Jean Philippe-Rameau and the Corps Sonore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAMEAU LES BORÉADES Václav Luks MENU

RAMEAU LES BORÉADES Václav Luks MENU Tracklist Distribution L'œuvre Compositeur Artistes Synopsis Textes chantés L'Opéra Royal 1 MENU LES BORÉADES VOLUME 1 69'21 1 Ouverture 2'28 2 Menuet 0'44 3 Allegro 1'32 ACTE I 4 Scène 1 - Alphise et Sémire 3'19 Récits en duo et Airs d'Alphise «Suivez la chasse» Deborah Cachet, Caroline Weynants 5 Scène 2 - Borilée et les Précédents 0'29 Air et Récit de Borilée «La chasse à mes regards» Tomáš Šelc 6 Scène 3 - Calisis et les Précédents 2'08 Récit et Air de Calisis «À descendre en ces lieux» Deborah Cachet, Benedikt Kristjánsson 7 Scène 4 - Troupe travestie en Plaisirs et Grâces 0'35 Air de Calisis «Cette troupe aimable» Caroline Weynants, Benedikt Kristjánsson 8 Air gracieux (Ballet) 1'51 9 Air de Sémire «Si l'hymen a des chaines» – Caroline Weynants 0'40 10 Première Gavotte gracieuse 0'32 11 Deuxième Gavotte (Ballet) 0'46 12 Première Gavotte da capo (Ballet) 0'18 2 13 Air de Calisis «C'est dans cet aimable séjour» – Benedikt Kristjánsson 0'46 14 Rondeau vif (Ballet) – Caroline Weynants 2'23 15 Gavotte vive (Ballet) 0'51 16 Deuxième Gavotte (Ballet) 0'53 17 Ariette pour Alphise ou la Confidente (Sémire) «Un horizon serein» 7'37 Deborah Cachet ou Caroline Weynants 18 Contredanse en Rondeau (Ballet) 1'57 19 L'Ouverture pour Entracte ACTE II 20 Scène 1 - Abaris 2'25 Air d'Abaris «Charmes trop dangereux» Mathias Vidal 21 Scène 2 - Adamas et Abaris 0'31 Récit d'Adamas «J'aperçois ce mortel» Benoît Arnould 22 Air d'Adamas «Lorsque la lumière féconde» – Benoît Arnould 1'08 23 Récit d'Abaris et Adamas «Quelle -

Research on the History of Modern Acoustics François Ribac, Viktoria Tkaczyk

Research on the history of modern acoustics François Ribac, Viktoria Tkaczyk To cite this version: François Ribac, Viktoria Tkaczyk. Research on the history of modern acoustics. Revue d’Anthropologie des Connaissances, Société d’Anthropologie des Connaissances, 2019, Musical knowl- edge, science studies, and resonances, 13 (3), pp.707-720. 10.3917/rac.044.0707. hal-02423917 HAL Id: hal-02423917 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02423917 Submitted on 26 Dec 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. RESEARCH ON THE HISTORY OF MODERN ACOUSTICS Interview with Viktoria Tkaczyk, director of the Epistemes of Modern Acoustics research group at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin François Ribac S.A.C. | « Revue d'anthropologie des connaissances » 2019/3 Vol. 13, No 3 | pages 707 - 720 This document is the English version of: -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- François Ribac, « Recherche en histoire de l’acoustique moderne », Revue d'anthropologie -

Linear and Nonlinear Waves

Scholarpedia, 4(7):4308 www.scholarpedia.org Linear and nonlinear waves Graham W. Griffithsy and William E. Schiesser z City University,UK; Lehigh University, USA. Received April 20, 2009; accepted July 9, 2009 Historical Preamble The study of waves can be traced back to antiquity where philosophers, such as Pythagoras (c.560-480 BC), studied the relation of pitch and length of string in musical instruments. However, it was not until the work of Giovani Benedetti (1530-90), Isaac Beeckman (1588-1637) and Galileo (1564-1642) that the relationship between pitch and frequency was discovered. This started the science of acoustics, a term coined by Joseph Sauveur (1653-1716) who showed that strings can vibrate simultaneously at a fundamental frequency and at integral multiples that he called harmonics. Isaac Newton (1642-1727) was the first to calculate the speed of sound in his Principia. However, he assumed isothermal conditions so his value was too low compared with measured values. This discrepancy was resolved by Laplace (1749-1827) when he included adiabatic heating and cooling effects. The first analytical solution for a vibrating string was given by Brook Taylor (1685-1731). After this, advances were made by Daniel Bernoulli (1700-82), Leonard Euler (1707-83) and Jean d'Alembert (1717-83) who found the first solution to the linear wave equation, see section (3.2). Whilst others had shown that a wave can be represented as a sum of simple harmonic oscillations, it was Joseph Fourier (1768-1830) who conjectured that arbitrary functions can be represented by the superposition of an infinite sum of sines and cosines - now known as the Fourier series. -

Rameau Et L'opéra Comique

2020 HIPPOLYTE ET ARICIE HIPPOLYTE ET ARICIEJEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU 11, 14, 15, 18, 21, 22 NOVEMBRE 2020 1 Soutenu par Soutenu par AVEC L'AIMABLE AVEC LE SOUTIEN DE PARTENARIAT MÉDIA Madame Aline Foriel-Destezet, PARTICIPATION DE Grande Donatrice de l’Opéra Comique Spectacle capté les 15 et 18 novembre et diffusé ultérieurement. 2 HIPPOLYTETragédie lyrique en cinq actes de Jean-Philippe ET ARICIE Rameau. Livret de l’abbéer Pellegrin Créée à l’Académie royale de musique (Opéra) le 1 octobre 1733. Version de 1757 (sans prologue) avec restauration d’éléments des versions antérieures (1733 et 1742). Raphaël Pichon Direction musicale - Jeanne Candel Mise en scène -Lionel Gonzalez Dramaturgie et direction d’acteurs - Lisa Navarro DécorsPauline - Kieffer Costumes -César Godefroy Lumières - Yannick Bosc Collaboration aux mouvements - Ronan Khalil * Chef de chant - Valérie Nègre Assistante mise en scène -Margaux Nessi Assistante décorsNathalie - Saulnier Assistante costumes - Reinoud van Mechelen Hippolyte - Elsa Benoit SylvieAricie Brunet-Grupposo - Phèdre - Stéphane Degout Opéra Comique Thésée - Nahuel Di Pierro Production Opéra Royal – Château de Versailles Spectacles Neptune, Pluton -Eugénie Lefebvre Coproduction Diane - Lea Desandre Prêtresse de Diane, Chasseresse, Matelote, BergèreSéraphine - Cotrez © Édition Nicolas Sceaux 2007-2020 Œnone - Edwin Fardini Pygmalion. Tous droits réservés Constantin Goubet* re Tisiphone - Martial Pauliat* e 1 Parque - 3h entracte compris Virgile Ancely * 2 Parque,e Arcas - Durée estimée : 3 ParqueGuillaume - Gutierrez* Mercure - * MembresYves-Noël de Pygmalion Genod Iliana Belkhadra Introduction au spectacle Chantez Hippolyte Prologue - Leena Zinsou Bode-Smith (11, 15, 18 et 22 novembre) / et Aricie et Maîtrise Populaire de(14 l’Opéra et 21 novembre) Comique sont temporairement suspendues en raison de la des conditions sanitaires. -

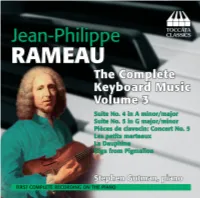

Toccata Classics TOCC0052 Notes

RAMEAU ON THE PIANO, VOLUME THREE 1 by Graham Sadler The two suites recorded on this disc are from the Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin of 1729 or 1730, Rameau’s final collection of solo keyboard music.2 Like those of his Pièces de clavessin (1724), they are contrasted both in tonality and character. The Suite in A minor and major is dominated by dances and includes only three character pieces, whereas the Suite in G major and minor consists almost exclusively of pieces with character titles. In its make-up if not its style, the latter thus follows the example of François Couperin, whose first three books of pièces de clavecin (1713, 1717 and 1722) had established the vogue for descriptive pieces. In that sense, Rameau may be regarded as somewhat conservative in devoting half of his two mature solo collections to suites of the more traditional type. Suite No. 4 in A minor and major Conservative they may be, but the dance movements of the Nouvelles suites are among the most highly P developed in the repertory, the first two particularly so. The Allemande 1 unfolds with an effortless grace, its unerring sense of direction reinforced by the many sequential passages. At the end of both sections, the duple semiquaver motion gives way unexpectedly to triplet motion, providing a memorable ‘rhyme’ to the two parts of the movement. The Courante 2, more than twice as long as its predecessors in Rameau’s output, displays a technical sophistication without parallel in the clavecin repertory. Three themes interlock in mainly three- part counterpoint – a bold motif in rising fourths, and two accompanying figures in continuous quavers, the one in sinuous stepwise movement, the other comprising cascading arpeggios. -

Le Monde Galant

The Juilliard School presents Le Monde Galant Juilliard415 Nicholas McGegan, Director Recorded on May 1, 2021 | Peter Jay Sharp Theater FRANCE ANDRÉ CAMPRA Ouverture from L’Europe Galante (1660–1744) SOUTHERN EUROPE: ITALY AND SPAIN JEAN-MARIE LECLAIR Forlane from Scylla et Glaucus (1697–1764) Sicilienne from Scylla et Glaucus CHRISTOPH WILLIBALD GLUCK Menuet from Don Juan (1714–87) MICHEL RICHARD DE LALANDE Chaconne légère des Maures from Les Folies (1657–1726) de Cardenio CHARLES AVISON Con Furia from Concerto No. 6 in D Major, (1709-70) after Domenico Scarlatti CELTIC LANDS: SCOTLAND AND IRELAND GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN L’Eccossoise from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D19 (1681–1767) NATHANIEL GOW Largo’s Fairy Dance: The Fairies Advancing and (1763–1831) Fairies Dance Cullen O’Neil, Solo Cello TELEMANN L’Irlandoise from Overture in D Minor, TVW55:d2 EASTERN EUROPE: POLAND, BOHEMIA, AND HUNGARY ARR. TELEMANN Danse de Polonie No. 4, TWV45 Polonaise from Concerto Polonois, TWV43:G7 Danse de Polonie No. 1, TWV45 La Hanaquoise, TWV55:D3 TRADITIONAL Three 18th-century Hanák folk tunes RUSSIA TELEMANN Les Moscovites from Overture in B-flat Major, TWV55:B5 Program continues 1 EUROPE DREAMS OF THE EAST: THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE TELEMANN Les Janissaries from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D17 Mezzetin en turc from Overture-Burlesque in B-flat Major, TWV55:B8 PERSIA AND CHINA JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU Air pour Borée from Les Indes galantes (1683–1764) Premier Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Seconde Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Entrée des Chinois -

A History of Electroacoustics: Hollywood 1956 – 1963 by Peter T

A History of Electroacoustics: Hollywood 1956 – 1963 By Peter T. Humphrey A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor James Q. Davies, Chair Professor Nicholas de Monchaux Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Nicholas Mathew Spring 2021 Abstract A History of Electroacoustics: Hollywood 1956 – 1963 by Peter T. Humphrey Doctor of Philosophy in Music and the Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor James Q. Davies, Chair This dissertation argues that a cinematic approach to music recording developed during the 1950s, modeling the recording process of movie producers in post-production studios. This approach to recorded sound constructed an imaginary listener consisting of a blank perceptual space, whose sonic-auditory experience could be controlled through electroacoustic devices. This history provides an audiovisual genealogy for electroacoustic sound that challenges histories of recording that have privileged Thomas Edison’s 1877 phonograph and the recording industry it generated. It is elucidated through a consideration of the use of electroacoustic technologies for music that centered in Hollywood and drew upon sound recording practices from the movie industry. This consideration is undertaken through research in three technologies that underwent significant development in the 1950s: the recording studio, the mixing board, and the synthesizer. The 1956 Capitol Records Studio in Hollywood was the first purpose-built recording studio to be modelled on sound stages from the neighboring film lots. The mixing board was the paradigmatic tool of the recording studio, a central interface from which to direct and shape sound. -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

Access to Communications Technology

A Access to Communications Technology ABSTRACT digital divide: the Pew Research Center reported in 2019 that 42 percent of African American adults and Early proponents of digital communications tech- 43 percent of Hispanic adults did not have a desk- nology believed that it would be a powerful tool for top or laptop computer at home, compared to only disseminating knowledge and advancing civilization. 18 percent of Caucasian adults. Individuals without While there is little dispute that the Internet has home computers must instead use smartphones or changed society radically in a relatively short period public facilities such as libraries (which restrict how of time, there are many still unable to take advantage long a patron can remain online), which severely lim- of the benefits it confers because of a lack of access. its their ability to fill out job applications and com- Whether the lack is due to economic, geographic, or plete homework effectively. demographic factors, this “digital divide” has serious There is also a marked divide between digital societal repercussions, particularly as most aspects access in highly developed nations and that which of life in the twenty-first century, including banking, is available in other parts of the world. Globally, the health care, and education, are increasingly con- International Telecommunication Union (ITU), a ducted online. specialized agency within the United Nations that deals with information and communication tech- DIGITAL DIVIDE nologies (ICTs), estimates that as many as 3 billion people living in developing countries may still be In its simplest terms, the digital divide refers to the gap unconnected by 2023. -

Les Talens Lyriques the Ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, Which Takes Its

Les Talens Lyriques The ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, which takes its name from the subtitle of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Les Fêtes d’Hébé (1739), was formed in 1991 by the harpsichordist and conductor Christophe Rousset. Championing a broad vocal and instrumental repertoire, ranging from early Baroque to the beginnings of Romanticism, the musicians of Les Talens Lyriques aim to throw light on the great masterpieces of musical history, while providing perspective by presenting rarer or little known works that are important as missing links in the European musical heritage. This musicological and editorial work, which contributes to its renown, is a priority for the ensemble. Les Talens Lyriques perform to date works by Monteverdi (L'Incoronazione di Poppea, Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, L’Orfeo), Cavalli (La Didone, La Calisto), Landi (La Morte d'Orfeo), Handel (Scipione, Riccardo Primo, Rinaldo, Admeto, Giulio Cesare, Serse, Arianna in Creta, Tamerlano, Ariodante, Semele, Alcina), Lully (Persée, Roland, Bellérophon, Phaéton, Amadis, Armide, Alceste), Desmarest (Vénus et Adonis), Mondonville (Les Fêtes de Paphos), Cimarosa (Il Mercato di Malmantile, Il Matrimonio segreto), Traetta (Antigona, Ippolito ed Aricia), Jommelli (Armida abbandonata), Martin y Soler (La Capricciosa corretta, Il Tutore burlato), Mozart (Mitridate, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Così fan tutte, Die Zauberflöte), Salieri (La Grotta di Trofonio, Les Danaïdes, Les Horaces, Tarare), Rameau (Zoroastre, Castor et Pollux, Les Indes galantes, Platée, Pygmalion), Gluck -

Rameau's Imaginary Monsters: Knowledge, Theory, And

Rameau's Imaginary Monsters: Knowledge, Theory, and Chromaticism in Hippolyte et Aricie Author(s): Charles Dill Source: Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 55, No. 3 (Winter 2002), pp. 433- 476 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the American Musicological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jams.2002.55.3.433 . Accessed: 04/09/2014 11:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and American Musicological Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the American Musicological Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.104.46.206 on Thu, 4 Sep 2014 11:26:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Rameau's Imaginary Monsters: Knowledge, Theory, and Chromaticism in Hippolyte etAricie CHARLES DILL dialectic existed at the heart of Enlightenment thought, a tension that sutured instrumentalreason into place by offering the image of its irra- JL A1tional other. Embedded within the rationalorder of encyclopedicen- terpriseslay the threat posed by superstition,both religious and unlettered; contained and controlled by the solid foundations of social contractswas the disturbing image of chaos, evoked musically by Jean-FeryRebel and Franz Joseph Haydn, and among the nobly formed figures of humankind and nature there lurked deformity and aberration,there lurked the monster. -

Evening Program

2021 18:30 & 20:30 24.04.Grand Auditorium Samedi / Samstag / Saturday Voyage dans le temps «Rameau: une symphonie imaginaire» Les Musiciens du Louvre Marc Minkowski direction Ce concert sera filmé et disponible ultérieurement sur la chaîne YouTube ainsi que la page Facebook de la Philharmonie Luxembourg. Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) Zaïs: Ouverture (1748) Castor et Pollux: Scène funèbre (1737) Les Fêtes d’Hébé: Air tendre (1739) Dardanus: Tambourins (1739) Le Temple de la Gloire: Air tendre pour les Muses (1745) Les Boréades: Contredanse (1763) La Naissance d’Osiris: Air gracieux (1754) Les Boréades: Gavottes pour les Heures et les Zéphirs (1763) Platée: Orage (1745) Les Boréades: Prélude (1763) Concert N° 6 en sextuor: 1. La Poule (1768) Les Fêtes d’Hébé: Musette & Tambourin (1739) Hippolyte et Aricie: Ritournelle (1733) Naïs: Rigaudons (1749) Les Indes galantes: Danse des Sauvages (1735) Les Boréades: Entrée de Polymnie (1763) Les Indes galantes: Chaconne (1735) 60’ Les Boréades, œuvre posthume de Jean-Philippe Rameau, 1764, Origine: Manuscrit Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Rés.Vmb Ms4. Copyright 1982, 1998 et 2001 Alain Villain, Éditions Stil, Paris D’Distanzknuddler Martin Fengel Une symphonie du cœur Sylvie Bouissou Immense génie déconnecté des conventions sociales, souvent en décalage avec son époque, d’abord trop italien pour les lullistes, puis plus assez pour les adeptes de l’opéra-comique, trop « savant » pour avoir du cœur, Rameau a subi les goûts versatiles, les amours et les trahisons d’une société inconstante. Sans doute faut-il voir dans la remarque de d’Alembert, coauteur avec Diderot de l’En- cyclopédie, le commentaire le plus éclairé sur sa musique : « Il a osé tout ce qu’il a pu, et non tout ce qu’il aurait voulu oser […] il nous a donné non pas la meilleure musique dont il était capable, mais la meil- leure que nous puissions recevoir » (Mélanges de littérature, d’histoire et de philosophie, t.