Rameau's Imaginary Monsters: Knowledge, Theory, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wednesday Playlist

September 25, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “Art and life are not two separate things.” — Gustav Mahler Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Sibelius The Swan of Tuonela Boston Symphony/Davis Philips 446 160 028944616026 Awake! 00:11 Buy Now! Elgar The Sanguine Fan, Op. 81 London Philharmonic/Boult EMI 63133 077776313320 00:30 Buy Now! Mozart Piano Quartet No. 2 in E flat, K. 493 Bronfman/Zukerman/Marks/Forsyth RCA Red Seal 88697160442 886971604429 01:00 Buy Now! Gershwin Lullaby for Strings Cincinnati Pops/Kunzel Telarc 80503 089408050329 01:10 Buy Now! Bach English Suite No. 4 in F, BWV 809 Glenn Gould Sony 52606 n/a 01:28 Buy Now! Strauss, R. Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme Suite Chicago Symphony/Reiner RCA 5721 07863557212 01:59 Buy Now! Mozart Overture ~ The Magic Flute, K. 620 Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields/Marriner EMI 47014 077774701426 Virgin Classics 02:07 Buy Now! Rameau Fourth Concert (for harpsichord and strings) Trio Sonnerie 90749 07567907492 Digital 02:19 Buy Now! Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, Op. 73 "Emperor" Arrau/Dresden State Orchestra/Davis Philips 416 215 028941621528 03:01 Buy Now! Mascagni Intermezzo ~ Cavalleria rusticana Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Sony 48260 07464482602 03:05 Buy Now! Shostakovich Cello Concerto No. 1 in E flat, Op. 107 Kanneh-Mason/CBSO/Grazinyte-Tyla Decca 483 2948 028948329489 03:38 Buy Now! Telemann Paris Quartet No. 10 Kuijken Bros/Leonhardt Sony 63115 074646311523 03:59 Buy Now! Chopin Scherzo No. -

RAMEAU LES BORÉADES Václav Luks MENU

RAMEAU LES BORÉADES Václav Luks MENU Tracklist Distribution L'œuvre Compositeur Artistes Synopsis Textes chantés L'Opéra Royal 1 MENU LES BORÉADES VOLUME 1 69'21 1 Ouverture 2'28 2 Menuet 0'44 3 Allegro 1'32 ACTE I 4 Scène 1 - Alphise et Sémire 3'19 Récits en duo et Airs d'Alphise «Suivez la chasse» Deborah Cachet, Caroline Weynants 5 Scène 2 - Borilée et les Précédents 0'29 Air et Récit de Borilée «La chasse à mes regards» Tomáš Šelc 6 Scène 3 - Calisis et les Précédents 2'08 Récit et Air de Calisis «À descendre en ces lieux» Deborah Cachet, Benedikt Kristjánsson 7 Scène 4 - Troupe travestie en Plaisirs et Grâces 0'35 Air de Calisis «Cette troupe aimable» Caroline Weynants, Benedikt Kristjánsson 8 Air gracieux (Ballet) 1'51 9 Air de Sémire «Si l'hymen a des chaines» – Caroline Weynants 0'40 10 Première Gavotte gracieuse 0'32 11 Deuxième Gavotte (Ballet) 0'46 12 Première Gavotte da capo (Ballet) 0'18 2 13 Air de Calisis «C'est dans cet aimable séjour» – Benedikt Kristjánsson 0'46 14 Rondeau vif (Ballet) – Caroline Weynants 2'23 15 Gavotte vive (Ballet) 0'51 16 Deuxième Gavotte (Ballet) 0'53 17 Ariette pour Alphise ou la Confidente (Sémire) «Un horizon serein» 7'37 Deborah Cachet ou Caroline Weynants 18 Contredanse en Rondeau (Ballet) 1'57 19 L'Ouverture pour Entracte ACTE II 20 Scène 1 - Abaris 2'25 Air d'Abaris «Charmes trop dangereux» Mathias Vidal 21 Scène 2 - Adamas et Abaris 0'31 Récit d'Adamas «J'aperçois ce mortel» Benoît Arnould 22 Air d'Adamas «Lorsque la lumière féconde» – Benoît Arnould 1'08 23 Récit d'Abaris et Adamas «Quelle -

Rameau Et L'opéra Comique

2020 HIPPOLYTE ET ARICIE HIPPOLYTE ET ARICIEJEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU 11, 14, 15, 18, 21, 22 NOVEMBRE 2020 1 Soutenu par Soutenu par AVEC L'AIMABLE AVEC LE SOUTIEN DE PARTENARIAT MÉDIA Madame Aline Foriel-Destezet, PARTICIPATION DE Grande Donatrice de l’Opéra Comique Spectacle capté les 15 et 18 novembre et diffusé ultérieurement. 2 HIPPOLYTETragédie lyrique en cinq actes de Jean-Philippe ET ARICIE Rameau. Livret de l’abbéer Pellegrin Créée à l’Académie royale de musique (Opéra) le 1 octobre 1733. Version de 1757 (sans prologue) avec restauration d’éléments des versions antérieures (1733 et 1742). Raphaël Pichon Direction musicale - Jeanne Candel Mise en scène -Lionel Gonzalez Dramaturgie et direction d’acteurs - Lisa Navarro DécorsPauline - Kieffer Costumes -César Godefroy Lumières - Yannick Bosc Collaboration aux mouvements - Ronan Khalil * Chef de chant - Valérie Nègre Assistante mise en scène -Margaux Nessi Assistante décorsNathalie - Saulnier Assistante costumes - Reinoud van Mechelen Hippolyte - Elsa Benoit SylvieAricie Brunet-Grupposo - Phèdre - Stéphane Degout Opéra Comique Thésée - Nahuel Di Pierro Production Opéra Royal – Château de Versailles Spectacles Neptune, Pluton -Eugénie Lefebvre Coproduction Diane - Lea Desandre Prêtresse de Diane, Chasseresse, Matelote, BergèreSéraphine - Cotrez © Édition Nicolas Sceaux 2007-2020 Œnone - Edwin Fardini Pygmalion. Tous droits réservés Constantin Goubet* re Tisiphone - Martial Pauliat* e 1 Parque - 3h entracte compris Virgile Ancely * 2 Parque,e Arcas - Durée estimée : 3 ParqueGuillaume - Gutierrez* Mercure - * MembresYves-Noël de Pygmalion Genod Iliana Belkhadra Introduction au spectacle Chantez Hippolyte Prologue - Leena Zinsou Bode-Smith (11, 15, 18 et 22 novembre) / et Aricie et Maîtrise Populaire de(14 l’Opéra et 21 novembre) Comique sont temporairement suspendues en raison de la des conditions sanitaires. -

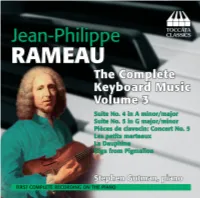

Toccata Classics TOCC0052 Notes

RAMEAU ON THE PIANO, VOLUME THREE 1 by Graham Sadler The two suites recorded on this disc are from the Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin of 1729 or 1730, Rameau’s final collection of solo keyboard music.2 Like those of his Pièces de clavessin (1724), they are contrasted both in tonality and character. The Suite in A minor and major is dominated by dances and includes only three character pieces, whereas the Suite in G major and minor consists almost exclusively of pieces with character titles. In its make-up if not its style, the latter thus follows the example of François Couperin, whose first three books of pièces de clavecin (1713, 1717 and 1722) had established the vogue for descriptive pieces. In that sense, Rameau may be regarded as somewhat conservative in devoting half of his two mature solo collections to suites of the more traditional type. Suite No. 4 in A minor and major Conservative they may be, but the dance movements of the Nouvelles suites are among the most highly P developed in the repertory, the first two particularly so. The Allemande 1 unfolds with an effortless grace, its unerring sense of direction reinforced by the many sequential passages. At the end of both sections, the duple semiquaver motion gives way unexpectedly to triplet motion, providing a memorable ‘rhyme’ to the two parts of the movement. The Courante 2, more than twice as long as its predecessors in Rameau’s output, displays a technical sophistication without parallel in the clavecin repertory. Three themes interlock in mainly three- part counterpoint – a bold motif in rising fourths, and two accompanying figures in continuous quavers, the one in sinuous stepwise movement, the other comprising cascading arpeggios. -

Le Monde Galant

The Juilliard School presents Le Monde Galant Juilliard415 Nicholas McGegan, Director Recorded on May 1, 2021 | Peter Jay Sharp Theater FRANCE ANDRÉ CAMPRA Ouverture from L’Europe Galante (1660–1744) SOUTHERN EUROPE: ITALY AND SPAIN JEAN-MARIE LECLAIR Forlane from Scylla et Glaucus (1697–1764) Sicilienne from Scylla et Glaucus CHRISTOPH WILLIBALD GLUCK Menuet from Don Juan (1714–87) MICHEL RICHARD DE LALANDE Chaconne légère des Maures from Les Folies (1657–1726) de Cardenio CHARLES AVISON Con Furia from Concerto No. 6 in D Major, (1709-70) after Domenico Scarlatti CELTIC LANDS: SCOTLAND AND IRELAND GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN L’Eccossoise from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D19 (1681–1767) NATHANIEL GOW Largo’s Fairy Dance: The Fairies Advancing and (1763–1831) Fairies Dance Cullen O’Neil, Solo Cello TELEMANN L’Irlandoise from Overture in D Minor, TVW55:d2 EASTERN EUROPE: POLAND, BOHEMIA, AND HUNGARY ARR. TELEMANN Danse de Polonie No. 4, TWV45 Polonaise from Concerto Polonois, TWV43:G7 Danse de Polonie No. 1, TWV45 La Hanaquoise, TWV55:D3 TRADITIONAL Three 18th-century Hanák folk tunes RUSSIA TELEMANN Les Moscovites from Overture in B-flat Major, TWV55:B5 Program continues 1 EUROPE DREAMS OF THE EAST: THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE TELEMANN Les Janissaries from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D17 Mezzetin en turc from Overture-Burlesque in B-flat Major, TWV55:B8 PERSIA AND CHINA JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU Air pour Borée from Les Indes galantes (1683–1764) Premier Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Seconde Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Entrée des Chinois -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1954-1956

contltictA me «L$o4tim ^ymfmtmu &^cAe4t^a RCA Victor recreates all the eloquence of his interpretations in these brilliant "New Orthophonic ' High Fidelity recordings **Berlioz:The Damnation of Faust (complete)—Suzanne Danco, Soprano; David Poleri, Tenor; Martial Singher, Baritone **Berlioz: Romeo and Juliet (complete)—Margaret Roggero, Contralto; Leslie Chabay, Tenor; Yi-Kwei Sze, Bass **Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2, in B Flat, op. 83—Artur Rubinstein, Piano *Beethoven: Symphony No. 7, in A, op. 92 **Chopin: Piano Concerto No. 2, in F Minor. **Saint-Saens: Piano Concerto No. 4, in C Minor—Alexander Brailowsky, Piano. **"New Orthophonic' High Fidelity. *High Fidelity. rcaVictor D I D MUSIC ill ^i1 s i ? » "• I *> ". :, Pv ^H—JL i i ~.~z~ BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director Berkshire Festival, Season 1955 (EIGHTEENTH SEASON) TANGLEWOOD, LENOX, MASSACHUSETTS FIRST WEEK Concert Bulletin, with historical and descriptive notes by John 1\. Burk copyright. l955, by boston symphony orchestra, inc. Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Henry B. Cabot, President Jacob J. Kaplan, Vice-President Richabd C. Paine, Treasurer Talcott M. Banks, Jr. \lvan I. Fuller C. D. Jackson Charles H. Stockton John Nicholas Brown Francis W. Hatch Michael T. Kelleher Ldward A. Taft Theodore P. Ferris Harold D. Hodgkinson Palfrey Perkins Raymond S. Wilkins Oliver Wolcott Trustees Emeritus Philip B. \lleiv M. A. DeWolfe Howe N. Penrose Hallowell Lewis Perry Tanglewood Advisory Committee \i.\n J. Blai Henry W. Dwight F. Anthony Hanlon George E. Mole Lenges Bi m George W. Edman Lawrence K. Miller Whitney S. Stoddard Jesse L. Thomason Bobert K. Wheeler H. -

Les Talens Lyriques the Ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, Which Takes Its

Les Talens Lyriques The ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, which takes its name from the subtitle of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Les Fêtes d’Hébé (1739), was formed in 1991 by the harpsichordist and conductor Christophe Rousset. Championing a broad vocal and instrumental repertoire, ranging from early Baroque to the beginnings of Romanticism, the musicians of Les Talens Lyriques aim to throw light on the great masterpieces of musical history, while providing perspective by presenting rarer or little known works that are important as missing links in the European musical heritage. This musicological and editorial work, which contributes to its renown, is a priority for the ensemble. Les Talens Lyriques perform to date works by Monteverdi (L'Incoronazione di Poppea, Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, L’Orfeo), Cavalli (La Didone, La Calisto), Landi (La Morte d'Orfeo), Handel (Scipione, Riccardo Primo, Rinaldo, Admeto, Giulio Cesare, Serse, Arianna in Creta, Tamerlano, Ariodante, Semele, Alcina), Lully (Persée, Roland, Bellérophon, Phaéton, Amadis, Armide, Alceste), Desmarest (Vénus et Adonis), Mondonville (Les Fêtes de Paphos), Cimarosa (Il Mercato di Malmantile, Il Matrimonio segreto), Traetta (Antigona, Ippolito ed Aricia), Jommelli (Armida abbandonata), Martin y Soler (La Capricciosa corretta, Il Tutore burlato), Mozart (Mitridate, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Così fan tutte, Die Zauberflöte), Salieri (La Grotta di Trofonio, Les Danaïdes, Les Horaces, Tarare), Rameau (Zoroastre, Castor et Pollux, Les Indes galantes, Platée, Pygmalion), Gluck -

Dardanus De Jean-Philippe Rameau Direction Musicale Emmanuelle Haïm Mise En Scène Claude Buchvald Chorégraphie Daniel Larrieu Chœur Et Orchestre Du Concert D’Astr Ée

Dossier pédagogique Opéra / Nouvelle production DARDANUS DE JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU DIRECTION MUSICALE EMMANUELLE HAÏM MISE EN SCÈNE CLAUDE BUCHVALD CHORÉGRAPHIE DANIEL LARRIEU CHŒUR ET ORCHESTRE DU CONCERT D’ASTR ÉE Du 16 au 24 octobre 2009 Contacts Service des relations avec les publics [email protected] Dossier réalisé avec la collaboration de Sébastien Bouvier, enseignant missionné à l’Opéra de Lille Septembre 2009 Sommaire Préparer votre venue à l’Opéra 3 DARDANUS Résumé 4 Synopsis 5 La musique baroque 6 La tragédie lyrique ou « tragédie en musique » 7 Les instruments baroques 10 La danse dans l’opéra baroque 12 Guide d’écoute 14 Vocabulaire 21 Références 22 DARDANUS À L’OPÉRA DE LILLE Distribution 23 Notes d’intention de mise en scène 24 Repères biographiques 25 POUR ALLER PLUS LOIN La Voix à l’opéra 27 Qui fait quoi à l’opéra ? 29 L’Opéra de Lille, un lieu, une histoire 30 ANNEXES Les instruments de l’orchestre 34 Annexe : frise chronologique sur Rameau et son époque 35 2 Préparer votre venue Ce dossier vous aidera à préparer votre venue avec les élèves. L’équipe de l’Opéra de Lille est à votre disposition pour toute information complémentaire et pour vous aider dans votre approche pédagogique. Si le temps vous manque, nous vous conseillons, prioritairement, de : - lire la fiche résumé et le synopsis détaillé - faire une écoute des extraits représentatifs de l’opéra (guide d’écoute) Recommandations Le spectacle débute à l’heure précise, 20h ou 16h le dimanche. Il est donc impératif d’arriver au moins 30 minutes à l’avance, les portes sont fermées dès le début du spectacle. -

Redalyc.Recueil D'anecdotes Musicales Du Xviiie Siècle

Çedille. Revista de Estudios Franceses E-ISSN: 1699-4949 [email protected] Asociación de Francesistas de la Universidad Española España Abramovici, Jean Christophe; Sanz, Teo Recueil d'anecdotes musicales du XVIIIe siècle Çedille. Revista de Estudios Franceses, núm. 3, abril, 2007, pp. 19-33 Asociación de Francesistas de la Universidad Española Tenerife, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=80800304 Comment citer Numéro complet Système d'Information Scientifique Plus d'informations de cet article Réseau de revues scientifiques de l'Amérique latine, les Caraïbes, l'Espagne et le Portugal Site Web du journal dans redalyc.org Projet académique sans but lucratif, développé sous l'initiative pour l'accès ouverte ISSN: 1699-4949 nº 3, abril de 2007 Monografía La anécdota en el siglo XVIII Recueil d’anecdotes musicales du XVIIIe siècle* Jean-Christophe Abramovici Université de Valenciennes [email protected] Teo Sanz Universidad de Burgos [email protected] 1. Sur la musique, les ballets, les concerts et les spectacles musicaux en général: En 1722, le régent et ses compagnons de débauches célébraient des orgies qu’ils appelaient fêtes d’Adam. Laissons parler le duc de Richelieu, qui sans doute y assistait (...). «D’autres fois, on choisissait les plus beaux jeunes gens de l’un et de l’autre sexe qui dansaient à l’Opéra, pour répéter des ballets que le ton aisé de la société, pendant la régence, avait rendus si lascifs, et que ces gens exécutaient dans cet état primitif où étaient les hommes avant qu’ils connussent les voiles et les vêtements. Ces orgies, que le régent, Dubois et ses roués appelaient fêtes d’Adam, furent répétées une douzaine de fois; car le prince parut s’en dégoûter» (Dulaure, III, 493-494). -

Evening Program

2021 18:30 & 20:30 24.04.Grand Auditorium Samedi / Samstag / Saturday Voyage dans le temps «Rameau: une symphonie imaginaire» Les Musiciens du Louvre Marc Minkowski direction Ce concert sera filmé et disponible ultérieurement sur la chaîne YouTube ainsi que la page Facebook de la Philharmonie Luxembourg. Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) Zaïs: Ouverture (1748) Castor et Pollux: Scène funèbre (1737) Les Fêtes d’Hébé: Air tendre (1739) Dardanus: Tambourins (1739) Le Temple de la Gloire: Air tendre pour les Muses (1745) Les Boréades: Contredanse (1763) La Naissance d’Osiris: Air gracieux (1754) Les Boréades: Gavottes pour les Heures et les Zéphirs (1763) Platée: Orage (1745) Les Boréades: Prélude (1763) Concert N° 6 en sextuor: 1. La Poule (1768) Les Fêtes d’Hébé: Musette & Tambourin (1739) Hippolyte et Aricie: Ritournelle (1733) Naïs: Rigaudons (1749) Les Indes galantes: Danse des Sauvages (1735) Les Boréades: Entrée de Polymnie (1763) Les Indes galantes: Chaconne (1735) 60’ Les Boréades, œuvre posthume de Jean-Philippe Rameau, 1764, Origine: Manuscrit Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Rés.Vmb Ms4. Copyright 1982, 1998 et 2001 Alain Villain, Éditions Stil, Paris D’Distanzknuddler Martin Fengel Une symphonie du cœur Sylvie Bouissou Immense génie déconnecté des conventions sociales, souvent en décalage avec son époque, d’abord trop italien pour les lullistes, puis plus assez pour les adeptes de l’opéra-comique, trop « savant » pour avoir du cœur, Rameau a subi les goûts versatiles, les amours et les trahisons d’une société inconstante. Sans doute faut-il voir dans la remarque de d’Alembert, coauteur avec Diderot de l’En- cyclopédie, le commentaire le plus éclairé sur sa musique : « Il a osé tout ce qu’il a pu, et non tout ce qu’il aurait voulu oser […] il nous a donné non pas la meilleure musique dont il était capable, mais la meil- leure que nous puissions recevoir » (Mélanges de littérature, d’histoire et de philosophie, t. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02156-3 - Dramatic Expression in Rameau’s Tragédie en Musique: Between Tradition and Enlightenment Cynthia Verba Index More information Index accompanied recitative chromatics, 27, 38, 62, 68, 69, 72, 75–76, 78, as tonal anchors, 32 80, 86, 88–89, 92–93, 140, 147, 148, in Dardanus, 131, 194–196, 203 169, 175, 176, 179, 185, 186, 193, 196, in Hippolyte et Aricie, 66, 67, 72, 79–80, 90, 210, 244, 249, 286, 291 115 classical models of tragedy, 85, 181 (see also in Les Bor´eades, 218 Aristotelian poetics) in Zoroastre, 292–295 Cohen, David E., 30–31 airs contrary duos, 67–68, 69–71, as tonal anchors, 32, 34, 36 251–253 in Castor et Pollux, 124 Cowart, Georgia, 8–10 in Dardanus, 129, 196–199, 291–292 in Hippolyte et Aricie, 51–53, 54–62, 65, 74, da capo arias, 4, 144, 163, 183–188, 200–203, 79, 80–84, 86, 90–93 210, 212, 247–249 in Les Bor´eades, 169, 171–172, 175, 178–179, terminology, x 214–216, 217–218 D’Alembert,JeanleRond,2–3 in Lully’s operas, 7, 17–18 deities in Zoroastre, 134, 137, 140–141, 147, interventions, imposed by deities, 84, 148–149, 152, 153–154, 155, 203–207 89–90, 116, 117, 118, 119, 123–124, terminology, x, 56 127, 129, 145, 161, 170, 175, 177, 179, Allanbrook, Wye Jamison, 32 301–302 ancien r´egime, 1, 7, 9–11, 14, 16, 108, 109, 314, invocations, addressing deities, 79–84, 316–317 85–89, 112, 115, 116, 125, 146–147, Anthony, James, 16, 20, 21 152–153, 174, 200–203 ariettes, 117, 124, 144, 163–167, 170, 172, 176, Diderot, Denis, 2, 3, 20, 31–32 302 Dill, Charles, 5, 8, 19, 21–22, 44, -

Castor & Pollux

JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU CASTOR & POLLUX (1754) Ainsworth | Sempey | De Negri | Margaine | Devieilhe | Immler PYGMALION RAPHAËL PICHON FRANZ LISZT JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU (1683-1764) CD 2 Scène 4. Pollux, Hébé, une Suivante d’Hébé, Plaisirs célestes (Suite d’Hébé) CASTOR & POLLUX (version de 1754) 1 | Entrée d’Hébé et de sa suite 1’24 Tragédie en musique en 5 actes 2 | Chœur des Plaisirs célestes : Pouvez-vous nous méconnaître ? 0’45 Livret Pierre-Joseph Bernard (Gentil-Bernard) 3 | Pollux : Tout l’éclat de l’Olympe 0’24 4 | Petit chœur des Suivantes d’Hébé : Qu’Hébé, de fleurs toujours nouvelles 0’55 5 | Sarabande pour Hébé et sa Suite 1’12 CD 1 6 | Une Suivante d’Hébé : Voici des dieux 1’52 7 | Pollux : Ah ! Sans le trouble où je me vois 0’28 8 | Air pour Hébé. Une Suivante d’Hébé : Que nos jeux 3’23 1 | Ouverture 4’24 9 | Première et deuxième gavottes pour Hébé 1’36 PREMIER ACTE 10 | Récit Quand je romps vos aimables chaînes 0’51 2 | Scène 1. Cléone, Phébé. Cléone : L’hymen couronne votre sœur 4’16 3 | Scène 2. Télaïre : Éclatez mes justes regrets 2’40 QUATRIÈME ACTE 4 | Scène 3. Télaïre, Castor. Castor : Ah ! Je mourrai content 3’12 Scène 1. Phébé, [Esprits, Puissances magiques] 5 | Scène 4. Pollux, Télaïre, Castor. Pollux : Non, demeure, Castor 1’50 11 | Phébé & Chœurs : Esprits soutiens de mon pouvoir 2’40 12 | Descente de Mercure 0’14 Scène 5. Pollux, Télaïre, Castor, Spartiates. Pollux : Ces apprêts m’étaient destinés 13 | Mercure, Phébé, Pollux. Mercure : 1’25 6 | Chœur de Spartiates : Chantons l’éclatante victoire 1’44 Scène 2.