The State of Play on International Piracy and Anti-Counterfeiting Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Climategate” (PDF)

The Emails from the University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit On or about November 19, 2009, as yet unknown persons hacked into an email server at the University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit (CRU) in Norwich, U.K. The CRU is an academic department specializing in climate research and is particularly known for reconstructing past global surface temperatures on the decade to millennium time scales. The CRU is one of three organizations worldwide that have independently compiled thermometer measurements of local temperatures from around the world to reconstruct the history of average global surface temperature for the past 130 ‐ 150 years. The other two groups are in the United States (NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center and the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies). From a much larger number of emails, the hackers selected and posted more than 1000 on a publicly accessible file server in Russia. The vast majority of the 1000+ emails are routine and unsuspicious. Perhaps one or two dozen of the email exchanges give the appearance of controversy, though no unethical behavior has yet been documented. Professor Phil Jones, director of the CRU, was involved in most of these email exchanges. He has temporarily stepped down as the CRU director pending the outcome of an independent investigation instigated by the university. Although a small percentage of the emails are impolite and some express animosity toward opponents, when placed into proper context they do not appear to reveal fraud or other scientific misconduct by Dr. Jones or his correspondents. The most common accusations of misconduct center around two general themes: 1. -

North Minneapolis—A Welcoming Home for Business Welcome

GrowNorth! North Minneapolis—A welcoming home for business Welcome If you have any questions or ideas, please contact your personal business development consultant at the City of Minneapolis, Casey Dzieweczynski 612-673-5070 On behalf of the City of Minneapolis, we would like to thank you for considering North Minneapolis as the new location for your business. Today is a great time to invest, and here’s why: • North Minneapolis is conveniently located near downtown, accessible from the entire metro and has great freeway access to Interstates 94 and 394. The area is also served by Olson Highway and Highway 100 with a connection to South Minneapolis via the Van White Memorial Boulevard. • The City’s economic development team can help find the right location for your busi- ness through its site assistance support. Available real estate includes significant areas of industrially zoned land, well-served by freeways and freight rail. • The City offers several business financing programs, ranging from $1,000 to $10 million and development grants to assist business owners in acquiring property, purchasing equipment and making building improvements. • The City’s employment and training program team can assist with workforce recruit- ment and training programs so your staff is knowledgeable and productive the minute they are hired. • The Minneapolis-coordinated development review will help you successfully navigate the regulatory process, which includes Planning/Zoning, Building Plan Review, Permit- ting and Licensing, and other regulatory review agencies. No one knows Minneapolis the way we do. The Department of Community Planning and Economic Development is ready to support you with all your business needs—from finance to site location, to customized training to fit your employment needs—and is here to help you every step of the way. -

Global Warming from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia This Article Is About the Current Change in Earth's Climate

Global warming From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the current change in Earth's climate. For general discuss ion of how the climate can change, see Climate change. For other uses, see Globa l warming (disambiguation). Page semi-protectedThis is a featured article. Click here for more information. refer to caption Global mean land-ocean temperature change from 1880?2012, relative to the 1951?1 980 mean. The black line is the annual mean and the red line is the 5-year runni ng mean. The green bars show uncertainty estimates. Source: NASA GISS. (click fo r larger image) Map of temperature changes across the world key to above map of temperature changes The map shows the 10-year average (2000?2009) global mean temperature anomaly re lative to the 1951?1980 mean. The largest temperature increases are in the Arcti c and the Antarctic Peninsula. Source: NASA Earth Observatory[1] refer to caption Fossil fuel related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions compared to five of the IPCC' s "SRES" emissions scenarios. The dips are related to global recessions. Image s ource: Skeptical Science. Global warming refers to an unequivocal and continuing rise in the average tempe rature of Earth's climate system.[2] Since 1971, 90% of the warming has occurred in the oceans.[3] Despite the oceans' dominant role in energy storage, the term "global warming" is also used to refer to increases in average temperature of t he air and sea at Earth's surface.[4][5] Since the early 20th century, the globa l air and sea surface temperature has increased about 0.8 C (1.4 F), with about two- thirds of the increase occurring since 1980.[6] Each of the last three decades h as been successively warmer at the Earthfs surface than any preceding decade sinc e 1850.[7] Scientific understanding of the cause of global warming has been increasing. -

The Development of CCS Pipeline Network : Two Stage Optimization

Pertamina Energy Outlook 2015 [email protected] Darmawan Prasodjo, PhD Chairman of the Board, Petronomist.com President Commissioner, Ametis Energi Nusantara Ekonom Energi, DPP PDI-Perjuangan 1 BB 7562BC1C 2 The Number of Motor Vehicles 90 80 Sepeda Motor 70 Truk 60 Bis Mobil Penumpang 50 Juta 40 30 20 10 0 3 Who are we? (in term of oil and gas power) 4 Outline Climate Change and Its Policy Implications Biofuel as a Solution Masalah Tata Kelola Conclusion 5 Surface Temperature Increase 6 Sources of Greenhouse Gases 7 Emission and Emission Per Capita 8 Emission and Emission Per Capita 20 18 7 Annual Emission Emission Per Capita 16 6 14 /year) 5 12 4 10 gigatons ( 3 8 6 2 4 Emission Emission 1 2 0 0 capita) per (tons capita per Emission 8 Renewable Energy 9 The Challenge of Renewable Energy: Cost Cost and Emission of 14 Different Energy Sources 1200 12 Cost 1000 10 Emission 800 8 600 6 400 4 g/KWH Emission Cost Cents/KWH Cost 2 200 0 0 10 Coal Consumption in the US and China 11 Renewable Energy In China 12 Environmental Treaties Kyoto Protocol – 1997 Washington Declaration – 2007 33rd G8 Summit, Germany – 2007 Vienna Climate Change Talks, Vienna – 2007 UN Climate Change Conference, Bali– 2007 UN Climate Change Conference, Poland – 2008 UN Secretary General Summit on CC – 2009 UN Climate Change Conference, Copenhagen - 2009 UN Climate Change Conference, Cancun - 2010 Durban, South Africa – 2011 UN Climate Change Conference, Warsaw 2013 13 Indonesian Policy Implication? What kind of Climate Answer: Serving its Change Policy Indonesia -

2014 Showguide

CANADA’S MEETINGS + EVENTS SHOW SHOW GUIDE 2014 It’s time to PUSH YOUR BOUNDARIES + 2 DAYS + 16 SESSIONS + 700+ EXHIBITORS + 1,000s OF IDEAS A world of opportunities 2014Showguide_pgs 01-33. 63, 64REV.indd 1 14-07-24 10:09 AM “ , the best meetings .” We know organizing meetings is diffi cult. That’s why we’ve created solutions to make it easier: Personal Preference Menus. Healthy off erings made to order. Even for large groups. Group Bill. One consolidated, customizable e-bill to make your process seamless. Passkey. A digital dashboard that keeps tabs on group reservations and check-ins in real time. More Locations. Hyatt is expanding its presence in key destinations worldwide, including Atlanta, Chicago, Miami, New York, Tysons Corner, Baha Mar, Shanghai, Moscow, Tokyo and Rio de Janeiro. Call .. and or visit hyattmeetings.com to learn more. Forward-Looking Statements in this document, which are not historical facts, are forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Our actual results, performance or achievements may differ materially from those expressed or implied by these forward-looking statements. In some cases, you can identify forward-looking statements by the use of words such as “may,” “could,” “expect,” “intend,” “plan,” “seek,” “anticipate,” “believe,” “estimate,” “predict,” “potential,” “continue,” “likely,” “will,” “would” and variations of these terms and similar expressions, or the negative of these terms or similar expressions. Such forward-looking statements -

Univ Alaska Energy Study II 9 30 08.Indd

Energy and the Environment at the University of Alaska Anchorage October 2008 Hammel, Green and Abrahamson, Inc. 701 Washington Avenue North Minneapolis, MN 55401 Doug Maust, PE p. 612 - 382 - 5650 f. 612 - 758 - 9463 [email protected] Preparing this report is dependent upon people who have taken time out of their busy schedules to learn about carbon management and gather data that is often obscured in other reports and files. A special thanks goes to Connie Jolin and Wayne Morrison who dug through files to gather utility and fuel purchase data. Larry Foster and Margaret King provided review of the documents and thoughtful comments regarding our approach to the work. The Institute of Social and Economic Research ISER’s Nick Szymoniak and Stephen Colt took on the particularly interesting challenge of estimating the carbon foot print associated with commuting and vehicles used by faculty, staff and students. In response to the leadership of Fran Ulmer the Chancellor of the University of Alaska Anchorage, Michael Smith and Christopher Turlettes anticipated the University’s need for these metrics and commissioned this report. Table of Contents Executive Summary Introduction Climate Change Background Carbon Dioxide Equivalency CAMPUS CARBON DIOXIDE EQUIVALENT EMISSIONS Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions DIRECT GHG EMISSIONS INDIRECT GHG EMISSIONS OTHER INDIRECT GHG EMISSIONS Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Initiatives VOLUNTARY REDUCTION INITIATIVES – THE CLIMATE REGISTRY OTHER VOLUNTARY REDUCTION INITIATIVES Advantages of Managing Greenhouse Gas -

Global Marketing Management, 5Th Edition

rrrrrrrrrrrrrrr GLOBAL MARKETING MANAGEMENT rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr 5TH EDITION This page intentionally left blank rrrrrrrrrrrrrrr GLOBAL MARKETING MANAGEMENT rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr 5TH EDITION Masaaki Kotabe Temple University Kristiaan Helsen Hong Kong University of Science and Technology JOHN WILEY &SONS, INC. DEDICATION To my sons and SDK —M.K. To my mother and A.V. —K.H. Vice President & Executive Publisher George Hoffman Executive Editor Lise Johnson Senior Editor Franny Kelly Production Manager Dorothy Sinclair Senior Production Editor Valerie A. Vargas Marketing Manager Diane Mars Creative Director Harry Nolan Senior Designer James O’Shea Production Management Services Elm Street Publishing Services Senior Illustration Editor Anna Melhorn Photo Associate Sheena Goldstein Assistant Editor Maria Guarascio Editorial Assistant Emily McGee Associate Media Editor Elena Santa Maria Cover Photo Credit ª Daniel lvascu/iStockphoto This book was set in 10/12pt Times Ten Roman by Thomson Digital and printed and bound by Courier- Kendallville. The cover was printed by Courier-Kendallville. Copyright ª 2010, 2008, 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, website www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, (201)748-6011, fax (201)748-6008, website http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. -

Discussing Global Warming in the Security Council: Premature and a Distraction from More Pressing Crises Brett D

22 WebMemo Published by The Heritage Foundation No. 1425 April 16, 2007 Discussing Global Warming in the Security Council: Premature and a Distraction from More Pressing Crises Brett D. Schaefer and Ben Lieberman On April 17, the United Nations Security Coun- ing the consequences of global warming. The focus cil will discuss the security implications of global of these efforts and discussions is to clarify the sci- warming for the first time. The issue was placed on ence of global warming and weigh the costs of the agenda by the United Kingdom, which assumed action to address global warming against the the rotating presidency of the Council for April. risks of inaction. A debate in the Security Council is According to Foreign Secretary Margaret Beckett: unlikely to contribute to these ongoing efforts. The destruction described in [the recently Finally, the Security Council has a full docket of released summary of the Fourth Assessment immediate threats to international peace and secu- Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on rity that is has failed to resolve. Focusing on specu- Climate Change] is a threat not only to the lative threats that may arise decades in the future UK’s prosperity but also to international undermines the seriousness of the body and is an peace and security. That is why, at the UK’s affront to those suffering from immediate crises. initiative, the UN Security Council will on Worse, it distracts the Council from pressing threats the 17th April hold its first ever discussion to international peace and security. on the security implications of climate The Uncertainty Surrounding Catastrophic change. -

COLLECTION AGENCIES LICENSE INFORMATION This Information

COLLECTION AGENCIES LICENSE INFORMATION AS OF 3/13/2020 This information allows you to verify whether a collection agency is licensed by the State of Colorado. You may also determine whether there is any public record of action involving this office and the collection agency. The address listed is for the principal place of business. Contact our office for information on other branch office locations. Collection Agency Licenses A collection agency license is required, in most cases, to collect debts in default owed to others or that were originally owed to others. Only one license is required regardless of the number of branch offices. Generally, creditors collecting debts they originated or purchased before the debts were in default do not need a license. Collection agency licenses expire July 1st of each year and must be renewed at that time. “Status” Category The “Status” category provides the following information: A = license is active C= license is been cancelled (often due to a change in ownership whereby the new owners must apply for a new license and former owners’ license is “cancelled”) D = license was denied E = license his expired (often due to failure to renew license on time or failure to maintain a surety bond) R = license was been revoked “Action” Category In addition to the “Status” column that shows revocations, the “Action” category enables you to determine whether the licensee was subject to legal or administrative action by this office or the licensee entered into a voluntary settlement with this office. If the entry is “yes,” the licensee may have been subject to one or more letters of admonition, suspension of the license, a judgment or order against the licensee, or other action, including payments (fines, penalties, consumer refunds, or other monetary payments). -

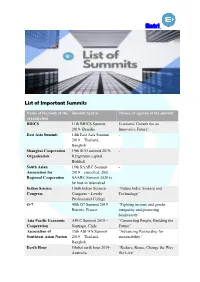

Entri List of Important Summits

Entri List of Important Summits Name of the body of the Summit held at Theme or agenda of the summit organization BRICS 11th BRICS Summit Economic Growth for an 2019- Brasilia Innovative Future’. East Asia Summit 14th East Asia Summit - 2019 – Thailand, Bangkok Shanghai Cooperation 19th SCO summit 2019- - Organisation Kyrgyzstan capital, Bishkek South Asian 19th SAARC Summit - Association for 2019 – cancelled. 20th Regional Cooperation SAARC Summit 2020 to be host in Islamabad Indian Science 106th Indian Science “Future India: Science and Congress Congress – Lovely Technology” Professional College G-7 45th G7 Summit 2019 – “Fighting income and gender Biarritz, France inequality and protecting biodiversity” Asia Pacific Economic APEC Summit 2019 – “Connecting People, Building the Cooperation Santiago, Chile Future” Association of 35th ASEAN Summit “Advancing Partnership for Southeast Asian Nation 2019 – Thailand, sustainability.” Bangkok. Earth Hour Global earth hour 2019- “Reduce, Reuse, Change the Way Australia We Live” Entri BIMSTEC 5th BIMSTEC Summit - 2019 – Sri Lanka (to be held) Indo-Africa Summit 4th Indo-Africa Forum “India and Africa: Deepening the Summit 2018 – New Security Engagement” Delhi. This Summit is held every 3 years CHOGM Summit CHOGM 2019 Meeting – Delivering A Common Future: Rwanda Connecting, Innovating, Transforming’ COP (UNFCCC) COP 25th 2019- Madrid, - Spain (to be held in December) HEMCE- High Energy 12th High Energy - Materials Society of Materials Conference India 2019 – IIT Madras, Chennai, India. 3rd Asian Ministerial New Delhi Tiger conservation Conference on Tiger Conservation World Government 7th World Government ‘Shaping Future Governments,’ Summit Summit- Dubai G-20 14th G 20 Summit 2019 – 8 themes of G 20 Summit – Osaka, Japan “Global Economy”, “Trade and Investment”, “Innovation”, “Environment and Energy”, “Employment”, “Women’s empowerment”, “Development” and “Health”. -

Discussion Paper Series No 18

Understanding Macro and Asset Price Dynamics During the Climate Transition Discussion Paper Series No. 18 / 2019 ISSN 2345-0835 (online) Discussion Paper Series No. 18 / 2019 Michael Donadelli (University of Brescia, Research Center SAFE)12 Patrick Grüning (Bank of Lithuania, Vilnius University)23 Steffen Hitzemann (Rutgers Business School)34 December 201945 1 Department of Economics and Management, University of Brescia and Research Center SAFE, Goethe University Frankfurt. Mailing address: Via S. Faustino 74/b, 25122, Brescia, Italy. E-mail: [email protected]. 2 Center for Excellence in Finance and Economic Research (CEFER), Bank of Lithuania, and Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Vilnius University. Mailing address: Totorių g. 4, 01121 Vilnius, Lithuania. E-mail: [email protected]. 3 Department of Finance and Economics, Rutgers Business School. Mailing address: 100 Rockafeller Road, Piscataway, NJ 08854, United States. E-mail: [email protected]. 4 We would like to thank Matthias Kruttli, Delphine Lautier, Luca Taschini, Nicolas Treich, Gauthier Vermandel, as well as participants of the 2019 Toulouse Conference on the Economics of Energy and Climate, the 2019 Commodity and Energy Markets Association Annual Meeting at Carnegie Mellon, and of several other events for their helpful comments and suggestions. We gratefully acknowledge research and financial support from the Research Center SAFE, funded by the State of Hessen initiative for research LOEWE. The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Lithuania or the Eurosystem. 2 © Lietuvos bankas, 2019 Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged. -

Envacc Aug08

WISTA AUGUST 2008 From the Desk of Chairman Environment Accounting: Part 13 - 20 Leaders of Group of Eight (G8) met in Toyako, Japan, in July 2008. Apart from discussions on oil prices, world energy situation, IPR, their deliberations revolved around environment and climate change. The summary statement issued at the end of the summit acknowledged the role each of the G8 countries need to implement in order to achieve absolute reduction in emissions. Though the leaders agreed on a goal of 50% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2050, no detailed plans for working towards that goal were suggested. As such, it is generally felt that G8 summit has not been able to deliver enough and the results fall short of meeting the interlinked global challenges of energy security and climate change. The Special Feature in the present issue of WISTA: Environment Accounting gives a gist of G8 deliberations, specifically concerning climate change, as also comments by stakeholders on the outcome of the summit. It is surmised that if early actions for reducing GHG emissions are not taken, it would severely impact climate change. The ‘Perspective’ deals with carbon trading and the business opportunity it holds for India and other developing countries. Since many of the developed countries are lagging behind their Kyoto commitments, with the right strategies and approach, India could reap much benefits out of carbon trading. However, it is imperative that it should implement international transaction laws, proper regulatory mechanisms, and develop expertise and methodology of certification process. High oil prices and the ever rising demand for energy have spurred research to develop viable ways to produce biodiesel from agricultural sources, particularly from algae.