Cedar Box Teaching Toolkit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proofed-Stonewall Tribune 050219 Revised.Indd

METICULOUS PROPERTY INSIDE & OUT - 5 bedrms, JUST LISTED - STRIKING BI-LEVEL WITH PIZZAZ BONUS VIDEO + 3 baths, Gorgeous property, pie lot with loads of on a lovely large pie lot Warkinton built a beauty SOCIAL MEDIA family features Balmoral $429,900 Brandt in Warren $324,900 - Matt PROMOTIONPR PACKAGE % FOR MONTH 4 OF MAY WHEN YOU SELL WITH JUST LISTED - ESCAPE THE MADNESS Country loving 10 mins from the city - 2950 sqft, 6.99 acres, Quad Garage’s heated, 30x40 storage bldg $579,900 Brandt Call 204-467-8000 mckillop.ca Stonewall Teulon THURSDAY, VOLUME 10 EDITION 18 MAY 2, 2019 SERVING STONEWALL, BALMORAL, TEULON,Tribune GUNTON, NARCISSE, INWOOD, LAKE FRANCIS, WOODLANDS, MARQUETTE, WARREN, ARGYLE, GROSSE ISLE, ROSSER, STONY MOUNTAIN, ST. LAURENT & KOMARNO Stihl MSA120 C-BQ Chainsaw Battery Operated$ 95 36 V Battery 399 Diggin’ Earth Day BG50 Gas Blower $18900 Stihl MS170 Chainsaw 30 c.c. 16” bar $ 00 1 year warranty 199 Stihl MS291 Chainsaw 56 c.c. $ 95 16” bar 499 1 year warranty TRIBUNE PHOTO BY JO-ANNE PROCTER SHACHTAY East Interlake Conservation District’s manager Armand Belanger introduces Bobby Bend Grade 2 students Mason M., SALES & SERVICE Kaleb P. and Kalli M. to the world of Vermicomposting to celebrate Earth Day on April 23. Vermicomposting uses red Arborg, MB wriggler worms to convert food waste and organic material into a nutrient-rich natural fertilizer that can be used to 204-376-5233 plant Joe Pye Weed seeds. See more photos on page 3. news > sports > opinion > community > people > entertainment > events > classifi eds > careers > everything you need to know OPEN HOUSE – SATURDAY, MAY 4TH 1 P.M. -

Nutrients and Bioactive Potentials of Edible Green and Red Seaweed in Korea K

Sanjeewa et al. Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences (2018) 21:19 https://doi.org/10.1186/s41240-018-0095-y REVIEW Open Access Nutrients and bioactive potentials of edible green and red seaweed in Korea K. K. Asanka Sanjeewa, WonWoo Lee and You-Jin Jeon* Abstract Background: Traditionally, East-Asians (Korea, Japan, and China) utilize seaweeds as a food source and ingredient in traditional medicine. Korea is one of the biggest seaweed producer and consumer in the global trade. Especially, side dishes made from seaweeds are very popular in the traditional Korean cuisines. Seaweeds are popular as fresh vegetable salads and soup or eaten as snacks. Main body: Seaweeds are rich in essential nutrients, minerals, and vitamins as well as a promising source of novel bioactive compounds. The compounds (polysaccharides, polyphenols, and sterols) present in the edible Korean seaweeds possess important bioactive properties such as antioxidant, anti-inflammation, anticancer, anti-diabetic, and anticoagulant properties. Thus, the long-term consumption of seaweed has a potential to reduce the risk of cancer, diabetes, obesity, and inflammation-related complications. However, seaweed consumption is limited to the small population around the globe. Thus, it is important to increase the awareness of the health benefits of seaweeds consumption among the general population. Short conclusion: In the present study, we discussed some popular green and red edible Korean seaweeds and their health-promoting properties. This study might be useful to increase the public awareness of the consumption of seaweed as a food source. Keywords: Edible seaweed, Bioactive, Functional foods Background public awareness, demand for seaweeds and their commer- Seaweeds have been used as human food since ancient times. -

OMM Play Guide R2

PLAY GUIDE 2015 2016 About ATC …………………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Introduction to the Play ……………………………………………………………………..….. 2 Meet the Author …………………………………………………..…………………………… 2 Meet the Characters …………………………………………….……………….…………….. 4 Adaptation: Of Mice and Men …………………………………..….……………………………. 5 Themes in the Play ……………………………………………..……………………………… 7 Cultural Context: 1930s America ……………………..…………………………………………. 8 The Wild West …………………………………………………………………………………. 13 Social Perceptions of Disability …………………………………………………………………. 16 Behind the Scenes: Meet Lola ………………………………………………………………….. 18 Game Rules …………………………………………………..………………………………. 19 Glossary ……………………………………………………………………………………… 21 Of Mice and Men Play Guide edited and designed by Katherine Monberg, ATC Literary Manager, with assistance from Luke Young, Learning & Education Manager; Shelby Athouguia and Bryanna Patrick, Learning & Education Associates; Kacie Claudel, Chloe Loos, Gabriel Oladipo, and Angelina Valencia, Contributing Writers; and Joy Nielsen, Editorial Assistant. SUPPORT FOR ATC’S LEARNING & EDUCATION PROGRAMMING HAS BEEN PROVIDED BY: APS Rosemont Copper Arizona Commission on the Arts Stonewall Foundation Bank of America Foundation Target Blue Cross Blue Shield of Arizona The Boeing Company City of Glendale The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Community Foundation for Southern Arizona The Johnson Family Foundation, Inc. Cox Charities The Lovell Foundation Downtown Tucson Partnership The Marshall Foundation Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Maurice and Meta Gross Foundation Ford Motor Company -

Super Solitaire™

Nintendo Gateway - Super NES Executive Game Summary Game Title Super Solitaire™ Trademark Super Solitaire™ & © 1993 Extreme Entertainment Group, Inc. Attribution Game This game brings you 12 classic solitaire games in one. Each game features a complete set of Description rules as well as hints for game play. If you think you're good, try the championship and tournament modes. Game play is available in English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish. This is a one-player game. Available games include: Klondike, Cruel, Dozen't Matter, Poker, Free Cell, Pyramid, Aces Up, Canfield, Golf, Stonewall, Florentine, and Scorpion. Controller Control Pad: Move cursor. Information A Button: Bring up menus. B Button: Pick up a card; enter a letter on a password screen. Y Button: Put down a card; close a menu; backspace on the password screen. X Button: Return cursor to stock pile; return to the title screen from the password screen. Start and pause the game. START: Not used. SELECT: "Yes" on the message screens; undo a move. L Button: "No" on the message screens; undo a move. R Button: Strongly Starting a Game: Suggested Put the cursor on the game; it's name will appear. Press the B Button to highlight it. Position cursor over the "OK" and press the B Button. To return to the title screen, press the B Button Info Block while on the "EXIT" icon. Super Solitaire 10/05/2001 Game Redeal: Start new game with new cards. Start over: Start a game over. Undo: Take back the last move. Quit: Return to title screen. Code: Provide the current password. -

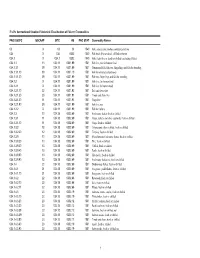

FIC-Prop-65-Notice-Reporter.Pdf

FIC Proposition 65 Food Notice Reporter (Current as of 9/25/2021) A B C D E F G H Date Attorney Alleged Notice General Manufacturer Product of Amended/ Additional Chemical(s) 60 day Notice Link was Case /Company Concern Withdrawn Notice Detected 1 Filed Number Sprouts VeggIe RotInI; Sprouts FruIt & GraIn https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl Sprouts Farmers Cereal Bars; Sprouts 9/24/21 2021-02369 Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Market, Inc. SpInach FettucIne; 02369.pdf Sprouts StraIght Cut 2 Sweet Potato FrIes Sprouts Pasta & VeggIe https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl Sprouts Farmers 9/24/21 2021-02370 Sauce; Sprouts VeggIe Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Market, Inc. 3 Power Bowl 02370.pdf Dawn Anderson, LLC; https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02371 Sprouts Farmers OhI Wholesome Bars Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 4 Market, Inc. 02371.pdf Brad's Raw ChIps, LLC; https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02372 Sprouts Farmers Brad's Raw ChIps Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 5 Market, Inc. 02372.pdf Plant Snacks, LLC; Plant Snacks Vegan https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02373 Sprouts Farmers Cheddar Cassava Root Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 6 Market, Inc. ChIps 02373.pdf Nature's Earthly https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl ChoIce; Global JuIces Nature's Earthly ChoIce 9/24/21 2021-02374 Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- and FruIts, LLC; Great Day Beet Powder 02374.pdf 7 Walmart, Inc. Freeland Foods, LLC; Go Raw OrganIc https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02375 Ralphs Grocery Sprouted Sea Salt Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 8 Company Sunflower Seeds 02375.pdf The CarrIngton Tea https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl CarrIngton Farms Beet 9/24/21 2021-02376 Company, LLC; Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Root Powder 9 Walmart, Inc. -

Stonewall Jackson

AMERICAN CRISIS BIOGRAPHIES STONEWALL JACKSON HENRY ALEXANDER WHITE. A.M.. Ph.D. Author of " Robert E. Lee and the Southern Confederacy," "A History of the United States," etc. PHILADELPHIA GEORGE W. JACOBS & COMPANY PUBLISHERS COPYRIGHT, 1908, BY GEORGE W. JACOBS & COMPANY Published January, 1909 This volume is dedicated to My Wife Fanny Beverley Wellford White PREFACE THE present biography of Stonewall Jackson is based upon an examination of original sources, as far as these are available. The accounts of Jack son s early life and of the development of his per sonal character are drawn, for the most part, from Doctor Eobert L. Dabney s biography and from Jackson s Life and Letters, by Mrs. Jackson. The Official Eecords of the war, of course, constitute the main source of the account here given of Jackson s military operations. Colonel G. F. E. Henderson s Life is an admirable of his career study military ; Doctor Dabney s biography, however, must remain the chief source of our knowledge concerning the personality of the Confederate leader. Written accounts by eye-witnesses, and oral statements made to the writer by participants in Jackson s campaigns, have been of great service in the preparation of this volume. Some of these are mentioned in the partial list of sources given in the bibliography. HENRY ALEXANDER WHITE. Columbia, S. C. CONTENTS CHRONOLOGY 11 I. EARLY YEARS 15 II. AT WEST POINT .... 25 III. THE MEXICAN WAR ... 34 IV. THE VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE 47 V. THE BEGINNING OF WAR . 63 VI. COMMANDER OF VOLUNTEERS AT HARPER S FERRY .. -

FAO's International Standard Statistical Classification of Fishery Commodities

FAO's International Standard Statistical Classification of Fishery Commodities FAO ISSCFC ISSCAAP SITC HS FAO STAT Commodity Names 03 X 03 03 1540 Fish, crustaceans, molluscs and preparations 034 X 034 0302 1540 Fish fresh (live or dead), chilled or frozen 034.1 X 034.1 0302 1540 Fish, fresh (live or dead) or chilled (excluding fillets) 034.1.1 13 034.11 0301.99 1501 Fish live, not for human food 034.1.1.1 39 034.11 0301.99 1501 Ornamental fish, fish ova, fingerlings and fish for breeding 034.1.1.1.10 39 034.11 0301.10 1501 Fish for ornamental purposes 034.1.1.1.20 39 034.11 0301.99 1501 Fish ova, fingerlings and fish for breeding 034.1.2 X 034.110301.99 1501 Fish live, for human food 034.1.2.1 X 034.110301.99 1501 Fish live for human food 034.1.2.1.10 22 034.11 0301.92 1501 Eels and elvers live 034.1.2.1.20 23 034.11 0301.91 1501 Trouts and chars live 034.1.2.1.30 11 034.11 0301.93 1501 Carps live 034.1.2.1.90 39 034.11 0301.99 1501 Fish live, nei 034.1.2.2 X 034.110301.99 1501 Fish for culture 034.1.3 10 034.18 0302.69 1501 Freshwater fishes, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.1 11 034.18 0302.69 1501 Carps, barbels and other cyprinids, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.1.10 11 034.18 0302.69 1501 Carps, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.2 12 034.18 0302.69 1501 Tilapias and other cichlids, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.2.20 12 034.18 0302.69 1501 Tilapias, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.9 10 034.18 0302.69 1501 Miscellaneous freshwater fishes, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.9.20 13 034.18 0302.69 1501 Pike, fresh or chilled 034.1.3.9.30 13 034.18 0302.69 1501 Catfish, fresh or -

Desert Fox Games

DESERT FOX GAMES Many titles now available on the Decision Games online shop in the Desert Fox tab. Some games are one of a kind, list of alternate games is appreciated. MFG Title Price MFG Title Price MFG Title Price Iss # Title Price CSL 1812 40 LWG Ball's Bluff (ziplock) 20 Isandlwana 56 37 Mukden & Moscow Option P25 CSL 1864 40 LWG Battle of the Little Bighorn 68 WDG Vietnam Solitaire 50 38 Great War in Near East 35 CSL 1870 40 LWG Demyansk Shield 62 WDG We Shall Fight: Marne 52 40 Buena Vista & Moscow Burning 35 CSL 1916 40 LWG Dien Bien Phu 64 WDG World War Zed- USA (solitaire) 47 42 Hell B4 Night/Blitz 40 35 CSL 1950 40 LWG Hell Over Korea 40 43 Chattanooga 35 CSL Army Group North 40 LWG Ici, c'est la France! (2nd Ed) 60 MAGAZINES 44 Dark Victory & 2nd Front 35 CSL Army Group South 40 LWG Maori Wars 62 Fire & Movement GMT Ancient Civilizations of LWG Nemesis: Burma 1944 64 1 40 Command Game Only-No mag the Inner Sea 85 LWG Picket Duty 2 70 2-10, 21 25 39 World War 1862 15 GMT Andean Abyss 75 LWG Quatre Batailles en Espagne 98 12-20, 37, 38, 41, 45, 48, 53, 83, 44 Dark Victory & 2nd Front 25 GMT Arquebus 65 LWG Saipan & Tinian 66 137-139, 143, 145, 149, 150 15 50 Back to Iraq (2nd) 15 GMT Battles of Warrior LWG Slouch Hats & Eggshells 48 22-27, 29, 31, 32, 36, 39-40, 42-44, 51 Meuse-Argonne 15 Queen (ziplock) 20 LWG Tanga 1914 64 46-47, 49-52, 54-56, 59, 73,77 10 Warmaster Chess vol 1-3 (one set) 25 GMT Cataclysm 79 LWG Target For Today 80 33-35, 60-67, 68-76, 78-79, 80-93, GMT Colonial Twilight 75 LWG Tonkin 60 95-108, 110, 111, -

Sub-Group Ii—Thematic Arrangement

U.S. SHEET MUSIC COLLECTION SUB-GROUP II—THEMATIC ARRANGEMENT Consists of vocal and instrumental sheet music organized by designated special subjects. The materials have been organized variously within each series: in certain series, the music is arranged according to the related individual, corporate group, or topic (e.g., Personal Names, Corporate, and Places). The series of local imprints has been arranged alphabetically by composer surname. A full list of designated subjects follows: ______________________________________________________________________________ Patriotic Leading national songs . BOX 458 Other patriotic music, 1826-1899 . BOX 459 Other patriotic music, 1900– . BOX 460 National Government Presidents . BOX 461 Other national figures . BOX 462 Revolutionary War; War of 1812 . BOX 463 Mexican War . BOX 464 Civil War . BOXES 465-468 Spanish-American War . BOX 469 World War I . BOXES 470-473 World War II . BOXES 474-475 Personal Names . BOXES 476-482 Corporate Colleges and universities; College fraternities and sororities . BOX 483 Commercial entities . BOX 484 1 Firemen; Fraternal orders; Women’s groups; Militia groups . BOX 485 Musical groups; Other clubs . BOX 486 Places . BOXES 487-493 Events . BOX 494 Local Imprints Buffalo and Western New York imprints . BOXES 495-497 Other New York state and Pennsylvania imprints . BOX 498 Rochester imprints . BOXES 499-511 ______________________________________________________________________________ 2 U.S. Sheet Music Collection Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections, Sibley Music Library Sub-Group II PATRIOTIC SERIES Leading National Songs Box 458 Ascher, Gustave, arr. America: My Country Tis of Thee. For voice and piano. In National Songs. New York: S. T. Gordon, 1861. Carey, Henry, arr. America: The United States National Anthem. -

SW Monthly Onlinecover

Werk Thoroughbred Consultants, Inc. presents WTC’s STAKES & MAIDEN WINNERS MONTHLY October, 2009 Featuring a monthly recap of the winners of unrestricted stakes races in North America and Europe, which includes our WTC “Best of Sale” selections and Mating Recommendations. Also included is a list of all maiden winners for the month sorted by sire. Published by Werk Thoroughbred Consultants, Inc. PO Box 1926, Fremont, CA 94538-0192 (510) 490-1111 / (510) 490-4499 (fax) www.werkhorse.com email: [email protected] Copyright 2009 WERK THOROUGHBRED CONSULTANTS MATINGS and BEST OF SALE STAKES WINNERS (Domestic Stakes $25,000 and up · October 1 through October 31, 2009) NORTH AMERICAN GRADED STAKES RESULTS Grade 1 Races SHADWELL TURF MILE S. ( GI ), KEE, $600,000, 3YO/UP, 1MT, 10-10. — COURT VISION, c, 4, Gulch--Weekend Storm, by Storm Bird. WTC “BEST OF SALE” – KEESEP06 - $180,000 – 2.0 STARS – A NICK ($350,000 2yo 2007 FTFFEB.). O-IEAH Stables and Resolute Group Stables, B-W. S. Farish &Kilroy Thoroughbred Partnership (KY), $360,000. — Karelian, g, 7, Bertrando--Leaning Tower, by Theatrical (IRE). WTC “BEST OF SALE” – KEESEP03 – ($47,000)RNA – 1.5 STARS – C+ NICK O-Green Lantern Stables LLC, B-Green Lantern Stables (KY), $120,000. — Mr. Sidney, h, 5, Storm Cat--Tomisue's Delight, by A.P. Indy. WTC “BEST OF SALE” – KEESEP05 - $3,900,000 – 3.5 STARS – A NICK O-Circle E Racing, B-Hilbert Thoroughbreds (KY), $60,000. JOE HIRSCH TURF CLASSIC INVITATIONAL S. ( GI ), BEL, $600,000, 3YO/UP, 1 1/2MT, 10-3. —INTERPATATION, g, 7, Langfuhr--Idealistic Cause, by Habitony. -

Seafood Watch

Farmed Seaweed Image © Monterey Bay Aquarium Worldwide All Production Systems July 28, 2014 Andrea Flynn, Consulting Researcher Disclaimer Seafood Watch® strives to have all Seafood Reports reviewed for accuracy and completeness by external scientists with expertise in ecology, fisheries science and aquaculture. Scientific review, however, does not constitute an endorsement of the Seafood Watch® program or its recommendations on the part of the reviewing scientists. Seafood Watch® is solely responsible for the conclusions reached in this report. 2 Final Seafood Recommendation Criterion Score (0-10) Rank Critical? C1 Data 6.25 YELLOW C2 Effluent 9.00 GREEN NO C3 Habitat 6.18 YELLOW NO C4 Chemicals 10.00 GREEN NO C5 Feed 10.00 GREEN NO C6 Escapes 4.00 YELLOW NO C7 Disease 8.00 GREEN NO C8 Source 10.00 GREEN 9X Wildlife mortalities 0.00 GREEN NO 10X Introduced species escape 0.00 GREEN Total 63.43 Final score 7.93 OVERALL RANKING Final Score 7.93 Initial rank GREEN Red criteria 0 Interim rank GREEN FINAL RANK Critical Criteria? NO GREEN Scoring note – scores range from zero to ten where zero indicates very poor performance and ten indicates the aquaculture operations have no significant impact. Summary The final numerical score for seaweeds farmed in open water systems worldwide is 7.93, which is in the green range. Three criteria (data, habitat and escapes) received yellow rankings; however, this did not affect the overall green ranking. 3 Executive Summary Around the world, particularly in Asia, seaweed is commercially produced on coastal farms. These farms can vary in size, with very large farms producing millions of metric tons of seaweed per year. -

Directory Floor 1 | Merchandise Mart

DIRECTORY FLOOR 1 | MERCHANDISE MART The World’s Largest Collection of Premier Boutiques for Home Building and Renovation 45 BOUTIQUES. 1 LOCATION | LUXEHOME.COM CUSTOM SHADES BLINDS & DRAPERY VISIT US IN SUITE 105 Visit us at our other location: Oakbrook Center: 89 Oakbrook Center theshadestore.com/trade | [email protected] | 866.505.5827 Inspired design for the luxurious lifestyle. The Wood-Mode Lifestyle Design Center is an inspirational resource for homeowners, architects, interior designers and Lifestyle Design Center trade professionals. Visit the showroom to view the latest products and lifestyle design themes from Wood-Mode, and experience unparalleled access to all of the qualities that make our brand the leader in custom cabinetry in the U.S. and Canada. To discover your inspiration, visit Suite 119 or chicago.wood-mode.com. ©2019 Wood-Mode, Inc. Thoughtful design. Timeless style. From flush installation and premium materials, to perfectly balanced proportions, a Bosch kitchen is designed to consider every last detail, including you. Experience & Design Center 222 W Merchandise Mart Plaza, Suite 108 Chicago, IL 60654 To make an appointment, call 312.832.3200 www.bosch-home.com/us | © 2018 BSH Home Appliances Corporation. WELCOME TO LUXEHOME POGGENPOHL INSIDE THE CONTACT US LUXEHOME MANAGEMENT DIRECTORY Myron Maurer Merchandise Mart Chief Operating Officer 222 Merchandise Mart INFORMATION 5 312-527-7515 Plaza, Suite 470 [email protected] Chicago, IL 60654 312-527-4141 Welcome to LuxeHome 5 themart.com Susan McCullough Hours and Contact Information 5 Senior Vice President Published by theMART, 312-527-7756 a Vornado property, [email protected] the Directory is the LUXEHOME FLOOR PLAN 10 exclusive and official Toni McIntosh directory of LuxeHome.