 malt, chinese wolfberry, hawthorn,