ENLIGHTENED and EXOTIC Ralph P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

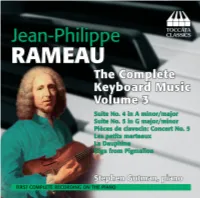

Toccata Classics TOCC0052 Notes

RAMEAU ON THE PIANO, VOLUME THREE 1 by Graham Sadler The two suites recorded on this disc are from the Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin of 1729 or 1730, Rameau’s final collection of solo keyboard music.2 Like those of his Pièces de clavessin (1724), they are contrasted both in tonality and character. The Suite in A minor and major is dominated by dances and includes only three character pieces, whereas the Suite in G major and minor consists almost exclusively of pieces with character titles. In its make-up if not its style, the latter thus follows the example of François Couperin, whose first three books of pièces de clavecin (1713, 1717 and 1722) had established the vogue for descriptive pieces. In that sense, Rameau may be regarded as somewhat conservative in devoting half of his two mature solo collections to suites of the more traditional type. Suite No. 4 in A minor and major Conservative they may be, but the dance movements of the Nouvelles suites are among the most highly P developed in the repertory, the first two particularly so. The Allemande 1 unfolds with an effortless grace, its unerring sense of direction reinforced by the many sequential passages. At the end of both sections, the duple semiquaver motion gives way unexpectedly to triplet motion, providing a memorable ‘rhyme’ to the two parts of the movement. The Courante 2, more than twice as long as its predecessors in Rameau’s output, displays a technical sophistication without parallel in the clavecin repertory. Three themes interlock in mainly three- part counterpoint – a bold motif in rising fourths, and two accompanying figures in continuous quavers, the one in sinuous stepwise movement, the other comprising cascading arpeggios. -

Le Monde Galant

The Juilliard School presents Le Monde Galant Juilliard415 Nicholas McGegan, Director Recorded on May 1, 2021 | Peter Jay Sharp Theater FRANCE ANDRÉ CAMPRA Ouverture from L’Europe Galante (1660–1744) SOUTHERN EUROPE: ITALY AND SPAIN JEAN-MARIE LECLAIR Forlane from Scylla et Glaucus (1697–1764) Sicilienne from Scylla et Glaucus CHRISTOPH WILLIBALD GLUCK Menuet from Don Juan (1714–87) MICHEL RICHARD DE LALANDE Chaconne légère des Maures from Les Folies (1657–1726) de Cardenio CHARLES AVISON Con Furia from Concerto No. 6 in D Major, (1709-70) after Domenico Scarlatti CELTIC LANDS: SCOTLAND AND IRELAND GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN L’Eccossoise from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D19 (1681–1767) NATHANIEL GOW Largo’s Fairy Dance: The Fairies Advancing and (1763–1831) Fairies Dance Cullen O’Neil, Solo Cello TELEMANN L’Irlandoise from Overture in D Minor, TVW55:d2 EASTERN EUROPE: POLAND, BOHEMIA, AND HUNGARY ARR. TELEMANN Danse de Polonie No. 4, TWV45 Polonaise from Concerto Polonois, TWV43:G7 Danse de Polonie No. 1, TWV45 La Hanaquoise, TWV55:D3 TRADITIONAL Three 18th-century Hanák folk tunes RUSSIA TELEMANN Les Moscovites from Overture in B-flat Major, TWV55:B5 Program continues 1 EUROPE DREAMS OF THE EAST: THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE TELEMANN Les Janissaries from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D17 Mezzetin en turc from Overture-Burlesque in B-flat Major, TWV55:B8 PERSIA AND CHINA JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU Air pour Borée from Les Indes galantes (1683–1764) Premier Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Seconde Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Entrée des Chinois -

Les Talens Lyriques the Ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, Which Takes Its

Les Talens Lyriques The ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, which takes its name from the subtitle of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Les Fêtes d’Hébé (1739), was formed in 1991 by the harpsichordist and conductor Christophe Rousset. Championing a broad vocal and instrumental repertoire, ranging from early Baroque to the beginnings of Romanticism, the musicians of Les Talens Lyriques aim to throw light on the great masterpieces of musical history, while providing perspective by presenting rarer or little known works that are important as missing links in the European musical heritage. This musicological and editorial work, which contributes to its renown, is a priority for the ensemble. Les Talens Lyriques perform to date works by Monteverdi (L'Incoronazione di Poppea, Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, L’Orfeo), Cavalli (La Didone, La Calisto), Landi (La Morte d'Orfeo), Handel (Scipione, Riccardo Primo, Rinaldo, Admeto, Giulio Cesare, Serse, Arianna in Creta, Tamerlano, Ariodante, Semele, Alcina), Lully (Persée, Roland, Bellérophon, Phaéton, Amadis, Armide, Alceste), Desmarest (Vénus et Adonis), Mondonville (Les Fêtes de Paphos), Cimarosa (Il Mercato di Malmantile, Il Matrimonio segreto), Traetta (Antigona, Ippolito ed Aricia), Jommelli (Armida abbandonata), Martin y Soler (La Capricciosa corretta, Il Tutore burlato), Mozart (Mitridate, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Così fan tutte, Die Zauberflöte), Salieri (La Grotta di Trofonio, Les Danaïdes, Les Horaces, Tarare), Rameau (Zoroastre, Castor et Pollux, Les Indes galantes, Platée, Pygmalion), Gluck -

Rameau's Imaginary Monsters: Knowledge, Theory, And

Rameau's Imaginary Monsters: Knowledge, Theory, and Chromaticism in Hippolyte et Aricie Author(s): Charles Dill Source: Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 55, No. 3 (Winter 2002), pp. 433- 476 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the American Musicological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jams.2002.55.3.433 . Accessed: 04/09/2014 11:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and American Musicological Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the American Musicological Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.104.46.206 on Thu, 4 Sep 2014 11:26:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Rameau's Imaginary Monsters: Knowledge, Theory, and Chromaticism in Hippolyte etAricie CHARLES DILL dialectic existed at the heart of Enlightenment thought, a tension that sutured instrumentalreason into place by offering the image of its irra- JL A1tional other. Embedded within the rationalorder of encyclopedicen- terpriseslay the threat posed by superstition,both religious and unlettered; contained and controlled by the solid foundations of social contractswas the disturbing image of chaos, evoked musically by Jean-FeryRebel and Franz Joseph Haydn, and among the nobly formed figures of humankind and nature there lurked deformity and aberration,there lurked the monster. -

Les Indes Galantes Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764)

Les Indes Galantes Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) Opéra ballet composé d'un prologue et de quatre entrées. créé à l’Académie Royale de Musique le 23 août 1735, sur un livret de Louis Fuzelier Les quatre voyages des Indes. L’œuvre s’est tout d’abord intitulée: “Les Victoires Galantes”. On y témoignait du pouvoir de l’amour. Dans un second temps, les auteurs préférent “Les Indes Galantes”. Ils rendent ainsi hommage à la magie de l’exotisme et la force de son imaginaire. Notez que les Indes étaient alors orientales, les pays d'Asie, et occidentales, les Amériques. La création de l’œuvre, un des tout premiers opéras de Rameau puisque seul Hippolyte et Aricie le précède, remporte un succès mitigé. Les auteurs la reprennent, la corrigent, l’adaptent, la complètent. Tant et si bien que pas moins de 16 versions du livret vont voir le jour du temps de Rameau ainsi que 8 versions de la partition. L’ordre des tableaux, des airs, des danses évolueront constamment au gré des critiques, des envies et des nécessités. Prologue Hébé, déesse de la jeunesse est tour à tour sollicitée par l’Amour et par Bellone, déesse de la guerre, qui l’une et l’autre veulent ses faveurs. Indécise et tiraillée entre les attraits de la gloire et ceux d'une paisible idylle, la jeunesse se voit proposer d’embarquer pour les Indes Galantes.. Le Turc généreux Les personnages: Osman Grand Vizir (basse) Emilie Esclave provençale d’Osman (soprano) Valère Marin, amant d’Emilie (haute-contre) Chœur des Matelots et des Matelottes Ce qui s'était passé à l'époque: Les récits de voyage, de Tavernier, Thévenot ou Chardin, les traductions de littérature orientale et surtout "Les Mille et une Nuits" (1704-1717) révèlent aux lecteurs de l’époque, un univers intrigant par l’étrangeté et le charme de ses mœurs. -

Regards Sur Le Siècle Musical De Rameau

De quelques révolutions françaises : regards sur le siècle musical de Rameau Pierre Saby Monseigneur, il y a dans cet opéra assez de musique pour en faire dix1. Ainsi, en 1733, André Campra2, au crépuscule de sa carrière, s’adressait-il au prince de Conti, après la création à l’Académie royale de musique de Hippolyte et Aricie, première des tragédies en musique de Jean-Philippe Rameau, lui-même alors âgé de cinquante ans. Ce que le maître de la génération finissante soulignait, dans une formule où se mêlent admiration et réserve, fit l’objet d’un commentaire clairvoyant une trentaine d’années plus tard, un mois après la mort de Rameau, dans le Mercure de France d’octobre 17643 : C’est ici l’époque de la révolution qui se fit dans la Musique & de ses nouveaux progrès en France. […] La partie du Public qui ne juge & ne décide que par impression, fut d’abord étonnée d’une Musique bien plus chargée & plus fertile en images, que l’on avoit coutume d’en entendre au Théâtre. On goûta néanmoins ce nouveau genre et on finit par l’applaudir4. On finit par l’applaudir, certes. Cela n’alla pas sans controverse, cependant. Outre le fait que Rameau, confronté à l’incapacité où se trouvaient quelques chanteurs (au moins) d’exécuter correctement ce qu’il avait écrit, se vit contraint, au cours des répétitions, de renoncer à la version initiale du « Trio des Parques » au deuxième acte de l’ouvrage, l’apparition de Hippolyte et Aricie sur la scène de l’opéra parisien déclencha une véritable querelle, annonciatrice, quoique rétrospectivement on puisse la juger modérée, de celles dont devait se nourrir jusqu’à la fin du siècle l’histoire du théâtre lyrique français. -

Le Monde Galant

The Juilliard School presents Le Monde Galant Juilliard415 Nicholas McGegan, Director Recorded on May 1, 2021 Peter Jay Sharp Theater France ANDRÉ CAMPRA (1660–1744) Ouverture from L’Europe Galante Southern Europe: Italy and Spain JEAN-MARIE LECLAIR (1697–1764) Forlane from Scylla et Glaucus Sicilienne from Scylla et Glaucus CHRISTOPH WILLIBALD GLUCK (1714–87) Menuet from Don Juan MICHEL RICHARD DE LALANDE (1657–1726) Chaconne légère des Maures from Les Folies de Cardenio CHARLES AVISON (1709-70) Con Furia from Concerto No. 6 in D Major, after Domenico Scarlatti Celtic Lands: Scotland and Ireland GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN (1681–1767) L’Eccossoise from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D19 NATHANIEL GOW (1763–1831) Largo’s Fairy Dance: The Fairies Advancing and Fairies Dance Cullen O’Neil, Solo Cello TELEMANN L’Irlandoise from Overture in D Minor, TVW55:d2 Eastern Europe: Poland, Bohemia, and Hungary ARR. TELEMANN Danse de Polonie No. 4, TWV45 Polonaise from Concerto Polonois, TWV43:G7 Danse de Polonie No. 1, TWV45 La Hanaquoise, TWV55:D3 TRADITIONAL Three 18th-century Hanák folk tunes Russia TELEMANN Les Moscovites from Overture in B-flat Major, TWV55:B5 Europe Dreams of the East: The Ottoman Empire TELEMANN Les Janissaries from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D17 Mezzetin en turc from Overture-Burlesque in B-flat Major, TWV55:B8 Persia and China JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU (1683–1764) Air pour Borée from Les Indes galantes Premier Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Seconde Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Entrée des Chinois from Les Paladins -

Rameau, Jean-Philippe

Rameau, Jean-Philippe (b Dijon, bap. 25 Sept 1683; d Paris, 12 Sept 1764). French composer and theorist. He was one of the greatest figures in French musical history, a theorist of European stature and France's leading 18th-century composer. He made important contributions to the cantata, the motet and, more especially, keyboard music, and many of his dramatic compositions stand alongside those of Lully and Gluck as the pinnacles of pre-Revolutionary French opera. 1. Life. 2. Cantatas and motets. 3. Keyboard music. 4. Dramatic music. 5. Theoretical writings. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY GRAHAM SADLER (1–4, work-list, bibliography) THOMAS CHRISTENSEN (5, bibliog- raphy) 1. Life. (i) Early life. (ii) 1722–32. (iii) 1733–44. (iv) 1745–51. (v) 1752–64. (i) Early life. His father Jean, a local organist, was apparently the first professional musician in a family that was to include several notable keyboard players: Jean-Philippe himself, his younger brother Claude and sister Catherine, Claude's son Jean-François (the eccentric ‘neveu de Rameau’ of Diderot's novel) and Jean-François's half-brother Lazare. Jean Rameau, the founder of this dynasty, held various organ appointments in Dijon, several of them concurrently; these included the collegiate church of St Etienne (1662–89), the abbey of StSt Bénigne (1662–82), Notre Dame (1690–1709) and St Michel (1704–14). Jean-Philippe's mother, Claudine Demartinécourt, was a notary's daughter from the nearby village of Gémeaux. Al- though she was a member of the lesser nobility, her family, like that of her husband, included many in humble occupations. -

Score Review: Rameau, Jean-Philippe. "Les Indes Galantes" and "Daphnis Et Eglé." Geoffrey Burgess

Performance Practice Review Volume 22 | Number 1 Article 3 Score Review: Rameau, Jean-Philippe. "Les Indes galantes" and "Daphnis et Eglé." Geoffrey Burgess Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Performance Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Burgess, Geoffrey (2017) "Score Review: Rameau, Jean-Philippe. "Les Indes galantes" and "Daphnis et Eglé."," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 22: No. 1, Article 3. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.201722.01.03 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol22/iss1/3 This Score Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Score review: Rameau, Jean-Philippe. Les Indes galantes: Symphonies, RCT 44 ed. Sylvie Bouissou, ed. no. BA 7568. Paris: Société Jean-Philippe Rameau; international distributor: Bärenreiter, 2017; Rameau, Jean-Philippe. Daphnis et Eglé, RCT 34, ed. Érik Kocevar, piano reduction François Saint-Yves. Paris: Société Jean-Philippe Rameau; international distributor: Bärenreiter, 2017. Geoffrey Burgess The absence of a reliable edition of the instrumental music and dances from Rameau’s popular Les Indes galantes has long been decried by conductors and ensembles. Up to now, orchestras have had to cobble together their own edition—anything from a custom- edited score taken directly from primary sources to a cut-and-paste of Paul Dukas’s creative reorchestration in the Œuvres complètes. This new score is a welcome attempt to fill this gap and aims to satisfy the demands of both scholars and performers. -

Download Booklet

LIGHT DIVINE INTRODUCTION 1 Concerto in F, HWV 331 George Frideric Handel, [4.18] Aksel and I first met in the Oslo Chamber Music Arr. Mark Bennett Festival in 2016. Aksel had already recorded his 2 Eternal Source of Light Divine, HWV 74 George Frideric Handel [3.10] first album in the UK with the Orchestra of the Age 3 Passacaille from Sonata in G, Op. 5, No. 5, HWV 399 George Frideric Handel [4.54] of Enlightenment and had performed some of the Arr. Mark Bennett more well known music for soprano and trumpet. 4 What Passion Cannot Music Raise And Quell, HWV 76 George Frideric Handel [8.18] 5 Alla caccia (Diana cacciatrice), HWV 79 George Frideric Handel [6.25] We worked together on a few more projects and Arr. Mark Bennett continued to play these same pieces. A few months were - in Jar Kirke, Oslo, making it all happen. 6 Vien con nuova orribil guerra, from La Statira Tomaso Albinoni [5.33] later I was given some opportunities to direct and Despite the issues of summer holidays and Ornaments by Mark Bennett lead my own productions and I invited Aksel along. various summer festivals, it just all fell into 7 Ciaccona à 7 Philipp Jakob Rittler [4.58] place. It was a miracle. 8 Ritournelle, from Hippolyte et Aricie Jean-Philippe Rameau [1.50] I started to introduce new repertoire to Aksel Arr. Aareskjold/Bennett and he just seemed to thrive on this challenge. The MIN Ensemble, although a modern 9 Entrée d’Abaris, from Les Boréades Jean-Philippe Rameau [3.47] Projects with The Norwegian Radio Orchestra instrument group, were enthusiastic about my 0 Tristes apprêts, from Castor et Pollux Jean-Philippe Rameau [6.20] and the Oslo-based period instrument orchestra more early music approach. -

Transformation De L'autre Exotique Dans Les Indes Galantes De

Le Monde Français du Dix-Huitième Siècle Volume 5, Issue-numéro 1 2020 Transposition(s) and Confrontation(s) in the British Isles, in France and Northern America (1688-1815) Dirs. Pierre-François Peirano & Hélène Palma Transformation de l’autre exotique dans Les Indes galantes de Rameau et Fuzelier (1736) Catherine Gallouët Hobart & William Smith Colleges [email protected] DOI: 10.5206/mfds-ecfw.v5i1.10548 2 Transformation de l’autre exotique dans Les Indes galantes de Rameau et Fuzelier (1736), ou comment l’autre se construit sur la scène* Le 23 août 1735 se tient, à l’Académie Royale de Musique située au Palais Royal, la première représentation des Indes galantes,1 l’opéra-ballet de Jean-Philippe Rameau (musique) et Louis Fuzelier (livret), composé d’un « Prologue » et de deux « Entrées ». Devant l’accueil réservé du public, les auteurs refondent cette première version. Une nouvelle entrée, « Les sauvages » est ajoutée le 10 mars 1736. Cette version définitive comporte quatre entrées, Le « Turc Généreux », « Les Incas du Pérou », ainsi que « Les Fleurs. Fête persane ». Le compositeur en donne les raisons dans la « Préface » de l’édition Boivin de 1736 : Le public ayant paru moins satisfait des scènes des Indes galantes, je n’ai pas cru devoir appeler de son jugement ; et c’est pour cette raison que je ne lui présente ici que les symphonies entremêlées des airs chantants, ariettes, récitatifs mesurés, duos, trios, quatuors et chœurs, tant du prologue que des trois premières entrées, qui font en tout plus de quatre-vingts morceaux détachés, dont j’ai formé quatre grands concerts en différents tons.2 Rameau adopte la nouvelle formule de l’opéra-ballet où la musique l’emporte sur le récitatif rendu « mesuré », où le divertissement se déploie en « différents tons » qui chacun distingue une entrée, en Turquie et en Perse, au Pérou et en Amérique du Nord, et transforment l’opéra-ballet en panorama musical du monde exotique. -

�'/ Ï U /" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> Les Fetes D'hebe "> �'/ Ï U /

JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU s s LES FETES D'HEBE "> '/ ï U / / QUII M LIA M CHRIS 1 IF Les Arts Florissants WILLIAM CHRISTIE W9LI.IAI/'« I HANDEL Orlando PfcCHINfcV >^ NOUVEAUTE WILLIAM CHRISTIE ET LES ARTS FLORISSANTS ENREGISTRENT EN EXCLUSIVITÉ POUR ERATO. ERATO JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU (1683-1764) LES FETES D'HEBs Es (1739) Opéra-ballet en trois actes sur un livret d'Antoine Gautier de Montdorge (version de concert) DISTRIBUTION Dessus Sarah Connolly Sophie Daneman Maryseult Wieczorek Haute-contre : Jean-Paul Fouchécourt Taille : Paul Agnew Basse : Luc Coadou Olivier Lallouette Matthieu Lécroart Laurent Slaars DECEMBRE 1996 BRUXELLES Palais des Beaux-Arts le 16 à20h00 LONDRES Barbican Centre le 18 à19h30 CAEN Théâtre de Caen le 20 à20h30 Avec le soutien de IA.F.A.A., Association Française dAction Artistique - Ministère des Affaires Etrangères Avec la participation du Ministère de la Culture, de la ville de Caen, du Conseil Régional de Basse-Normandie PECHINEY parraine Les Arts Florissants depuis 1990 LPRO 1996/64 RÔLES PROLOGUE FFébé : Sophie Daneman L'Amour : Sarah Connolly Momus : Paul Agnew PREMIERE ENTRÉE : LA POÉSIE Sapho . Sarah Connolly La Naïade. Sophie Daneman Le Ruisseau, Maryseult Wieczorek Paul Agnew Thélème. Jean-Paul Fouchécourt Alcée. Luc Coadou Hymas. Laurent Slaars Le Fleuve. Matthieu Lécroart DEUXIEME ENTREE : LA MUSIQUE Iphise : Sarah Connolly Une Lacédémonienne : Maryseult Wieczorek Lycurgue : Paul Agnew Tirtée : Olivier Lallouette TROISIÈME ENTRÉE : LA DANSE Eglé : Sophie Daneman Une Bergère : Maryseult Wieczorek Mercure