Why Should We Learn from the Barbarians? : the Concept of Westerners As Barbarians and the Translation of Western Works in the Modernization of China in the Late Qing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Poetry of the Nineteenth Century

“Modern” Science and Technology in “Classical” Chinese Poetry of the Nineteenth Century J. D. Schmidt 㕥⎱䐆 University of British Columbia This paper is dedicated to the memory of Prof. Daniel Bryant (1942-2014), University of Victoria, a great scholar and friend. Introduction This paper examines poetry about science and technology in nineteenth- century China, not a common topic in poetry written in Classical Chinese, much less in textbook selections of classical verse read in high school and university curricula in China. Since the May Fourth/New Culture Movement from the 1910s to the 1930s, China’s literary canon underwent a drastic revision that consigned a huge part of its verse written after the year 907 to almost total oblivion, while privileging more popular forms from after that date that are written in vernacular Chinese, such as drama and novels.1 The result is that today most Chinese confine their reading of poetry in the shi 娑 form to works created before the end of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), missing the rather extensive body of verse about scientific and technological subjects that began in the Song Dynasty (960-1278), largely disappeared in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), and then flourished as never before in the late Qing period (1644-1912). Except for a growing number of specialist scholars in China, very few Chinese readers have explored the poetry of the nineteenth century—in my opinion, one of the richest centuries in classical verse— thinking that the writing of this age is dry and derivative. Such a view is a product of the culture wars of the early twentieth century, but the situation has not been helped by the common name given to the most important literary group of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Qing Dynasty Song School (Qingdai Songshi pai 㶭ẋ⬳娑㳦), a term which suggests that its poetry is imitative of earlier authors, particularly those of the Song Dynasty. -

Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881

China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 The East India Company’s steamship Nemesis and other British ships engaging Chinese junks in the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841, during the first opium war. (British Library) ABOUT THE ARCHIVE China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 is digitised from the FO 17 series of British Foreign Office Files—Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence before 1906, China— held at the National Archives, UK, providing a vast and significant primary source for researching every aspect of Chinese-British relations during the nineteenth century, ranging from diplomacy to trade, economics, politics, warfare, emigration, translation and law. This first part includes all content from FO 17 volumes 1–872. Source Library Number of Images The National Archives, UK Approximately 532,000 CONTENT From Lord Amherst’s mission at the start of the nineteenth century, through the trading monopoly of the Canton System, and the Opium Wars of 1839–1842 and 1856–1860, Britain and other foreign powers gradually gained commercial, legal, and territorial rights in China. Imperial China and the West provides correspondence from the Factories of Canton (modern Guangzhou) and from the missionaries and diplomats who entered China in the early nineteenth century, as well as from the envoys and missions sent to China from Britain and the later legation and consulates. The documents comprising this collection include communications to and from the British legation, first at Hong Kong and later at Peking, and British consuls at Shanghai, Amoy (Xiamen), Swatow (Shantou), Hankow (Hankou), Newchwang (Yingkou), Chefoo (Yantai), Formosa (Taiwan), and more. -

Special Issue Taiwan and Ireland In

TAIWAN IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE Taiwan in Comparative Perspective is the first scholarly journal based outside Taiwan to contextualize processes of modernization and globalization through interdisciplinary studies of significant issues that use Taiwan as a point of comparison. The primary aim of the Journal is to promote grounded, critical, and contextualized analysis in English of economic, political, societal, and environmental change from a cultural perspective, while locating modern Taiwan in its Asian and global contexts. The history and position of Taiwan make it a particularly interesting location from which to examine the dynamics and interactions of our globalizing world. In addition, the Journal seeks to use the study of Taiwan as a fulcrum for discussing theoretical and methodological questions pertinent not only to the study of Taiwan but to the study of cultures and societies more generally. Thereby the rationale of Taiwan in Comparative Perspective is to act as a forum and catalyst for the development of new theoretical and methodological perspectives generated via critical scrutiny of the particular experience of Taiwan in an increasingly unstable and fragmented world. Editor-in-chief Stephan Feuchtwang (London School of Economics, UK) Editor Fang-Long Shih (London School of Economics, UK) Managing Editor R.E. Bartholomew (LSE Taiwan Research Programme) Editorial Board Chris Berry (Film and Television Studies, Goldsmiths College, UK) Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao (Sociology and Civil Society, Academia Sinica, Taiwan) Sung-sheng Yvonne Chang (Comparative Literature, University of Texas, USA) Kent Deng (Economic History, London School of Economics, UK) Bernhard Fuehrer (Sinology and Philosophy, School of Oriental and African Studies, UK) Mark Harrison (Asian Languages and Studies, University of Tasmania, Australia) Bob Jessop (Political Sociology, Lancaster University, UK) Paul R. -

Kaiming Press and the Cultural Transformation of Republican China

PRINTING, READING, AND REVOLUTION: KAIMING PRESS AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF REPUBLICAN CHINA BY LING A. SHIAO B.A., HEFEI UNITED COLLEGE, 1988 M.A., PENNSYVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, 1993 M.A., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 1996 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AT BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2009 UMI Number: 3370118 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform 3370118 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 © Copyright 2009 by Ling A. Shiao This dissertation by Ling A. Shiao is accepted in its present form by the Department of History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date W iO /L&O^ Jerome a I Grieder, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date ^)u**u/ef<2coy' Richard L. Davis, Reader DateOtA^UT^b Approved by the Graduate Council Date w& Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School in Ling A. -

The Circulation and Interpretation of Taiping Depositions

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses Undergraduate Research Spring 5-17-2019 A War of Words: The irC culation and Interpretation of Taiping Depositions Jordan Weinstock Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/undergrad_etd Part of the Asian History Commons Recommended Citation Weinstock, Jordan, "A War of Words: The irC culation and Interpretation of Taiping Depositions" (2019). Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses. 15. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/undergrad_etd/15 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A War of Words: The Circulation and Interpretation of Taiping Depositions By Jordan Weinstock A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Honors in History In the College of Arts and Sciences Washington University Advisor: Steven B. Miles April 1 2019 © Copyright by Jordan Weinstock, 2019. All rights reserved. Abstract: On November 18, 1864, the death knell of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was rung. Hong Tiangui Fu had been killed. Hong, divine leader of the once nascent kingdom and son of the Heavenly Kingdom’s founder, was asked to confess before his execution, making him one of the last figures to speak directly on behalf of the Qing’s most formidable opposition. The movement Hong had inherited was couched in anti-Manchu sentiment, pseudo-Marxist thought, and a distinct, unorthodox, Christian vision. -

Bannerman and Townsman: Ethnic Tension in Nineteenth-Century Jiangnan

Bannerman and Townsman: Ethnic Tension in Nineteenth-Century Jiangnan Mark Elliott Late Imperial China, Volume 11, Number 1, June 1990, pp. 36-74 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/late.1990.0005 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/late/summary/v011/11.1.elliott.html Access Provided by Harvard University at 02/16/13 5:36PM GMT Vol. 11, No. 1 Late Imperial ChinaJune 1990 BANNERMAN AND TOWNSMAN: ETHNIC TENSION IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY JIANGNAN* Mark Elliott Introduction Anyone lucky enough on the morning of July 21, 1842, to escape the twenty-foot high, four-mile long walls surrounding the city of Zhenjiang would have beheld a depressing spectacle: the fall of the city to foreign invaders. Standing on a hill, looking northward across the city toward the Yangzi, he might have decried the masts of more than seventy British ships anchored in a thick nest on the river, or perhaps have noticed the strange shapes of the four armored steamships that, contrary to expecta- tions, had successfully penetrated the treacherous lower stretches of China's main waterway. Might have seen this, indeed, except that his view most likely would have been screened by the black clouds of smoke swirling up from one, then two, then three of the city's five gates, as fire spread to the guardtowers atop them. His ears dinned by the report of rifle and musket fire and the roar of cannon and rockets, he would scarcely have heard the sounds of panic as townsmen, including his own relatives and friends, screamed to be allowed to leave the city, whose gates had been held shut since the week before by order of the commander of * An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Manchu Studies (Manzokushi kenkyùkai) at Meiji University, Tokyo, in November 1988. -

Copyright by James Joshua Hudson 2015

Copyright by James Joshua Hudson 2015 The Dissertation Committee for James Joshua Hudson Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: River Sands/Urban Spaces: Changsha in Modern Chinese History Committee: Huaiyin Li, Supervisor Mark Metzler Mary Neuburger David Sena William Hurst River Sands/Urban Spaces: Changsha in Modern Chinese History by James Joshua Hudson, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2015 Dedication For my good friend Hou Xiaohua River Sands/Urban Spaces: Changsha in Modern Chinese History James Joshua Hudson, PhD. The University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Huaiyin Li This work is a modern history of Changsha, the capital city of Hunan province, from the late nineteenth to mid twentieth centuries. The story begins by discussing a battle that occurred in the city during the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), a civil war that erupted in China during the mid nineteenth century. The events of this battle, but especially its memorialization in local temples in the years following the rebellion, established a local identity of resistance to Christianity and western imperialism. By the 1890’s this culture of resistance contributed to a series of riots that erupted in south China, related to the distribution of anti-Christian tracts and placards from publishing houses in Changsha. During these years a local gentry named Ye Dehui (1864-1927) emerged as a prominent businessman, grain merchant, and community leader. -

The Incompetence of Qing Dynasty Officials in the Opium Wars, and the Consequences of Defeat

An Indefensible Defense: The Incompetence of Qing Dynasty Officials in the Opium Wars, and the Consequences of Defeat DANIEL CONE The Opium Wars were small scale wars fought with global implications. With fewer than five thousand troops and twenty naval vessels the British were able to win the First Opium War, allowing them to rewrite trade laws that were demonstrably unfair to the Chinese. After losing the First Opium War, the Qing Dynasty then had to deal with the Taiping Rebellion (caused in part by anti- foreign sentiment sprung from the Opium War) and a subsequent Second Opium War, which created more unequal trade stipulations. The Manchus and the British had very different militaries, as “Britain experienced an industrial revolution that produced military technology far beyond that of the Qing forces,” writes Peter Worthing.1 While the Manchus would almost certainly be defeated by the British in an open, “fair fight,” there are many other ways of engaging an enemy while maintaining a tactical advantage. This is especially true when fighting an invading force, as the Manchus could utilize defensive structures to their advantage. According to the traditionalist view, the Manchus could not have competed with such a superior force,2 but I contend it was the incompetency of Qing officials, not the superiority of European warfare, that caused the Qing Dynasty to capitulate. Qing officials anticipated an armed conflict would be necessary to halt the importation of British opium, but the Manchus vastly underestimated the foe they were to face. The preparations made before the invasion were underfunded, underutilized, and most importantly undermanned; often leaving local provinces to fight without any assistance. -

![The East Spread of Western Learning and Conditions in China: Notes on "Various Books"] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1979), Pp](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1029/the-east-spread-of-western-learning-and-conditions-in-china-notes-on-various-books-tokyo-iwanami-shoten-1979-pp-1751029.webp)

The East Spread of Western Learning and Conditions in China: Notes on "Various Books"] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1979), Pp

Seiqaku tozen to Chugoku jijo: 'zassho sakki' ~ $ * i!Wi c cp ~ "$ 'tw: ,- ~t w: ~ fL d~ [The East Spread of western Learning and Conditions in China: Notes on "Various Books"] (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1979), pp. 31-58. Masuda Wataru :1:~ EB~ PART 2 Translated by Joshua A. Fogel University of California, Santa Barbara 5. The Haiguo tuzhi M~~;s; [Illustrated Gazetteer of the Sea Kingdoms] and Shengwu II ~JiU2 [Reoord of August {Manohu} Military Aohievements] by Wei Yuan ~iIffi (1794-1856) In Japan, the most stimulating and influential Chinese-language work in the field of world geography and topography was doubtless the Haiquo tuzhi. That is to say, the Haiguo tuzhi was not simply a work that conveyed knowledge of geography and topography. It was also a study of defensive military strategy and tactics in the face of the foreign powers then exerting considerable military pressure on East Asia, including gunboats and artillery. Wei Yuan wrote the Haiguo tuzhi from an indignation borne of China's defeat in the Opium War and with that experience as an object lesson. Because of the con crete quality of their arguments concerning naval defenses, the Haiguo tuzhi and the Shengwu ii, written at about the same time, were packed with suggestions for Japan at that time. This was a time when naval defense was being actively debated in Japan, spurred by the arrival of vessels, commanded by Admiral Matthew Perry (1794-1858) and Admiral Putiatin (1803-83), along the Japanese coast and by the stringent diplomatic posture assumed by Townsend Harris (1804-78).1 The Shengwu ii was, for the most part, a chronicle to that point in time of the Qing dynasty's "august" (sheng ~ ) military victories in which the rebellions of border peoples, gangs of pirate, or rebel lious religious insurgents had been suppressed. -

Communication, Empire, and Authority in the Qing Gazette

COMMUNICATION, EMPIRE, AND AUTHORITY IN THE QING GAZETTE by Emily Carr Mokros A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland June, 2016 © 2016 Emily Carr Mokros All rights Reserved Abstract This dissertation studies the political and cultural roles of official information and political news in late imperial China. Using a wide-ranging selection of archival, library, and digitized sources from libraries and archives in East Asia, Europe, and the United States, this project investigates the production, regulation, and reading of the Peking Gazette (dibao, jingbao), a distinctive communications channel and news publication of the Qing Empire (1644-1912). Although court gazettes were composed of official documents and communications, the Qing state frequently contracted with commercial copyists and printers in publishing and distributing them. As this dissertation shows, even as the Qing state viewed information control and dissemination as a strategic concern, it also permitted the free circulation of a huge variety of timely political news. Readers including both officials and non-officials used the gazette in order to compare judicial rulings, assess military campaigns, and follow court politics and scandals. As the first full-length study of the Qing gazette, this project shows concretely that the gazette was a powerful factor in late imperial Chinese politics and culture, and analyzes the close relationship between information and imperial practice in the Qing Empire. By arguing that the ubiquitous gazette was the most important link between the Qing state and the densely connected information society of late imperial China, this project overturns assumptions that underestimate the importance of court gazettes and the extent of popular interest in political news in Chinese history. -

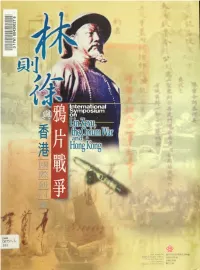

Internatioanl Symposium on Lin Zexu, the Opium War and Hong Kong = Lin Zexu, Ya Pian Zhan Zheng Yu Xianggang Guo Ji Yan Tao

c * Jointly organized by ft W (# Hong Kong Museum of Hislory. Pro\ isional Urban Council Hit^fr Lin Ze.\u Koundalion Association of Chinese Histonans M -f: ' I International Symposium on Lin Zexu, the Opium War and Hong Kong ate: 18-19.12.98 = 'Lin Zexu and the Opium War " Exhibitii Date of Opening: 1 ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( 1' ( Canada-Hong Kong Resource Centre 1 Spadioa Crescent, Rm. Ill • Toronto, Canada • M5S 1A1 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Multicultural Canada; University of Toronto Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/linzexuyapianzhaOOhong ) ) #^ List of Parti cipants ( ( Listed in alphabetical order) Mainland: 1. Prof. Dai Xueji (Institute of Social Sciences, Fujian) 2. Prof. Deng Kaisong (Office of Hong Kong and Macau History, Institute of Social Sciences, Guangdong 3. Prof. Hao Guiyuan (Institute of World History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) 4. M Prof. Huang Shunli (Department of History, University of Xiamen) 5. Prof. Jiang Dachun (Institute of Modern History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) 6. Prof. Lai Xinxia (Local Document Research Institute, Nankai University) 7. I Prof. Li Hongsheng (University of Social Sciences, Guangdong I History Society, Guangdong 8. Prof. Lin Qingyuan (Department of History, Fujian Normal University) 9. Prof. Lin Zidong (Federation of Social Sciences, Fujian) 10. Prof. Ling Qing (Lin Zexu Foundation) 11. Prof. Liu Shuyong (Institute of Modem History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) 12. Prof. Wang Rufeng (Department of History, The People's University of China) 13. Prof. Xiao Zhizhi (Academy of History and Culture, University of Wuhan) 14. Jl Prof. Yang Guozhen (Institute of Historical Research, University of Xiamen) 15. -

Appropriating the West in Late Qing and Early Republican China / Theodore Huters

Tseng 2005.1.17 07:55 7215 Huters / BRINGING THE WORLD HOME / sheet 1 of 384 Bringing the World Home Tseng 2005.1.17 07:55 7215 Huters / BRINGING THE WORLD HOME / sheet 2 of 384 3 of 384 BringingÕ the World HomeÕ Appropriating the West in Late Qing 7215 Huters / BRINGING THE WORLD HOME / sheet and Early Republican China Theodore Huters University of Hawai‘i Press Honolulu Tseng 2005.1.17 07:55 © 2005 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Huters, Theodore. Bringing the world home : appropriating the West in late Qing and early Republican China / Theodore Huters. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8248-2838-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Chinese literature—20th century—History and criticism. 2. Chinese literature—20th century—Western influences. I. Title. PL2302.H88 2005 895.1’09005—dc22 2004023334 University of Hawai‘i Press books are printed on acid- free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. The open-access ISBN for this book is 978-0-8248-7401-8. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The open-access version of this book is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NC-ND 4.0), which means that the work may be freely downloaded and shared for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author.